By Rhys Jack on Nov 09, 2019 03:00 am

Sunday Telegraph, 10 November 2019

Described as the by-product of throwing Chuck Norris and Indiana Jones into a blender, this former Australian Army Major has been trekking across the infamous Kokoda trail for more than 28 years.

One of the most difficult things I’ve attempted in my life has to be trekking across the Kokoda Trail. Over 140 kilometres in length, and climbing up over 6,750 metres. It took nine days to hike from Owers’ Corner in the south of Papua New Guinea through the most humid jungles, across torrential rivers and over never-ending mountains that made me seriously question why the hell I was doing it. And finally, after being stretched to physical and mental limits, the trail winds down to the small village of Kokoda on the Northern plateau of the island where those who complete it can celebrate an incredible accomplishment.

People say you can’t explain what it’s like to trek Kokoda, and pictures just won’t do it justice. It’s something you just have to experience. It’s like travelling to the edge of existence and the only people who understand it are the ones standing next to you.

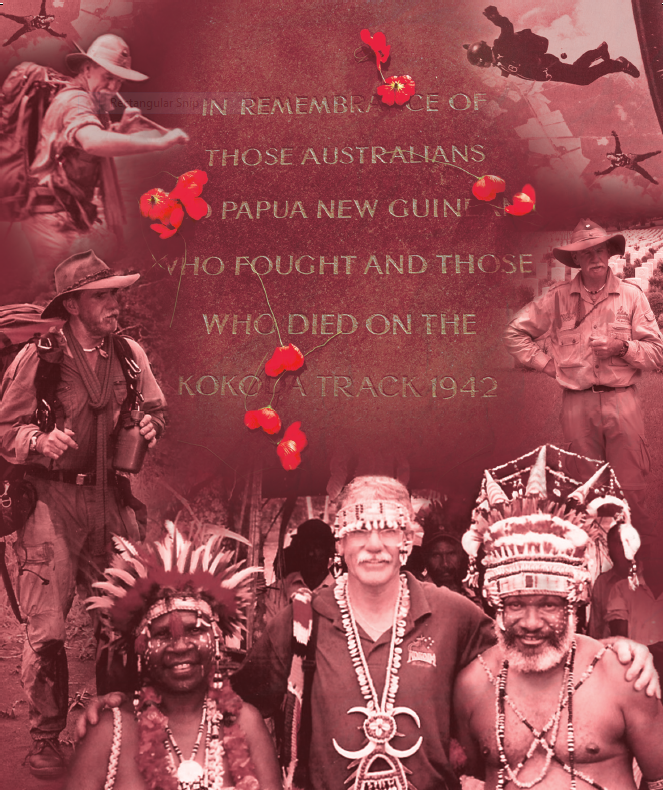

It’s a journey made all the more sobering because it’s also the setting of one of the most brutal military battles that occurred during World War II. It was there along that same track 77 years ago where thousands of Australian, American and local PNG men fought and died in a series of gruelling clashes against the advancing Japanese Army.

Today, many wartime artefacts remain virtually undisturbed in these forests. Unused mortars and grenades, discarded helmets and army boots, even the remains of a US P40 Kittyhawk fighter plane can all be found along the trail, you just need the right person to show you where.

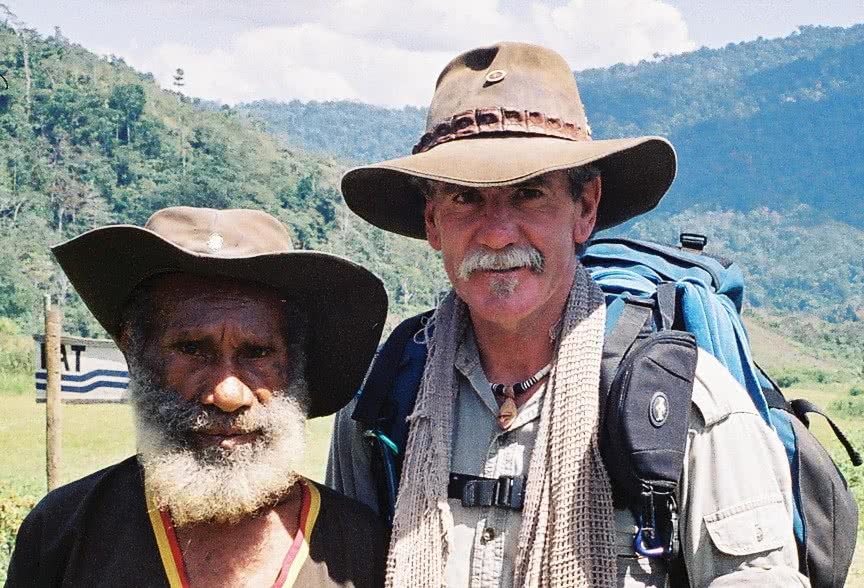

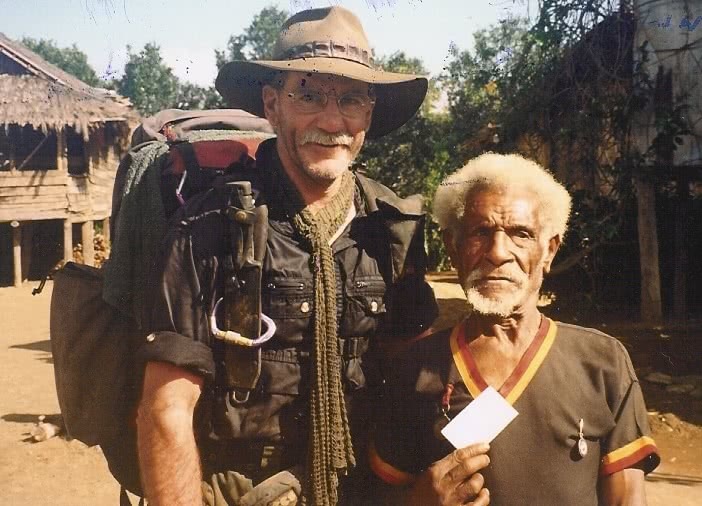

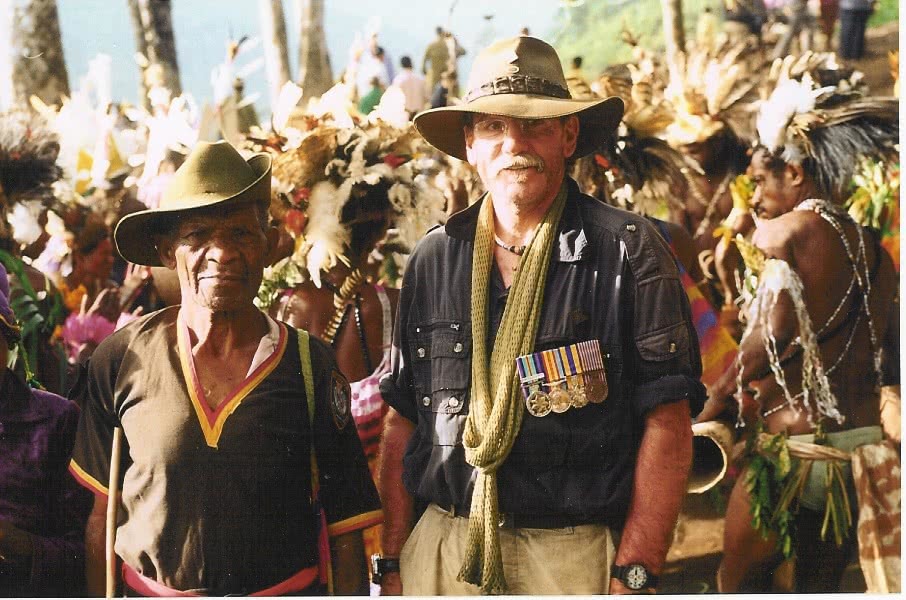

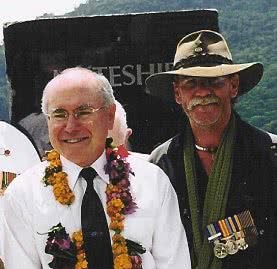

Charlie Lynn has dedicated much of his life to maintaining the legacy of this trail as a historic war site. And he was my guide when I trekked back in 2015. Approaching his 100th crossing of the trail Charlie shows no signs of stopping any time soon.

He’s a former Army Major, NSW State Politician and ultra-marathon runner. But for almost 30 years he’s been taking Australians across the trail after helping to uncover many of its historic sites and re-establish it as a memorial to the men and women who served there.

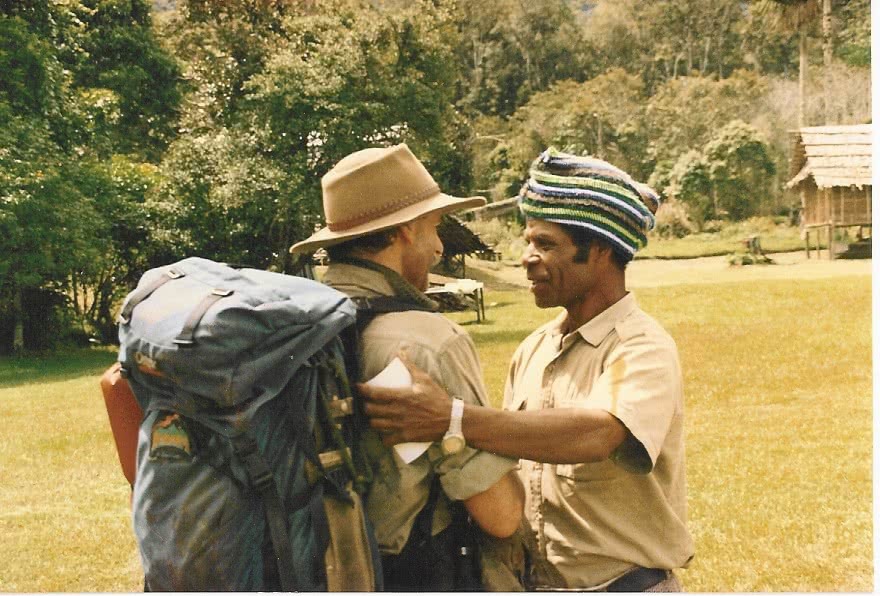

Sporting an Akubra hat at all times, a white handlebar moustache and covered in Khaki from head to toe, his hiking boots are immaculate and look as if he’s barely walked a mile.

He’s the type of person who when he shakes your hand, you know it. His laugh can be heard across any busy room and I’m certain the locals in PNG all hear him coming from next village along the trail.

He uses words like ‘digger’, ‘struth’ and ‘cooee cobber’ in passing conversation which makes you question when was last time you ever heard someone say any of those words.

He has a fierce passion for Kokoda, the challenge, and sharing its benefits with as many people as he can.

“Everything that is good about human nature can be found in that challenge (Kokoda). It’s about the ability of the human spirit to overcome adversity, the ability to help out your mates when they are struggling, because we will all struggle. It’s about keeping physically fit, about having a goal and it’s about helping others. But most importantly It’s about respecting the values our diggers fought for in 1942.”

As the eldest of eight children, Charlie became accustomed to challenging circumstances from a young age.

“I spent the first seven years of my life in and out of hospital with everything you could imagine, I had my tonsils out twice, I had appendicitis, I had a cyst the size of an orange on my lung that had to be removed, and on top of all of that I was a chronic asthmatic. The Doctors told me I’d never work outside, and that I’d have to work in an office all my life.”

In 1965 Charlie was conscripted into the National Service and was soon on his way to Vietnam. It was a moment that would impact his life forever and inspire a deeply held respect for his country and the defence force.

“I cannot remember a day in 21 years where I didn’t just wake up wanting to go to work. I can’t think of a day where I didn’t put on my uniform and feel proud to be a soldier.”

“I also felt a great responsibility in wearing the uniform, in remembering the legacy of the ANZAC’s and the legacy of my father (who served in PNG during WWII), I very much wanted them to feel proud of me.”

After serving in Vietnam Charlie decided he wanted to join the Army full time and become a Commissioned Officer. But after spending time at the Officer Cadet School in Portsea he was told he wouldn’t graduate as his leadership abilities were unsatisfactory.

That was right up until the final training exercises for the graduating class.

“They sent me up to the Victorian Alps in a land rover to support the final bush exercise for the graduation class – it was mid-winter and I recall looking at the dark clouds as we got closer and realised it was going to be wet and cold. The weather was about as bad as it gets – wet, mud, freezing and dark. After about a week the cadets started dropping like flies and all I can remember is working my arse off to help them. It quickly turned into an emergency and the exercise was cancelled.”

“We returned home the next morning where I was called before the Commandant and they told me they had changed their mind and that I was going to graduate and become an officer.”

In the notes of Charlie’s leadership assessment from the time, Major Terry Holland wrote.

“Lynn carried on his tasks displaying excellent leadership qualities. He was by far the best-performed cadet.”

From that moment on Charlie threw himself into everything he could in the army, travelling to Singapore and Malaysia throughout his career as well as in the US as an instructor of Airborne Logistics. He worked his way up to the rank of Major before retiring in 1985.

When he left the Army Charlie developed a passion for ultra-marathon running and became race director for the Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Ultramarathon. It was in this role where he was invited by a group of Papua New Guinea locals to help organise an ultramarathon race along the Kokoda Trail.

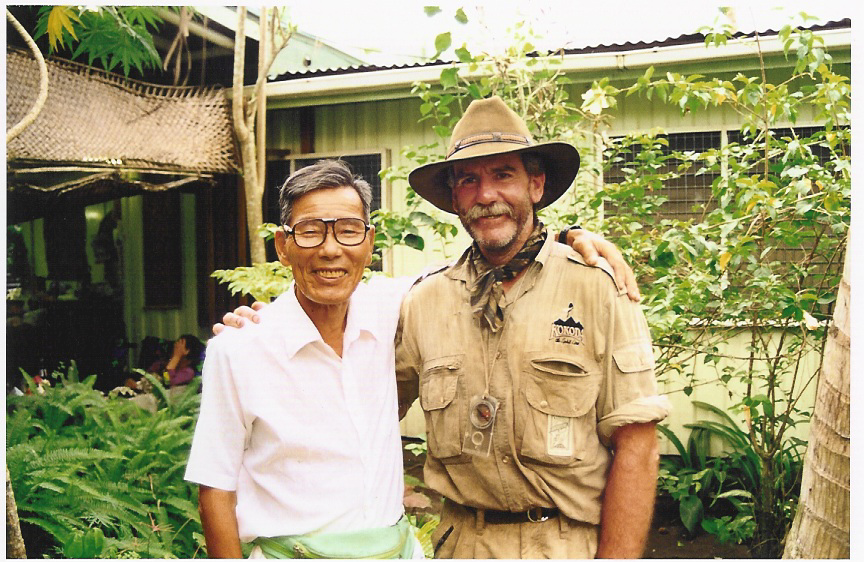

Charlie travelled to PNG for the first time to see the trail and find it’s all but forgotten battle sites.

“I was bitterly disappointed because there was not a single signpost, monument or memorial along the entire track apart from a few plaques placed by regimental associations and a small plinth erected by a Japanese soldier.”

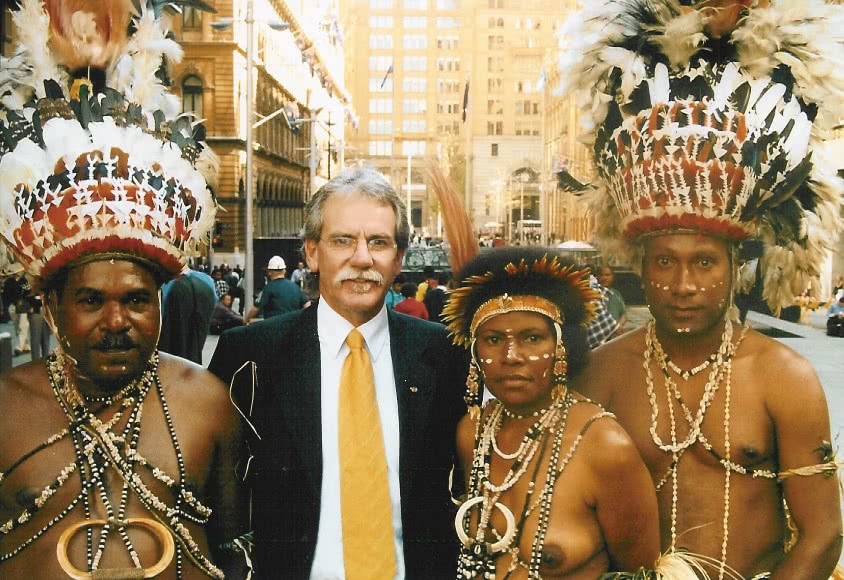

So, when he returned to Australia, Charlie started his trekking company Adventure Kokoda and has been working to establish the trail as a tourist destination in Papua New Guinea ever since.

Today, the philanthropic arm of Adventure Kokoda— Network Kokoda, contributes directly to the local communities who live along the path. Providing education and leadership programs to locals and more recently funding the establishment of a Tuberculosis Ward following a pandemic outbreak in the country.

I remember while I was trekking back in 2015, and stopping for a water break and catch my breath, it was only a matter of time before out of the jungle Charlie would appear — always at the very back of the group.

I asked him why it is he always treks at the back.

“If people are going to need help, it’s going to be at the back, that’s where it’s needed most.” He says. “And at 74 it’s the fastest I can go.”

He has seen a lot of trekkers from all walks of life struggle from that particular vantage point, and you sense over time he has developed an understanding of what a person or group needs to hear most.

Which is probably why he has memorised dozens of letters and stories written in various journals and books about what happened to the people who were involved during the battles along the trail.

He recites each story in the location where the events they describe occurred. And continues this process along the length of the trail. Recounting the experiences of young Australian soldiers who fought and died on the same ground you are standing on.

“50 years after the diggers returned from these battles, the veterans started to open up about their experiences, and they started putting these amazing books together. And these books weren’t about guns blowing this person away or aircraft destroying that group. They were about that person’s emotional journeys, and that’s what people connect to the most.”

“I want people to be able to come back from Kokoda and look in the mirror and say, I’m the best thing I’ve got going for me, and to go and out make a difference in life.”

It’s hard not to be inspired talking to Charlie, he has lived an incredible life in many ways and is relentlessly looking for new opportunities to make a difference. He has made a life out of challenging himself and others to push beyond what they previously thought possible and uncovering something unbelievable in the process.

Recent Articles:

Profile: Rigan Machado – The Martial Arts Life

What makes a great legacy?

20 Lessons In Life I Wish I’d Known Ten Years Ago.

The Value Of Competing: Why Putting Yourself In The Arena Is Necessary For Life.

Three Solutions To Defeat Worry.

This man is amazing. I had the privilege of doing the trek along with my sister and brother in law. It was bloody tough but he made you feel you wanted to do it again. We haven’t !!. His knowledge and passion is second to none. There are other cheaper tour operators out their but Charlie’s is the best. Charlie is one of Australia’s treasures.