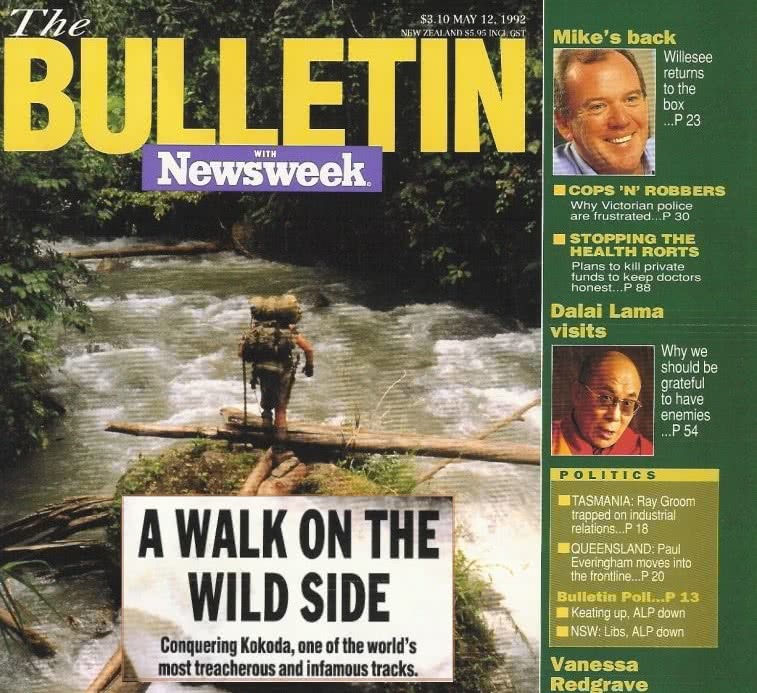

Geo Magazine: May – June 1997

OVERCOME by emotion Dr John de Courcy halts mid-sentence. Lying almost flat, his head propped against the thatched wall of a smoke-filled hut in the remote ranges of Papua New Guinea, he tries to describe those who have influenced his life. After a short pause, he continues without inhibition and his audience listens with empathy. It’s the kind of exchange that only a collective experience – bordering on near hell – is likely to deliver.

“Growing up during the depression, my father had a very difficult childhood, though he never admitted it,” said the 36-year-old paediatrician, referred to by his 22 fellow trekkers as Dr John reveals a profound admiration for his father and the sacrifices made in order to give his children the best possible chance in life.

After the first half of a 11-day trudge along the notorious Kokoda Trail, such honest exchanges are the result of leadership training Charlie Lynn style. A former army major, now raconteur on leadership matters and member of the New South Wales Parliament, Charlie believes strongly in the merits of pushing ordinary Australians to unimaginable mental and physical limits. By throwing together a group of strangers, and placing them into a demanding and dangerous foreign environment, Charlie believes his charges develop a powerful camaraderie; or in more typically Australian wartime vernacular: they forge the bonds of mateship. In no uncertain terms each individual quickly realises the goals that Charlie sets will not be achieved unless they unite as a team. The philosophy has become the essence of the Kokoda Challenge.

Charlie developed the programme in response to a personal belief that the leadership and team-building techniques employed by so many modern corporations are next to useless. Usually, says Charlie, this is because they adopt American and British philosophies which are irrelevant to, and inappropriate for, the Australian mind-set. He saves his strongest criticism for role-play style courses where trainees pretend to solve set problems or develop team harmony, more often than not in the confines of a plush hotel.

Instead, Charlie argues that only powerful, shared experiences like walking the Kokoda Trail seriously limit a person’s ability to indulge in self-aggrandisement. “The promotion of personal agendas is a significant hindrance to the successful completion of today’s team-oriented corporate and political goals,” says Charlie. Add to the equation the inspiration that comes from learning about Kokoda’s powerful wartime history and the net result is a unique programme that has caught the eye of corporate Australia. The Kokoda Challenge is an experience so profound it has the potential to affect participants for life.

The challenge starts out comfortably enough: you might say deceptively so. On a small island off Port Moresby two teams gather – one consisting mainly of CRA employees, the other a combination of Young Liberals and 16 to 20-year-old former street kids who, with help from Youth Insearch, have managed to restore meaning to their lives. The teams were to become Maroubra and Cha, in honour of the Australian forces that defended Papua New Guinea during World War 11.

“This is not just a trek, it’s a programme,” warns Charlie at his first briefing. “The programme is designed for you to work as a team and as any team you are only as strong as your weakest link. We know people can live in this environment for at least 27 days. Our Diggers proved that during the Kokoda campaign. Anything you take apart from what you are wearing now is a luxury. Remember, the more you take, the more the pain.”

Before leaving the teams to pack, Charlie throws up the first of many challenges – extra tasks he periodically assigns with the aim of making the next 11 days even more testing. “By the way,” he says, “we have some urgent medical supplies to deliver to Menari Village, and I have an assortment of sporting equipment for various villages along the way. You’ll need to find space for these also.”

So as the clock ticked toward midnight and the planned early start drew ever closer, Charlie left Maroubra and Cha to figure out how best to fill their packs. Clothing, food, camping equipment and personal first-aid kits make for a realistic weight. Then, as each tried to find space for the six volleyballs, six footballs, six baseballs, four soccer balls, six nets, six pumps, four frisbees, four stethoscopes and six large plastic bags packed with medicines, concerns grew. One last surprise addition, the bulky five-plus kilogram radio (described as an essential safety item), further heightened the sense of tension.

Rising towards Imita Ridge, where Japanese troops caught their first and only glimpse of Port Moresby before Australian troops forced them to withdraw, the Golden Staircase punctuates day one like a brick that strikes between the eyes. Far from golden, it boasts a muddy chute bound together with twisted roots, rising at gradients of up to 60 degrees. You don’t so much walk the track to Imita Gap, rather, you walk, crawl and clamber – hour after hour. Upon reaching the top, there is little more than four metres of flat ground before the path plunges, following an unforgiving hillside with sheer drops to the left. In the dead of night, beneath pouring rain, day one is risky business.

It is here that participants instantly realise the agony of Kokoda. Each starts to appreciate how critical effective teamwork will be in order to meet their goal. Self-doubt entrenches itself as the prevailing emotion. Every time a foot sinks into the slick brown mud and another step is taken, Kokoda ferrets out the true character, both good points and bad, of every individual.

Starting out hard, in control and confident, Ian Bell, from the CRA subsidiary Technical Services Australia, soon began to suffer. when asked how he felt, he managed few words, but his pale, sweat-drenched face spoke volumes. Similarly, Dr John found the going tough, his body straining beneath his weighty backpack. Karen Blaike, from Hammersley Iron, fared reasonably well at first – thanks not doubt to her experience as a triathlete. “However, I don’t know how I’ll go over the next few days,” she said not long into the walk.

Those concerns were to ring true when she discovered that no amount of swimming, cycling or running could have helped overcome her fear of Kokoda’s vicious downhill grades. In contrast, Dampier Salt’s Stuart Evans, quickly emerged as the team’s “action man”. Small, lean and in his early 40s, he proudly carried a photograph of his baby grandson. This proven ability to build and extended family at remarkable speed was matched only by the fearless manner in which he negotiated the rickety, slippery log bridges that straddled countless roaring rivers.

Maroubra’s 11 members, driven by the stress of night trekking and drawing from their corporate experience, began pulling together as a team not long after dark. they finally staggered into camp at 12.15 am. Cha group – younger, weaker and disintegrating through disorganisation – followed three hours behind. The terrible start had left every member shell-shocked and after having barely enough time to make camp and eat, let alone sleep, Cha set off on day two – once more in Maroubra’s wake. By late afternoon, two lines of sodden trekkers staggered on through another tropical downpour. Maroubra made painfully slow progress, while Cha went virtually nowhere. As every hour passed, the youngsters fell further behind schedule.

Charlie, whose name by this stage forms the focus of hatred and aggression, answers the inevitable question “how much further to go?” in one of two ways: “not far” or “it depends on how fast you walk”. He offers no tips and little moral support. As he watches the spirits plunge, he appears to fill with an almost macabre sense of satisfaction. Charlie is content, not because he is the cornerstone of 22 peoples’ hatred and suffering, rather he is witnessing the development of ordinary individuals in ways no-one would ever have though possible.

Widely acknowledged as a nightmare on foot, day two is mostly remembered as the most soul-destroying and painful experience ever. After an 18-hour slog, Maroubra made it to their destination, Nauro Village, at 2.30 am. They pitched camp and collapsed; the silence of the remaining night broken only by violent stomach convulsions from Tim Cameron. Just turned 21, Tim received the trip as a birthday present from his father. “He thinks I’m a smart arse and need some straightening out,” said Tim the next morning.

In contrast, Cha never arrived. Indeed, they had fallen so far behind that they didn’t even make it to an ominous note written by Charlie and posted on a stick next to a pile of rusty grenades and mortars on the rugged Maguli Range. “You must improve your rate of trekking,” it read, “otherwise tonight will be the worst night of your lives.” Cha spent another miserable night catching a few hours’ sleep somewhere south of the Maguli Range.

And so, life proceeds on the trail as it twists, turns and plunges, clings to narrow spurs and sinks beneath enormous bogs. While the jungle is thick, it’s surprisingly devoid of animal life and the only creatures offering a regular show are the vocal six-o’clock crickets. Emotionally, the trekkers rarely lift themselves above rock bottom until late on day three when Menari finally appears to those who can follow Charlie’s schedule; in a demonstration of his remarkable fitness, Charlie constantly moved backwards and forwards between both groups.

While Maroubra made it, Cha fell victims to an enormous deluge and, with a major river suddenly impassable, they had no choice but to overnight in a swamp. Resigned to her fate Edwina Pearce, one of Cha’s more bubbly members, stripped off and started bathing. Then for reasons unknown (put it down to delirium) she turned to Charlie and asked: (What are going to wear to bed.” No response was forthcoming. Always fishing for a lighter side to a crisis, Edwina would later describe the swamp by night, sleeping soaked and virtually naked, as “her most enriching experience ever.”

Menari, at 850 metres and surrounded by thickly forested peaks, is most impressive at dawn. Cool air, blue sky and damp ground from the evening rains create a buoyant atmosphere. Best of all, fresh cucumbers, corn and potatoes offered by friendly villagers carry the aura of delicate creations prepared by master chefs. While Maroubra ate and dressed their wounds Charlie, with help from porters hired along the way, pushed Cha toward Menari at a tempo the group had not yet experienced. They made it my mid-morning, and for the first time in days the entire party re-united. Finally, a sense of overwhelming elation replaced the gloom and suffering.

An original Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel, the name given to legendary stretcher bearers of the Koiari people who live along the track and carried wounded diggers to safety, greeted the ragged gathering. Wearing his wartime uniform with pride, Bokoi Faole spoke little English. Quietly, he accepted two footballs carried in by the trekkers and much more to everyone’s delight, the bulky medical supplies were also discarded. Then, on leaving, every last villager fell into line to participate in a custom where each trekker shakes hundreds of hands before departure. The practice lifted spirits another notch and the teams moved on toward the rain-swept and bitterly cold top of Brigade Hill, where Kokoda’s biggest and bloodiest battle was fought.

Although the entire trail stands as a memorial to the heroic actions of ordinary Australians, it’s Brigade Hill, along with a village called Isurava to the north, which Charlie insists must be singled out for special recognition. While Australians can never begrudge the sacrifice made by diggers who fought in Europe, Vietnam and all other theatres of war, Kokoda remains the only campaign waged in direct defence of Australian territory. It was a victory against all odds, where 1,000 largely inexperienced diggers repelled 6,000 elite Japanese troops who were widely regarded as invincible. Until Kokoda, Japan had not lost a single campaign.

From Brigade Hill, it is Charlie’s stories of unimaginable wartime achievements, of brilliant teamwork, leadership by example and ultimate acts of self-sacrifice which drive the trekkers forward. As night once again falls, and cold high-altitude air begins to bite, everyone knows that while they are doing it tough, Australians before them also had to endure bullets, bombs and crippling disease.

The two days to Myola quickly develop into an emotional rollercoaster equal to, or exceeding, the topographic extremes of the track itself. Having emerged from the “conditioning phase”, a process which Charlie says proves to everyone that Kokoda is not insurmountable, the walk becomes a nursery for growing self-confidence. Where muscles would have long collapsed, willpower takes control. That tiny, smoked-filled hut at Myola, the prospect of a bed, along with a day’s rest is the focus of all energy. Passing through delightful villages like Kagi, Efogi No1 and No 2, and Naduli, the reception is always genuine. The perfect harmonies of the Kioari people, their desire to sing and dance, and their ability to draw laughter from life’s simplest pleasures, move even the toughest characters to tears.

Then, only hours from Myola, the trail climbs above 2,000 metres, passes through a high-altitude forest dripping with moss and sinks into a kilometre-long swamp. Unlike previous afternoons, this time even rain becomes a liability. Dr John, who later described the final hours walking into Myola as his worst, came close to collapsing with hypothermia. With a frightening gait he dragged his feet through every step, his ankles and legs buckling outward under the strain. “When I get home, I’m going to go into the shower, lock the door, sit on the floor and wait until the water goes cold,” he decided. It was attitude alone that kept him going.

Suffering similar trauma, Cha group’s Hillary Williams says she’ll never forget arriving at Myola, exhausted, only to discover there were not enough beds to go round. “I tripped, did a fact plant in the mud, wet my pants and burst into tears,” she said. “It was just so humiliating. But the team helped me up and I pulled myself together.” The esprit de corps needed to make it through the swamp that night, along with the stress-induced bickering, followed by the successful arrival at Myola, were defining moments of the programme.

Early morning at Myola is surprisingly cold. With temperatures nudging zero, in another approach to teamwork many elected to seek warmth through sharing sleeping bags. By midday the trekkers gathered to exchange thoughts about those who had influenced their lives, participate in more formal leadership exercises and to hear another round of wise words from Charlie.

Dr John’s heartfelt description of his father depicted an average individual who had no choice but to endure considerable hardship. He survived the depression, World War 11, then made even more personal sacrifices in a bid to offer his children the best possible chance in life. The impact of adversity on Dr John’s father and the effect it had on his attitudes and beliefs are indicative of the ideals Charlie endeavours to project.

Like no other ingredient, Charlie stresses that adversity builds character. The pressures of economic depression and world wars helped many nations, including Australia, rise to their best. “Something has gone wrong over the past 50 years and one of the reasons is the lack of adversity,” says Charlie.

While Australians in the past have been admired for their team spirit and leadership skills, the 1990 OECD World Competitiveness Report revealed a less positive picture. Of 22 member nations, Australia ranked 19th, falling behind countries like Turkey, Spain and Italy. Reinforcing these statistics, the much-touted enterprising Nation Report, commissioned by the Federal Government in 1990, concluded that while Australia boasted strong technical skills, its management and communication skills were weak.

And so the trek continues. while the hardest is over, for another five days Charlie keeps everyone on their toes, forever setting extra tasks – like searching for crashed wartime aircraft and making side trips to out-of-the-way villages. In addition, the groups work more closely with their guides thus experiencing the apparently instinctive and ego-free way in which Kioari people work together to achieve an objective.

Charlie’s final briefing takes place in the tiny village of Isurava, the site where Australia’s forces first contacted the Japanese, holding them at bay for days. “It has been proven to me again that through adversity people can come together in a very short time, forever seeking to draw on the achievements of Australians in the past. That is the spirit of Kokoda and the spirit of Australia.”

Peter Beeh