The Rise, Fall and Future of Kokoda Tourism

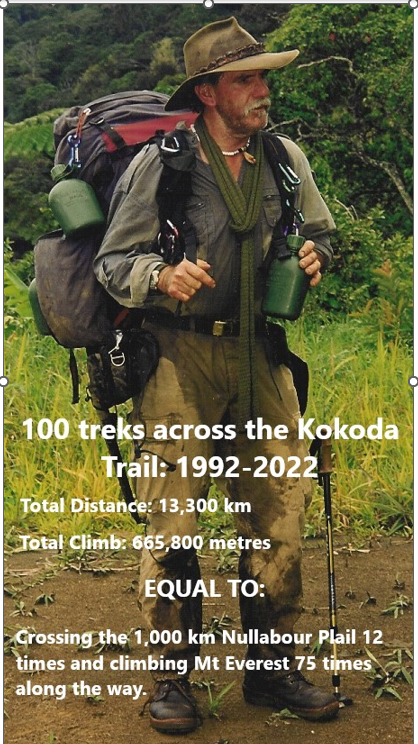

Over the past 32 years I have led 101 expeditions across the Kokoda Trail. During this time I have also travelled to Canberra to brief eight of the 11 Ministers for Veterans Affairs and three of the Ministers for International Aid and the Pacific, on the need to protect our shared military heritage across the Kokoda Trail. Unfortunately, there were no outcomes from these meetings.

I have also submitted numerous papers with suggestions for improving the management of Kokoda pilgrimage tourism. These were based on the collective experience of our trek leaders who have a combined total of 160 years professional military experience and who have led more than 600 expeditions across the Trail over the past 32 years. All have been ignored by DFAT environment officials in Canberra and Port Moresby.

Charlie Lynn

The Beginning

The Kokoda Trail lay dormant for 50 years from the time of the Kokoda campaign in 1942.

As the 50th anniversary of the campaign approached in 1991 I was invited by journalist, Patrick Lindsay on behalf of two Papua New Guineans, David and Bernard Choulai, to organize a race across it. Patrick was aware of the fact that I was a former army major, an ultramarathon runner, the organizer of both the Anzac Day Marathon in Sydney and the annual Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Ultramarathon (1984-91). I was also a NSW Ultramarathon record holder in 1987.

The opportunity appealed as I was the son of an infantry veteran who served in Milne Bay, Lae, and Finchafen in 1943. I was born in 1945 and the stories of the war in New Guinea helped shaped my character during my formative years.

I was also influenced by my own military service which included service in Vietnam and two years in Singapore where I visited Changi prison and Kranji War Memorial many times. I later visited every Civil War battlefield in the United States during my two years as an exchange officer with the US Army. I was obviously impressed with the way the British and American Governments honoured their military heritage.

I expected a similar reverence to the Kokoda Trail when I began my initial research, however it was not to be. There were no topographical maps, virtually no information on the physical Trail itself, and limited information on the campaign.

After my lone trek with a local guide in 1991 I found it difficult to find words to explain the experience. I also found there was little corporate interest in sponsoring a race across it at the time as ‘Kokoda’ was not on the public radar.

The law-and-order situation in Port Moresby was also a factor.

Public commentary in the early 90s referred to the Melanesian ‘arc of instability’ to our immediate north and the prospect of PNG becoming a ‘failed state’. The city itself was hidden behind razor-wire and a night curfew was in place. Convoys of security personnel with guard-dogs arrived in the city late in the afternoon and before nightfall there didn’t seem to be an entrance that was not guarded.

Interest in Kokoda was aroused with the announcement that Paul Keating would become the first Prime Minister since the war to attend an Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery and lay a wreath on the Kokoda plateau.

There was a flurry of excitement within PNG tourism who hosted numerous meetings in the lead-up to the anniversary. They were expecting a large influx of visitors and wanted to make the most of it. As it transpired the numbers never eventuated, which was a blessing because there were no outcomes from any of the meetings!

By this stage I had concluded that the only effective way to understand the Kokoda Trail was to have people trek across it.

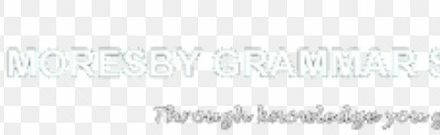

With this in mind I sent out 1500 corporate invitations to join a commemorative trek for the 50th anniversary of the campaign. I received one corporate acceptance which led to the following article in the Sydney Morning Herald:

As a result of the article I received a further 17 individual enquiries and the Bulletin with Newsweek magazine decided to sponsor a reporter and photographer to accompany us.

Paul Keating’s unexpected gesture of dropping to his knees and kissing the ground at Kokoda was featured on every news outlet.

Military historian, Dr. David Horner, who Accompanied Keating on the flight to Kokoda wrote:

Some twenty-five years ago, on 26 April 1992, I flew over the Owen Stanley Range in a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) C-130 transport aircraft with Prime Minister Paul Keating as his historical adviser. We landed at Popondetta and then boarded an RAAF Caribou for the short flight to Kokoda. Along the way I tried to describe the Kokoda campaign to the Prime Minister, who, I must say, absorbed the facts and figures with commendable speed and accuracy. At Kokoda Keating was scheduled to lay wreaths on the memorial stones to the troops who had fought on the Kokoda Trail. He duly laid the wreaths on the ‘official’ memorials, but then moved to an unofficial memorial with plaques from the different battalions that had fought in the campaign. While I explained what the battalions had done, Keating said to me, ‘I haven’t got a wreath for this one -; what will I do?’ Before I could gather my thoughts, he stepped forward and kissed the ground at the base of the memorial stone. For a moment I thought he had had a heart attack and had fallen over. The Prime Minister then moved to a dais and delivered a speech, which as far I could see was given ‘off the cuff’. Among other things, when referring to the Kokoda battles, he said: ‘… this was the first and only time that we’ve fought against an enemy to prevent the invasion of Australia … This was the place where I believe the depth and the soul of the Australian nation was confirmed.’ The previous day at a ceremony in Port Moresby Keating had expounded on the same theme, stating that Kokoda was ‘the most famous battle in Australia’s history’. He continued that the Australians in Papua New Guinea ‘fought and died, not in defence of the old world, but the new world … it might be said that, for Australians, the battles in Papua New Guinea were the most important ever fought.’ At a luncheon held after the Kokoda visit, Keating said that the morning had been ‘the most moving day of my public life’.

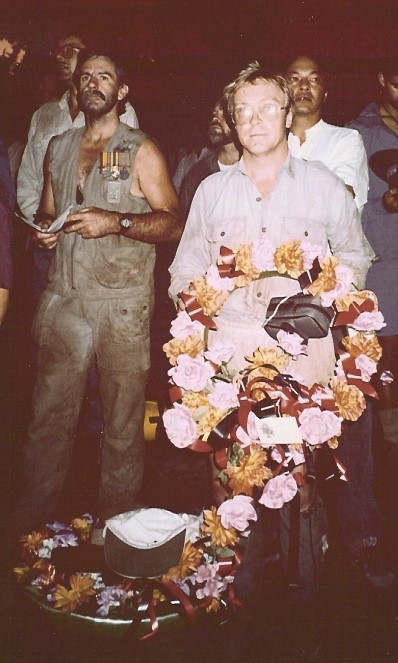

Our group, which had trekked from Kokoda to Owers Corner, then a further 40 km to the Dawn Service, caused the Prime Minister’s delegation and accompanying media pack to part at Bomana War Cemetery when we arrived to lay our wreath – obviously due to the pungent smell that permeated from us.

The Bulletin article, along with Keating’s actions and patriotic speeches, led to a national awakening of the significance of the Kokoda campaign when the fate of our nation was in the balance.

It also awakened my mind to a conscious desire for Australians to know more about the campaign.

It was such a profound experience the magazine published it as a cover story, ‘Kokoda-A Walk on the Wild Side’, with a five-page article.

In 1994 I submitted a paper to both the Australian and PNG Governments calling on them to recognise the benefit of developing Kokoda as a pilgrimage tourism destination:

‘In the short term PNG should focus its tourist development on its natural assets – the country and its people. And it should develop policies to cater for the niche adventure market.

‘The Kokoda Trail is an ideal model. The trail has a special aura because of its significance in the war. The rugged beauty of the Owen Stanley Range and the nature and disposition of the villagers along the trail are unique attractions to the adventure tourist.

‘Tourism along the trail will create social and economic benefits for the villagers. Local guides will be employed, food will be procured, accommodation will be used, and artefacts will be purchased.

‘The 50th anniversary of the campaign across the Owen Stanley Range is a unique opportunity to refocus international attention to the challenge, the rigours, and the people of the Kokoda Trail. It provides an opportunity for the government of PNG to establish a model for adventure tourism which would otherwise take many years to establish’.

As a result of the publicity we generated more trekkers began to cross the Trail, but, apart from some random purchases of local fruit and vegetables, village communities were receiving few financial benefits from them.

This led to some pent-up emotion which culminated in the closing of the Trail at Kovello village in November 1992.

I was leading a group of Australian journalists to attend the 50th anniversary of the raising of the Australian flag at Kokoda but we were prevented from passing through the village on our final leg.

I went ahead with half-a-dozen of my guides to discuss the issue and their grievances. The discussion could best be described as hostile as many of the menfolk took it in turns to confront me with raised voices, angry gestures, and the odd spray of betel-nut spittle.

Their complaints were based on the fact that the Australian Government had built a hospital, museum, and a guesthouse at Kokoda, but nobody from Kovello was employed so they wanted their own hospital, museum, and guesthouse!

After a tense period, the villagers settled down and we discussed the benefits they could receive from trekking. We also agreed to employ a few guides and carriers from the village on our future treks and do our best to represent their views back in Port Moresby. The following year we funded the construction of a small kindergarten for them.

The pilgrimage included an unexpected participant, Corporal Les Cook, a Kokoda veteran who had fought with the 2/14th Battalion during the crucial stages of the campaign – he celebrated his 100th birthday on 10 January 2023 – however, according to army records he is 103 years old because he put his age up by three years so he could enlist.

The Canberra Times

Canberra Times journalist, Marion Frith, captured the essence of the trek in her article: ‘A Hard Slog to Kokoda’ published in the Canberra Times on 15 November 1992:

‘WE ARE indeed a strange collection of life’s assorted gathered here so far from home’.

‘Checking our packs, checking out each other. Among us are the media’s most unfit, a professional fisherman, a surgeon‐cum‐ardent bushwalker, a marathon runner and a 70‐year‐old war veteran. We are on a pilgrimage for which, it turns out, we are largely unprepared.

‘Our reasons for being there are many: some of us have been lured by the historical significance on this the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign, others by the challenge of a “walk” (ha!) regarded as one of the most difficult in the world, and I and one other are retracing the awful steps taken by our fathers before we were born. Les Cook, of Garran, a veteran of the bitter battle, is there because, he says, he could not pass up the chance to come back and see it one more time.

‘We have been herded together by an extraordinary man, Charlie Lynn, a retired Army major, who runs a company called Kokoda Epic. He is a passionate blend of adventurer and zealous patriot with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the Papua‐New Guinea campaigns and an unswerving commitment to enshrining Kokoda and all it represents in the minds and hearts of ignorant Australians. . .

‘Between Charlie and Les the horrendous jungle track and the war which raged so viciously across it come to life. Charlie’s moving accounts are coloured with Les’s lively recollections. “This is where the Australians were butchered in their pits,” Charlie will say. “My mate lost his last tin of rations down that hill,” Les says. And together they guide us for a week through a moment in history that shaped a generation and cost it its innocence. . .

‘The pack of us that has fallen to the back of the group are slow and suffering. We stop constantly, cramping and aching. When will it end? By late afternoon it is raining steadily and we have not even made the ascent: there is a long way to go. Night begins to fall, as do my tears.

‘Charlie steadies me with a cuddly and some food. “Come on mate,” he says. “You can do it.” But I don’t want to do it and I don’t want to be there. I want to go home.

Still we creep on. We are blanketed in darkness and lonely torches compete with armies of fireflies beneath a thick jungle canopy that censors any hope of starlight.

‘The “up” eventually becomes an equally horrendous down and we put nervous muddy boot after nervous boot, conscious that every step has the potential for injury. Where does our energy – pathetic and all but spent – continue to come from? How is that we are able to move at all?

‘Still, the camaraderie that descends upon this miserable caravan of lost souls is warm and enveloping. Those with torches light the way for those without, those temporarily firm on their feet support those who continually fall, those still able to muster a meagre dose of fleeting good cheer share it round in exchange for a last morsel of chocolate.

‘Finally, almost 16 hours after we set off that morning, we reach the village that is camp for the night. Charlie shepherds us in, he is tense and concerned. He had not reckoned on us being this bad. I collapse beside the fire, sobbing and shaking. My body is in spasm and I hear the nurse in the group mutter something about shock.

‘Suddenly tender hands that just 24 hours ago belonged to strangers are upon me, pulling off wet clothes, finding dry ones, holding hot tea to my lips and pressing a bowl of warm mush into my hands. Someone has laid out my sleeping mat, someone else is quietening the fast swelling number of hysterical pledges to pull out. As a group we are close to being out of control. We have lost it. . .

‘INCREDIBLY I am not broken – just broken in – and I wake to find that the despair of the night before has evaporated into the mist hanging over the valley. A group of solemn‐faced children have put themselves on sentry duty by our camp and a newborn baby, her head kissed with the first buds of tight black curls, lies in her shy mother’s arms. . .

‘The rest of us will see how we go, and for the first hour or so the countryside does its best to woo us as we snake through paradise‐like village gardens and cross crystal rivers and rickety log bridges. The idyll is short‐lived and by midmorning we are once again entrenched in the seesaw of sickening climbs followed by hairy descents.

‘Psychologically, however, something has shifted within most of us. Our whingeing has waned: we know we do not actually want to give up. If we survived the day before we can survive anything, and our bodies are spurring us on by proving they have purged themselves of the worst of the pain.

‘We never stop hurting, but few of us hurt like we did and a numbing exhaustion gradually replaces the jabbing pangs. One hundred kilometres through dense jungle? We are now really aware of just what that means, of just how hard it will be, but we are also aware that if we want to do it we probably can, it is up to us.

‘There are things we need to call on from within ourselves – grit and determination, Charlie calls it – and things we need to draw on from the group – support and friendship – in order to meet the challenge. . .

‘The next day we walk and walk, up one of the toughest rises yet, down some of the worst.

‘We try to stop quantifying. What is worse, anyway? All the climbs are mongrels and even on a good day there is nowhere I ever want to be except out of there. But something keeps us going, keeps us dragging foot after foot. Every step completed is one that never has to retraced.

‘Up, down. Up, down. Around, across. Up, up, up.

‘That afternoon we reach our nirvana – the village of Naduri. It is the home of our guides and we arrive to a hero’s welcome. Les leads us triumphantly in and we are met by the village elders – the original war‐time “fuzzy‐wuzzy angels” who carried the injured Diggers out against all odds down dangerous narrow mountain tracks.

‘A feast of food and flowers is laid out for us: mandarins, sugarcane, baked and steamed taro, pumpkin tops, potatoes, spinach.

‘We fall quiet as these old men stand tall and proud. Charlie seizes the moment, the women and children are banked up around, and in a gesture that cuts across cultures and through language barriers he recites the poem that immortalised these angels. The old men beam, and our army of trekkers wipe away tears.

‘It is as if we have arrived. Somewhere, anywhere. Our guides sit with us, their families join us, and the village and its people become imprinted in our hearts. Another woman and I join the evening church service and are entranced as the pastor, his face illuminated by a hurricane lamp, recites the prayers in pidgin and the children’s voices rise in harmony so sweet we never want it to end.

‘We are silent as we get up from the rough‐hewn pew. At that moment we have experienced life at its most perfect, superb in its simplicity, and suddenly we realise that the walk was worth it, if only to find this. Peace and joy are tangible, if fleeting, qualities and we know that where we are going to, where we have come from, we will probably never find it again. We want to seal the village in barbed wire and never let the world touch it. . .

‘When we finally enter sleepy, tiny Kokoda, drenched in sunshine, we are surely as triumphant as the troops who re‐entered it that same morning 50 years before. We assemble at the commemorative ceremony, attended by a lowly Australian Government minion and a handful of veterans and as the Last Post sounds pitifully on a crackling portable tape recorder we are truly moved. We have done it. We understand as only those who have done it can. Our peace‐time journey has tested and pushed us as we could never have imagined. The silent respect we pay to the young men who served and suffered along the path we have crossed is deep. As we clamber aboard the truck that has come to take us to the airport we have no doubt we are now invincible. We have plummeted to our worst lows and soared to our greatest heights . . .

‘There is nothing physically or emotionally we cannot endure. We had set off as 34 individuals, half of us Australians and half of us Papuan villagers. When we part we are friends – an indivisible and strong unit for whom farewells come hard.

‘If the spirit of Kokoda is strength in adversity, courage and mateship that spirit has been seeded in us all. We cross in a brief 20 minutes what has taken us eight gruelling days.

‘And like all those who crossed it before us, who left their souls in the mud and the heat and the terrifying jungle, few will ever go back.

‘Charlie, of course, is the exception. He will continue to pluck other ordinary humans from their comfortable lives and help them blossom into indefatigables, drawing on the greatness that lies largely unchallenged within us all. For the rest of us though, Kokoda will become just one humbling week in our lifetimes: albeit our whole lifetimes lived in just one unforgettably humbling week.’

Similar articles recounting the experiences of fellow journalists on the trek were published nationally in The Australian, The Daily Telegraph, and the Sunday Age newspapers.

In 1994 I submitted a paper calling on our Federal government to proclaim the Kokoda Trail as a National Memorial Park:

‘Any plan that is developed should consider the fact that PNG does not have a welfare system and the Koiari and Orokaiva people who live along the track operate a subsistence economy. They are also the custodians of the land on which the battles that saved Australia were fought. ‘If we develop our long-term plan around providing a regular source of income for them we can be assured that they will protect and honour the battlesites we restore, the educational memorials we build and the village museums we assist with.

‘The objective of the master plan should therefore be to develop a self-sustaining eco-adventure trekking industry for the Koiari and Orokaiva people who live along the Kokoda Trail.’

It was difficult to progress the idea as the responsibility for such a plan did not fit neatly into a single Ministerial portfolio.

Canberra’s Apathy towards Kokoda: 1992-2002

It was also increasingly evident that, despite Prime Minister Keating’s fine speeches a few months earlier, and despite my numerous requests for a Military Heritage Master Plan for the Kokoda Trail, the political caravan had moved as the following extracts from Ministerial correspondence attest:

4 November 1992:

‘While the proposals you have outlined in your letter of 25 August (1992) to the Prime Minister have undoubted merit, I can give no undertaking that anything of that nature would fall within the scope of the commemorative measures now under consideration’.

The Hon Ben Humphreys MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

22 February 1995:

‘The Government’s philosophy is to commemorate and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the end of World War 11 with activities here in Australia. The only specific events relating to ‘Australia Remembers’ planned for overseas are three small pilgrimages of Australian veterans.’

The Hon Con Sciacca MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

24 June 1997:

“As a result it is not possible to award the Civilian Service Medal to the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’ at this distance in time.’

The Hon David Jull MP

Minister for Administrative Services

10 November 1997:

‘Your suggestion to form a small working group has merit. However, I do not recommend proceeding in this way at this time.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

11 December 2000:

‘Your proposal to develop the Trail is unfortunately outside the scope of the Australian aid program.”

Senator Kay Patterson

Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Foreign Affairs

7 December 2000:

‘With these limitations in mind, I regret I am unable to offer any prospect of achieving the all-of-government approach you seek in the time frame you propose.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

13 January 2001:

‘I believe you have presented to the Government an excellent proposal and initial plan to establish the Kokoda Track (or Trail) as a National Memorial Park – long overdue!’

Stan Bisset AM MC

President, 2/14th Battalion Association

7 February 2001:

‘Because of the above reasons and in consultation with the Chiefs of the villages along the Trail, I demanded a compensation of A$2,000,000.00 for developments along the Trail. This was not for Oro Province as a whole. However, after receiving your letter, I held discussions with the Chiefs and Councillors from the area and explained the contents of your letter in which I must say, all leaders from the area are happy with your efforts in going as far as preparing a proposal which is now before the Australian Government to develop a Master Plan for the development of the Kokoda Trail as a National Memorial Park.’

The Hon Sylvanus Siembo MP

Governor, Oro Province

18 February 2001:

‘It will come as no surprise to you then that the ‘Government Master Plan’ of which you inquire ‘for the development of the Kokoda Track as a national memorial park’ does not exist . . . I regret that I am unable to satisfy your demand for such a large scale approach to this issue.

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

8 March 2001:‘

The Australian High Commission in Port Moresby welcomes Mr Lynn’s enthusiasm and commitment to develop the Kokoda Track. We acknowledge the contributions he has made in the past and note that he is highly regarded in a number of communities for his assistance. Like many Australians, he has a strong belief in the Track’s historical importance and can see its potential as a source of revenue for local people and of education and personal development for young Australians in particular. My staff and I have met with Mr Lynn on a number of occasions during his visits to Port Moresby, and we accept that he is pursuing his proposals in order to advance what he believes is in the best interests of the Kokoda Track and its people.’

H.E. Nick Warner

Australian High Commissioner to Papua New Guinea

19 March 2001:

‘Your interest and commitment to the development of the Kokoda Track reflects your strong desire to improve the living conditions of its communities. In this regard our High Commissioner to Papua New Guinea greatly values your interest and suggestions, especially with respect to small-scale projects that might fit into their preferred strategy currently being developed. I trust this letter will be useful in finally resolving the issue of why my Department will not promote the creation of a National Memorial Park.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

9 May 2001:

‘I have noted your advice that the Papua New Guinea (PNG) Minister for National Planning is enthusiastic about your proposal. However, I believe the master plan you seek is a document most appropriately compiled by the Government of PNG. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs may be interested in contributing to such a process that would provide aid and development initiatives to provinces along the Kokoda Track. But it is a matter for the Government of PNG to decide if a master plan is appropriate and what organisations might be represented on any committee brought together for the preparation of such a document. Consequently, I trust that you will understand why I will not be selecting staff from my Department to participate on your project team.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

17 May 2001:

(Response to The Hon Dr Brendan Nelson MP, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Defence)

‘In view of the current situation on the Kokoda Track it would be inadvisable for the Australian Government to promote a proposal for the Track’s development. The subject of Mr Lynn’s proposal is a matter, in the first instance, for the Government of PNG. It would be inappropriate for a group of Australian bureaucrats to walk the Track and develop a master plan in isolation to the situation on the ground..’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

17 May 2001:

‘Thank you for your e-mail of 24 April 2001 to a number of Members of Parliament, Senators and others, regarding your proposal to create a Kokoda National Memorial Park in Papua New Guinea. I have previously explained why I do not support your proposal at the present time and trust that you will refer to my earlier letters on this matter. Mr Nick Warner, Australian High Commissioner to PNG, has provided advice that your proposal is premature and inappropriate at this stage.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

16 July 2001:

‘Having discussed this matter with representatives of the Papua New Guinea Government I have found no support for a park along the lines you have suggested. Other options were discussed but, in view of the social problems in the area associated with the Track, these alternatives have not been developed.’

Senator Robert Hill

Minister for the Environment and Heritage

10 August 2001:

‘As far as I am aware, the social problems associated with the track are continuing. Until such a time as these can be resolved by the people and Government of Papua New Guinea, and there is official PNG Government support for a memorial park, I am unable to consider expending resources and staff to work on a project team as you suggest.’

Senator Robert Hill

Minister for the Environment and Heritage

18 September 2001:

‘In previous correspondence, I have stated clearly that no such trek will be taking place while the security situation in the area remains uncertain and current High Commission travel advisories are in place. Further, officials and advisers on this issue have no need to embark on such a walk at public expense to capture the obvious importance of appropriate memorials being established along the Track. All members of the committee have a comprehensive understanding of the significance of the Track and what it means to the Australian community . . . the intend of the inter-departmental committee is to consider all proposals for the Track and to develop a co-ordinated response for consideration by this Government. Therefore and trek along the lines that you have proposed would be inappropriate, unnecessary and could be deemed as prejudicial to the deliberations of the committee.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

28 September 2001:

‘I appreciate that there would be a great deal of planning required for such a trek but wish to reiterate that no such trek will be taking place while the security situation in the area remains uncertain and current High Commission travel advisories are in place. Further, members of the committee are already aware of the significance of the Track and the importance to the Australian community.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

17 October 2001:

‘With regards to the trek, I wish to reiterate that the IDC is aware of the significance of the Kokoda Track and that as I advised previously, no such trek will be taking place while the security situation in the area remains uncertain and current High Commission travel advisories are in place.’

The Hon Bruce Scott MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

26 October 2001:

‘The IDC currently has no plans to take part in a trek across the Track. All members of the committee have a comprehensive understanding of the significance of the Track and what it means to the Australian community.’

Dr Peter Poggioli

Chief of Staff to the Minister for Education, Training and Youth Affairs

29 October 2001:

‘Thank you for the recent information you sent regarding your proposals for the ‘big picture’ plans for the track and I wish you well. I agree that the Minister for Veterans Affairs is a hard person to deal with having spoken with a lot of the veterans and also seen the problems we have had. Good luck with getting politicians to cross the track . . . The problem I see is that without a co-ordinated approach, everyone goes off doing their little bits and it all gets confusing. A lot of people aren’t aware of the problems that occur in PNG in trying to achieve outcomes, etc. After 3 years living there, the real problems of corrupt and unintelligent government members, cronyism, wantokism, compensation and cargo cult become very apparent. Anyway Charlie, I wish you luck and if there is anything I can do to assist, please let me know.’

Ian Hopley

Australian Police Advisor in PNG

Executive Committee Member and Trustee, 2/14th Battalion Association

27 November 2001:

‘I am pleased to advise that the National Executive of the RSL has endorsed the proposal to establish a master plan for the development of the Kokoda Track Memorial Park. Thank you for taking the time to address our National Executive and for the personal effort you have put into promoting this concept.’

Major-General Peter Phillips AO MC (Retd)

National President, Returned Services League

25 January 2002:

‘Thank you for your letter of 6 December 2001 congratulating me on my recent appointment as Minister for Veterans Affairs. . . In response to you invitation to discuss your proposal for the development of the Kokoda Track as a National Memorial Park, I wish to endorse the comments of my predecessor. The inter-departmental committee (IDC) on Kokoda is currently considering all proposals for the Track and developing a co-ordinated response for consideration by this government.’

The Hon Danna Vale MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

30 July 2002:

‘I do however wish to draw your intention to the fact that the inter-departmental committee report was established to examine Australia’s interests in Kokoda Track Development and to determine ways to enhance public recognition of its importance to Australians. Whilst the IDC included provision in the longer term for outlining a process for cooperative development, its purpose was not to develop a master plan for the future development of the Kokoda Track. . .’

The Hon Danna Vale MP

Minister for Veterans Affairs

Channel 9 Celebrity Anzac Trek – 1996

In January 1996, I was invited to lead a group of television celebrities including Angry Anderson, Darryl Braithwaite, Collette Mann, Dermott Brereton and Grant Kenny across the Trail for Channel 9.

After the program featured on Anzac Day it achieved the highest ratings ever recorded by ‘A Current Affair’ with almost 3 million viewers.

This confirmed my view that Australians wanted to know more about their military history.

While the Channel 9 television program led to a resurgence in public interest in the trek it created a personal financial and logistic dilemma as the Australian Government was ambivalent about the Trail, the PNG Government had more pressing social issues to deal with, and there was no inbound tourism organisation in place.

As a result, our logistics were organised from our home in Camden. All meals had to be prepacked in our kitchen. Backpacks had to be carefully prepacked and marked by the day. Our trek uniforms had to be organised and tagged. On the morning of departure, I had to hire a trailer, pack up to 50 backpacks, drive them to the airport, get them through customs, and hope that my wife, who had never driven a vehicle with a trailer attached, would be able to negotiate the peak hour traffic back home.

The flight from Sydney to Port Moresby was often the only chance I had to catch up on some sleep after a frenetic 48 hours’ preparation.

The situation was reversed after my arrival in Port Moresby. I had to explain to customs why I had so much baggage, convince them I had 25 Australians following me the next day who would contribute to the PNG economy, etc. etc. Then unpack and repack most of the gear in my room at the Gateway Hotel.

On the Trail

On the Trail trek we have a duty of care to our trekkers to ensure the Trail is safe and campsite facilities are adequate to meet their needs. This was the basis of our original proposal for a management body to be established in PNG and for trek fees to be introduced to meet these two basic requirements 20 years ago in 2003.

During our treks we are responsible for the welfare of our trekkers and our PNG support crews in the rugged and remote area across the Owen Stanley Ranges.

Our day starts at 4.30 am when we wake to rouse our trekkers for the day ahead.

Prior to departure we brief our PNG support crew on the logistic requirements for the day, and brief our trekkers separately on the terrain, safety, villagers, and historic sites they will visit – then provide detailed historical briefings at each one. We also attend to any medical issues trekkers might have before hauling our own packs onto our backs to lead the group.

During the day we have to assess the dangers of river crossings and landslides; be alert to the possibility of emergency medical evacuations and implement our plan whenever and wherever it is required. This can cause significant delays at the evacuation point and put us under considerable physical pressure as we then have catch up with our group.

There are invariably one or more stragglers during the day. This causes us to stay behind with them which often involves late night arrivals into camp.

During peak trekking periods we have to secure our campsites by sending a PNG team ahead of the group – and often get involved in heated discussions with other trek groups who have not pre-arranged to stay at the site which does not have the capacity to accommodate them.

This is because KTA staff comfortably parked in their swivel chairs behind remote computer screens in Port Moresby have not been able to work out how to implement a basic campsite booking system, or a trek itinerary management system, or a campsite development plan, or a trek itinerary management plan, or even a single hygienic toilet to meet the needs of their paying customers over the past 14 years!

By the end of our 10-day trek we will have averaged around 16 hours per day, trekked a total distance of 152 km, climbed a total of 7150 metres, and descended 7570m.

Then begins the clean-up as gear has to be accounted for; tents, sleeping bags and mats washed, dried and repaired where necessary; medical stores to be rehabilitated; funds to be acquitted; surveys to be distributed to trekkers; etc., etc.

Notwithstanding this, leading treks was the easy part of the whole operation due to the professionalism of our PNG support crews who truly are masters of their environment and who welcome the opportunity to earn some money in an economy that seemed to be well and truly busted in the mid to late 1990s.

I hung in, despite Jill’s concern that we were in the red zone of our credit card limit, because I believed the emotional impact of the pilgrimage, the physical challenge, the authenticity of the jungle environment, and the link to traditional villagers, would appeal to dinkum Australians.

Negative media reports and ‘Traveller Alerts’ in Australia caused deep resentment among PNG Government officials who had their work cut-out restoring order. Our patronising attitude culminated in the frisking of PNGs much loved Grand Chief, Sir Michael Somare, by security goons at Brisbane airport. It was regarded as a national insult.

PNG was not therefore regarded as a favourable place to do business.

Landowner Frustrations

As the number of trekkers began to increase so did the frustrations of traditional landowners and their village communities who were receiving few financial benefits as there was no mechanism in place to identify their needs and desires.

This culminated in Oro Provincial Governor, Sylvanus Siembo, closing the Trail after the Sydney Olympic Committee did not support the Olympic Torch being run across the Trail enroute from Athens in 2000.

I met with Governor Siembo in his parliamentary office in Port Moresby and found him willing to negotiate an outcome that would benefit his people. I outlined my proposal for a trek permit fee to be introduced to enable village communities to get a more equitable share of benefits from the increasing interest in Kokoda Tourism.

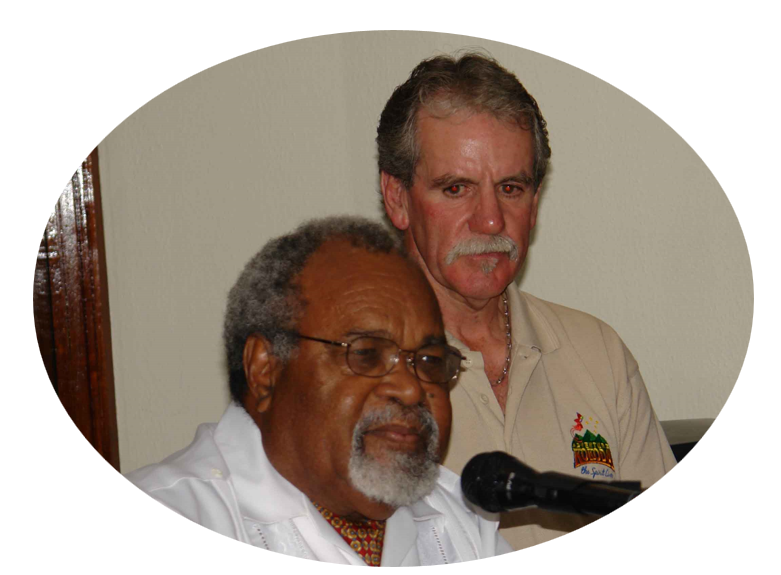

He accepted the proposal and the Trail was reopened at a special ceremony attended by Kelvin Templeton and myself in Kovello village. I was honoured when Governor Siembo presented me with a traditional headband:

‘This headband that I have put around your head is a symbol of a chief and is sacred. It is only worn by chiefs in the Oro Province. This headband you wear marks you as one of the chiefs of the Orokaiva people because of your hard work to my people in our endeavours to reaching a lasting solution to the famous Kokoda Trail closure. This headband and necklace that I presented to you today marks our brotherly relationship and a lasting memory to live on in future generations to come.’

Meeting the Grand Chief

On 15 November 2002, I was invited to a private meeting with the Prime Minister of PNG, Sir Michael Somare at the Sheraton on the Park Hotel in Sydney by the PNG High Commissioner, H.E. Renagi Lohia.

I was asked if I could arrange a meeting between Sir Michael and the NSW Premier, Bob Carr.

I was able to do this and the following day I escorted the Prime Minister to the Premier’s office and introduced them. I believe this was the start of a close relationship between them.

I received the following note from the Premier after I wrote to thank him for hosting the meeting at such short notice:

‘Dear Charlie,

‘I’ve always been impressed by your love of the Track and your determination to ensure its place in the Australian imagination is never lost.

‘You know better than most that the Kokoda Track isn’t just a place where our salvation was won – though we should remember and document and treasure every inch of it. Kokoda’s now part of the Australian Dreaming, a sacred site.

‘More than that the Men of Kokoda are among the greatest of heroes in a land that rightly canonizes few heroes. And as time slowly steals the survivors from our midst, it’s hard to resist thinking that Australians in the not too distant future will look back with almost disbelief at the giants who lived in those days.’

The continued lack of any sort of management system allowed the ‘law of the jungle’ to prevail while landowners became more frustrated as their interests were ignored.

Australian High Commissioners in Port Moresby, Nick Warner, and his successor, Michael Potts were aware of the situation but unable to implement any sort of management system without the consent of the PNG Government.

I then approached Sir Peter Barter, the PNG Minister for Provincial and Local Government Affairs and Intergovernmental Relations, to seek his support in establishing a management body. This was new ground for PNG as there was no precedent for operating such a place as a National Park.

Sir Peter therefore established a ‘Kokoda Track (Special Purpose) Authority’ which became known as the KTA. Unfortunately, he was not able to provide any funds to support the new body and there was no interest in the enterprise from the Australian Government.

My company, Adventure Kokoda, provided an advance of $10,000 to engage a CEO and establish an office facility. Mr Warren Bartlett, a former Kiap who was providing our logistic support in PNG, was engaged on an annual salary of $12,500, and provided with a part-time assistant.

A Board of Directors was duly appointed however they had no qualifications or experience in commerce, governance, tourism, or trekking. This would soon lead to serious challenges for the CEO who had to seek to protect the finances of the KTA from them.

A trek fee of K200 was introduced. It was bitterly opposed by some eco-tour companies which added to the initial stresses Bartlett had to deal with in his endeavours to bring a degree of order to the trekking industry.

Sir Peter later wrote:

“Without Charlie Lynn’s dedication to the people of the Kokoda Trail, and Papua New Guinea in general, and his assistance in early negotiations in the establishment of the Authority, the establishment of the Kokoda Track Authority and its future plans for assisting the sustainability of the Kokoda Track Tourism Strategy and its heritage, there would be no special purposes authority – it would still be sitting in limbo.”

I was convinced that if traditional landowners received a site-fee from trekkers they would protect and maintain them. During this period, I had led several mapping expeditions across the Trail where I rediscovered the original Brigade Hill and Isurava battlesites which had been bypassed and reclaimed by the jungle over the years since the war.

Kokoda Track Foundation

My position as an elected Member of the NSW Parliament provided me with a platform to organise some large fundraising functions based on an annual ‘Ralph Honner Oration’ at Parliament House. These were well patronised, and we raised significant funds for the Foundation.

I invited a small number of Sydney based trekkers to join me on the Board of Directors which I chaired.

I had also discussed the opportunity for a group of AFL footballers from the Sydney Swans to trek Kokoda with the CEO, Kelvin Templeton, a former Brownlow Medallist. During our discussions I learned that Kelvin had a strong intellectual interest in indigenous affairs.

We then discussed the opportunity to run a series of workshops with key stakeholders along the Kokoda Trail and within the trekking industry, in Australia and PNG, to develop a strategic plan for the Trail.

We agreed that I would raise the funds necessary to support the workshops and he would enlist the support of Dr Stephen Wearing from the University of Technology in Sydney. Dr Wearing is a leading academic in the field of sustainable eco-development in Third World countries. He then enlisted the support of Paul Chatterton from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in PNG. Paul was a long-term advocate for the protection of pristine rainforest and endangered species in PNG. He was also fluent in Tok-Pisin.

Natalie Shymko, a staffer in the NSW Parliament who had previously trekked with me, volunteered to record our workshops and meetings.

I was able to raise approximately $200,000 to cover the cost of workshops in Sydney, Port Moresby, Efogi village and Kokoda. It was hard yakka as the Board I established to assist with raising funds were more adept at giving advice than generating dollars!

I eventually had the opportunity to present our strategic plan to Prime Minister Sir Michael Somare at a private function in 2006.

I also submitted it to the Minister for Veterans Affairs but did not receive a response.

Natalie Shymko maintained detailed records of all workshops conducted in Sydney, Port Moresby, Efogi village, and Kokoda. These are recorded in Chapter 8.

My emphasis on our shared military heritage and the commitments I made to local communities along the Trail during my treks had created tensions within the Board as they had little appreciation of the reality of the ‘Melanesian Way’; none had any experience of the reality of dealing with PNG; and none had served in the military.

I was consistently advised of the need to have local communities relay requests for support to the Board for consideration as part of our approval process. They were unaware of the difficulty of explaining this approach while I was surrounded by hostile villagers waving machetes and spitting betel nut as part of their normal ‘negotiating process’. They invariably wanted some form of commitment before they would allow our groups to continue. At that stage I was involved with politics on a daily basis in the NSW Parliament and didn’t have the appetite to be involved in the politics of the Board I had created.

I therefore resigned from the Foundation and asked that my name be removed from their records as it was becoming increasingly clear they would prefer to be a quasi-aid agency further afield in PNG than a protector of our shared military heritage across the Trail.

This was confirmed by Dr Nelson in her interview with Dr Bino:

‘The formation of the Kokoda Track Foundation (KTF) could be viewed as an effort to achieve these goals, and so could the subsequent decision to remove the Australian based trek operators from its board of management, since this would remove any perception of bias in the way that it managed the donations (interview, Dr Genevieve Nelson 2011)’.

Dr Nelson neglected to advise Dr Bono that I had developed and funded the concept of the philanthropic body; that I had introduced her to the Trail; led the two treks she participated in; funded her first visit to PNG as a PhD student; and introduced her to many valuable contacts.

The Kokoda Track Foundation then distanced themselves from our military heritage by reducing their name to an acronym, ‘KTF’ and replacing the digger and ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angel’ logo with a blue butterfly. They now operate as Samaritans in search of a cause throughout PNG.

Dr Nelson went on to complete her PhD thesis titled, ‘The socio-economic and psychological determinants of academic outcomes in Papua New Guinea’ and has since carved out a comfortable niche for herself in PNGs aid-funded NGO sector.

The Kokoda Track Foundation then distanced themselves from our military heritage by reducing their name to an acronym, ‘KTF’ and replacing the digger and ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angel’ logo with a blue butterfly. They now operate as Samaritans in search of a cause throughout PNG.

A comprehensive report on our strategies and achievements for the Kokoda Track Foundation can be viewed on this link:

The Kokoda Track Foundation: 2003 – 2006

The Kodu Mine

The next major issue we had to confront was the appearance of survey pegs on the southern slopes of the Maguli Range and the clanking of bulldozers as they prepared to open a rich gold and copper deposit near Mt Bini on the adjacent range to the Trail.

I was able to use my political and media contacts to voice our serious concerns over the possible intrusion of mining operations on the Trail itself.

The Howard Government reacted by offering assistance to the PNG Government to stop the mine and protect the Trail from any future incursions from forestry or mining operations. It was decided that the most effective strategy would be to seek a World Heritage Listing for the Trail and the surrounding Owen Stanley Ranges.

By this time trekker numbers had increased by 255 percent from 1584 in 2004 to 5621 in 2008.

This placed an impossible strain on the CEO, Warren Bartlett, as he sought to keep an increasingly corrupt Board of Directors in check and manage an increasing number of rogue tour operators who were ignoring the need to pay for trek permits. According to an audit he arranged at a checkpoint half-way along the Trail in 2008 rogue trek operators had failed to apply for 1600 trek permits which resulted in a serious reduction in shared benefits for village communities.

The Australian Department of Environment, Water, Heritage, and Arts (DEWHA) was allocated responsibility for the Kokoda Trail as it was responsible for the heritage of ‘overseas places of interest to Australia’. A ‘Joint’ Understanding (developed and funded by Canberra) which sidelined the Department of Veterans Affairs, was signed with the PNG Government in March 2008.

The management system on the Trail at this stage was non-existent. Trek operators were desperate for some order to the system however there was no sign of any urgency from the advance DEWHA team to address this issue.

When Warren Bartlett met with one of the DEWHA officials, Troy Irwin, to express our concerns he was advised that ‘it won’t make any difference if they have to wait another year!’ Irwin was a Port Moresby based government official on a secure aid-funded salary. He had made no attempt to consult with professional trek operators to gain an insight into the reality of the Kokoda pilgrimage.

Irwin was followed by an influx of environment officials who had no previous experience with PNG, Melanesian culture, military history, pilgrimage tourism, or commercial enterprise. It was soon clear they had arrived to ‘help’ PNG to manage the environment.

There was much confusion at the time as a Kokoda Development Program was being run by the Australian High Commission and a new DFAT funded ‘Kokoda Initiative’ was assigned to the PNG Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA). They were merged years later but in the intervening period they each operated in a parallel universe to the reality of organizing and leading treks across the Trail.

In 2008 Prime Minister Rudd appointed Mr Sandy Hollway as his ‘special envoy to Kokoda’ to address increasing tensions between the Kokoda Development Program, the Kokoda Initiative, the Kokoda Track Authority, the two Provincial Governments, Local Level Government Wards, village communities and tour operators.

Hollway was a highly respected official however he knew little about PNG or the complexities and subtleties of the ‘Melanesian Way’.

I arranged a meeting to brief him on the strategy the Kokoda Track Foundation had used to engage village communities and to introduce Colonel David Knaggs with a recommendation that he be engaged as part of his team to assist in facilitating meetings and workshops with PNG stakeholders.

Knaggs had served with the PNGDF for two years during his army career, is fluent in Tok Pisin, had an empathetic understanding of PNG culture, and had trekked Kokoda. He was a former Director of Communications and Information Systems for the Australian Defence Force and worked as a consultant for Templeton-Galt where he was engaged to facilitate workshops in Port Moresby, Kokoda and Sydney for the Kokoda Track Foundation in the lead-up to the development of their strategic plan for the Kokoda Trail.

I also recommended that Sandy Lawson be engaged as part of the team. Sandy had worked in PNG as an agricultural scientist for more than 40 years, was fluent in Tok-Pisin, Motu, Koiari and Orokaiva ‘Ples Tok’. He was highly respected by traditional landowners across the Trail as he had worked with them for a couple of decades.

Neither Knaggs nor Lawson were contacted, and it was soon evident that Hollway had been engaged to provide a political fix for the Australian media rather than a management solution for PNG.

Apart from the conduct of a few forums and the official opening of an aid-funded health centre in Efogi village there were no identifiable outcomes from the forums he conducted.

We were then advised of a Kokoda Initiative plan to engage a ‘Chief Ranger’ to bring some order along the Trail.

We recommended that one of our trek leaders, Captain Reg Yates, be engaged.

Yates was well qualified for the position. He is Australia’s foremost expert in WW11 battlefields in PNG and has documented them all over a 35-year period. He authored the Australian Army Guide for Adventure Training in PNG, is fluent in Tok Pisin, and has been trekking Kokoda for more than 35 years. He is well respected by elders along the Trail and is also a highly trained paramedic and former Ambulance officer. I suggested he could train and qualify local village rangers in advanced remote area First Aid, assist with training health officers in medical clinics, prepare a detailed trail maintenance plan, conduct an audit of health centres across the Trail, and train local rangers in their traditional areas of responsibility.

He was never given the curtesy of an interview and the local Ranger system is now defunct as a result.

The Kokoda Initiative established an agreement with Queensland Parks to engage rangers on six-figure salary packages to train PNG rangers for the Trail. These rangers have no previous experience in PNG, no language skills, no knowledge of the complexities of local clan relationships across the Trail, and no understanding of the reality of the Kokoda trekking industry!

On reflection it seems the DFAT Kokoda Initiative had an unwritten policy of not engaging former military or Australian expats even though their previous experience in PNG, their qualifications, language skills, and empathy with PNG culture equips them well to give informed advice.

The two programs were eventually amalgamated, and Australian environment officials were embedded in the Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) and the Kokoda Track Authority (KTA).

The Political Conundrum

The Kokoda Trail did not rate on our political radar in the 1990s.

Early meetings were convened by the CEO of the Tourism Promotion Authority, Peter Vincent, a former Air Niugini marketing manager. Vincent understood the value of international tourism and was well placed to co-ordinate the emerging Kokoda tourism industry. He was hampered by the fact his Tourism Ministers were towards the bottom of the political pecking order due to the lack of royalty income and aid-funded projects for their portfolio. Their political ‘benefits’ were therefore limited to a few overseas trips each year – far less than their colleagues appointed to the mining, forestry, fisheries, and environment portfolios.

However, after the opening of the Isurava Memorial by Prime Ministers John Howard and Sir Michael Somare on the 60th anniversary of the battle in 2002 the number of trekkers increased rapidly along with revenue from trek permit fees.

A higher level of political interest coincided with Australia’s announcement of a $15 million annual aid-package for the Kokoda Trail in 2008.

The funds were washed through CEPA as the aid package was directed towards assisting PNG to obtain a World Heritage listing for the Kokoda Trail and nearby Owen Stanley Rangers.

In 2011, the Acting Assistant Secretary, International Heritage and Policy Branch, Mark Nizette was assigned from Canberra to Port Moresby. He took up office as an ‘management advisor’ with the DFAT funded ‘Kokoda Initiative’ in the Department of Environment and Conservation which was later rebadged as the Conservation Environment Protection Authority – see Chapter 17.

A change in Government in 2012 saw former Minister for Foreign Affairs and former Deputy Prime Minister, The Hon John Pundari MP, sworn in as Minister for Environment and Conservation.

Pundari was one of the most influential members of Prime Minister Peter O’Neill’s new government.

Since his election to the PNG Parliament in 1992 Pundari had created an extensive business empire which included more than 30 private companies. One of those, Millenium Guards, was reported as ‘employing 1,780 people in 2015 and had net assets of over K22 million’. Among Millennium’s clients were Malaysian logging giant, Rimbunan Hijau.

It is not known if Mark Nizette reported this apparent conflict of interest with DFAT or whether he turned a blind eye to it.

Soon after, Pundari appointed a ‘Ministerial Kokoda Initiative Committee’ within CEPA and appointed Nizette as secretary. This placed Nizette in an influential position as no other members of the committee had trekked across the Trail with a group of trekkers to better understand the significance of pilgrimage. His influence would also be enhanced by the knowledge that he would be involved in the approval process for aid-funded projects across the Trail in his capacity as a DFAT ‘management advisor’.

At the same time the Board of the Kokoda Track Authority appointed by the Minister for Provincial and Local Level Government Affairs withered on the vine as they did not have the expertise or the funding to execute their responsibilities regarding Kokoda tourism. They were also tainted by allegations of corruption.

In the meantime the role of the Tourism Promotion Authority was unofficially relegated to membership of Pundari’s Kokoda Initiative – their Minister was no match for the influence exercised by Pundari and Nizette.

DFAT officials ignored their responsibility to assist PNG in rationalising the legal demarcation between the Minister’s for Provincial and Local Level Government Affairs; Environment, Conservation and Climate Change; and Tourism, Arts and Culture regarding pilgrimage tourism across the Kokoda Trail.

The result has been a 46 percent fall in pilgrimage tourism since DEWHA officials assumed responsibility for the Kokoda Trail in 2009.

The significance of ‘military heritage’ across the Trail was further reduced when DEWHA was rebadged as the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC) – ‘Heritage’ was removed from the title and the First Assistant Secretary we had been dealing with, James Shelvin, moved on.

Under DEWHA/DPEWPC management the KTA enjoyed a 10-fold increase in staff and a multi-million dollar budget via the DFAT Kokoda Initiative to manage Kokoda tourism. But rather than getting out onto the Trail with professional trek operators to gain an understanding of trekkers aspirations and the needs of guides, carriers, campsite owners and villagers they chose to lock themselves within their Port Moresby offices and conduct meetings and forums to ‘build capacity’, develop ‘mentoring programs’, look at ‘gender equity’ issues, and follow the dictates of Canberra regarding ill-conceived ‘village livelihoods’ type projects.

The needs of the pioneering trek operators for basic management systems to support villagers to develop campsites, to allow operators to book them in advance, to manage trek itineraries, to maintain the Trail, to introduce micro-business initiatives for landowners, and to identify, restore and interpret historic battlesites were ignored.

The law of the jungle therefore continued to prevail which resulted in bitter disputes along the Trail as different trek groups with a combined total of up to 50-60 trekkers would arrive at a campsite with a capacity for 15-20! Some rogue trek groups did not supply enough meals for their trekkers and PNG guides. Others did not have any trained medical staff or communications equipment which resulted in a couple of preventable deaths.

These experiences led to negative publicity and a serious decline in trekker numbers under the new Kokoda Initiative-CEPA-KTA regime.

In 2012 the Australian management contingent transferred responsibility for managing Kokoda tourism to their PNG counterparts who had no business management qualifications or experience. They had not received any management training and were not even left with a database management program to help them run the operation.

All they inherited was a glossy ‘Kokoda Track Strategic Plan: 2012-2015’. It was no surprise that not one of the five key strategies or 33 objectives was achieved during that period.

Their plan has since been quietly shelved and no attempt has been made to revisit the topic since then.

World Heritage Listing FAIL

The 2009 Joint Understanding sought to ensure ‘the World Heritage values of the Kokoda Track and Owen Stanley Ranges are understood and, where appropriate, protected’ – a key feature of the Joint Understanding related to the Brown River catchment which was identified as ‘a future water and power supply opportunity for Port Moresby.’

DEWHA officials were therefore dispatched to PNG to assist in implementing their objectives within the Joint Understanding.

While they were engaging consultants, facilitating meetings, organising forums and conducting workshops a Chinese investor built a $280 million dam on the Brown River as part of the Edevu Hydro Power Project – this effectively solved the problem identified in the Joint Understanding.

Then in 2015 an expert report from the late Dr. Peter Hitchcock and Dr. Jennifer Gabriel revealed that the Kokoda Trail did not meet the criteria for a World Heritage listing.

Rather than refocus on military heritage Australian environment officials within the DFAT Kokoda initiative scrambled to realign their strategy towards establishing an ‘Interim Protection Zone’ to have it declared as a ‘protected area’.

This was motivated by the need to protect their own aid-funded careers as an earlier RAPPAM report that the Kokoda Trail faced a low degree of environmental threat while offering an opportunity of an income stream for village communities.

Decline in Trekker Numbers

Since the Australian Government assumed responsibility for the Kokoda Trail in 2009 under the terms of the Joint Understanding signed in 2008, the number of Australians trekking across it has almost halved – see Chapter 28 and 32.

The primary reason for the fall is the Kokoda Initiative-CEPA focus on social-environment issues rather than assisting PNG to manage their most popular tourism destination as a tourism enterprise for the economic benefit of traditional landowner communities.

Increase in Illegal Trek Operators

According to PNG Investment Promotion Authority (IPA) records, Adventure Kokoda Pty Ltd, is the only Australian Kokoda tour company to have fully complied with their IPA Act.

Compliance costs and taxation obligations have placed the company at a serious financial disadvantage compared to those who do not comply.

Kokoda Initiative-CEPA-KTA have turned a blind eye to the proliferation of illegal Kokoda tour companies who flout their law. The KTA has continued to issue licenses in breach of their own ‘Kokoda Tour Operators Conditions 2012’.

Illegal tour operators have therefore been easily able to avoid their taxation obligations in PNG.

Unlawful Cancellation of Adventure Kokoda Tour Operator’s Licence

Our attempts to address the inept management of Kokoda tourism since the Acting CEO, Julius Wargari, was appointed five years ago led to the cancellation of our Adventure Kokoda tour operators license by the Minister for Environment, Conservation and Climate Change on 26 April 2023.

Wargari was seconded to the Kokoda Track Authority in an Acting capacity from the Department of Provincial and Local Level Government Affairs to manage Kokoda tourism in November 2018.

He had no commercial business qualifications and no previous experience in tourism, trekking or pilgrimage. He has remained in the role in an Acting capacity for five years despite an assurance from Minister Pundari that a ‘permanent replacement would be recruited following the review into the KTA’.

Since then the Minister has moved on.

The KTA Review was published on 4 July 2018 but no action has since been taken to appoint a permanent CEO with business management qualifications.

As a result Mr. Wargari has remained in a position he is completely unqualified for.

Since then we have sighted an opinion from the PNG Solicitor General that his appointment is invalid. It is certainly doubtful that his reappointment would have been approved by the National Executive Council every three months as is required by the Public Service Act.

The process leading to the cancellation of our license took their ineptness to a new level:

- The Minister does not have any legal jurisdiction over the management of the Kokoda Trail – this rests with the Minister for Provincial and Local Level Government Affairs.

- The Acting CEO who advised the Minister’s ‘Kokoda Initiative Committee’ to cancel our license for our alleged non-payment of trek permit fees was paid in full for all our Anzac treks on 15 and 16 April 2023 – his office staff issued receipts for all payments on 17 April 2023. Payment and receipt details are included on this link: Adventure Kokoda Tour Operators License Update.

- The payments were in accordance with the Koiari and Kokoda Track Local-Level Government Trek Permit Laws 2005.

- Sometime during the following week Mr. Wargari advised the Minister’s Kokoda Initiative Committee that we had not paid for our trek permit fees despite having possession of the four cheques we presented to him.

- For reasons unknown, the Acting CEO did not present the cheques to the bank for deposit for a further two months – on 13 June 2023.

On 14 December 2023 the PNG National Court found that the Minister’s decision to cancel our licence was unlawful and granted costs to Adventure Kokoda.

This should be the catalyst for a change in the management structure for Kokoda tourism and the sacking of those officials who were a party to the attempt to put Adventure Kokoda out of business.

The Future

PNG now has a choice. It can continue to run the Kokoda Trail as an aid-funded environmental experiment with a Third-World management system that provides short term benefits for a few – or it can seek to realize its potential as a world-class pilgrimage tourism destination for the economic benefit of the people who own the land across it.

Should it choose to realize its potential it will be necessary to run it as a commercial tourism enterprise.

A proposed organizational structure for such a management system is outlined in Chapter 38.

Conclusion

When I first trekked Kokoda in 1991 local villagers across the Trail earned zero income as only a small number of Australians trekked across it each year.

Trek groups carried their own dehydrated food and usually engaged a couple of local guides to support them. There was no organization in place to manage it; no fees were payable; and there was no economic benefit for subsistence villagers.

Since then, more than 56,000 Australians from all walks of life have trekked across it.

Research has revealed they are motivated by the military heritage of the Trail along with the physical and emotional challenge it presents. It is a unique pilgrimage in this regard.

This has generated approximately $250 million (K570 million) in tourism revenue for PNG airlines, hotels, transport, supermarkets, camping stores, employment of guides and carriers, campsite owners and villages. wages, campsite fees and local services.

Kokoda trek operators have paid more than $5 million (K12 million) in trek fees to the PNG Kokoda Track (Special Purpose) Authority (KTA).

Philanthropic donations of trekkers personal clothing, boots, medical and school supplies along with camping gear would amount to a further $5 million (K12 million) in hidden benefits. For example, when trekking began in 1992 none of the guides or carriers owned a pair of boots – today they all have high value trekking boots valued at up to $450 (K1000) a pair which have been donated to them.

The value of positive publicity for PNG from television documentaries, newspaper articles, and social media reports would be tens of millions of dollars.

However, since the Australian Government assumed responsibility for the management of the Kokoda Trail via the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative, the PNG Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA), and the Kokoda Track (Special Purpose) Authority in 2009, trekker numbers have fallen by 46%.

This has resulted in a cumulative loss in the region of $20 million (K46 million) in foregone wages, campsite fees and local purchase for subsistence villagers across the Trail.

The fall in trekker numbers is primarily because the DFAT Kokoda Initiative and CEPA have failed to invest in any military heritage sites to enhance the value of the pilgrimage for international tourists since they assumed responsibility for it in 2009.

They have also failed to introduce any management protocols for Kokoda tourism. The ‘law of the jungle’ prevails along the Trail as trek groups have heated clashes over campsites that do not have the capacity to meet demand.

After two decades in charge it is still not possible to book a campsite; there is no trek itinerary management system in place for groups; sections of the Trail remain dangerously unsafe; and there are no toilets which meet the most basic hygiene standards.

Local villagers have been disenfranchised as no micro-business programs have been introduced to assist them to earn additional income by meeting the needs of trekkers.

Covid provided an opportunity for the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative, CEPA and the PNG Tourism Promotion Authority (TPA) to review the reasons behind the rise and fall of Kokoda tourism under their watch since 2009.

The engagement of anthropologists, archaeologists and environmentalists to search for ‘objects’ across the trail has no relevance to the development of a pilgrimage tourism industry.

The failure to engage an accredited Australian Military Heritage Architect to develop a Military Heritage Master Plan for the Kokoda Trail continues to limit its potential as a World Class pilgrimage tourism destination for international trekkers.

The failure to develop a database of trekkers has severely limited the opportunity to raise a significant amount of money each year for charitable causes in Central and Oro Province.

The failure to train local villagers to earn additional income from trekkers through the provision of services to meet their needs has deprived them of their rightful share of benefits from Kokoda tourism.

The failure to develop a Trek Itinerary Management System and a Campsite Booking System has limited the income earning opportunities for villagers along the trail as they have no idea who is arriving, or when, and are therefore unable to prepare goods and services to meet their needs and earn additional income..

The failure to protect the welfare of PNG guides and carriers engaged by illegal Kokoda tour operators is a serious breach of the Kokoda Track Authority’s ‘Duty of Care’ towards the people they are supposed to support and trek.

Recommendations

- Government acknowledge that the primary reason Australians choose to trek across the Kokoda Trail is related to the military history of the Kokoda campaign;

- Australia rebadge the ‘Kokoda Initiative’ within the PNG Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) as the ‘Owen Stanley Ranges Initiative’ to reflect its role in environmental ‘Protected Area Management;

- Australia and PNG establish a Joint Agreement for Military Heritage;

- The lead agencies for the Joint Agreement for Military Heritage to be the Department of Veterans Affairs and the PNG Tourism Promotion Authority TPA);

- The physical boundaries of the Kokoda Initiative be redefined to include the Kokoda Trail between Sogeri and Kokoda, and the Kokoda Highway between Kokoda-Popondetta-Buna- Gona-Sanananda.

- Australian provide funding for the following:

- Development of a Joint Agreement for Military Heritage;

- Development of a Military Heritage Master Plan for the Kokoda Trail;

- Four (4) key management positions for the redefined Kokoda Initiative for a period of five (5) years;

- Management systems for Kokoda Tourism (website, database, accounting, booking systems, trek itinerary management, Trail maintenance, campsite development, and village-based workshops.