On the 75th anniversary of the Gallipoli campaign Prime Minister Bob Hawke allocated $10 million to lead a group of 52 veterans and their carers back to Anzac Cove to commemorate the occasion.

25 years later, Prime Minister Tony Abbott allocated $100 million for a Sir John Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux to honour the Centenary of Anzac.

On the 75th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull chose not to attend the Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery, and DVA did not make any provision to support veterans who wished to return and pay a final tribute to those they left behind.

On the 80th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign nothing was spent on any military heritage site across the Trail to commemorate the service and sacrifice of our Kokoda veterans.

Lest We Forget Indeed!

Australia’s interest in the Kokoda Trail lay dormant for 50 years after the war.

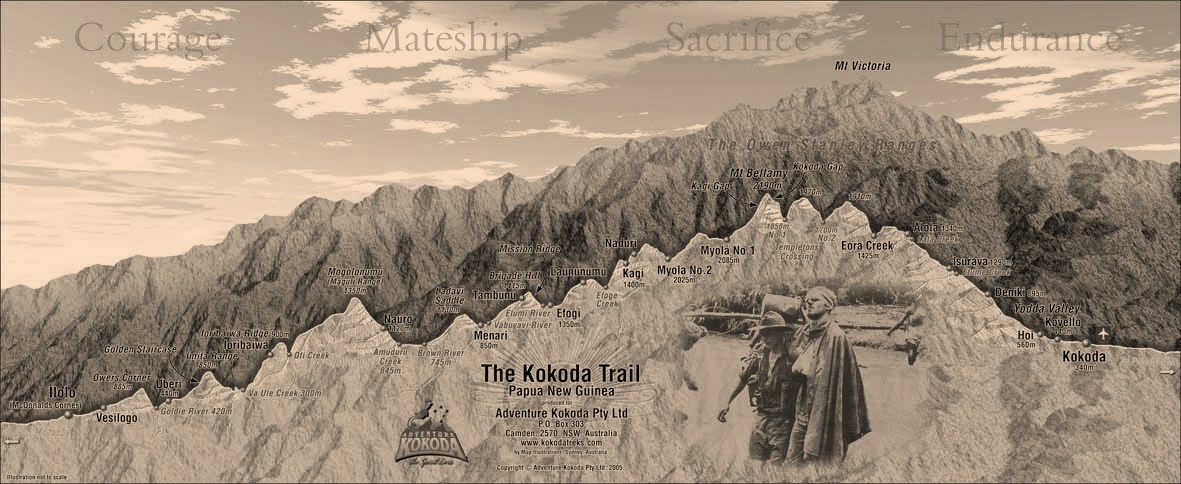

The few hardy trekkers who crossed it each year since 1942 were witness to our apathy towards our wartime heritage as there was not one official memorial along the 138 km Trail to commemorate the Kokoda campaign.

Awareness increased after Paul Keating became the first Prime Minister to visit Kokoda to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the campaign in 1992.

It was reinforced with the opening of a significant memorial at Isurava by Prime Ministers’ John Howard and Sir Michael Somare a decade later for the 60th anniversary.

In 2006, a proposal by Frontier Resources to mine the southern section of the trail after the discovery of a $3 billion gold and copper deposit caused the Australian Government to develop a ‘Joint’ Understanding[i] with a $14.9 million commitment to:

‘assist the PNG Government in its efforts to improve the livelihoods of local communities along the Track and to establish effective management arrangements so that the Track is protected and delivers increasing benefits to local people. Those funds will also be used to conduct a feasibility study into a World Heritage nomination’[ii].

Responsibility for the agreement was delegated to the Department of Environment, Water. Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) due to their responsibility for overseas sites of historic interest. ‘Heritage’ was later removed from their title when it was rebadged as the Department of Sustainability Environment Water Population and Communities (DSEWPC).

The Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA), which is responsible for commemoration, was not included in the drafting of the Joint Understanding!

It was soon apparent that DEWHA officials dispatched to PNG to help ‘save’ the Kokoda Trail had little understanding of pilgrimage tourism, lacked expertise in commercial management practices, and were unfamiliar with the Melanesian Way[iii]’.

As a result, the emergence of a multi-million-dollar Kokoda Tourism Industry since Prime Minister Paul Keating’s visit has since fallen by 42 percent. The cumulative loss for subsistence villagers along the trail since then is in the region of $19 million in foregone wages, campsite fees and local purchases – and these were the people we have spent some $65 million trying to help!

In retrospect the Joint Understanding was a hasty response to a mining threat on the Trail.

At the time AusAID was responsible for the delivery of aid projects in PNG. A ‘Kokoda Development Program’ was then patched onto the responsibilities of the Australian High Commission in Port Moresby.

The KTA was legally responsible to the Minister for Provincial and Local Level Government however PNG Tourism assumed an active role in the Trail at the time as it was emerging as PNGs most popular tourism destination.

For some inexplicable reason, the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA), which is responsible for ‘commemorating the service and sacrifice of all those who served Australia and its allies in wars, conflicts and peace operations through commemorations, memorials, war graves and research . . . in Australia and overseas’[iv] was excluded from anything to do with the development of a plan to commemorate our shared wartime heritage across the Trail.

This led to a nonsensical situation where DVA was responsible for our WW1 heritage at Gallipoli, while DSEWPC was responsible for our WW II heritage at Kokoda.

For several years, the KDP and the KTA operated at odds with each other as they worked on separate projects, issues and agendas across the Trail.

A former Australian Assistant Secretary for International Heritage at the rebadged Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC) in Canberra was assigned as a ‘Management Advisor’ to CEPA in August 2011.

Soon after, a ‘Kokoda Initiative’ was added to the mix and embedded within the PNG Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) which was responsible to the Minister for Environment and Conservation.

CEPA then assumed responsibility for the KTA in the management of the emerging Kokoda tourism industry in addition to its responsibilities for its oversight of their existing six Acts of Parliament relating to the environment. i.e., the Mining Act; the Oil and Gas Act; the Forestry Act, The Fauna (Protection and Control) Act; The Conservation Areas Act; and The National Parks Act.

The resultant dysfunction caused the PNG Minister for Environment and Conservation to establish a ‘Ministerial oversight committee’ within CEPA which was responsible for the World Heritage aspects of the Joint Agreement.

None of the members of the oversight committee had ever trekked across the Kokoda Trail and none had any previous experience in business management or pilgrimage tourism – apart from the Management Advisor who had trekked with a small eco-trekking company in 2004. He was appointed Secretary to the committee and his title was upgraded to ‘Strategic Management Advisor’. This effectively meant that responsibility for Kokoda pilgrimage tourism was subtly transferred from the Minister for Provincial and Local Level Government to the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative within CEPA.

The PNG Minister for Tourism, Arts and Culture, who should have responsibility for the Trail in accordance with his Ministerial charter and because it is the nation’s most popular tourism destination, was excluded from the chain of command even though his department is listed as having responsibility for the KTA on the current KTA website.

Around this time a bitter dispute erupted between the DFAT Strategic Management Advisor and the PNG CEO of the KTA.

This led to the Strategic Management Advisor being declared persona non-grata in the KTA office. The reverberations of the dispute were felt along the trail and led to threats to close it because the PNG CEO of the KTA was also a ‘wan-tok’ landowner.

In 2014 the Kokoda Initiative commissioned an ‘Interim Review of the Second Joint Understanding’.

The report was leaked by the PNG CEO of the KTA to inform Kokoda trek operators of the impossible situation his office faced in meeting the demands of ill-informed Australian officials from DSEWPC while trying to meet the needs of trekkers, trek operators and his people along the Trail. A review of the document confirmed the PNG CEOs concerns.

It was evident that the management system imposed on the KTA had failed and the DFAT- Kokoda Initiative was operating in a parallel universe without any empathetic understanding of the reality of the Kokoda Tourism Industry. For example, none of the 5 key strategies or 33 objectives contained in their KTA Strategic Plan: 2012-2015 (developed without consultation with trek operators or landowners) was achieved. It was then quietly shelved and has not been replaced.

A DFAT-Kokoda Initiative Master Plan, published on 15 August 2016, ignored the significance of pilgrimage tourism despite the fact that this is the primary reason the Kokoda Trail has become such an important destination for the 54,623 Australians who have trekked across it over the past 16 years. A Preliminary review of the Master Plan was submitted, and ignored.

The Master Plan also ignored landowners along the trail. As a result, they remain suspicious of it because they were not consulted, and no village-based workshops were conducted to discuss it. They believe they were deliberately excluded from the process as meetings were held in locations that were difficult for most of them to access and the so-called ‘village representatives’ who live in Port Moresby were carefully chosen.

According to the Australian consulting company, Trip Consultants, their Master Plan addressed the ‘medium and long-term development priorities which support the identified KI Vision and Goals and highlights key roles and institutional requirements for support implementation’.

For those closely associated with Kokoda tourism, local landowners and their subsistence communities along the trail are more interested in the short term as per Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – particularly regarding their daily need for food, medicine, access to schools and the opportunity to earn some money.

It would therefore be a mistake to assume that traditional owners concur with the Kokoda Initiative Master Plan which is incomprehensible to them and irrelevant to their current short-term needs – and to the needs of the paying customers who sustain the industry.

In early 2016 a Ministerial reshuffle coincided with the transfer of responsibility for Australian aid projects from AusAID to DFAT. This had no impact on the modus operandi of the Kokoda Initiative as the same environment officials put in place by DSEWPC were simply transferred to DFAT. However, their influence was increased with the amalgamation of the KDP and the Kokoda Initiative.

The PNG Minister for Environment and Conservation was one of the most astute and influential MPs in Parliament. During his time as an MP, he developed an extensive business portfolio which would have detracted from his ability to focus on the detail of his portfolio.

He was further burdened with the addition of a ‘Climate Change Authority’ Act to his portfolio, which was then rebadged as Environment, Conservation and Climate Change, and required his attendance at numerous aid-funded international forums on the topic.

It is not known if DFAT funded the PNG Ministers attendance at these international forums or if his DFAT Strategic Advisor accompanied him. What is known is that the effective management of the Kokoda tourism industry continued to decline under their watch.

In 2017 former Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill, became aware of the dysfunction of the management system along the Trail and ordered a review of the Kokoda Track Authority.

Around the same time a KTA Board Meeting was convened to resolve the standoff between the DFAT Strategic Advisor and the PNG CEO of the KTA. This resulted in an announcement of the CEOs intention to resign.

Neither the PNG CEO nor several of his wan-toks attended the meeting.

The following day the KTA Board was reconvened by the PNG CEO with his wan-toks in attendance – the decision of the Board meeting the day before was overturned, and the CEO retained his position.

Behind the scenes negotiations continued and soon after the CEO accepted a lateral ‘promotion’ as a tourism executive with the National Capital District Commission (NCDC) in Port Moresby.

He was replaced by the Deputy Secretary of the Department of Provincial and Local Level Government. Mr Julius Wargirai in an acting capacity until the KTA Review, ordered by former Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, had run its course. Mr Wargirai is an experienced PNG bureaucrat but has no experience in business, pilgrimage tourism, or trekking.

The DFAT Strategic Advisor was embedded back into the KTA office soon after Mr. Wargirai’s appointment as Acting CEO.

Kokoda tour companies were taken by surprise when they learned that one of the first actions of the Acting CEO was to ‘donate’ K350,000 of their Trek Permit Fees to an Australian NGO, supposedly to distribute as ‘educational supplements to villagers along the Kokoda Trail and beyond’.

This accounted for a large slice of the K1.1 million the KTA received for Trek Permit Fees in 2018.

There was no consultation and there does not appear to be any record of KTA Board approval for the ‘donation’. The approval contravenes KTA rules re the disbursement of trek fee income and exceeded the authority of a CEO appointed in an acting capacity.

This is particularly galling for Kokoda tour companies who have been calling for the Kokoda Initiative and the KTA to invest in hygienic toilets and campsite management to meet the needs of their paying customers for many years.

Kokoda trek operators must also deal with the increasing frustrations of communities along the Trail who do not believe they are receiving their fair share of benefits from the Kokoda Tourism Industry.

The refusal of the Kokoda Initiative-KTA to publish annual financial reports to account for the disbursement of trek fee income adds to these frustrations. They now seem to operate as an unaccountable law unto themselves.

A chronology of the management outcomes since the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative assumed responsibility for the Kokoda Trail is outlined on this link.

Poor governance practices that would not escape scrutiny in Australia now seem to be normal practice in the DFAT funded Kokoda Initiative in PNG.

Australian officials quickly learned their PNG counterparts will agree to any proposal that has an Australian Aid dollar attached to it. This allows them to deflect criticism of their inevitable failures by responding with the cliche ‘this is what PNG wants!’.

The outcome of the management system imposed on the Kokoda Trail by DSWEPC-DFAT officials since 2009 is reflected in the data.

Trekker numbers have declined by 42% under their watch. This translates into a cumulative loss of $19 million (K46 million) for the subsistence villages across the Trail in foregone wages, campsite fees and local purchases – and these are the people we have spent more than $50 million (K150 million) trying to help!

During this time, DFAT-DVA have failed to invest any funds in the development of significant military heritage sites to enhance the value of the pilgrimage or any funds in campsite development or hygienic toilets.

As a result, the Kokoda Trail has been prevented from reaching its potential as a World class pilgrimage tourism destination.

This will not be resolved until we find out why the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative has:

- Failed to ensure staff employed by the KTA have professional management qualifications and previous commercial management experience?

- Failed to ensure the KTA publishes regular financial reports to account for the Trek Permit Fees and other Government funding it receives?

- Failed to develop a database management system?

- Failed to implement a ‘Tour Operator License System’ that ensures compliance with the PNG Investment Promotion Authority (IPA) Act?

- Failed to develop a ‘Campsite Booking System’ to enable Kokoda tour operators to secure campsites for groups they lead across the Trail?

- Failed to identify sites for camps along the length of the Trail to meet the demands of trek itineraries during peak trekking periods i.e., Anzac and school holidays?

- Failed to develop a standard campsite plan (dining hut, kitchen, drying hut, sleeping accommodation for PNG support crews, hygienic ablution facilities, etc) to meet the needs of various group sizes at each strategic location?

- Failed to provide any micro-finance support or training to assist campsite owners to develop individual sites to meet the needs of trek groups?

- Failed to develop a proper certification program for each campsite?

- Failed to develop a ‘Trek Itinerary Management’ system to ensure the integrity of a ‘Campsite Booking System’?

- Failed to implement a ‘Campsite Audit Program’ to ensure campsite owners are paid the full amount due from each trek group?

- Failed to build hygienic toilets for their paying customers anywhere across the Trail?

- Failed to develop and implement an ‘Environmental Management Program across the Trail?

- Failed to identify the names of landowners across the Trail?

- Failed to conduct professionally facilitated village-based annual workshops to identify the basic and future needs of village communities?

- Failed to provide regular employment for villagers in a ‘Trail Maintenance Program’ to keep the Trail clear and safe?

- Failed to develop a registration system and logbook for individual guides and carriers?

- Failed to protect the welfare of guides and carriers by limiting the weight they are authorised to carry to 18 kg (the maximum allowed during the Kokoda campaign); ensuring they are provided with a full trek uniform; a sleeping bag and mat; a minimum daily rate of pay of K70; a day’s bonus payment at the end of each trek; a K250 ‘Walk Home Allowance’; and a minimum of 8-days pay for treks of a shorter duration as they have to work longer hours to cover the same length of the Trail.

- Failed to invest in any military sites across the Trail to enhance the value of the pilgrimage for their paying customers?

- Failed to invest in any environmental signage across the Trail to identify trees, plants and geographical features?

- Failed to obtain indigenous names of geographic features, rivers and creeks across the Trail’.

Until these questions are addressed, and the PNG Government reclaims ownership of the resource, the potential of their most popular tourism destination will never be realised.

[i] The ‘Joint’ Understanding led to a dramatic increase in the number of Australian bureaucrats and consultants. The ‘Kokoda Trail’ was redefined as the ‘Kokoda Corridor’ and its boundaries were extended to include Sirinumu Dam and the beach-head areas of Buna, Gona and beyond. The re-definition created a smorgasbord of opportunity for Canberra based environmentalists, anthropologists, archaeologists and social engineers. A review of reports commissioned by the Australian Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC) since 2008 will verify this fact. A review of their outcomes will also reveal their many failures – for example they have conducted ‘Social Mapping’ exercises across the trail but cannot identify any current landowners; their $1.5 million ’Village Livelihoods Program – developed without any consultation with PNG authorities or landowners – did not produce a single dollar in added value for local villagers along the trail; nor have they developed a list of indigenous names for the geographic features, creeks and rivers across the trail.

[ii] PNG and Australia Agree Action on Kokoda. Media Release issue The Hon Peter Garrett, Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts in Madang on 23 April 2008

[iii] In 2018 PNG was classified as the most corrupt country in APEC

[iv] https://www.dva.gov.au/commemorations-memorials-and-war-graves

We really need more Australians to recognize the issues with this, and express outrage at our Government in order to get a positive result for the people in PNG that are making every effort to enable a continuing process of Kokoda Trail access, and appreciation, by any visitors that wish to pay their respects to the fallen in this field. Most Australian people are aware of the issues that confronted our Servicemen when they transitioned the Trail all those years ago, and also the aid provided by local Papua New Guinean people. What those same Australians may not be aware of, is that the funding for support of Kokoda Trail facilities/amenities and general compensation for local participants has all but dried up now. We all need to get hold of our nearest Politician in Australia, and shake some sense into the buggers, and election time might just be an ideal opportunity for us all. I live in FNQ, and will certainly be making my opinion/demands well known to the local pollies, in this regard, for starters. and with the benefit of email and social media, I will also be extending my concerns on those channels/paths.

Huge piece of work Charlie to piece together the administrative management of the Kokoda Trail.

l have know a few of the advisers on the DFAT funded Kokoda Initiative program over the years (from Coffey, than Abt Associates) and they have certainly been devoted and willing. One had a science background, and the other just happened to be in PNG and had worked for NGOs in management. They had no particular interest in the solemn ground of Kokoda. Their DFAT managers are generally nice young kids with socialist ideologies, around whom its fine to have a beer, but one was also frightful of being a conservative or too patriotic.