The Rise, Fall and Future of Kokoda Tourism

The rise in Kokoda tourism can be traced to former Prime Minister, Paul Keating spontaneously dropping to his knees and kissing the ground at Kokoda on the 50th anniversary of the campaign in 1992.

Keating’s gesture, and his epic speech, led to the development of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between PNG and Australia[1] regarding the significance of our shared military heritage.

It culminated in the opening of a landmark memorial at the Isurava battlesite 10 years later (on the 60th anniversary of the battle) by his successor, Prime Minister John Howard and PNGs Grand Chief and Prime Minister, Sir Michael Somare.

The subsequent fall in Kokoda tourism has its roots in the discovery of the $8 billion Kodu goldmine at Mt Bini, adjacent to the Kokoda Trail four years later in 2006.

The discovery precipitated a panic reaction from the Australian Government who, since the opening of the Isurava Memorial, had remained largely ambivalent towards the historic Kokoda Trail.

A public backlash against images of bulldozers carving roads out of virgin jungle adjacent to the Trail and the subsequent pollution of the pristine Ofi Creek which crossed it, snapped them out of their stupor.

While they were asleep at the wheel a mining company, Frontier Resources, had negotiated the necessary approvals for the mine with the PNG Government and landowners at Nauro village.

Nauro was the epitome of a subsistence village. It had been relocated from its wartime location in the Nauro swamp after rumours of sorcery related differences led to half the village moving up to a spur on the southern side of the Maguli Range and the other half moving to a valley between the range and Mt Kodu.

The villagers were destined to a subsistence future as they had never received any assistance from Government.

Their first opportunity to earn some money came with the increase in the number of trekkers passing through their village after the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 1992. Their strategic position created an opportunity for a few basic campsites which charged K20 per trekker.

However, the operation of a goldmine on their land offered them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to break from the shackles of subsistence living so it was an attractive proposition for them.

In their haste to get on with the job of mining Frontier Resources neglected to consult with the growing number of Kokoda tour companies to allay any fears they might have regarding the environmental protection of the historic wartime Trail.

This led to the backlash which triggered the Australian Government to finally take an interest in the area.

Unfortunately they also failed to consult with Kokoda tour operators in their endeavour to manage the crisis and being seen to fix the problem.

The approval process for the mine was then challenged by both Governments which resulted in Frontier Resources and local landowners ramping up a local campaign with threats to close the Trail.

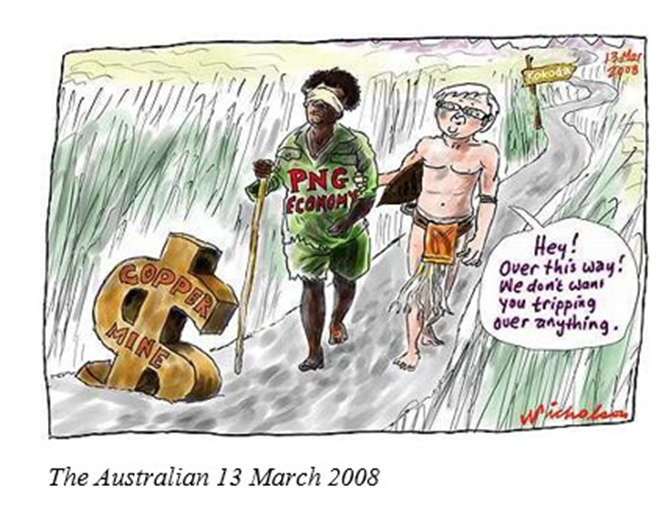

They argued that the stoppage of the mine would see the Koiari people along the Trail regarded as ‘cultural zoo’ exhibits – local villagers said they did not want to be porters for foreign companies for the rest of their lives, and that Australian tour companies were the main beneficiaries of Kokoda tourism.

They also argued that Australia’s involvement violated Papua New Guinea’s sovereignty[2]

In the meantime the proposed mine had the support of the PNG Chamber of Mines and Petroleum, the president of the Koiari Local Level Government, the Governor of Central Province, and the Vice-Minister for Mining.

The limitations of the PNG Kokoda Track Authority (KTA) were also exposed as the PNG CEO struggled with a lack of financial support from the Oro and Central Provincial Governments and an ambivalent Australian Government. He also had to deal with increasing corruption among his Board of Directors who were more intent on siphoning money from the KTA to themselves and their wan-toks than in the long-term development of Kokoda tourism.

Frontier Resources initially offered 5% equity and compensation to the landowners as an inducement for their approval. They later upped the ante by proposing that Frontier Resources would give up 2%. Of their equity if the Nauro landowners give up 1% of theirs. This offer would leave the landowners with 4% with a return on 3% to be paid to the KTA who would be required to invest half of the funds for the preservation of the Trail and half for education for communities across the Trail.[3]

Newspaper reports estimated the return for landowners and the KTA over the estimated 10-year production of the mine would be in the vicinity of $100 million (K234 million).

Frontier Resources claimed the economic benefits for just one mine would provide more in taxes and royalties to the Papua New Guinea government than all Australian aid and provided the example of the expected royalties and taxes from Ok Tedi in 2007/08 (Media Release, 19 November 2007)[4].

In October 2007, the Minister for Environment, Malcolm Turnbull MP, reacted to the proposed mine with an announcement that Australia would provide $16 million (K38 million) to assist PNG to secure a world heritage listing. His successor in the Rudd Labor government, Peter Garrett, confirmed the provision of the money and announced he was ‘fast tracking’ the world heritage application.

At the same time Frontier Resources approval for the mine was successfully challenged on a technicality by both governments.

The Rudd Labor government’s intervention was therefore seen to have ‘saved’ the Kokoda Trail and they immediately set about assisting PNG to obtain a World Heritage listing through the signing of a joint agreement in Madang on 23 April 2008.

Nauro landowners reportedly received a generous compensation package from the PNG Government and have since mostly abandoned their village and moved to Port Moresby.

The joint agreement led to an influx of Australian environment officials, academics, anthropologists, archaeologists, and social engineers which was reminiscent of Keith Wiley’s observation in his 1965 book ‘Assignment New Guinea’:

‘In recent years the academics have discovered New Guinea. Grave, plump, portentous, they swarm north in their hundreds each winter, generally finishing somewhere near Goroka in the Eastern Highlands where at times they become so numerous that every bush and stone seems to conceal a lurking bureaucrat or anthropologist. After a few weeks or a few months they return home to prepare brisk solutions for all the problems which beset the land. Too often they see New Guinea coldly as an exercise in nation-building to be carried out as quickly as possible, with one eye on the taxpayer at home and the other on some ranting demagogue in the United Nations.

‘At times the maligned colonialists, who walked ever the country and fought for it, seem to come nearer the heart of the matter. Stripped of slogans and self-interest, New Guinea emerges not as a ‘problem’; to be ‘solved’, or assessed , but simply as a land, wild and beautiful, worthy to be loved for its own sake; with a people, backward, kindly, and in need of help’[i].

The new arrivals were just as unfamiliar with PNG and the Melanesian Way!

Many proceeded to trek across it once with a local guide then settled into the ‘Kokoda Development Program’ within the Australian High Commission and the offices of the PNG Conservation Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) in their quest to seek a World Heritage listing which would prevent any further mining or logging incursions into the area.

They were obviously unaware of, or ignored, the findings of an earlier 2006 ‘Rapid Assessment and Prioritisation of Protected Area Management’ (RAPPAM) report for PNG, compiled by the Department of Environment and Conservation, the PNG Forestry Authority, the Research and Conservation Foundation, the Nature Conservancy, and the Village Development Trust which advised that:

‘Many of the areas withhigh socio-economic importance are facing a relatively low degree of threat (Kokoda, Wiad, Pirung).

‘Areas like Lihir, Tonda, and Bagiai are exceptions to this rule and hence require more efforts to protect them from the variety of threats they are currently facing.’

Another group of Canberra officials moved into the offices of the KTA and assumed responsibility for the management of the Kokoda Trail.

None had any previous experience in PNG or had ever trekked across the Trail with a professional tour company to understand the impact of the pilgrimage on their paying customers.

They also failed to conduct any village-based workshops to seek to understand local community needs.

Of more concern was the fact that they were not much interested in advice from tour operators who had been leading treks across the Trail over the previous 15 years and disregarded reports sent to them in good faith.

Since they assumed responsibility for the Trail no management systems have ever been introduced; no investment has been made in wartime heritage sites to enhance the value of the pilgrimage for trekkers; no investment has been made in ensuring campsites are adequate to meet the needs of trekkers; no initiatives have been introduced to assist subsistence village communities to earn additional income by providing goods and services that meet the needs of trekkers and there is no evidence of any plan to maintain and protect the environment across the Trail.

The results of their failure to properly manage Kokoda tourism since they took control in 2009 are a matter of record. Kokoda trekker numbers have fallen by 46 percent. This has led to a cumulative loss of some $19 million (K45 million) in foregone wages, campsite fees and local purchases for the subsistence village communities across the Trail.

The failure can be attributed to the Australian government’s emphasis on managing the Trail as an environmental resource to obtain a World Heritage listing.

In 2015, an expert report by the late Dr Peter Hitchcock, Dr Jennifer Gabriel, and Dr Matthew Leavesley concluded that the Kokoda Trail does not meet the criteria for a World Heritage listing.

Since then Australian environment officials have switched their strategy towards seeking ‘protected area status’ and have sought to maintain their control over the Trail via a clandestine attempt to establish a new ‘Kokoda Track Management Authority’ within CEPA – see Chapter 34.

Once again, Australian Government officials failed to consult with the two key stakeholders in Kokoda tourism in the drafting process, i.e., Kokoda Tour Operators who generate the income for the industry and the villagers who own the land sacred to our shared military heritage.

They also continued to ignore the findings of the RAPPAM report and diverted their environmental resources to areas that have already been identified with high-risk threats.

Kokoda tourism has therefore failed to meet the economic expectations created by the Australian Government in 2008 for village communities.

In retrospect, village communities would have been far better off under the proposals put forward by Frontier Resources, and trekker numbers would have continued to grow if Kokoda tourism had been professionally managed as a commercial tourism enterprise for the economic benefit of the traditional landowner communities across the Trail.

Mt Kodu mining site on the range adhacent to the Kokoda Trail on the Magulir Range

Telrphoto of the Frontier Resources mining site at Mt Kodu taken from the Kokoda Trail on the Maguli Range

Adventure Kokoda guide on the Maguli Range observing bulldozers building a road to the Mt. Kodu mine on the adjacent range in 1997

Telephoto of bulldozer ripping out an access road to the Mt Kodo goldmine

Village welcome for Kokoda trekkers

LINKS FOR FURTHER READING:

- State Society and Governance in Melanesia ANU Briefing Note No 4 2008 by Hank Nelson

- Frontier Resources: Kodu – Mt Bini

- Frontier Resources: Announcement to the Australian Stock Exchange

- PNG mine not near the Kokoda Trail: Frontier

- Goldmine threat to the Kokoda Trail

- Rudd to fight Kokoda copper mine plan

- Kodu Landowners; Rudd not welcome on the Kokoda Track

- PNG landowners threaten Kokoda blockade

- PNG landowners plan Kokoda track protest

- PM battles to save Kokoda from goldmine

- Aussie Mining Co admits writing Kokoda protest signs

- Kokoda mining worries trekking companies

- Mining company to dig up Kokoda Track

- Kokoda Trail ‘to be re-routed’

- Conservation and Development Options for the Kokoda Track and Surrounding Regions’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. Robert Bino. September 2015

[1] Conservation and Development Optiong for the Kokoda Track and Surrounding Regions’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. Robert Bino. September 2015

[2]State Society and Governance in Melanesia ANU Briefing Note No 4 2008 by Hank Nelson

[3] State Society and Governance in Melanesia ANU Briefing Note No 4 2008 by Hank Nelson

[4] Ibid

[i] Assignment New Guinea. Keith Wiley. Jacaranda Press.1965 P. i