The opening of the Isurava Memorial on the 60th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign was a proud moment for all who fought in the campaign and for those who are determined that their legacy will never be forgotten.

The journey began with the desire of a trekker, Graham Scott, to bring some of the veterans from the 39th Militia and 2/14th AIF Battalions who fought at the battle for Isurava, back to Kokoda for a ‘last parade’.

We were then requested to find an appropriate site for helicopters to land as close to the battlesite as possible and begin the necessary planning to make it happen. As part of our research, we obtained copies of Army Topographical Maps which had been printed from data collected in 1942; some wartime sketch maps from the Australian War Memorial; a portable Global Positioning System (GPS); and as much information as we could glean from the books we had read.

According to the readings we took from our GPS, the battlesite was located approximately one hour’s trekking time south of the where the village of Isurava is located today. We then advised the local clan leader, Mr Ivan Nitua, of our plan to bring the veterans back for a last parade and requested that he organise his people to clear the site and set up some shelters.

Design and Development of the Isurava Memorial by Michael Pender – HPA Projects

Inspector John Rennie an Australian Federal Officer on secondment to PNG, then led a party to explore the battlesite. They did a remarkable job in identifying all the positions occupied by the 39th Militia and 2/14th AIF Battalions during the battle for Isurava. The selection of this ground as the main defensive position to stop the Japanese advance is testimony to the tactical brilliance of the Commanding Officer of the 39th – Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner.

The logistics necessary to support such a group of veterans were beyond their resources. We then enlisted the support of Senator Bill Heffernan who is well known as a bloke who ‘makes things happen’. At Senator Bill’s urging the Australian Government agreed to provide a RAAF Boeing 707 and a medical team to support the veterans. They also provided a RAAF Caribou to fly them from Port Moresby to Kokoda and positioned a Hercules C130 with another medical team at Popondetta in case of emergency. It was a very generous gesture and much appreciated by the veterans and their families.

When the advance party of veterans reached the site they confirmed it was the position they had fought their desperate battle on during 26 – 30 August 1942.

Peter Dorman captured the feeling of these men at ‘The Last Parade’ in his book ‘The Silent Men’:

“It is August 1998, Bomana War Cemetery, Port Moresby. Stan Bisset kneels beneath Butch’s headstone and places a wreath against it. He utters a silent prayer, then stands to attention. With his head still bowed, he clasps his right hand to his breast, then with moistened eyes searching out into space, he offers a last, crisp salute. A few rows away, Bruce Kingsbury’s sister Jean Pope is steadied by her son Dennis, a Vietnam Veteran, as they both bid their silent farewells. Across the beautifully maintained cemetery, veterans, sons, daughters, grandchildren and other kinfolk search for the last resting place of their brothers-in-arms or relative and acknowledge the loss.

“They are here because Stan picked up the baton from idea sparked by Brisbane psychologist Graham Scott, who had walked the trail. Along with two MPs, Charlie Lynn and Kerry Chikarovski, he has arranged and coordinated a final cathartic pilgrimage to Port Moresby and the Kokoda Track. Forty-six veterans, aged between 75 and 88, and 40 kinfolk and supporters, including me, fly into Moresby by ministerial jet, compliments of the Australian Government.

“We are met by police and Defence Force escorts at Jackson airfield, and given a welcoming party by the Australian High Commissioner, David Irvine. The veterans are overwhelmed by the welcome.

“Some apprehension and emotion is experienced as we board the Air Force Caribou and fly over the Owen Stanley’s towards Kokoda. Below, the jungle is compelling, triggering memories and misting eyes as repressed thoughts are confronted, forcing the years to roll back. From Kokoda, we are transported in a thrilling helicopter ride up into the mists of the ranges to land at Isurava. As the clouds part to allow us in, we are met by a colourful sight.

“The emotional ceremony proceeds as anthems, the Last Post and requiems from a lone piper pervade the jungle, However, a highlight for the men is the acknowledgement that the Australian Government is finally recognising the importance of the Isurava Battle. The Minister for Defence and Support, Bronwyn Bishop, who was flown in especially, formally reaffirmed the significance of the four-day battle. There are no dry eyes as the ceremony continues, the veterans trying to relate this peaceful, idyllic scene to the hell-hole of 1942 and its horrendous events.

“After the ceremony, while the veterans search for signs of their old positions, I walk alone into the jungle and look for 9 Platoon’s area. I find an area that fits the description I have been given. The dimness and silence call the ghosts out. I see 9 Platoon lined up: Teddy Bear leading the charge, his Bren gun spurting death. I see Bruce Kingsbury take over as Teddy is wounded, the Bren barking as it continues its killings. On his right, I see Alan Avery grit his teeth and move forward firing his Tommy gun, while Jarmbe follows, firing his .303 with deadly aim. I see the Professor, Hi-Ho Silver and the extending line of men blasting their way into history.

“For myself, ‘The Silent Men’ are silent no more. I understand now the reason for their perceived silence, for their reluctance to talk of the indescribable slaughter they have experienced, and the acts of nihilistic savagery they have witnessed. I understand now their comradeship and strong commitments to each other – an inbuilt support system that renders full credence and authority to the treasured Australian icon of mateship. Through these men, I have also come to know my father. I have come to appreciate the silent burden that war placed on his and their shoulders. In the process, I have also come to know myself more intimately, as I place myself beside him, scrambling and fighting over the stony hills of Lebanon, then stumbling through the mud and jungle of the Owen Stanley’s. I lie beside him in the putrid, stinking trenches and beaches of Gona, warding off disease as much as the enemy. Deep wells of grief and love flood me as I put my arms around him, as I would my children, and attempt to shield him from the surrounding horrors, the assist him to stagger out of the holocaust.

“As the men bid farewell to the brothers and mates who didn’t come home, I feel a stronger bonding with them. After years of pain, examination and conciliation, I pray this Last Parade can release these Silent Men. I will not forget their sacrifice.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Phil Rhoden OBE ED, 2/14th Battalion Commander at the battle of Isurava addressed the veterans:

“We have come here today as pilgrims to be reunited once again in spirit with our fallen comrades of 56 years ago. That is the essential ingredient of a pilgrimage. The journey into a sacred place has an act of spiritual devotion. For the true, the noble and the brave do die in body but their spirit dwells forever more in the habitations and the men they served and loved. Here in this lovely village of Isurava all is now quiet.

But 56 years ago on this day the 26th August 1942, the 2/14th Battalion relieved the gallant 39TH Battalion to take on the Japanese who up until then had unrestrainedly pursued its conquest of South East Asia since that infamous day at Pearl Harbour on 7th December 1941.”The next four days at Isurava are best described by Bill Russell in his history of the 2/14th Battalion. He wrote: “mortar bombs and mountain gun shells burst in the tree tops showering the troops with shrapnel which crashed through to burst on the ground where the noise was de-doubled by the confined space of the jungle. Heavy machine guns cut their own lanes of fire as they chopped through small trees and ricocheted off large trees. Easily concealed snipers fired on our men as they desperately tried to scratch out shallow body holes with tin hats and bayonets.What the Japs had not reckoned with, as they swarmed up between the creek and the track, was the reaction they got.‘In attack after attack they stormed out of the jungle to reel back before steady fire or violent steel. Those who survived the fire of Bren and rifle were met with tommy gun and grenade and those who came through were met with a bayonet”.

“The Australian newspaper in 1994 published a series of anniversary essays edited by Dr David Horner entitled “Battles that shaped Australia”. One of those essays covered the Kokoda Track battle. The essayist, James Morrison wrote: “on the 30th August General Horii, frustrated at the delay to his advance, threw his large reserve into the attack. The Australians began their fiercely fought withdrawal from Isurava to Ioribaiwa. The Australians had held Isurava for four days. They strained General Horii’s supply lines and they held up his advance to Port Moresby. This was the culminating point of the campaign. The advantage passed from the Japanese to the Australians.”

“From 31st August to 15th September the Australians including the 2/16th Battalion and joined by the 2/27th Battalion at Efogi on the 6th September, against vastly superior numbers fought, as Peter Brune describes in the book “Those Ragged Bloody Heroes”, “…a decisive military game of cat and mouse along the track. Company by company, platoon by platoon, section by section they defended until their comrades passed through their lines, broke off contact sometimes only 20 or 30 metres from the enemy and repeated the procedure again and again down the track. To withdraw too early was to allow the enemy too speedy an acquisition of ground. To withdraw too late meant outflanking, encirclement and annihilation”…

‘What enabled the 2/14th and 2/16th Battalions to turn defeat into victory? Outnumbered probably 6 to 1 and certainly out-gunned, the Battalions strained their undoubted professionalism and experienced to the limit. But there was something else, something that was almost intangible.

Firstly, I believe it was the inter-dependence of the unit, one upon the other. Each had a job to do and all depending on the other.

Secondly, it was the ability to hold on after all hope is dead, continuing to fight on until there was scarce breath left in the body.

Lastly, it was the respect that we had for each other. Only a well-trained and happy unit can survive in its hour of need.

Nor should we discount Australia’s hour of peril, the troops did not, they were fully aware of Australia’s dependence upon them.

Complete failure would have meant Japs at Port Moresby and then Australia itself.

“Perhaps paraphrasing the words of Stephen Spencer’s poem are apt: “The 2/14th are men who in their lives fought for life and left the vivid air signed with their honour.

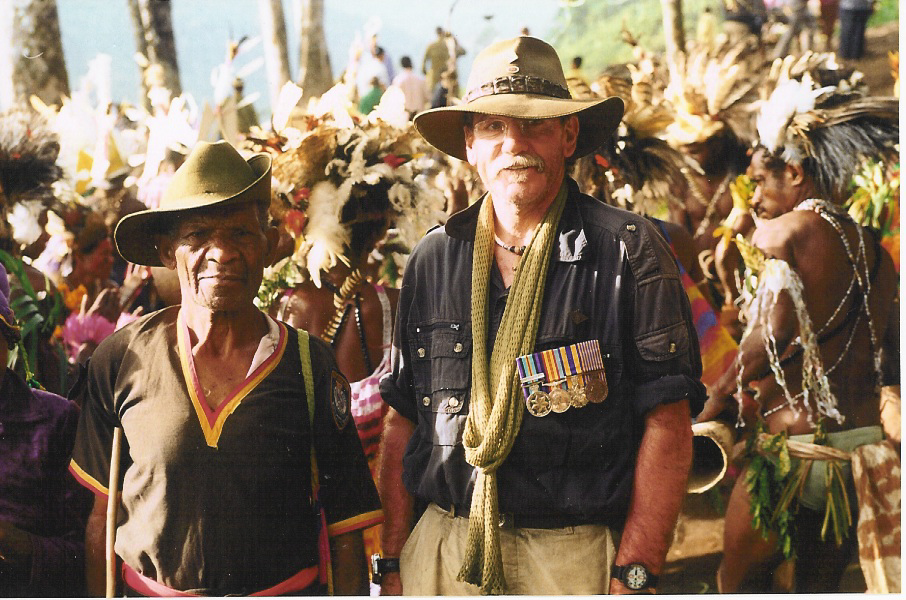

”‘Now is the time for sober thoughts. The time for remembrance with gratitude the fuzzy-wuzzy angels, those sincere, tender and humane people who did so much for our wounded. A time to recall the sacrificial deeds of Kingsbury, Mc Callum and many others, bringing to mind the immortal words of Alan Avery, “I reckon they all should have got a gong” he said.

A time to endorse the thought that the Owen Stanley campaign was a close run thing and that the battle of Isurava was perhaps in the annals of Australian Military History second only to Gallipoli.

‘Those of us now reaching the end of our time should, continue to see that our children and their children embrace the notion that the death of the brave is never in vain and, a good action never lost to the world while there is but one actor or observer left to preserve the record of the event. We, these pilgrims to Isurava, should always remember the future that in the words of Shakespeare in “All’s well that ends well” he wrote, “Such a man might be a copy to these younger times. His good remembrance sirs lies richer in your thoughts than on his tomb.”

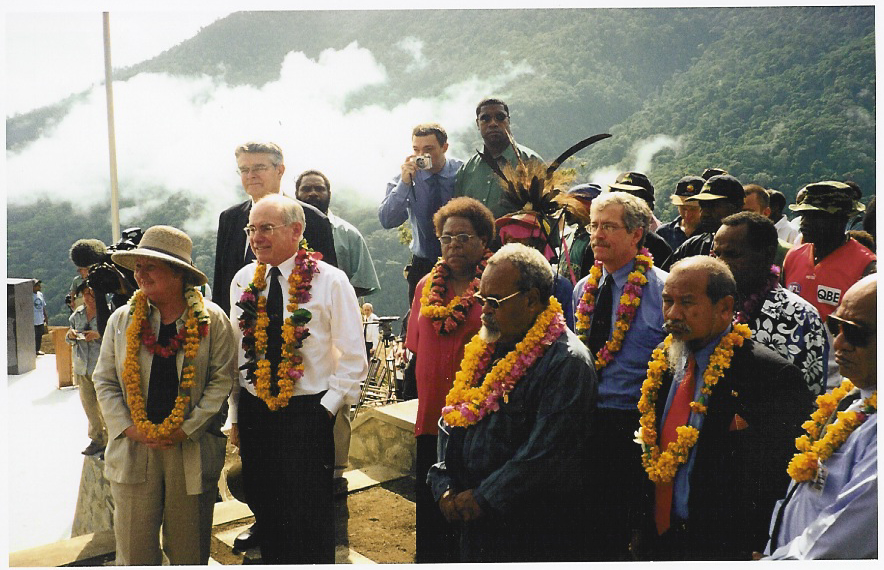

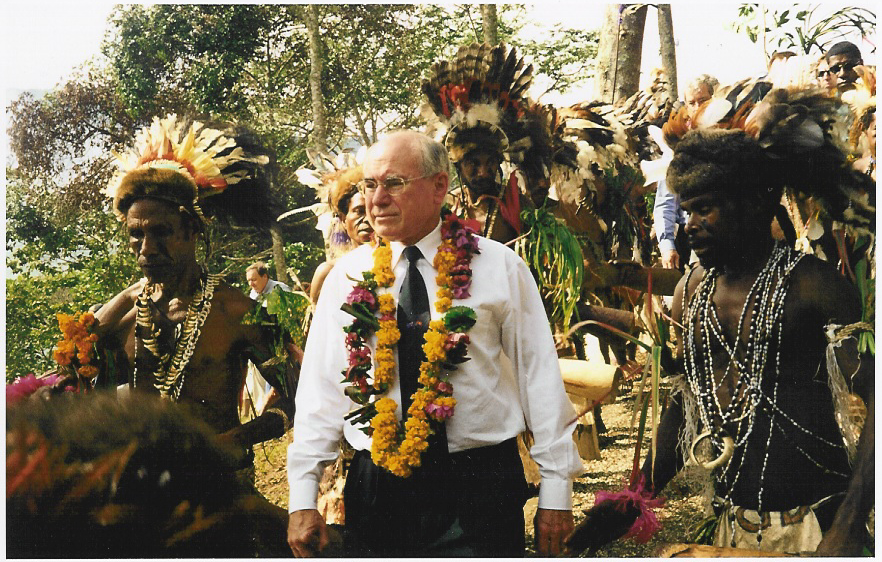

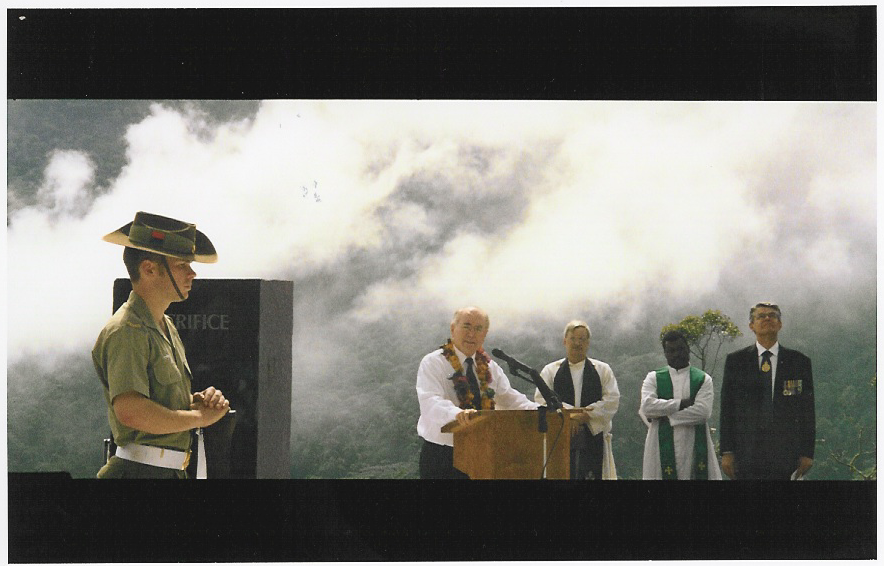

Four years later, on the 60th Anniversary of the battle of Isurava the Prime Minister of Australia, The Hon John Howard, and the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, The Hon Sir Michael Somare, opened a magnificent new memorial on this site. The memorial is a simple structure based on four granite pillars that stand as sentinels overlooking the Yodda valley back towards Kokoda. Each pillar is engraved with a single word: ‘Courage – Mateship – Sacrifice – Endurance’

During the commemoration service at Isurava I was chatting with an old veteran who introduced himself as Albert Moore. He was the legendary Salvation Army officer on the track during the campaign who was captured on film by Damien Parer rendering assistance to our diggers. During the conversation I learned that I had grown up with him – he was the milkman and local Salvation Army officer in my home town of Orbost. We all knew him as a wonderful, kind and compassionate mane – but none of us knew what a hero he was.

The ‘Last Parade’ at Isurava was the first step in the proper recognition of the spirit of Kokoda. My chance encounter with Albert Moore was another reason why their stories should be enshrined in our arts and education systems.

What was “the Professor’s” name?

Am writing an article re Albert moore and the man he lit the cigarette for: Lt Valentine Gardner. would like permission to use part of your article

Dear Mike,

You certainly have my permission and I commend you for your initiative.

Best regards,

Charlie