A 1400% increase in the number of Australians trekking Kokoda after the opening of the Isurava Memorial in 2002 would normally be hailed an outstanding result for PNG tourism, and our shared wartime heritage.

But, for Canberra based envirocrats lurking within the corridors of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA), it had all the hallmarks of an environmental Armageddon!

Their challenge was to neutralise the association of Kokoda with the ‘glorification of war‘, which is anathema to them, and find ways to ‘discourage‘ trekkers from ‘wreaking havoc‘ on an environment few of them had ever seen.

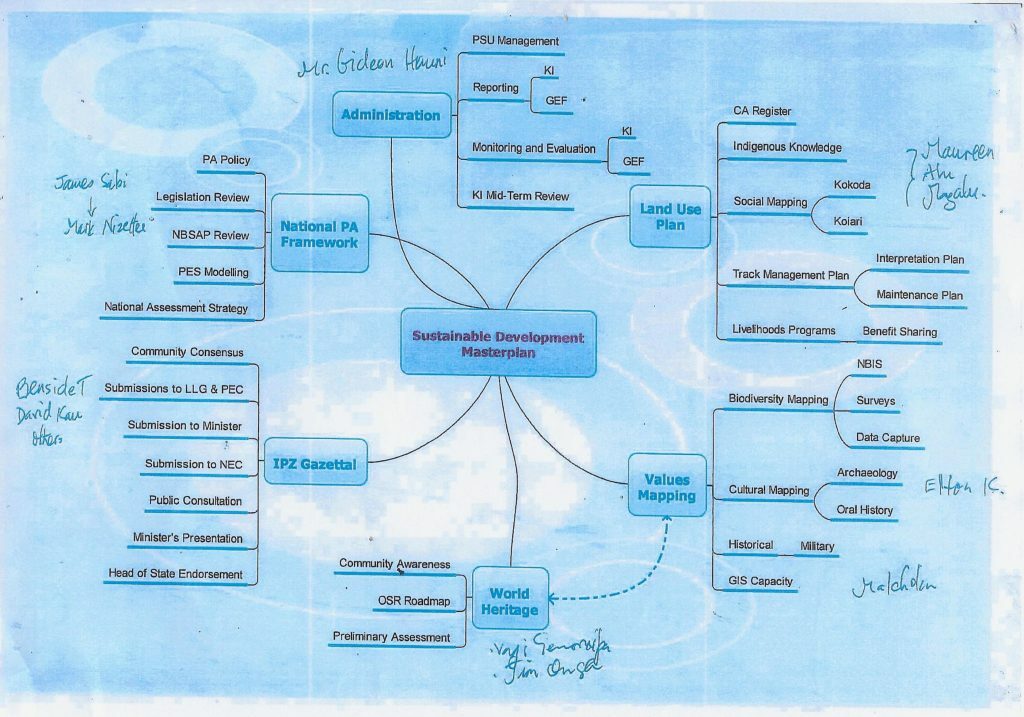

They were also aware of the opportunity it presented for their own ‘army‘ of aid-funded consultancies in the fields of conservation, anthropology, archaeology, social mapping, capacity building, mentoring, gender equity, and a host of other social studies.

The most effective means of neutralising their perceived threat was to seek to offer aid-funded ‘assistance’ to PNG to help them ‘manage‘ the emerging industry which saw trekker numbers increase from 365 in 2002, to 5621 in 2008.

The fact that villagers along the Trail were now receiving sufficient economic and social benefits to break the yoke of subsistence living and aid dependency was not deemed to be as important as the enhancement and future-proofing of their own aid-funded careers.

The discovery of a $3 billion gold and copper deposit on the southern slopes of the Trail provided the ‘emergency’ they needed to derail the mining approval, compensate landowners, and offer to ‘manage‘ the Trail on their behalf.

An aid-funded ‘Joint’ Agreement was duly signed in early 2008 and by the end of the year an environmental management team fresh from Canberra was in place.

By this stage Kokoda had emerged as the new ‘black’ for Australian boomers, their siblings, and those with an interest in our military heritage.

The lure of adventure in the ‘land of the unexpected’ also appealed.

They were soon joined by adventure-seeking bucket-listers and a glut of quasi-adventure companies who arrived to cash in. The influx created chaotic management problems along the Trail as campsites were overcrowded, local guides exploited, and traditional village life disrupted.

There was hope that this would be settled with the arrival of a new, well-resourced management team to coordinate the aspirations of up to 80 trekking companies, and the demands of hundreds of increasingly belligerent landowners.

But in the eyes of the new ideologues from Canberra, trekking companies were deemed to be commercial enterprises capable of exploiting vulnerable ‘natives’ for profit.

The ‘natives’ themselves were also deemed to be ignorant of their own needs due to their perceived lack of education and sophistication. They therefore needed to be made aware that their environment, which they had protected and harvested for thousands of years, had to be protected from any future threats of commercial exploitation.

The engagement of Australian consultants to report on the cultural-environmental diversity of the place was reminiscent of author, Keith Wiley’s pre-independence observation in 1965[i]:

‘In recent years the academics have discovered New Guinea. Grave, plump, portentous, they swarm north in their hundreds each winter where at times they become so numerous that every bush and stone seems to conceal a lurking bureaucrat or anthropologist. After a few weeks or a few months they return home to prepare brisk solutions for all the problems which beset the land. Too often they see New Guinea coldly as an exercise in nation-building to be carried out as quickly as possible, with one eye on the taxpayer at home and the other on some ranting demagogue in the United Nations.

And so, it was with the new regime who self-identified as the ‘Kokoda Initiative’. They soon extended the geographical boundaries of the Kokoda Trail to include Sirinumu Dam on the south coast, a big chunk of the Owen Stanley Ranges, and the wartime beach-head areas on the north coast. This created a smorgasbord of opportunity for consultant environmentalists, anthropologists, archaeologists, social mappers, capacity builders and gender equalisers.

Port Moresby based ‘wan-tok influencers‘ were seduced with offers of aid funded schools and health centres in their villages which enhanced their ‘big-man’ status, and ensured their compliance.

The military heritage of the Trail was downplayed. ‘Mateship’ was formally changed to ‘friendship’ to be more ‘inclusive‘. The Australian War Memorial was bypassed. A compliant American anthropologist was engaged as Australia’s National Military Heritage Advisor in PNG via a recruiting process that could be best described as shonky.

An ‘interpretive design company’ without any military heritage credentials, or previous association with PNG, was engaged ‘for the provision of ‘interpretive services’ to the grandly titled ‘Australian Government Kokoda Initiative Taskforce’.

‘We had to hit the ground running’, the new arrivals panted. ‘Port Moresby is a confronting city and rated as one of the most violent places on the planet. It accosts the senses with its obvious social inequity. When the security agency describes recent events of rape and brutal assaults you cannot help but experience fear.’

Despite the ‘accosting of their senses‘ these fearless young hipsters soldiered on and found that ‘researching and writing for this project was both stimulating and challenging. As there was no clear objective, other than some signage at Owers Corner that would portray the WWII experiences of the people of PNG, we had to start from scratch in workshops and engaging with the local communities.’

Eyebrows were raised over the admission that they had ‘no clear objective’ for the taxpayer funded project, and ‘had to start from scratch’! They were obviously not made aware of the extensive research material available at the Australian War Memorial via awm.gov.au!

In the meantime, the law of the jungle prevailed with trekking becoming more chaotic as the envirocrats now in charge of the Trail failed to introduce any management protocols, and neglected to invest in campsites, toilets, safety, or environmental maintenance. No income earning initiatives were introduced for villagers who were now mere spectators to a passing parade of trekkers. Exploitation of guides, carriers, and campsite owners continued unabated.

Negative reports inevitably led to a steady decline in trekker numbers which have dropped by 46 percent since the environmental cavalry arrived to ‘help’ PNG more than a decade ago.

The first hint of their strategy soon after they arrived was an innocuous post in their first Kokoda Track Newsletter on 1 May 2009. It advised that:

‘A Track Analysis will be undertaken shortly to determine the works program required to repair the Track (sic) to Australian Standards for class 4 walking Trails. This is a minimum standard and seeks to provide sustainable use for the Track (sic). Once this report is complete it will be circulated.’

A perusal of the ‘Australian Standards for class 4 walking trails’ revealed these gems tucked away in the document:

‘Opportunity for visitors with advanced outdoor knowledge to find their own way along often indistinct tracks in remote areas. Users can expect frequent opportunities for solitude with few encounters with others.

‘Toilets of minimal design to be provided only where necessary for environmental purposes.

‘Recommended max party size 6.

‘All publicity to be discouraged. Not to be included on maps except for internal management purposes. Authors will be encouraged to keep route descriptions vague (eg in accounts of past expeditions). Photographers and publishers will be encouraged not to identify the precise location of photographs taken in areas accessible only by T4 tracks.

‘Licences may be issued on condition that guided parties conform to the recommended party-size limit and to the guidelines relating to the publicity of tracks and destinations.’

This is obviously why there is not a single toilet that meets the most basic of hygiene standards for trekkers today. A maximum party size of 6 would make it economically unviable for trek operators. This would lead to the loss of any chance of a sustainable income for local villagers and consign them to a life of aid-dependent subsistence living. The lack of publicity would effectively sabotage PNGs most popular tourism destination i.e. The Kokoda Trail.

Under their ‘class 4 walking trails’ standards trekking would be limited to a few mung-bean munching freeloaders and unwashed tree-huggers from the extreme environmental movement!

It took Covid to expose the duplicity of their multi-million-dollar aid-funded agenda over the past decade. There is nothing left in the bank; villagers have had to revert to subsistence living; no initiatives have been introduced to commemorate our shared wartime heritage; trekkers will no longer be disturbing the sensitive environmental solitude of the place; and, more importantly, their bloated six-figure, tax-free salaries have not been affected.

Mission accomplished!

Footnote:

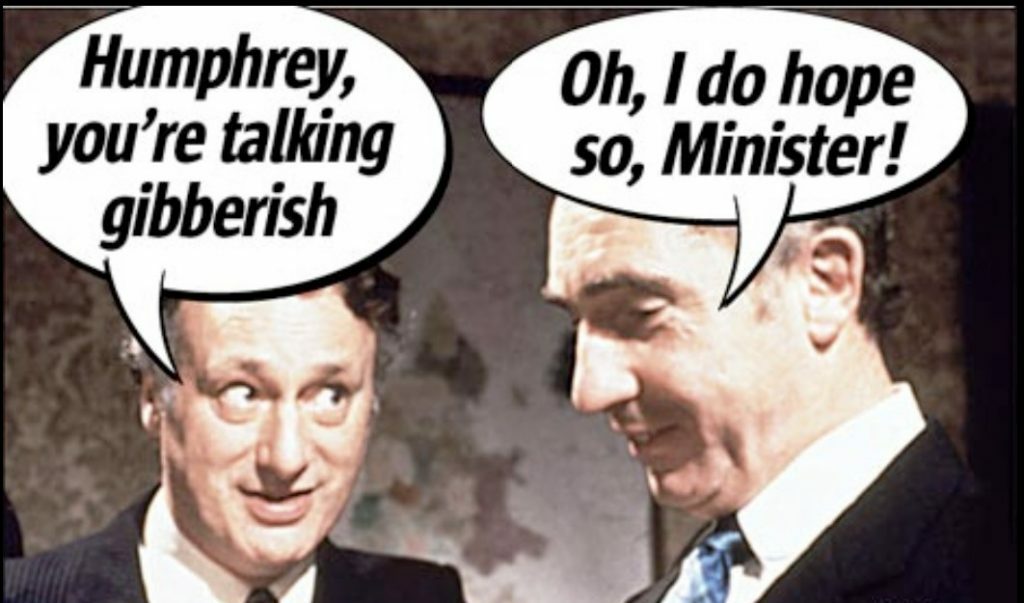

‘Yes Minister‘ is easily acted out by Australian officials in the PNG ‘Kokoda Initiative’.

Ministers for ‘International Development and the Pacific’ do not stay long in their portfolio. There have been five over the past six years – one served for less than six months, and the longest stayed for a little over two years. They are therefore hostage to their bureaucratic ‘advisors‘ as they seek to come to grips with the cultural complexities of the ‘land of the unexpected‘ within a ‘Parliament of a thousand tribes‘ near the top of the international ladder for institutionalised corruption, and the bottom of the ladder in regard to human development indices.

Expatriate Australians who have lived and worked in PNG and the Pacific will attest to the fact that it takes many, many, years to understand and empathise with the ‘Melanesian Way‘.

PNG Government officials are therefore fair game for Australian bureaucrats who have little Ministerial oversight; a hidden ideological agenda; a large aid budget; and the knowledge that PNG officials and ‘influencers’ will support any initiative that has an aid dollar attached to it.

They can therefore proclaim: ‘I understand your concerns Minister, but as you can see, this is what PNG wants!’

Sir Humphrey would be very proud.

[i] Assignment New Guinea. Keith Wiley. 1965