‘I have taken the liberty of copying the full text of two of Masuko’s letters because I believe that in them lie the very heart and soul of this story. I want others to have the opportunity to share with me the beauty of thought contained in her letters, and, more particularly, of her humble and sincere cry from the heart for peace.‘

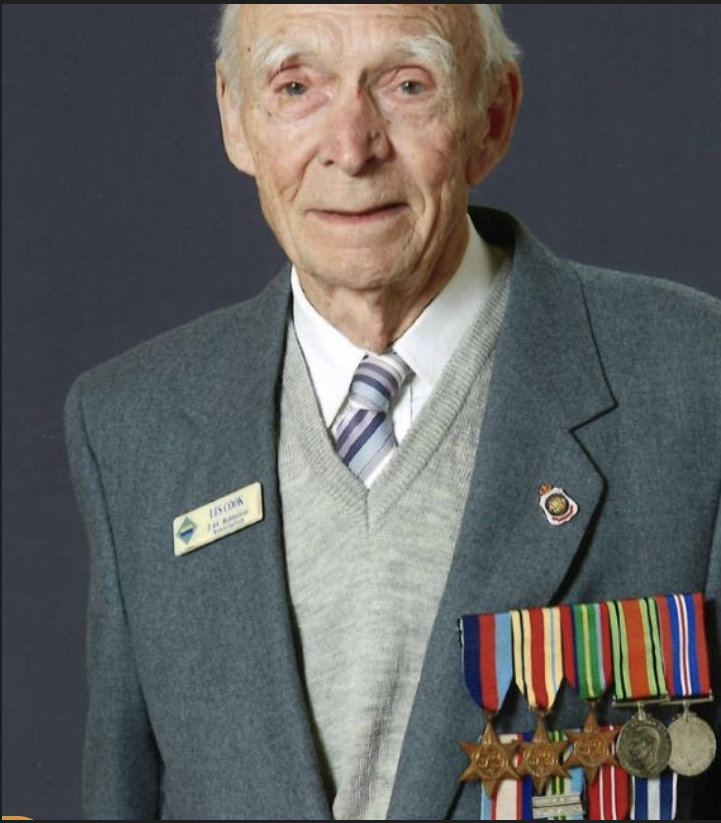

Today we salute and celebrate the 100th birthday of a remarkable, unsung Australian hero – WW11 veteran, Corporal Les Cook.

Les joined the 2/14th AIF Battalion, the most decorated army unit in World War 11, and served in the Western Desert, Greece, Crete, Syria, across the Kokoda Trail, at Gona and Sanananda, Lae, Shaggy Ridge in the Markham Valley, Balikpapan in Borneo, and with the Occupation Forces in Japan from 1940-1947.

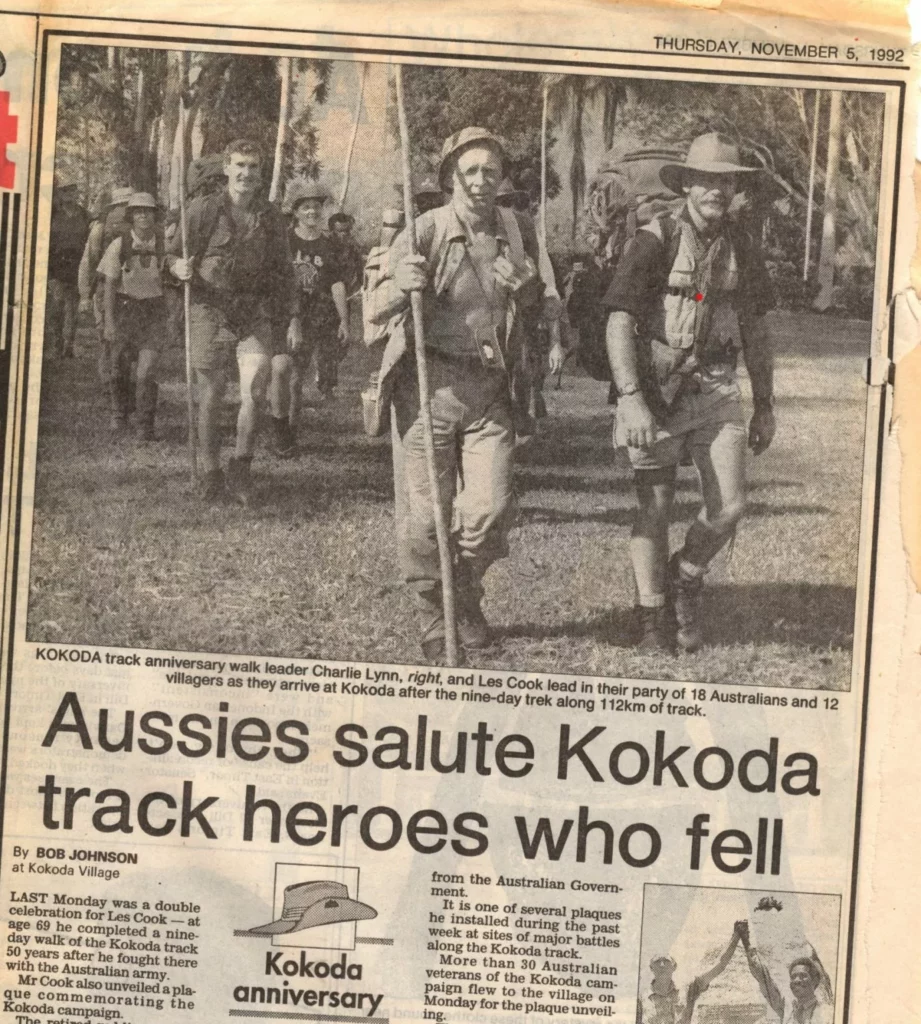

I first met Les when he applied to join a trek we had planned to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the raising of the Australian flag at Kokoda on 3 November 1942.

When I asked him why he wanted to join the trek he replied, ‘I fought across it in 1942.’

I worked out that he would therefore be around 70. He assured me that he kept himself ‘pretty fit’ so I suggested we could organise a porter for him. He shot back ‘I’m only 70 mate, not bloody 90!’.

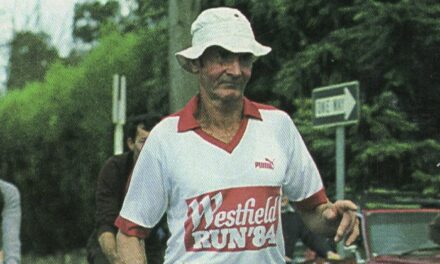

He joined us in Port Moresby with an original canvas and leather ‘Paddy Pallin’ backpack and carried his gear all the way across the Trail – just has he did 50 years earlier. Marian Frith, a journalist from the Canberra Times, captured the trek in a feature article – A Hard Slog to Kokoda.

Les was an unassuming hero. He was offered promotion many times but chose to remain as a corporal because he wanted to stay in the field with his mates.

Whilst he saw it as his duty to fight for the country and the people he loved so much as a young bloke he also understood the futility of war when he was required to bury Japanese soldiers killed at the battle of the beach-heads at Buna and Gona in 1943.

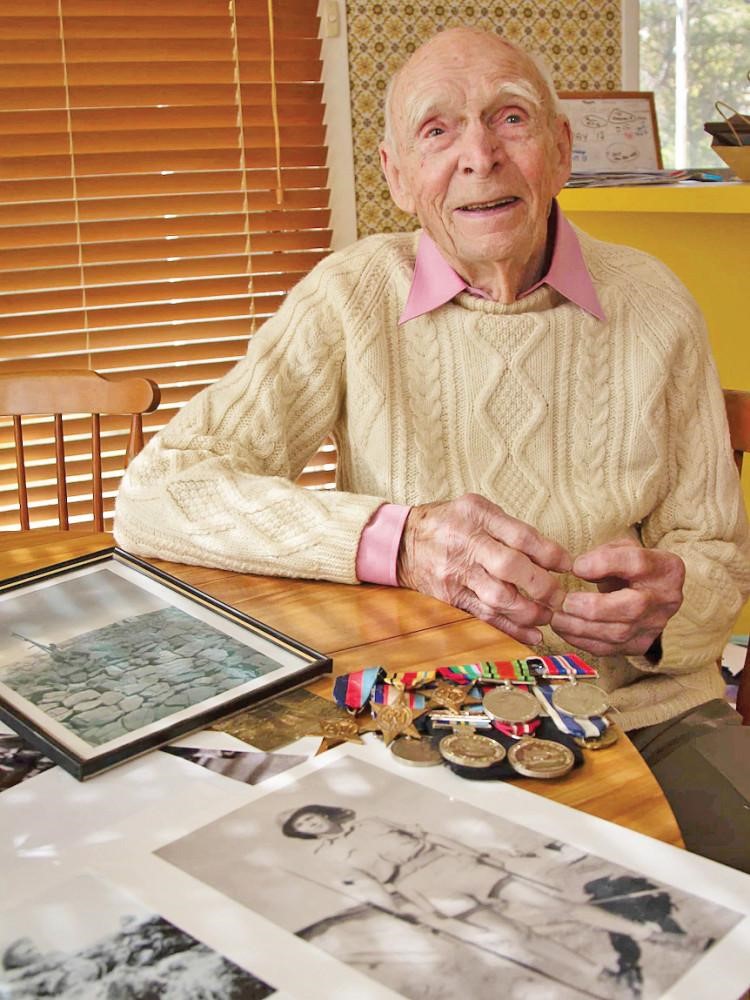

He later wrote of his attempt to return the belongings of one of the dead soldiers to his family in Japan after the war in an article he titled ‘The Spirit of the Yasukuni Shrine’:

‘A doll in a glass case stands in a prominent place in our home in Canberra. About 40 cm tall, the figure is of a girl in traditional Japanese

costume. Its striking beauty has always attracted the attention of visitors, and I have been asked about its origin.

‘The doll was given to us by the Kondo family of Japan in thanks for returning to them personal effects of a member of their family, a Japanese soldier who was killed in New Guinea during the war. In addition to its sentimental value as a token of gratitude, the doll is a constant reminder to me of the tragedy of war.

‘As I gaze at it today my thoughts take me back almost sixty years to the fever-ridden coastal swamps of New Guinea where this story began. In my mind’s eye I see the desolate scene again so vividly and in such detail that, for a moment, I feel as though I am actually there. I hear the incessant rattle of rifle and machine-gun fire, sense the oppressive heat and humidity and the cloying stench, and feel the numbing tiredness that dulls all sensation, even fear. I see the gaunt, exhausted faces of my mates, and I remember those who are gone. With the sentimentality that comes when we grow old to those who have lived thought desperate battles, I am saddened by the awful human cost of war.

‘But then I think of the pleasure I felt at being able to return the articles to the soldier’s family, and, more especially, I recall my emotions when first I read the letters of thanks I received from Masuko Kondo, the daughter-in-law of the soldier’s sister. Looking through those letters again now, I am moved by her sincerity and compassion to tell this story of war and peace, and hope for the future. Masuko’s letters are an integral part of my story – indeed, it is woven around them.

‘Toward the end of 1942 the battle around the small village of Gona on the north coast of Papua New Guinea had raged incessantly for three weeks. Such had been the intensity of the close-quarter fighting that neither side had been able to bury their dead. When finally we broke through to the beach we were confronted by a scene that almost defies description. Gona was a shambles! Upwards of one thousand bodies from both sides in various stages of decomposition lay scattered or in heaps in this very small area. While some of our troops moved on to contain the Japanese forces to the west of Gona, the rest of us were employed for the next three days on the gruesome task of burying the dead. It was an experience none of us can ever forget.

‘It is customary for burial parties to collect any official enemy documents or private papers for intelligence purposes. Among the articles I had collected was a flag and a diary taken from one of the dead Japanese soldiers. The flag was made of white silk, about 60 cm square with the red circle of the Japanese emblem in the centre, and what we understood to be good luck wishes from family and friends written on the white background. The diary was a small leather-bound book. I was allowed to keep these articles and took them home with me as souvenirs at the end of January 1943.

‘I was in Balikpapan in Borneo when the war ended and went to Japan with the Australian contingent of the occupation forces. While in Japan we took our turn with other British Commonwealth countries and the Americans on guard duties in Tokyo. One of the places we guarded was the Yasukuni Shrine – a Shinto shrine dedicated to the spirits of those Japanese who have died in battle. The attendants at the shrine were all old soldiers, one of whom could speak English. While discussing the differing aspects of the Shinto and Christian religions with him I told him of the flag and diary. He explained that, in Japanese family remembrance ceremonies, there is deep spiritual significance in having something that was with the deceased relative at the time of death. Becoming aware that the articles I had taken home as souvenirs would be of such great comfort to the soldier’s family, I realised that it would be morally wrong for me to keep them. I resolved then that I would return them to his family if possible.

‘Following my return to civil life in 1947 I made several attempts over the succeeding years to see if I could locate the family, but without success. Indeed it appeared to be an almost impossible thing to achieve from Australia at the time. Even the staff at the Japanese Embassy in Canberra seemed unwilling to help.

‘In the early 1970s I gave most of my wartime memorabilia to the Australian War Memorial, but for some inexplicable reason I kept the flag and diary. Perhaps, subconsciously, I was still hopeful that I would be able somehow to return them to the soldier’s family. I can’t remember. Whatever the reason, it was probably the most crucial of the several otherwise unrelated events that eventually made their return possible, which leaves me wondering sometimes if there is an unseen hand governing such things, or if it is all really just a matter of chance.

‘Some years later a student from Thailand was living with us and attending the Australian National University in Canberra, where one of her subjects was Japanese. Her tutor, Mr Kaneko, was a Japanese citizen. Mr Kaneko was able to ascertain from the diary the soldier’s name and home address at the time of his enlistment. Our Prime Minister, Mr Fraser, was planning to visit Japan in 1976 and several Japanese journalists had come to Australia in connection with the visit. Mr Kaneko brought these journalists to our home where I gave them all the information I could, and they took the flag and diary back to Japan with them undertaking to try to locate the soldier’s family.

‘The journalists were not hopeful of success, and it seemed to me unlikely that I would ever hear from them or see the articles again. It came as a very pleasant surprise when a few weeks later I received the following letter from Mr Masuko:

‘Dear Mr Cook,

We have not met before, but I am writing you this letter of thanks to express my gratitude to you from the bottom of my heart.

Today we suddenly received from a Mr Kaneko living in your country some glad news that we never expected. That is that you have been taking care of some things left behind by my aged mother’s brother who died in the hateful Pacific war, and by your kindness we shall be able to have them returned to us.

When we saw the airmail letter in our mailbox, that in itself was unbelievable for people like us who live far out in the countryside. We read the address over and over to be sure it was for us before we dared open it. As we read it, we found ourselves facing something we had not dreamed of, something dear to us and very joyous, and we wept tears mixed with emotion, fond memories, and joy.

Mr. Cook, thank you very much, with all our heats we thank you deeply. Though over thirty years have elapsed since the war ended you have been good enough to take care of these things for so many years, and besides you have asked so many people and have gone to so much trouble in order to return them to us. It is more than we could ever have imagined.

How thankful it is for someone whom we do not know, and have never heard of, from a distant country to go to so much trouble and concern for us.

I shall promptly inform the office of Japan’s Welfare Ministry (the government department responsible for finding the family) and Mr Ozawa of the Mainishi Newspaper. (Mr Ozawa was one of the journalists who came to our home with Mr Kaneko).

This year’s O-bon festival will soon be held in August. In Japan, at the time of O-bon we greet into our homes the spirits of our deceased ancestors; it is the custom for all in the family, even those who have left to work in the cities, to return for this ceremony and join in consoling the dead. With this once-in-a-year important O-bon soon to begin, receiving the belongings of the deceased uncle through you kind sympathies is, as far as we are concerned, the best way of giving my uncle consolation.

When my aged mother and her brother were still small they lost their parents and faced many hardships in life but held on despite it all. Then my mother was robbed of her brother by that war. In the sorrowful days that followed the only article by which she could still feel the presence of her brother was a faded photograph. But when she learnt that she would be able to touch belongings that were on his person at the time of his death, she could not keep back the tears of gratitude for all you have done.

Our deepest regret is that we cannot tell you our thanks directly face to face.

Praying here in distant Japan that you shall always and always be healthy and blessed with happiness, I lay my pen down.

From my aged mother and from all in the family, heart-born regards.

Masuko Kondo’

I replied immediately with details of her uncle’s death at Gona: how I had come by the flag and diary, and the circumstances of their return. I told her that in the final phase of the battle the Japanese soldiers had been invited to surrender, but had chosen to die fighting. We had buried her uncle and his comrades in soldier’s graves where they fell. I consoled her with the knowledge that her uncle had given his life serving his Emperor and his country, and that the family should remember him with pride. I ended my letter with what I thought was an appropriate quotation from Macaulay’s famous poem “How Horatius Kept the Bridge” as an epitaph:

“Then out spake brave Horatius, the captain of the gate

To every man upon this earth, death cometh soon or late

And how can man die better, than facing fearful odds

For the ashes of his fathers, and the temple of his gods.”

Masuko’s reply to my letter follows:

‘Dear Mr Cook,

Thank you very much for your kind letter received the other day. I should have written you a reply at once; I apologise profoundly for having put off the reply this long.

The items that you cared for for so many long years arrived at our home a few days ago. Thank you, warmly and from our hearts. My whole family, beginning with the aged mother, were deeply choked with emotion when we held in our hands the items left behind by the deceased. The way in which you carefully preserved these items for thirty three years reveals to us you kind nature.

In the earlier letter I wrote about the O’bon ceremonies. The items did not arrive in time for the O-bon, but even so at this year’s O-bon we were able to propitiate the spirits of the dead members of the family more specially with deeper emotions.

According to your letter, you say that you buried a large number of corpses of Japanese soldiers, and we really are thankful to you for doing this. It seems a shame that we are the only ones who know about this fact. Here at our place we have been discussing whether or not it wouldn’t be fitting repayment to kindness of yourself and others like you, if we would let other families who have lost someone in the war know about what you have done.

When our local newspaper made a big story of how you sent us these items of the deceased family member there was a big reaction to the story. Just the other day there was a letter to the editor of the paper from a reader who said that he cannot get rid of the thought that the bones of many of his soldier friends are lying in New Guinea exposed to the elements, and he wishes his country would do something about it and help collect those bones. As soon as we read this we telephoned the writer and told him everything you said in your letter. When he heard how someone from another country had kindly buried our soldiers he also was very moved. Even now those people who managed to live and to return to our country alive still have scars from the war deeper than we can imagine.

I, myself, lost a brother in the war. After his graduation from the old army officers’ school he went to Burma where he died at 24, a colonel. Probably he felt a great pride in being able to die for the country and for the Emperor, but that is how the Japanese were educated to think at that time. No matter for what reasons, there isn’t anything as awful as war, with so many people’s lives being taken from them. It seems there can be absolutely no excuse for this from a standpoint of humanity. And yet, wars follow upon wars on the globe and many lives are lost. This is very sad. With our small weak power we just hope for the building of a peaceful world, and do our best every day for this end.

With prayers from the heart that days of peace and happiness will always continue to shine on you, Mr Cook, I offer you this letter of thanks.

Respectfully,

Masuko Kondo

My wife, Betty, and I were planning to visit the U.K. in 1977 and were considering going via Japan to meet the Kondo family. I must say that I had some reservations about this as I wondered how my own sister would have felt if the situation was reversed, but the suggestion was welcomed warmly by Masuko and we made arrangements to meet at Hiroshima. A transport strike in Japan while we were there made this impossible, but Masuko and her husband were able to come to Kyoto to meet us. Betty had crocheted a large woollen shawl as a present for the soldier’s sister, but to her great disappointment, was unable to give it to her in person because she had not been well enough to accompany them. Masuko took the shawl back to her mother-in-law.

We didn’t know that they had sent us the doll as a thank you gift until we returned to Australia almost three months later.

Masuko was the mother of two young adult sons when we met at Kyoto in 1977. As a grandfather I have had the experience of watching the relationship between our own daughters and their children as they grow to adulthood. It is with the sensitivity and wisdom that apparently comes to most men only with age and family responsibility, that I can now fully appreciate the anti-war sentiments expressed in Masuko’s letters. I am sure that she echoes the silent prayer that has arisen in times of conflict from every mother of the world since time began. I remember now with shame that I have no thought to the anguish my mother must have suffered when soon after my seventeenth birthday I enlisted in the A.I.F., and was away for almost seven years – most of the time overseas.

I have taken the liberty of copying the full text of two of Masuko’s letters because I believe that in them lie the very heart and soul of this story. I want others to have the opportunity to share with me the beauty of thought contained in her letters, and, more particularly, of her humble and sincere cry from the heart for peace.

Masuko’s last letter to me ended with the words “I hope that friendship between our two countries and our two families last forever.” I share this hope.

Snapshot of a remarkable life

Raised in rural Victoria before heading off to war, LES COOK hasn’t even visited Cape York, let alone lived here. So why is his story relevant to readers? The truth is that his story is relevant to every Australian. The 99-year-old sat down with Cape York Weekly editor MATT NICHOLLS in February to share his story …

WE could all learn a thing or two from humble war hero Les Cook.

The top-shelf gardener, proud dad and gym regular is still living his best life in a quiet suburb near the Canberra Hospital.

Earlier this year I found myself in the nation’s capital at the historic Australian War Memorial and had a lightbulb moment – for Anzac Day this year I should write a piece on a World War II veteran.

So I did some research, made a few calls and emails and stumbled upon Les.

The interview was set up by his wonderful daughter Debbie and my partner Emily and I lobbed up to his house on a sunny morning in early February.

I remember thinking as I drove to his house how hard it would be to interview a man who had lived such a long and meaningful life.

For a 99-year-old, Les was full of beans and we sat in his backyard drinking coffee, chewing the fat and discussing some of his vivid memories from wartime.

The only instruction I was given by Debbie was not to try and upset him – a TV crew had interviewed Les a few years earlier and pushed him to exhaustion trying to get him to be emotional on camera.

For me, that was an easy request as I didn’t want to talk to him about the worst of the war.

I was eager to learn about how life had changed for Les and his mates when he came home and what Australia was like in the post-war era.

We got sidetracked a few times but I walked away in awe.

FAMILY DUTY

THE first thing you need to know about Les Cook’s war experience is that he didn’t have to serve.

He was 17 when he enlisted in May 1940 and you had to be at least 20 or 21 at the time.

His father Ernest, who served in the First World War, also lied about his age, telling recruiters he was several years younger so he could enlist again.

“You could have said your name was Ned Kelly,” said Les.

“You didn’t need any evidence. We both enlisted under our own names and I’ve always thought that mum could’ve rung up and had us kicked out, but she knew we would’ve just gone and enlisted under a different name.

“We felt that we had a responsibility to support the stand.”

Les Cook hopes to get a letter from Queen Elizabeth II, not Prince Charles. Picture courtesy ABC Canberra.

Les’ father actually served for two armies. He was first in the British Expeditionary Force and joined the Australian Imperial Force for World War II.

“I was born in England and my second birthday was on the boat (to Australia),” Les said.

He was 16 years old when he first tried to enlist after the war broke out in 1939.

“I think they said ‘go and try the boy scouts’,” Les recalled.

It wasn’t until after the battle of Dunkirk in that he was finally successful in joining the army.

“It was the thing to do in our generation,” he said.

“I remember when I left work, the head of the organisation talked of courage, and I remember saying at the time, it would have taken more courage for me not to have enlisted.”

DEPLOYMENT

IF circumstances were different, Les would have a passport to be envious of.

He shipped off to North Africa and did stints in Greece, Crete and Syria. He came back to Australia for six months before his unit was sent to New Guinea to try and stop the Japanese advance on Port Moresby.

Having survived that and a trip to Borneo – as well as a second bout of malaria – Les didn’t stop serving when the war was declared over in 1945.

He volunteered to go to Japan in a peacekeeping-type role and was discharged from the army in 1947.

Ask those who know him and Les was a fine soldier who served his country with pride and honour.

But ask Les and he’ll play down his role, shouldering arms to any questions that paint him as a hero.

“It’s embarrassing to be held up as something that you’re not,” he said.

“As one man said, we weren’t soldiers, we were heavily-armed civilians – and I liked that definition – because that’s what we were.

“We were just ordinary people. Yes, there were some who were heroic and some who were extraordinary, but for the most part, we were just ordinary people, and, just like in life today, some of us were just making up the numbers.”

Max Caldwell and Les Cook at a gathering of the 2/14th Battalion 2nd AIF.

While Les believes Anzac Day is an important day and attends services with pride, he doesn’t believe he deserves special praise.

“When I go to these services, I think, ‘They’re talking about you’,” he said.

“We were just the generation that happened to be alive at the time. People ask me, ‘What did you do in the war?’ and I tell them, ‘I walked among kings’.”

As we sat in the sun on a mild Canberra morning, I told Les the story of my grandfather’s uncle, the late Corporal Tom Fletcher who signed up to be a medic in the same war because he wanted to serve but didn’t want to kill.

Tom served alongside the inspirational Corporal John Metson, who crawled in agony down the Kokoda Track for three weeks after he was shot in the ankle.

Metson refused to be stretchered because he didn’t want his mates to carry him, so bandaged up his hands and knees and crawled through the jungle.

My grandfather’s uncle was left in a New Guinea village to look after the wounded men while those who were fit enough pushed on for reinforcements.

Before help arrived they were discovered by the Japanese forces.

Unarmed, they were brutally killed then and there.

“That story will tell you more about the war than I ever could,” said Les, who has written about Metson and his crew and speaks highly of their bravery. Still, he prefers to remember the fonder and funnier times at war.

“In Borneo, we were cut off for three days and two nights and we didn’t get much sleep,” he said.

“There were two blokes in a shell hole that was half full of water. One of the blokes went to sleep and his steel helmet pushed his head under the water.

“The other bloke heard him breathing bubbles under the water and pulled his head up.

“Another time a bullet came past an officer’s head.

“The officer turned around and yelled out: ‘Look out where you’re firing, you nearly hit me.’

“And the bloke said to him: ‘There were two Japs the other side of the tree you were behind, and I’ve just shot one of them.’”

BEFORE AND AFTER

LIFE was certainly no picnic for a young Les Cook.

He grew up on a dairy farm in the Gippsland region in south-east Victoria and had a rifle in his hands when he was seven.

Two years of secondary school was all that was required before he landed a job with the railways.

“You got an extra sixpence a day if you learnt Morse code so I did,” he said as he talked about how he started as a signaller for the army when he first enlisted.

“That wasn’t what I signed up for and later I was carrying an anti-tank rifle and in Syria, I carried the Bren gun, the anti-aircraft machine gun.”

When he returned from Japan in 1947, he caught the train from Sydney to Melbourne to make a new home for himself after seven years of service.

He signed up single but had an inkling he had someone special waiting for him in Melbourne.

Les first saw Betty on the train in a rare stint back in Australia between his Middle East tour and his pending New Guinea mission.

He had been in hospital and was preparing to be permanently discharged when he spotted Betty on the Hampton line.

“He didn’t have the courage to talk to her on the first day but thought if he was on the same train the following day he might have a chance to see her,” said daughter Deb, who made sure her father didn’t leave out any good bits.

As Les recalled: “She lived in the same suburb (Hampton) and I walked her home.

“We talked for about an hour and exchanged details.

“When I went (to New Guinea) we hadn’t even held hands. But she’d write to me and we wrote for about three years.”

He recalls telephoning Betty when arriving in Melbourne.

“I would have still been in my uniform because I didn’t have any other clothes,” he said.

Reunited in person, they married the following year and had their honeymoon in Cairns.

They went on to raise three daughters – Annette, Judy and Debbie and spent most of their life in Canberra.

“I was offered my old job back at the railway but I wanted a job that kept me outdoors,” Les said.

He took up carpentry but as the nation struggled in the post-war era, he decided that a government job would be best for raising a family.

He accepted a position with the Commonwealth in Melbourne and later transferred to Canberra, working in geoscience.

Every day he would return home for lunch to be with Betty, who was a homemaker without a network in the capital.

“We had a happy marriage. We were friends as well as lovers,” he said with a tremble in his voice.

He looked after his wife until the end.

EYEING A CENTURY

YOU can’t help but admire Les’ attitude towards life.

His house is tidy, his garden full of fruit and vegetables and his zest for living is steadfast.

“I still go to the gym, you know,” he beamed at me, probably hinting that I should be taking a leaf out of his book (he’s right).

“For my 99th birthday the gym gave me a life membership!

“I’m hoping I can get a bit out of them.”

Les will turn 100 on January 10 next year, although his service record says he has already hit the milestone.

He hopes Queen Elizabeth II will still be alive to write him a letter for his birthday.

“For the 75th anniversary there were eight of us sent up to New Guinea and Prince Charles and Camilla were staying in the same hotel,” Les said.

“Camilla came and talked to us for about an hour, but Charles is … different.

“If I make it to 100 I hope the Queen is still there.”

ANZAC DAY

WHILE Les believes the days of him and his World War II mates are numbered at Anzac Day ceremonies, he isn’t worried that the commemorations will drop off in the future.

“The young people are showing so much interest in it. They don’t need any push to do so,” he said.

“It’s a very significant day. There’s no doubt about that.”

In a piece he wrote not too long ago, Les penned: “When you stand in silent remembrance on Anzac Day, or when you stand before a cenotaph or at the gates of a war cemetery and read the words, ‘Their name liveth for evermore’, think of John Metson; of his fortitude, his determination not to be a burden to others, and his cheerful acceptance of the awful situation into which he had been thrust.”

Mr Les Cook,

Thank you for your service. You have my utmost admiration for everything you have done to repatriate items of a deceased soldier to his family.

May I wish you the happiest of birthdays and agai, thank you, you make me proud to be Australian.

My sincere best wishes,

Mark Dando

A Truly remarkable Man. Thank You for Your Service. Happy Birthday!

Happy 100th birthday Les, from the son of a veteran who served in New Guinea. Congratulations on your milestone,👏👏👏👏

A very happy birthday to an incredible man. God Bless. Xx