Sydney Morning Herald, November 25, 1995

Charlie Lynn’s holiday package includes a good measure of fear, exhaustion, injury and shock, which may be why Australia’s largest companies think he’s great. Marc Llewellyn reports:

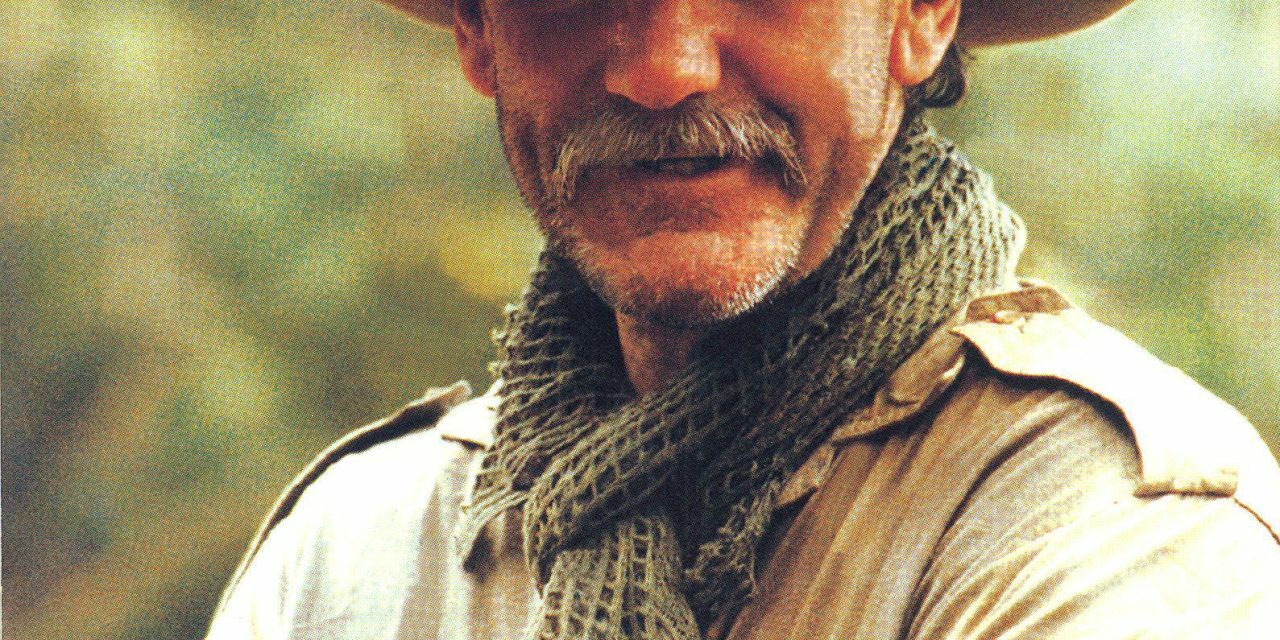

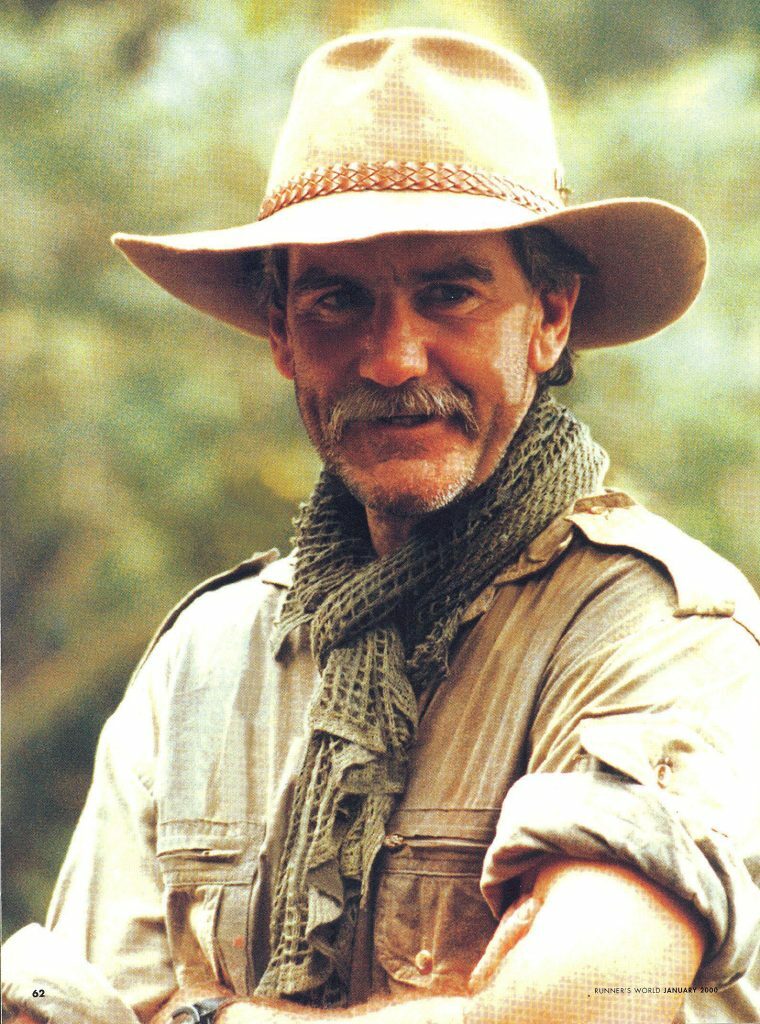

THIRTEEN hours up a mountain and Xiaoling Liu is crawling on her hands and knees through the mud with a heavy rucksack on her back. The 42-year-old senior research scientist is almost blind from an insect bite which has left her face and body badly swollen. Both her ankles are twisted and she is close to giving up. Bending over her is Vietnam veteran and professional motivator, Charlie Lynn. He whispers in her ear the only words that will keep her moving: “Attack! Attack! Attack!”

Ahead, hollow-faced with exhaustion, 28-year-old Karen Dunshea, a human resources consultant, stumbles through the dark. Her miner’s lamp, strapped to her pounding head, picks out a few metres of almost vertical track through the rain. She kicks her foot into the mountain, jabs in her bamboo walking stick and wrenches herself a step further upwards. Another kick and – thud. The Kokoda Track thumps her in the face and she slips, flailing into Lynn’s legs. If a doctor were here, Dunshea would be admitted to hospital – but all she has is Charlie.

“Come on, you’re a psychologist,” he soothes, referring to her university degree. “You above all know it’s mind over matter.” “You bastard,” she mutters. The five other members of the corporate CRA team see her fall as a chance to grab a few seconds’ rest. But then it is up, and up again, to the top of the jungle ridge.

Today is the hardest day of their lives so far, more difficult even than yesterday’s gruelling 14-hour slog. Tomorrow, however, will be even harder.

CHARLIE Lynn, who recently took Ted Pickering’s seat in the NSW Upper House, was also once the NSW 24-hour ultra-marathon record holder and director of the Westfield Run. He is convinced the nine-day trek across Papua New Guinea’s Owen Stanley Range is the most difficult thing he has ever done.

When he throws in a few “tasks”, such as carrying a volunteer on a jungle-made stretcher across dangerous rapids and up a treacherously wet mountain slope, the “toughest trek in the world” mutates into possibly the world’s most difficult leadership and team-training scheme.

But it is not the only one. There is a worldwide boom in tough corporate training regimes and Australia is not dragging its heels. Companies such as Outward Bound, Outland Expeditions, Adventure West and the Australian School of Mountaineering are all attempting to put some mettle into corporate types by putting them through extreme situations. The tougher the situations, the more likely that their companies will benefit from these battle-hardened staff.

The CRA team members, who had never met each other before, were experiencing Lynn’s inaugural Air Niugini/Adventure Kokoda Leadership Program. Lynn, however, has already completed nine “reconnaissance” trips along the track, during which a few of his companions wished they had stayed at home.

Lynn cheerfully recounts the story of a trekker who went insane before collapsing into unconsciousness. His fellow adventurers, noticing his skin was cold and clammy, desperately raced to cover him in sleeping bags. The man’s life was saved only by an emergency survival pamphlet hastily retrieved from the bottom of a rucksack. To the surprise of the worried adventurers, now trying to warm the victim (suffering from heat exhaustion-induced shock) by laying across his body, it warned that he must, at all costs, be kept cool.

And then there was the trekker who lasted less than a day had to be escorted back by New Guineans, and the newspaper photographer who had to be taken out by helicopter. “I told them they had to train before they came, but they made their choice and took the chance they could make it. They quickly found they couldn’t. People can be highly resilient, but the Track is unforgiving,” Lynn says.

Lynn may have great faith in the individual’s spirit in times of adversity, but he has little time for much of corporate Australia. He believes Australian business lacks good leadership. He says that since an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report in 1992 which compared our managers with those overseas (and concluded Australian middle management ranked 17 out of 22 in effectiveness; senior management ranked 19), little has changed.

“Some so-called leaders might talk about teamwork and bonding and use all the other buzz-words, but it’s usually just talk,” he says. “Australian employees aren’t stupid; they know that the bosses in today’s climate are looking after number one and that when the crunch comes they’ll be left on their own. In return, they do what they have to do in their jobs and no more.”

Lynn has compiled his own “understandings” to effective management”, which he believes can be achieved from completing the Kokoda Track. These include an understanding of oneself, others, other cultures, the environmental effects of decisions and the sacrifices and achievements of others in history. Over-all, he says, our leadership and teamwork failings result from a lack of adversity in our lives.

Lynn believes adversity should be introduced to Australian business on a planned scale. “We don’t need another war; all you need to do is to take people out of the system and take them back to basics where they can’t hide behind their desks – to get rid of all the crap.‘

COOOO-EEEEE! Five o’clock in the morning and the Kokoda shuffle begins again. The humidity is draining and the washed-out jungle track is little more than a series of irregular steps between tangled tree roots. Then the uphill clambering starts again, followed by a two-hour slide down an almost sheer muddy cliff. By lunchtime, sweating and exhausted, some members of the team are almost broken. Before them is Eora Creek, a raging torrent studded with vicious crags and slippery boulders.

Even with no pack and a rope to hang on to, crossing is hazardous. But the CRA team has to do it the hard way. Like the diggers and fuzzy-wuzzy angels before them in the Kokoda campaign, they have to carry their injured across on a stretcher. Glad for a rest, Dunshea volunteers and the team persuades the guides to put together a stretcher from vines and saplings. Then, slowly, they wade thigh-deep through the icy water. A slip could see them swept away in the pounding water.

They make it. Their teamwork has paid off and no-one is hurt. But the agony is not over yet. In the drenching rain, they manoeuvre the stretcher and its nervous occupant for hour after hour up another mountain turned to slime. Then yet more hours of clambering and slipping through the night towards the next camp.

For some, other tasks were more demanding. Delivering supplies and equipment to villages carrying the whole group’s tents, food and cooking equipment, may have been bearable, but the four mornings of climbing before breakfast, hacking through the jungle to find waterfalls and WW11 aircraft high in the hills, took their toll on badly aching bodies – which still had to survive the track itself.

Gone are the days when the only way to get to adventure camp-grounds was in a beat-up Kombi. These days, Outward Bound even has a 100-feet, three-masted schooner to sail 1,000 corporate clients a year from abseiling to navigating place. But are such courses really effective?

Outward Bound’s business development manager, Ms Kim Niemeier, says “experiential exploration” leadership courses can change people’s attitudes permanently. “You take them to an environment which is totally alien and away from their mobile phones and dress them all up in the same clothes, and they learn to trust the guy at work they thought was a jerk, becau7se he’s on top of the mountain holding the rope.”

Another leader in multi-day leadership training organisations is Perth-based Adventure West. the company trains around 800 businesspeople a year in how to get the best out of themselves and others. It specialises in operating training programs in Australia’s most rugged areas, such as Western Australia’s Kimberley region, as well as in South-East Asia.

A team leader with the company, Mr Colin Hendrie, says the experience often helps people realise the futility of just sitting around discussing things without taking action.

“We had on group of people who sat outside a cave for 36 hours simply trying to decide how to go about exploring it,” he said. “They eventually realised they may not be approaching tasks entirely effectively.”

BRUCE Riley, 54, a successful Sydney businessman, limps into Kokoda village just in front of the CRA team. He is completing his second Kokoda trek with Lynn. For much of this one, he has hobbled up and down mountains with a fractured right ankle. But despite the pain and the almost overwhelming brutality of the track, he believes the experiences have been the most important of his life.

“If you do Kokoda, the there’s nothing else,” he says. “You get tremendous maturation and a wonderful sense of achievement. I feel like nothing is too difficult any more – when things are tough all I have to say is ‘remember Kokoda’ and it all becomes easy.”

The CRA team, now sprawled in the lush grass at the end of the journey, nod their heads in unison. They are all stunned by the beauty of the track. But more than, they made it back alive.

A few weeks after returning from Kokoda, the corporate high-flyer and trained psychologist, Karen Dunshea, is still mulling things over. She believes she has changed but feels it is more “intuitive than cognitive”.

“I can’t really express it in words,” she says. “But practically I’m more patriotic and I have applied some of the teamwork and leadership things we discussed over there, but it’s not just about work; the Kokoda experience applies to general life. It was a really humbling experience to be at the bottom of the pile in physical fitness; I sort of have to come back to a base level; it’s very valuable to be humbled.”