Kokoda Day’ will be a source of immense pride for Papua New Guineans. It has the potential to rival the commemorative status of Anzac Day in Australia. It will provide a strong incentive for Australians to visit PNG for the commemoration and all it represents.

But more importantly it provides a status of recognition for the Papua and New Guinea wartime carriers – the unsung heroes of the Pacific War 1942-1945.

Executive Summary

Over the past decade more than 65,000 Australians, young and old, from all walks of life, have trekked across the Kokoda Trail. They are motivated by the significance of its military heritage and the lure of an adventure in the ‘land of the unexpected’.

The experience has a profound impact on those who complete the pilgrimage.

But more importantly it has exposed them to the vital role Papua and New Guinea indentured carriers played in supporting our troops during our darkest hours of need.

To our great shame their service has never been officially recognised because of their ‘civilian status. It was lost and forgotten during the transition from military to civilian rule of the territories of Papua and New Guinea soon after the war.

Without a regimental unit or union to represent them the only acknowledgment of their service and sacrifice resides in diggers recollections and a poem, ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angel’, written by Sapper Bert Beros whilst convalescing in hospital after being carried safely off the Trail.

As of today, hundreds, perhaps thousands, now lie in lonely, unmarked places across the Owen Stanley Ranges. Their identities are unknown. There is no record of their service. They have no spiritual resting place or Spirit Haus for their families, friends or kinfolk to gather round each year to commemorate their sacrifice. There is no research into who they were? Where they came from? How they died? Or where?

We can begin to rectify this historical anomaly by encouraging Papua New Guinea to dedicate a day to commemorate their service and their sacrifice.

This proposal was first submitted to the PNG National Government in 2008.

It was accepted by the PNG National Executive Council (NEC) in the lead-up to the 70th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2012 however the name was changed to ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angel Day’. According to Dame Carol Kidu MP, a member of the NEC at the time, some MPs from other Provinces claimed ‘Kokoda’ was getting enough publicity, so they changed it to ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angel Day’.

This effectively killed the commemorative and marketing value of the concept as the term ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angel’ is not widely recognised in Australia. Those who are not aware of their service consider it to be somewhat patronising.

It is therefore timely to reconsider the original name in the lead-up to the 80th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2022.

Why Kokoda?

For those who command a desk in far flung bureaucratic empires the care and compassion of a Papuan in a remote jungle is something they will never comprehend.

For those who have been carried to safety on a stretcher over inhospitable terrain the unconditional care of the bearers will never be forgotten.

Soldiers recruited into the Papuan Infantry Battalion in 1942 were issued with uniforms and weapons, trained and served with distinction, were decorated with campaign medals, and marched proudly behind their regimental colours on commemorative occasions such as Anzac Day and Remembrance Day. They were known as ‘green shadows’ because of their mastery of the jungle environment.

Remembrance Day commemorates their first contact against the Japanese army forward of the Kokoda Trail on the 23rd of July each year.

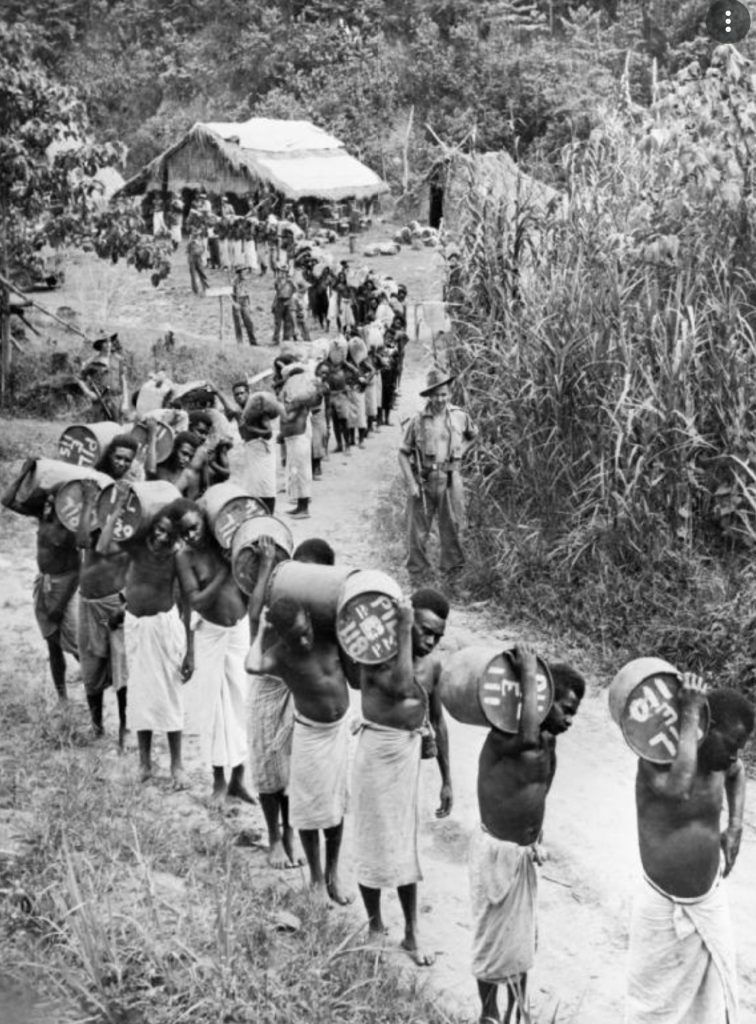

‘Unlike their regimental counterparts, Papua and New Guinea civilian carriers were indentured, often at gunpoint, to support a war they didn’t know about, or understand. They were never issued with a uniform, and never enjoyed the security or esprit de corps of belonging to a regiment. They were essentially fragmented groups of long-forgotten, nameless labourers.’

Their job was to carry supplies forward to our troops. Carrying our wounded back on the return journey was not part of their ‘contract’.But such is their nature of care that, when they came across a soldier who could go no further and faced a certain, anonymous death on the side of a remote muddy track, they would stop, assemble a stretcher from bush materials, load him onto their raw shoulders, and begin a journey that took up to two weeks to complete.

When night fell and temperatures dropped, they would lay each side of their ’white stranger’ and try to keep him warm – sharing the few grams of rice they were rationed, with him.

They were poorly equipped, underfed, often overloaded, and paid a pittance. The spirit of their commitment was captured in a poem by one of their patients who owed his life to their care – Sapper Bert Beros who coined the term ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’.

Many of them now lie in unknown places alongside jungle tracks far from their village homes. They have no grave. They have no spiritual touchpoint. There is no formal remembrance.

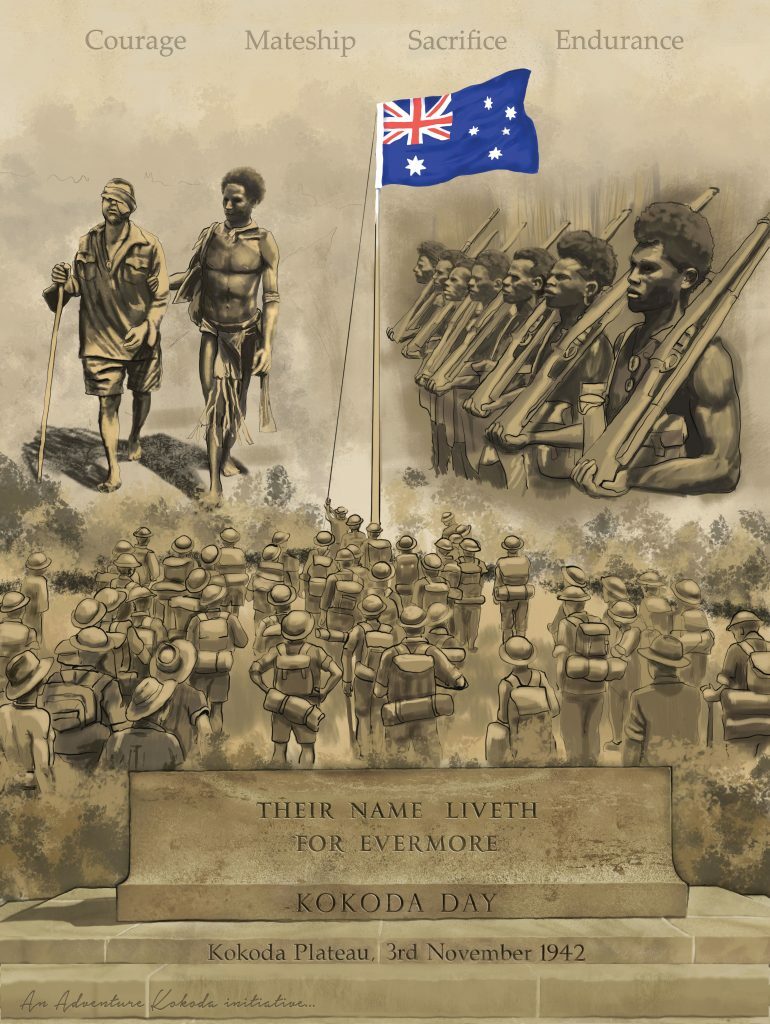

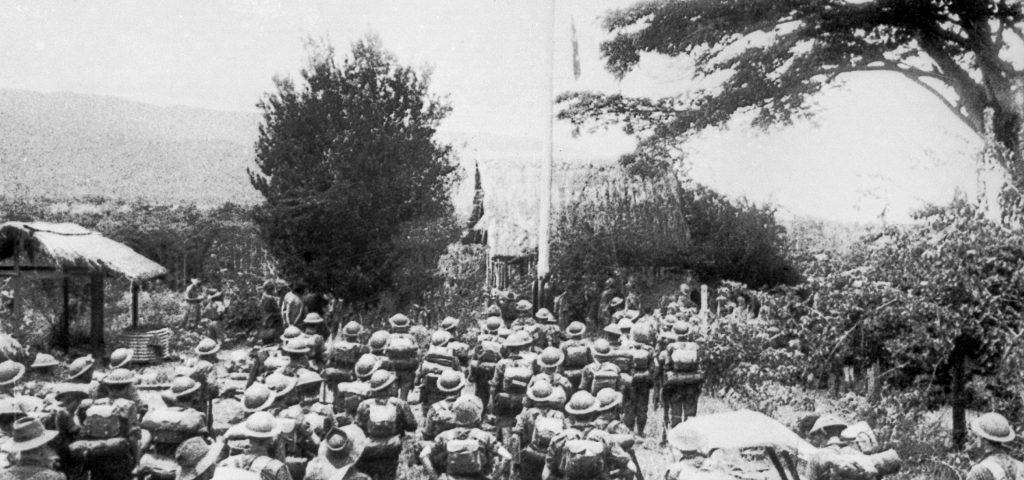

The flag raising ceremony on the Kokoda plateau on 3 November 1942 symbolized the turning of the tide in the Pacific War. This would not have happened without the support of the indentured civilian carriers across the Trail. It also symbolizes the service and sacrifice of indentured civilian carriers in all campaigns throughout Papua and New Guinea from 1942-1945.

‘Kokoda Day’, dedicated to commemorating their service and sacrifice, will ensure their memory is never forgotten.

Australia was unprepared for the war in the Pacific in 1942. Our faith in ‘great and powerful friends’ coming to our aid in the event of Japan entering the war was shattered with the sinking of two British warships near Singapore on 10 December 1941, and a secret deal between UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt for the European theatre of operations to have priority over the South-West Pacific.

The immediate defence of Australia and its mandated territories of Papua and New Guinea was therefore left to untrained militia forces and a small band of New Guinea Rifles as our experienced AIF units were returning from Europe to meet the threat of Japanese invasion.

‘Military manpower resources were so scarce that young Papuans were forcibly recruited from remote mountain villages to support the war effort. They had no understanding of the war, and most were conscripted against their will. They were told that men from Japan were the enemy. But for many of these young men other tribes were also considered ‘enemy’. One can only imagine the fear and uncertainty they felt as they were forcibly marched away from their village clans.’

They were designated as civilian ‘carriers’ but were to become known as ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ because of their selfless sacrifice in assisting wounded and sick diggers during the various campaigns.

They carried vital war supplies on bare shoulders in endless lines over hostile and inhospitable terrain. Today’s Kokoda trekkers are in awe of their strength, endurance, and mastery of their environment. Without this vital link in the chain of our war effort Japan would have been successful in the conquest of Papua and New Guinea.

Australia’s Hour of Need

Today, as we approach the 80th anniversary of the War in Papua and New Guinea, these men are the only link in the chain not to have received any official recognition.

Many claimed not have been properly paid. None were ever issued with a medal. No day has been set aside to commemorate their service or sacrifice. There is no record of who served. They have no touchstone for descendants to commemorate their memory.

The recent upsurge of interest in the Kokoda campaign by Australian trekkers over the past two decades indicates a common desire for the service of wartime carriers to be officially recognised.

The proclamation of a ‘Kokoda Day[i]’ dedicated to their service would be widely welcomed. It would certainly provide an incentive for more Australians to visit Papua New Guinea.

In marketing terms, the name ‘Kokoda’ now shares equal billing with ’Anzac’ whereas ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angel’ is largely unknown and only has emotional appeal to those who have completed the pilgrimage.

Papuan Civilian Carriers

According to the official history of the war in the Pacific[i] the Australian New Guinea Army Unit (ANGAU) was authorised by the Australian government to provide for ‘the conscription of whatever native labour might be required by the Services.’

Under the emergency conditions imposed by the Japanese thrust over the Kokoda Trail, ‘a motley army of native cooks, houseboys, boats crews, rubber tappers, copra boys, carpenters, clerks, medical assistants, and others from the Moresby area were rushed into carrier service and performed magnificently’[ii].

The cost was a 30 percent sick rate and no prospect of release. ‘For four months there was not one rest day for any of them . . . troops could be replaced and relieved because there were reinforcements in reserve, but there never came a time in the whole campaign when there were sufficient labourers or Angau personnel. By October 1942 systemic recruiting in Papua’s southern districts had brought operational carrier numbers up to 1250 on the Kokoda Trail.[iii]

They were paid eight shillings a month – considerably less than the basic the wage of nine pounds, 15 shillings a month paid to an Australian soldier at the time.[iv]

What is not understood by many is that male villagers indentured for work as carriers faced two potential enemies – the invading Japanese, and traditional rival clans whose customary land was foreign to them.

During the period 1944-1957 approximately 2 million pounds was paid by the Australian Government in compensation for property damage to Papua and New Guinea nationals by the Australian Government. In 1975 PNG gained independence and the PNG Government assumed all legal obligations for compensation of its veteran community.

‘Unfortunately, indentured civilian carriers were excluded from benefits under legislation for compensation of nationals who served in the Papuan Infantry Battalion and the Australian New Guinea Army Unit. In 1980 they were also deemed to be ineligible for the Papua and New Guinea War Gratuity Scheme for ex-Servicemen.‘

In 1981 the Australian Government paid $3.25 million to the PNG Government under the Defence (PNG) Retirement Act as a final payment for compensation for indentured civilian carriers. In 1986 the PNG Government introduced payments of PNGK1,000 for each surviving carrier. The payments ceased in 1989 and many carriers claimed to have not received any money.

During the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign the issue of payment and compensation for many of the carriers who claim they were never paid was raised with the Keating Government.

On 21 April 1992, the Australian newspaper reported that returned servicemen in PNG had called on the Australian Government to pay hundreds of local war veterans who helped Australian troops during the Kokoda campaign. According to the report:

“The President of the PNG Returned Services League, Mr Wally Lussick, said Australia had sent about $3.5 million to PNG to help compensate local war veterans in the early 1980s, but much of the money had gone to the wrong people and a large group of carriers missed out. Mr Lussick said much of the money went to those press-ganged into being carriers for the Japanese and many people who took no part in the war received payments. The visit to PNG later this week by the Prime Minister, Mr Keating, for Anzac Day services to mark the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda battles would provide a good opportunity for Australia to make a commitment to the surviving carriers.”

In the PNG Post-Courier of 24 April 1992, the Prime Minister of PNG Prime Minister, Sir Rabbie Namaliu, called on Australia ‘to help compensate WW2 carriers and stretcher bearers”. He raised the issue with Prime Minister Paul Keating at the time. According to the Post-Courier:

“Most of the carriers and ex-servicemen received compensation payments from Australia in the mid-1980s, but many legitimate veterans from the Southern Kokoda Trail near Port Moresby, missed out. PNG authorities estimate up to 200 surviving carriers are still waiting for some kind of payment from Australia for their wartime labour and service. Mr Namaliu said the Government was considering making an approach to Australia to identify and pay those carriers who have gone unrewarded for half a century.”

On 5 May 1992, the Bulletin with Newsweek reported:

Whilst Prime Minister Keating was genuine in his desire to resolve the issue it is now clear that his bureaucracy put it in the ‘too hard basket’ where it has remained.

The argument that ‘it would be inappropriate for the Australian Government to consider taking any further action on this matter in the absence of a detailed proposal from the Papua New Guinea Government’ was a cop-out.

According to Sergeant Ben Moide MBE he and his men in the Papuan Infantry Battalion were ‘nameless warriors:

‘We fought but according to the bulk of the taubadas, we remained nameless; we were just the native scout or the Papuan guide to them. Still, to the gallant few who addressed us by name, I owe them my undying gratitude for treating us as mates. But the fact remains, without the help of all those nameless warriors and carriers who braved the sickness, rain, mud, hunger, despair and enemy of this campaign, all would surely have been lost.’[v]

At the end of the war Sergeant Moide’s unit was awarded a battle honour; he and his fellow Papuan soldiers were issued campaign medals and bravery awards; they have their own national Remembrance Day, and a dedicated Remembrance Park in the national capital.

Their compatriot civilian carriers were never honoured in a similar way. They had no units, no uniforms, no battle honour, no repatriation, and they have no spiritual home. Many lie in unknown jungle areas in Provinces far beyond their traditional village homes.

Digger Tributes

“Keating says compensation cases will be dealt with on their merits and all worthy claims examined; but no concrete sum for individuals has been discussed. The difficulty of maintaining a list of the original carriers is underlined by how few speak English. Family members of dead carriers are calling for posthumous compensation – after all, they took part in a battle that Keating described this week “as more important to Australians than any other battlefield in Europe or Africa.”

In a report on the medical aspects of the fighting withdrawal in the face of overwhelming Japanese forces after the Battle for Isurava was lost, Colonel Kingsley Norris, Assistant Director Medical Services with the 7th Division praised the work of the Australian medics. No living casualty, claimed Norris, was abandoned to the enemy and overall, 750 wounded and sick were shepherded down the track to safety. Norris was also full of praise for the ‘walking wounded’. They had, in Norris’ words, to be treated with ‘absolute ruthlessness’ and not provided with stretchers:

‘Those alone who were quite unable to struggle or stagger along were carried. There was practically never a complaint nor any resentment … One casualty with a two-inch gap in a fractured patella, splintered by a banana leaf, walked for six days …’

Captain ‘Blue Steward, Regimental Officer, 2/16th Battalion:

‘… they never forgot their patients, carrying them as gently as they could, avoiding the jolts and jars of the many ups and downs. The last stretcher was carried out by the Regimental Aid Post boys, two volunteers, Padre Fred and myself. Till then we never knew the effort needed, nor fully appreciated the work the carriers were doing. Their bare, splayed feet gave them a better grip than our cleated boots could claim on the slippery rocks and mud.

‘Some of the bearers disliked the tight, flat canvas surfaces of the regulation army stretchers, off which a man might slide or be tipped.

They felt safer with the deeper beds of their own bush made stretchers – two blankets doubled round two long poles cut from the jungle. Each time we watched them hoist the stretchers from the ground to their shoulders for another stint, we saw their strong leg, arm and back muscles rippling under their glossy black skins. Manly and dignified, they felt proud of their responsibility to the wounded, and rarely faltered. When they laid their charges down for the night they sought level ground on which to build a rough shelter of light poses and leaves. With four men each side of a stretcher, they took it in turns to sleep and to watch, giving each wounded man whatever food, drink or comfort there might be.’

Laurie Howson, 39th Battalion:

‘The days go on. You are trying to survive, shirt torn, arse out of your pants, whiskers a mile long, hungry and a continuous line of stretchers with wounded carried by ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzies’ doing a marvellous job. Some days you carry your boots because there’s no skin on your feet. But when I look around at some of the others – hell! They look crook! Then I have seen the time when you dig a number of holes in the ground and bury your dead. Nothing would be said, but you think ‘maybe it will be my turn next.’

Private Geoffrey Hamilton-Smith:

‘At Templeton’s Crossing it may well be imagined what we struck; for every half hour had been bringing us nearer to the front . . . it was a little beyond here, at the junction of the Cargi and Myola tracks, that we came in contact at last with living fighters, after the long series of death scenes. Some of our soldiers were coming back from the forward lines for rations. They told us of fierce fighting a couple of hours onward, and in their wake came a procession such as I had never seen in my life before, and which moved me to the depths. Picking their way very carefully with expressions of solemn responsibility, came native bearers with the badly wounded. Some of those forms under their coverings were horribly mutilated and might not survive the long, perilous journey back to the base hospital from the R.A.P. Others were straight and very still.

‘Some were in an agony of suffering in spite of all that had been done to mitigate and soothe. The natives moved softly and silently, handling the stretchers with a surprising deftness in rough places in order to save their human burden from the slightest jolt. Their black faces were soft with pity and concern. They would carry those poor fellows along such a route as I have described, through mud and slush and morass, along the razor backs, quickly and softly over the fields of death and pestilence, till they arrived at their intended destination. Some of the sufferers would fall into natural sleep soothed by the rhythm of the lithe movements, and oblivious of the wildness and perils of the way.’

Papua New Guinea – Remembrance

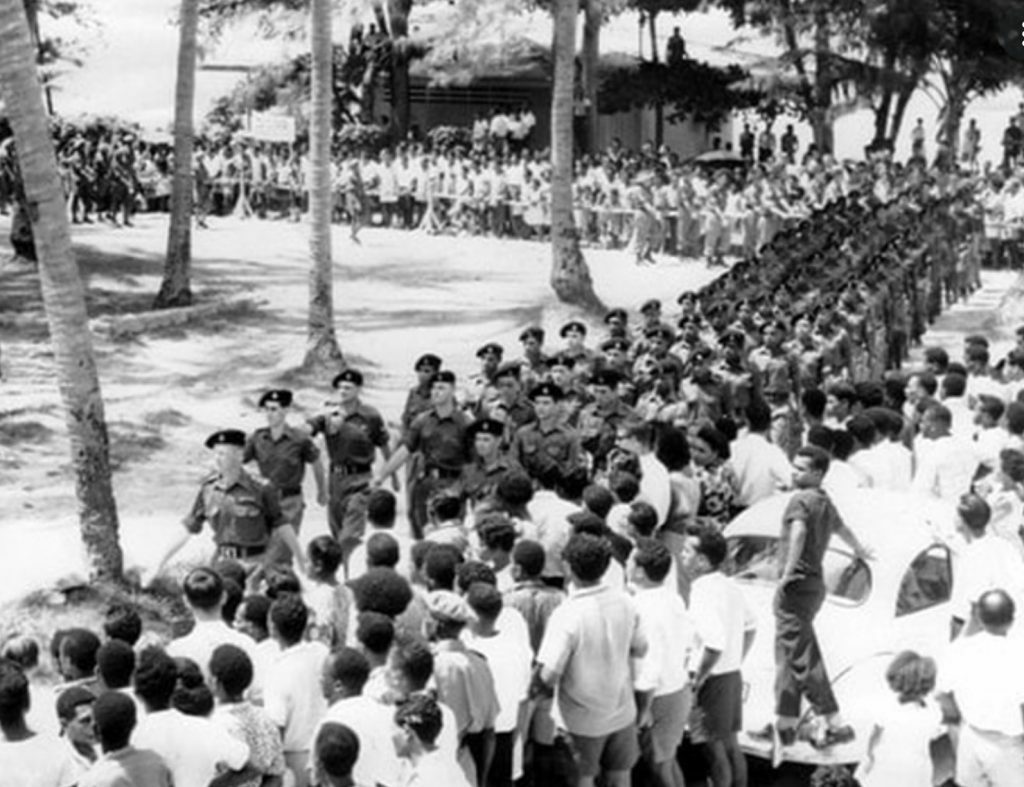

According to ANU Professor, Hank Nelson, there was a significant change on the Anzac march in Port Moresby in the late 1960s. As the parade came along Port Moresby’s Ela Beach Road, several of the senior white ex-servicemen who, by rank or unit, usually led the march, dropped back to join the Papua and New Guinean ex-servicemen. From then, the marches were integrated with Australians, Papua and New Guinean ex-servicemen marching side-by-side[i].

Nelson reported that after 1975, ‘it was thought inappropriate that an independent Papua New Guinea retain Anzac Day as a national holiday.

The landing on the beaches of Gallipoli, the references to Johnny Turk, and the Australians’ celebration of the birth of a nation, had no relevance to Papua New Guineans. Although 25 April became an ordinary working day, the dawn service, the gunfire breakfast and other ceremonies continued. On significant anniversaries, such as the 50th anniversary of Kokoda in 1992 when the Australian Prime Minister, Paul Keating, was present, these were still important international occasions. On Anzac Day 1992, just one group of trekkers led by Major Charlie Lynn[ii] had timed their walk from Kokoda to be at Bomana for the dawn service.’[iii]

Searching for an appropriate date on which Papua New Guineans might remember the war, the new government chose 15 August, the day on which the war against Japan ended. But this was a day with as much significance in capitals from Tokyo to Singapore and Washington as in Port Moresby, and there was no special part played by Papua and New Guineans to secure peace. Papua New Guinean ex-servicemen did not like it: a day that celebrated peace had little time for remembering battles, tributes to old comrades, and a march behind a military band. Accepting that generating public interest was always going to be difficult.

In 1982 the government decided that the public holiday for Remembrance Day would be shifted to 23 July to commemorate the first action of the Papuan Infantry Battalion against the Japanese forward of Kokoda. Unfortunately the day has little resonance as it was ‘a minor encounter; there were few casualties and perhaps none among the Papuan soldiers; the fighting was confused rather than heroic; and it was given slight significance at the time or in later histories’.[iv]

In Papua New Guinea, leaders continued to make statements about their fellow citizens taking a holiday on 23 July, but few knowing why.

At the end of 2004, the Papua New Guinea government declared that in future Anzac Day would again be a public holiday. That was recognition of the extent to which Anzac Day had become associated with memories of war through the years of Australian rule and since, and an admission that specific Papua New Guinean experiences and ways of remembering are yet to supplant Australian. At the same time, Remembrance Day on the 23 July has remained a public holiday; debate continues about the form and content of public remembrance ceremonies; and on the eve of Remembrance Day 2006 a journalist ‘bemoaned the heroics of our own people during WWII which were never told or recorded’.[v]

In 2008 Governor-General Paulias Matane paid tribute to soldiers who fought in the Pacific War and Bougainville and added:

“Also, we must remember those who provided intelligence reports, Coastwatchers and the fuzzy wuzzy angels. All these fallen heroes contributed in a significant way to the strategic defence of our land then and today.”

The reference to ‘fallen heroes’ seems to have been an afterthought by the Governor-General as their memory has been relegated to random mentions of their deeds at various services rather than formal inclusion along with a day dedicated to their memory each year.

It’s the least we can as we move towards the do 80th anniversary of the war in Papua and New Guinea.

So how do we remember them?

Commemoration of their service in perpetuity is best achieved through the formal dedication of a day to their service, the creation of touchstone symbols such as a traditional cenotaph (Spirit Haus) in, or adjacent to, Bomana War Cemetery, and the inclusion of a wartime carrier segment in Anzac Dawn Services.

The proclamation of ‘Kokoda Day’ in the lead up to the 80th anniversary of the raising of the Australian flag at Kokoda would resonate throughout Papua New Guinea and Australia due to the symbolism of the occasion.

General George Vasey was well aware of this symbolism when he paraded the depleted ranks of his two Australian brigades paraded on the Kokoda plateau to raise the Australian flag on the 3rd November 1942. It was the culmination of one of the most desperate jungle campaigns ever fought on our doorstep against all the odds with little more than rifle, grenade, bayonet, fist, and courage.

An army stretcher-bearer, Private Geoffrey Hamlyn-Harris captured the moment in his diary:

‘As we marched in and took up our position for the ceremony, we could all feel in our bones that history was being made. The Australian flag was raised, with soldiers and natives as solemn witnesses. Tribute was paid to all who had died along the track for the victory which had taken place here, making this beautiful valley and its air strip ours once more, and clearing the way for what all of us now felt must be a successful issue.

‘Although I find it hard to express precisely what I mean, I felt that the raising of the flag here, as elsewhere in New Guinea where the boys were overcoming the enemies of civilisation, heralded a new epoch of Aussie history. Considering what was accomplished collaboratively in a war such as had never been known in the world before, what might not we do together in a voluntary way for the Age of Peace to follow? The thing could be ideal, you see, everybody working as one man for a new and better method of world government which would benefit all equally.‘

The faces of the witnesses standing around the flag pole in the centre of the village were a living, though silent, testimony of what had been suffered for Australia and for moments like this, by the lads of the graves up the range and all along the track by which we had come. We were thinking individually of those pals of ours; for the Owen Stanley Range still overshadowed us in memory as well as in fact, an unpleasant monster conquered; and only those who had shared their experience could have understood the extent of the price they paid in advance for victory.’

As the flag was raised on the plateau there was a conspicuous silence among the troops. Their thoughts were with their mates who didn’t make it. More than 600 left lying-in shallow graves back along the Trail. Little did they know that hundreds more from the ranks assembled in front of the flag would be dead within the next few weeks because worse was yet to come in the battle of the beachheads at Buna, Gona, and Sanananda.

Kokoda Day

Kokoda Day provides an opportunity for PNG to create their own national remembrance day in accordance with Commonwealth tradition. It will include:

Flag Raising Re-enactment on the Kokoda Plateau

The centrepiece of Kokoda Day would be an annual flag-raising re-enactment on the Kokoda Plateau with traditional dancing and singing by Orokaiva cultural groups. In the afternoon Koiari and Orokaiva Rugby League teams would compete for the annual Kokoda Cup on the Kokoda Plateau.

Kokoda Day would attract Australian veterans’ groups and many others who would not otherwise visit the area due to their inability to trek. This would then lead to visits extending to the beach-head battles of Buna and Gona due to the recent upgrade of Popondetta airport and the new bridges across the Kumusi River.

The Kokoda trekking season, which comes to a close in October, would be extended for a month to include the Kokoda Day Service.

PNG Kokoda Day School Services

Education is a key building block for national pride.

Wartime carriers were indentured from all over Papua and New Guinea to support the war effort along the Kokoda Trail, the Huon Peninsula, the Markham–Ramu Valley and Shaggy Ridge.

A Kokoda Day Flag Raising Service in schools throughout PNG at assembly on 3rd November, supported by an appropriate educational package, would be a key component in the further development of national pride in PNG.

The increasing number of PNG students at the Bomana Anzac Dawn Service each year is indicative of a desire for them to learn more about our shared wartime history.

PNG writers, poets and playwriters could be engaged to tell the story of the Papuan Infantry Battalion and their wartime carriers. Rashmii Bell’s recent publication ‘Roses at Eora Creek’ is a splendid example of what can be achieved in this regard.

Kokoda Scholarships

Kokoda Scholarships to honour the legacy of our war dead through the establishment of perpetual scholarships in their name at Bomana, Lae and Rabaul (Bita Parka) war cemeteries would ensure Rudyard Kipling’s quote ‘Their Names Shall Liveth for Evermore’ engraved on each Stone of Remembrance would be honoured in perpetuity.

This link contains a concept for a Kokoda Scholarship Program which would be largely funded by trekkers who would like to leave a footprint behind after their pilgrimage.

Cenotaph (Spirit Haus)

Cenotaph is a Greek term for an empty tomb, a sepulchral monument in honour of a person whose body is elsewhere.

In Australia war memorials have special significance, as they often represented ‘surrogate graves’ for soldiers whose bodies were buried in overseas war cemeteries or could not be located. Usually erected in prominent civic areas such as town squares, parks, central intersections, or near public schools, these local monuments continue to be a focus for community Anzac Day services.

Papuan soldiers and indentured civilian carriers who now lie in remote, unmarked graves currently have no spiritual resting place. The inclusion of a Spirit Haus within, or adjacent, to our war cemeteries in PNG would provide a national focus for commemoration services on Anzac Day, Remembrance Day, and Kokoda Day. Each Province in PNG would be encouraged to develop a similar Spirit Haus which represents their cultural beliefs.

PNG Anzac Dawn Service

The annual Anzac Dawn Service is conducted by the Port Moresby RSL Sub-Branch which does a commendable job.

These follow the script of the traditional Australian Dawn Service. ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angels’ are given honourary mention but their remembrance is not included in the format of the service.

PNG dignitaries along with an increasing number of PNG families attend these solemn services each year. Consideration should now be given to including a commemorative segment involving a re-enactment by PNG students acting as stretcher bearers.

Students in traditional dress would assemble in rows to the rear of the Stone of Remembrance in the Anzac pre-dawn darkness.

As the first glint of sunlight strikes the polished granite headstones, they would raise stretchers onto their shoulders and walk silently through the uniform rows of our war dead to the muffled beat of traditional kundu drums. This will symbolise the linkage of their spirits.

On arrival at a designated area at the base of the Cross of Sacrifice they would lay their stretchers down, turn inwards, and bow their heads where they would remain as a traditional ‘catafalque party ’ for the duration of the service.

The inclusion of this segment would attract national media coverage throughout Australia and PNG.

Kokoda Day Fundraising Campaign

A national fundraising campaign will be co-ordinated with Network Kokoda who will aim to enlist the support of the 54,623 Australians who have trekked Kokoda over the past decade. These include the CEOs of some of Australia’s most successful companies.

RSL sub-branches and clubs will be invited to host ‘Kokoda Day’ dinners.

Schools will be invited to host a Kokoda Day service and encourage student to make a gold-coin donation for their PNG brothers and sisters.

A national ‘Kokoda Route March’, based on the traditional 20-mile army route march, will be introduced.

Marketing Value of Kokoda for PNG

The term ‘Kokoda’ now has a resonance equal to ‘Anzac’ in marketing terms. The fact that more than 54,623 Australians have trekked across the trail over the past decade is testimony to this fact.

There are many thousands more who would make a pilgrimage to Kokoda without having to trek because of the age and/or physical condition. All they need is the opportunity to plan and commit to it.

‘Kokoda Day’ will provide that opportunity.

Summary

The Australian army would have been defeated in the Kokoda campaign if they had not received vital logistic support from the indentured civilian carriers. Hundreds would have died of their wounds and tropical illnesses if they had not been carried off the Trail.

These indentured carriers have never been officially recognised. The Australian government specifically excluded them from benefits under legislation for compensation of PNG nationals who served in the Defence Force. In 1980 they were also deemed to be ineligible for the PNG War Gratuity Scheme for ex-Servicemen.

The service of the indentured carriers, and the sacrifices they made towards the allied victories in Papua and New Guinea, should be honoured and enshrined in a special day dedicated to their memory.

The most appropriate day is November 3 as the Australian flag would never have been raised on the Kokoda plateau if it had not been for their service.

Young Papua New Guineans are becoming more aware, and increasingly proud of their wartime heritage. Thought should be given to the creation of a traditional cenotaph in the National capital at, or adjacent to, Bomana War Cemetery – a spiritual tomb for those who never returned to their village. The form and location of such a significant national structure would be the subject of a separate resolution by the PNG Government.

Kokoda Day – Kokoda Track Memorial Walkway, Concord, Sydney

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner Education Centre, Kokoda Track Memorial Walkway, Concord

Audio visual presentation of the Kokoda Trail – Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner Education Centre, Kokoda Track Memorial Walkway

Increasing numbers of prominent Australians trekking Kokoda – including Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Federal and State MPs, media personalities, business executives, and students – are reconnecting with the ‘grandsons of the fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ and would agree that we have to do more to commemorate their contribution to our victory in the jungles of Papua and New Guinea.

[i] The Journal of Pacific History. Kokoda: and two national histories. Hank Nelson

[ii] The group was led by Major Charlie Lynn, a retired Australian army officer.

[iii] [iii] The Journal of Pacific History. Kokoda: and two national histories. Hank Nelson

[iv] Australia in the War of 1939-1945: South West Pacific Area-first year Kokoda to Wau P124-5

[v] The National. Jack Metta. 21 July 2006

[i] Australia in the War 1939-1945, p116. Dudley McCarthy

[ii] Blamey quoted by Powell in ‘War by Stealth’ p113.

[iii] [iii] The Third Force. ANGAU’s New Guinea War, 1942-66. Alan Powell, Oxford University Press. P196

[iv] The Third Force. ANGAU’s New Guinea War, 1942-66. Alan Powell, Oxford University Press. P192

[v] Nameless Warriors – The Ben Moide Story. Lahui Ako. Sterling Publishers. 2012.

[i] An earlier proposal to proclaim Kokoda Day on 3rd November to commemorate the raising of the Australian flag at Kokoda was approved by the National Executive Council however the name was changed to ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angel Day’ in the process. This decision defeated the purpose of the announcement as most contemporary Australians know nothing about ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ until they have visited Papua New Guinea. Many regard it as a patronising term.