‘Kokoda is almost the complete adventure experience for Australian baby-boomers and young adventurers. It requires physical stamina and mental tenacity. The wartime history evokes strong emotions. The unconditional care and support of local PNG guides and villagers is humbling. The environment is rugged, remote and pristine.’

Wartime tourism is unique because it unites people who were once divided. It provides an avenue for the establishment of empathetic relationships between trekkers and tourists of various nationalities and subsistence villagers who the guardians of sites sacred to Australia, the United States and Japan.

The potential of the Kokoda trekking industry and the benefits that will accrue to local villagers along the trail is currently limited by the lack of a professional management authority supported by appropriate legislation.

The potential of a wartime tourism industry is limited by an effective strategy supported by an appropriate organisational structure.

If we procrastinate and allow such sacred land to be lost to other emerging economic opportunities in PNG (mining, forestry, farming) subsequent generations will never forgive us.

If we allow the industry to continue as it has over the past decade the only growth industry will be conflict management.

But if we use the lessons we have learned since the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign that put ‘Kokoda’ back on the radar we will be only limited by the imagination of current and future generations who seek to walk in their footsteps.

The most relevant guide to the potential of a wartime tourism industry in PNG is the increasing interest in the Australian War Memorial and the continued growth in the number of Australians making the pilgrimage to Gallipoli.

In 2017 1.2 million people visited the Australian War Memorial – this included 145,927 school children. Media coverage extended to 24.4 million people on Anzac Day – 38,000 attended the Dawn Service. Their website recorded 5.6 million visits and they have 100,000 followers on Facebook.

Each year up to 9,000 Australians visit the Dawn Service at Anzac Cove. Thousands more visit it at other times of the year. It is now becoming a pilgrimage for more than a million Turkish people also visiting Gallipoli each year.

It is worth noting that PNG is closer, safer, cheaper and more significant to the current and future generations of Australians because ‘at Gallipoli we fought for Britain and lost – at Kokoda we fought for Australia and won!’

Two of the key objectives we wished to achieve when we proposed the establishment of a management authority for the Kokoda Trail in 2002 were:

- To establish ‘Kokoda’ as a model for a wartime tourism industry in PNG; and

- To ensure villagers along the trail received shared benefits from the emerging Kokoda trekking industry.

Papua New Guinea has the potential to be a world class ‘adventure-tourism’ destination but it has to address negative perceptions in regard to safety and reliability – particularly after the ‘Black Cat Track’ murders. This will require a focused investment in national marketing and support for the development of niche adventures such as wartime pilgrimages, eco-trekking, white-water rafting, caving, diving, surfing, game-fishing, bird-watching, and culture.

People who participate in these niche adventure activities are generally more aware of the sensitivities of culture and environment and do not expect 5-star accommodation and service. They are also more tolerant of ‘surprises’ that are often experienced in the ‘land of the unexpected’.

Recent interest in wartime tourism indicates that it has significant potential as a niche industry for PNG tourism. This is evident in the rapid increase in the number of trekkers since the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 1992.

‘Kokoda’ is almost the complete adventure experience for Australian baby-boomers and young adventurers. It requires physical stamina and mental tenacity. The wartime history evokes strong emotions. The unconditional care and support of local PNG guides and villagers is humbling. The environment is rugged, remote and pristine.

Many trekkers have invited their PNG guides to Australia to meet families and friends after they return. Many more are willing to contribute to agricultural, health and education initiatives to assist local villages as demonstrated in the attached report.

Beyond Kokoda are wartime adventures in Rabaul, Milne Bay, Buna, Gona, Salamaua, Nadzab, Lae, Finchafen, the Finisterre Ranges, Death Valley, Shaggy Ridge, Madang and Wewak. These are not only different battlesites – they are inhabited by different cultures with different traditions that create an adventurous smorgasbord.

Wartime tourism is not restricted to trekkers. It has the capacity for wartime cruises to Port Moresby, Milne Bay, Lae, Madang, Wewak, Aitape, Manus, Rabaul, Bougainville and the Solomon’s. Imagine an Anzac Dawn Service at Owers Corner; a showcase of PNG culture along Ela Beach; a ‘Beating-of-the-Retreat’ at Bomana War Cemetery followed by a 7-day Pacific War Cruise to each of the significant coastal/island battlesites.

The most important challenge for PNG is to develop a sustainable model that can be applied to each area. The development of the Kokoda trekking industry provides a timely opportunity for a case study as the basis for developing a model for wartime tourism.

Factors

The following factors should be considered in the development of an effective marketing strategy for the Kokoda Trail.

- ‘Kokoda Trail’ is the name of the Battle Honour awarded to the Papuan Infantry Battalion by the Commonwealth Battles Nomenclature Committee in 1953.

- ‘Kokoda Trail’ is the name recommended by the PNG Geographical Place Names Committee, adopted, and gazetted by the PNG Government in 1972.

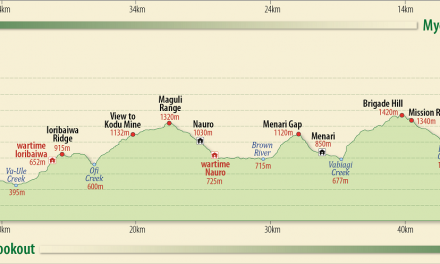

- The Kokoda Trail is a 138 km trek across the Owen Stanley Ranges between Owers Corner and Kokoda. It’s not a Kokoda ‘Track’ and it’s not 96 km!

- The Kokoda campaign was a series of battles fought across the trail during the period 29 July – 3 November 1942.

- The Kokoda Track Authority (KTA) was proclaimed in 2004. Warren Bartlett was appointed CEO on a PNG salary of K25,000. A part-time assistant was engaged to assist him.

- During the period 2004 – 2008 trekker numbers increased by 255% from 1584 to 5621.

- In 2009 the Australian Department of Environment assumed control of the Kokoda trekking industry. Rod Hillman was appointed CEO on a salary package of more than half-a-million kina. Staff increased 10-fold and a multi-million budget was allocated.

- During Hillman’s tenure as CEO from 2009 – 2012 trekker numbers declined by 36% from 5621 to 3597.

- Hillman’s ‘CEO designate’, James Enage, was appointed CEO in 2013 on a much reduced salary. During Enage’s tenure from 2013 – 2018 trekker numbers declined by a further 16% from 3597 to 3033.

- During the period 2009 – 2018 there has been a 46% decline in trekker numbers from 5621 to 3033. The decline has resulted in a loss of K34 million in tourism revenue for PNG; a loss of 70,000 working days for PNG guides and carriers; and a loss of K1 million for campsite owners along the trail.

- The decline in trekker numbers is due to a combination of factors. An air-crash in 2009 saw numbers decline by 33% over the following two years 4364 to 2914.

- The 70th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2012 saw trekker numbers increase by 23% from 2914 to 3597. This was largely attributed to a successful marketing campaign by Air Niugini – a map of the Kokoda Trail was painted on one of their aircraft; a centrefold feature was published in the Weekend Australian; and John Williamson was engaged to sing at the 75th anniversary Dawn Service.

- Rod Hillman departed as CEO without leaving a single management protocol in place. No legislation had been developed. No village workshops had been conducted. There was not a single toilet along the entire trail that met the most basic of hygiene standards.

- James Enage inherited a completely dysfunctional system that saw trekker numbers decline by 28% from 3597 to 2597 over the next two years following Hillman’s departure.

- During the 75th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2017 there was a 22% increase in trekker numbers from 2597 to 3173.

- Management problems and trek closures saw a decline of 4% from 3173 to 3033 in 2018.

- The increase in trekker numbers during significant anniversary years (37% increase for the 65th anniversary in 2007; 23% increase for the 70th anniversary in 2012; 22% increase for the 75th anniversary in 2017) indicates that the military heritage of the Kokoda campaign is the primary reason Australians of all ages want to trek across the Kokoda Trail.

- According to TripAdvisor the Kokoda Trail is PNGs premier tourism destination despite the 46% decline in trekker numbers since the Australian Government assumed control of the Kokoda trekking industry in 2009.

- After a decade in-situ and the expenditure of more than $50 million by the Australian Government there is no Master Plan to honour, protect and interpret our shared wartime heritage across the Kokoda Trail. The potential of the Kokoda trekking industry will not be realised until such a plan is developed by an accredited military heritage architect.

The Kokoda Trekking Industry

- According to the KTA website there are 37 licensed trek operators.

- A lack of integrity in the licensing system resulted in 15 unlicensed trek operators leading treks across the trail in 2018 while 20 licensed operators did not take a single trekker.

- There is no incentive for licensed trek operators to invest in the industry due to the lack of integrity in the licensing system and the lack of management of peak trekking periods.

- Peak periods occur during the Anzac and school holiday periods.

- There is no protection for the welfare of PNG guides and carriers engaged by trek operators.

- There are no protocols to ensure campsite owners are paid the recommended fees.

- There is no effective ranger system.

- There is no campsite booking system.

- There is no campsite development system

- There is no trek itinerary management system.

- There is no database.

Media

Media interest in Kokoda started when former Prime Minister, Paul Keating attended the 50th anniversary Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery in 1992. He was the first Prime Minister to visit Kokoda since the war.

Four years later Channel 9 screened a documentary with a group of celebrities led by Angry Anderson. The program attracted almost 3 million viewers and was the highest rating Current Affair show for many years.

On the 60th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign former Prime Ministers, John Howard and Sir Michael Somare opened a memorial at the Isurava battlesite. This attracted nationwide publicity.

During this period all major newspapers and magazines ran major feature articles on the Kokoda campaign and the stories of trekkers as more and more sought the challenge of walking in the footsteps of the brave.

As a result of comprehensive media coverage between 1992 and 20012 (the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the campaign) the name ‘Kokoda’ is now as familiar as ‘Anzac’.

Marketing Strategy

The most effective strategy beyond 2018 is to focus on two national days of commemoration i.e. Anzac Day and Kokoda Day.

| ANZAC DAY Anzac Day commemorates the landing of our Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. The day now commemorates all armed conflicts since then. The annual Anzac Dawn service at Bomana War Cemetery is well organised by the Port Moresby RSL and attracts a large crowd with an increasing number of Papua New Guineans over recent years. Consideration should be given to developing the Anzac Dawn Service as a joint RSL-PNG service through the inclusion of a PNG commemorative segment and the development of a ‘Spirit Haus’ as a cenotaph[i]. Until now there has never been any formal recognition of the wartime carriers, affectionally known as ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ – no honour roll, no certificate, and no medal! Whilst they were not enlisted servicemen they were conscripted and served at the front. There was no difference between an army stretcher bearer and a native stretcher bearer on the Kokoda Trail – they faced the same conditions and the same risks. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of them now lay in lonely unmarked places across the Owen Stanley Ranges. Their identities are unknown. There is no Honour Roll to record their service. They have no spiritual resting place or Spirit Haus for their families, friends or kinfolk to gather round each year to commemorate their sacrifice. There is no research into who they were? Where they came from? How they died? Or where? We can begin to rectify this historical anomaly by including a commemorative segment in our Anzac Dawn Service and engaging a heritage architect to design an appropriate ‘Spirit Haus’. A commemorative segment would involve a re-enactment by PNG students acting as stretcher bearers. They would assemble along the front of the headstones to the rear of the Stone of Remembrance in the pre-dawn darkness. At the first glint of sunlight strikes the white granite headstones in the pre-dawn darkness they would raise their stretchers onto their young shoulders and walk silently past the granite headstones towards the Cross of Sacrifice to the solemn beat of traditional kundu drums. This would symbolise the passing of their spirits through those they tried to save. On arrival in a designated area near the Cross of Sacrifice they would lay their stretchers down, turn inwards and bow their heads where they would remain as a ‘catafalque party’ for the duration of the service. The inclusion of this segment would attract national media coverage in Australia and PNG. Spirit Haus The inclusion of a ‘Spirit Haus’ as a cenotaph within the small vacant area to the rear of the Guest Register (approximately 20m X 20m) would provide a spiritual resting place for the wartime carriers whose remains have never been found. The Spirit Haus would be protected by PNG guards in traditional costumes who would tell the story of the wartime carriers and recite the poem ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angels’ by Sapper Bert Beros on request. It would soon become a magnet for tourists and photographers. Considerations The increasing threat of terrorism at Gallipoli will deter many Australians from visiting the area. As a result we can expect increasing numbers to visit the Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery each year. Papua was Australian territory at the time of the War in the Pacific. It was therefore the only time that Australians have defended their own territory against an invading army. Our fighting elements included Australian army, navy and air force units, the Australian New Guinea Army Unit, the Papuan Infantry Battalion, coast-watchers and wartime carriers. All except the wartime carriers have been officially recognised. The inclusion of a commemorative segment and a ‘Spirit Haus’ at the Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana would close the loop on those we commemorate and would be a great source of pride for PNG citizens that would contribute to the principle of Commemoration in Perpetuity. |

| KOKODA DAY On 3 November 1942 the Australian flag was raised on the Kokoda plateau after a desperate jungle war fought across the Owen Stanley Ranges. It represented the turning of the tide in the war against Japan. Australia was unprepared for the war in the Pacific in 1942. Our faith in ‘great and powerful friends’ coming to our aid in the event of Japan entering the war was shattered with the fall of Singapore in December 1941 – and the secret deal struck between Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt give priority support to the United Kingdom at the expense of Australia and the South West Pacific. The defence of Australia and its territories of Papua and New Guinea were thus dependent on untrained militia forces and a small band of New Guinea Rifles as our experienced AIF units were returning from Europe and the Middle East to meet the new threat. Resources were so scarce in New Guinea that young Papua and New Guinea men in remote mountain villages were forcibly recruited to support the war effort. Many had no understanding of the war and were conscripted against their will. They were told that men from Japan were their enemy. For many of these men other villagers living in remote tribal lands were also considered ‘enemy’. One can only imagine the fear and uncertainty they felt as they were forcibly marched away from their families and clans. They were designated as Carriers but were to become known as ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ because of their selfless sacrifice in assisting wounded and sick diggers during the various campaigns. They carried vital war supplies on their bare shoulders in endless lines over hostile and inhospitable terrain. Modern day trekkers are in awe of their efforts. Without this vital link in the chain of our war effort Japan would have been successful in their conquest of New Guinea. Today, 76 years after the Pacific War, they are the only link in the remembrance chain not to have received any official recognition. Many claim they were not properly paid. None were ever issued with a medal. No day has been set aside to commemorate their service or sacrifice. No Roll of Honour has been prepared to record their names. The recent upsurge in interest in the Kokoda campaign by Australian trekkers indicates there is a strong desire for our wartime links with Papua New Guinea to be recognised. This can be achieved by providing them with an incentive to visit, or revisit the country. The proclamation of ‘Kokoda Day’ on the anniversary of the day our Australian flag was raised on the Kokoda plateau would be a fitting tribute to their service and sacrifice. Kokoda Day would involve a re-enactment of the flag raising each year. It would include a sing-sing with traditional Orokaiva dance groups and an annual rugby league match between the Koiari and Orokaiva in the afternoon. A ‘Kokoda Day’ flag raising ceremony would also be held in every school in PNG to inform students of the contribution their forefathers made in defence of Papua and New Guinea from 1942-1945. A sunset ‘Beating of the Retreat’ service could be held at Bomana War Cemetery. The Kokoda Day Flag Raising Re-Enactment would attract national television coverage throughout Australian and PNG as well as newspaper articles on the historical significance of the day. It would be the main topic on social media sites. |

Owers Corner

Owers Corner has the potential to become the most visited tourism destination in Papua New Guinea because of its wartime historical significance; its road access to the nation’s capital; and its access to electricity.

The precinct could include a replica village featuring Koiari tree-houses; a granite memorial wall with famous images from the Kokoda campaign; interactive stations with maps for each of the battle-sites along the trail; interpretive panels, stalls for local landowners and an outside theatre for the performance of traditional dances.

It could include a Visitor’s Centre based on the design of the Indigenous Centre at Mossman Gorge.

Such a development would also see the establishment of a sustainable day-trekking industry with short guided treks down to the Goldie River and/or up to Imita Ridge and back.

The economic future of the Owers Corner community would be assured with such a development.

Social Media

The development of a professional website supported by a database and active social media campaign is an essential tool for modern marketing.

The website should have provision for relevant documentaries on the Kokoda campaign; an active blog; informative newsletters; trekker surveys; a database; and links to other adventure activities in PNG.

Accurate information and maps should be provided to Google, Wikipedia, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Instagram, and Lonely Planet.

Regular e-newsletters should be distributed to the Australian War Memorial, the RSL, Battalion Associations, the Australian – PNG Business Council, Education Departments, schools/colleges/universities and traditional media organisations.

Trekker Needs

There needs to be recognition that trekkers are paying customers/clients. It is therefore essential that their needs be identified and met. Without them there is no industry; no benefits; and no future for remote villagers apart from the scourge of welfare/aid dependency.

In the first instance trekkers are not motivated to trek Kokoda in search of an ‘environmental levitation’ or a ‘cultural awakening’ – they are motivated by the physical challenge of walking in the footsteps of our diggers and learning about the wartime history of the Kokoda campaign. An appreciation of the pristine environment of the Owen Stanley Ranges; the culture of the Koiari and Orokaiva villagers who live along the trail; and an awareness of the opportunities for adventure travel in PNG are outcomes of their Kokoda experience.

In essence trekkers’ needs are basic – they want to be safe; they want to be informed; they want to experience the natural environment and traditional culture; they want to maintain a discreet integrity within their trek groups; and they want clean ablution facilities.

Landowner/Community Needs

Traditional owners of land sacred to our shared wartime heritage must be the major shareholders in the Kokoda trekking industry. They must be consulted on a continuous basis; they must receive their fair share of economic and social benefits; they must be engaged in value-adding opportunities; and they must be assured of a sustainable economic future for their children and their local communities.

Conclusion

Trekker statistics indicate that PNG Tourism has a clear choice for the Kokoda trekking industry.

It can continue to operate as a 3rd World destination with 4th World management systems and campsite facilities or it can develop a strategy to become the wartime destination of choice for 1st World trekkers.

It’s not about money – Kokoda is already sustainable. It’s not about meetings, forums and workshops – nothing has been achieved from these for more than a decade. It’s about leadership, decision-making and commitment.

If it’s to be – it’s up to PNG.

Charlie Lynn OAM OL

22 December 2018

[i] The word cenotaph is derived from the Greek kenos taphos, meaning “empty tomb.” A cenotaph is a monument, sometimes in the form of a tomb, to a person or group of persons buried elsewhere.