First published for the 70th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2012

Michael Pender, an accredited Military Heritage Architect from HPA Projects was commissioned by Network Kokoda to develop a Master Plan for the Kokoda Trail for the 70th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2012.

The plan has been ignored by the DFAT Kokoda Initiative in PNG as they regarded the development of a World Heritage Listing for the Owen Stanley Ranges as a priority.

Since then, a 2015 report from an Australian expert on World Heritage listings, Dr Peter Hitchcock AM and Dr Jennifer Gabriel concluded that the Kokoda Trail does not meet the criteria for a World Heritage listing.

A copy of their report: ‘World Heritage, Tentative Listed Sites in Papua New Guinea-Report on a Review of the Sites’ can be viewed on this link’.

The plan was ignored again for the 75th anniversary – and again for the 80th anniversary!

- The Kokoda Trail is an important heritage site for both Australia and Papua New Guinea.

- The heritage values of the Kokoda Trail are unique and in evidence.

- As custodian, Papua New Guinea is not able to protect or manage the heritage.

- The Kokoda Initiative cites tourism as a key driver for development and the aspiration for World Heritage Listing.

- There is no current Plan for protection/interpretation of the sites Heritage.

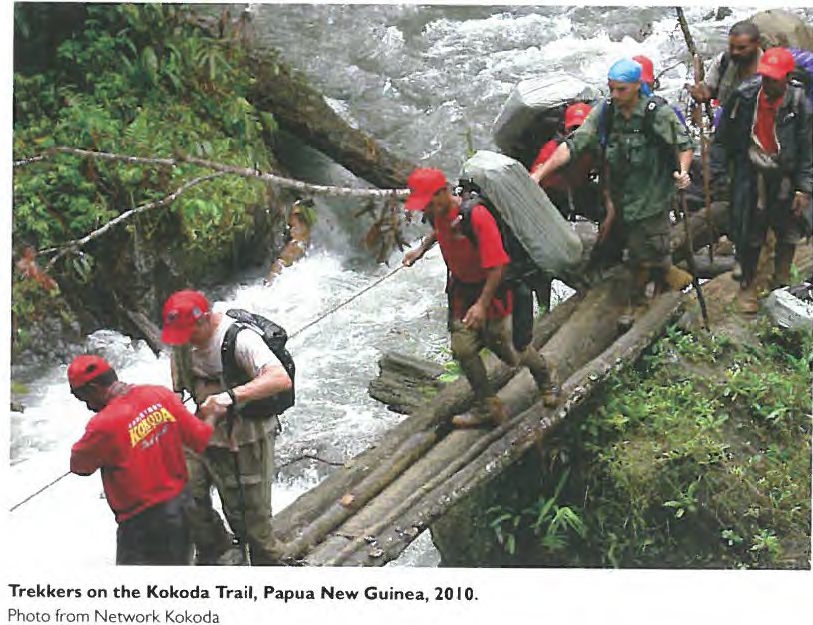

- A trekking industry has developed that clearly demonstrates the key relationship between the sites heritage, tourism and sustainable long-term development.

- There is little interpretation of ‘Kokoda Trail’ Heritage; Natural, Cultural or Military on the site itself.

- The majority of current interpretation is by private donors, is in poor condition and presents an adhoc, incoherent approach to the stories, events, actions and environment.

- An overall plan for interpretation on the Trail is warranted as one of the key means of safeguarding and protecting the sites heritage.

- An interpretive strategy focused on the trails history, its heritage and its special nature is the first step to enshrining the Kokoda Trail for future generations of both Australians and Papua New Guineans.

- Deploying permanent interpretation (consistent with an overall plan) will enhance the visitor experience whilst enshrining the environments core values and heritage.

- Deploying permanent interpretation (consistent with an overall plan) provides (demonstrably) opportunities of sustainable long-term development for the traditional landowners.

- Cost for development of a Heritage Interpretation Plan is in the order of $250,000.

- Cost for implementation of the Plan is in the order of $2 Million.

Kokoda Trail Funding Proposal by HPA Projects

Preface

Just a day’s travel from Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane and you can be on the Kokoda Trail.

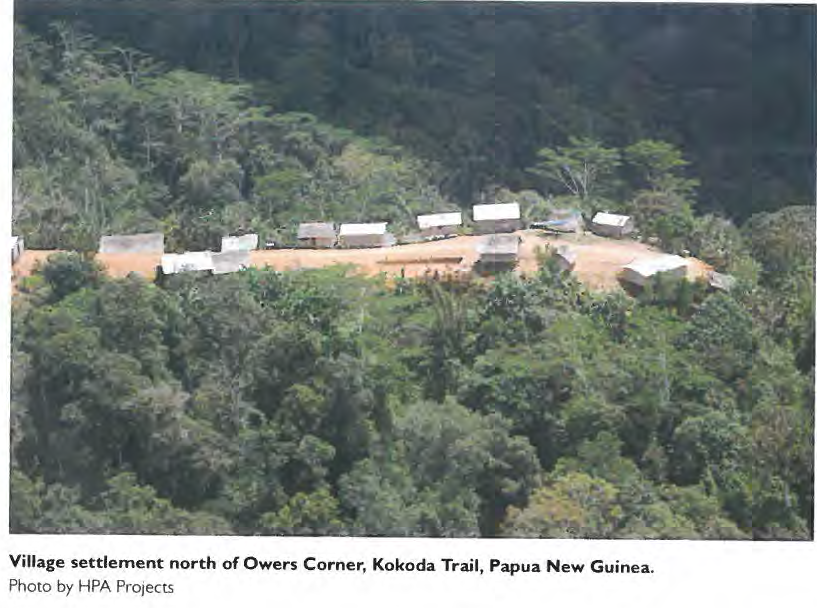

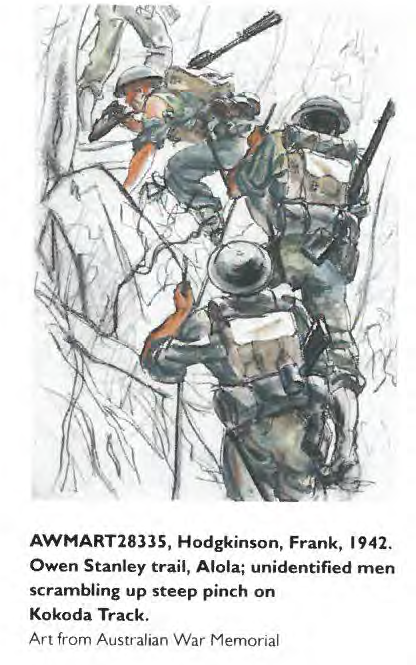

At the foot of the Owen Stanleys in Papua New Guinea you can look into the ancient landscape – majestic peaceful wilderness, nature in its full glory. There have been tracks across the mountains for thousands of years; the people who inhabit the region were gardening at the same time agriculture was developing in Ancient Egypt. The strength of natural and cultural heritage are beyond simple words; fascinating, awesome, daunting – world class.

Yet the battles of 1942 and the contemporary interest in ‘ Kokoda’ are what have made it Papua New Guinea’s No. 1 tourist attraction. In 1942 it was Australians and Papua New Guineans fighting Japanese for what was then Australian land. Young men in a bloody struggle for ‘their land’. The battle has become folklore in Australia – a place of pilgrimage like Gallipoli, Villers-Bretonneux, Sandakan, Passchendale.

Next year 2012 is the 70th Anniversary.

As a developing nation Papua New Guinea has numerous problems; governance, health, education and law the ‘major issues ‘. As the custodians it is not surprising that protection of heritage for PNG comes low down the priority list.

Few would argue that the Heritage of Kokoda shouldn’t be protected, but clearly it is beyond the means of Papua New Guinea. The question of who is the custodian is relevant. The Australian/PNG Governments ‘Joint Understanding Kokoda Initiative (2008)’ held promise of heritage protection however, implementation and funding would appear to have focused on health. safety and education. Four years on it seems that again heritage has been relegated.

There are two purposes to this report:

(i) The primary purpose is to establish the basis for heritage protection and interpretation on the Trail itself – A Kokoda Trail Heritage Interpretation plan; and

(ii) To seek funding for the development of the process from research through planning to implementation – An Implementation Process

On behalf of Network Kokoda, the sponsor of this report we seek your consideration of the report, the funding proposal and its findings.

Executive Summary

The Kokoda Trail is a world class heritage site. It is currently Papua New Guinea’s top tourist attraction and; it is a place of significance for Australians due to the military actions of 1942.

The heritage significance is derived from its cultural diversity, its natural biodiversity and untouched beauty and the Military heritage of WW2.

In October 2007 the Australian Government approved $15.8 million dollars in funding to assist Papua New Guinea “to protect the Kokoda Trail”. The Joint Understanding Kokoda Initiative (2008) has focused on health, safety and education on the trail itself – arguably with limited success .

In 20I0, the Independent ‘Howes Review of aid funding’ recommended that “future funding build on demonstrable success”; Kokoda is one of those successes, with a fledgling trekking industry that sustainably supports remote village communities. The growth of this trekking ‘industry’ is largely derived from the significance of Heritage that is Kokoda, to Australians.

Whilst the broad elements of a development strategy appear an inclusive part of the Kokoda Initiative, a documented and endorsed Heritage Plan would appear notably absent; notable as the trails village sustainability and its fledgling trekking industry are directly related to the Heritage. How this heritage is communicated and how it enhances the ‘significance of place’, whilst enshrining and protecting the core values inherent in the environment are key questions that are considered in this report.

The Kokoda Trails’ military heritage has an important place in Australia’s history that has been recognised by past governments. The ‘story of Kokoda’ has attracted significant interest over the past IO years evidenced primarily in trekker numbers on the Trail itself and significant literature

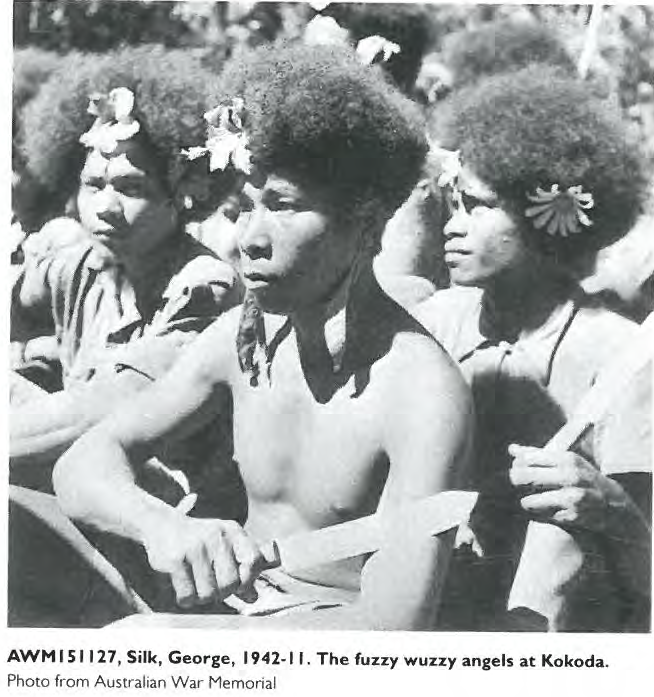

sales. However, in stark contrast the Papua New Guinea contribution to the Kokoda battles, affectionately remembered in Australia, as the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’ is largely absent from literature, and is slowly being consigned to memory alone. Unfortunately for PNG the heritage inherent in Kokoda has become ‘a local commercial benefit’ through trekking, rather than a shared national cultural heritage experience.

International examples show that Heritage and protection of heritage is generally underpinned by a formulated site specific Heritage Plan. Typically these documents constitute a foundation from which sustainable practices of development and tourism are derived. A heritage Interpretation Plan is considered the key mechanism for delivering Cultural and Natural Heritage for the sustainable benefit of the indigenous population, the environment and the visitor.

Currently, The Kokoda Trail has no Heritage Interpretation Plan, there is no Natural Heritage interpretation on the Trail; there is no Cultural Heritage interpretation on the Trail, generally military heritage interpretation has been installed by private ‘donors’, is poorly built, and in many cases shows significant factual inaccuracy. In effect, a deleterious environmental effect is in evidence.

This report seeks to establish the reasons, benefits and tangible outcomes that are derived from establishing a Heritage Plan for the Kokoda Trail and the costs associated with its implementation.

If funded the program of work can regard its primary objective as enshrining the sites Cultural, Natural and Military Heritage for the long-term sustainable benefit of the local people, and the nations of Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Introduction

The proposal outlines a body of work comprising research, consulting services and capital works. The core of the proposal, if funded, is a Master planning document for interpretation of Cultural, Natural and Military Heritage across the Kokoda Trail. The proposal also seeks funds for implementation of the Masterplan in a timeframe consistent with the 70th anniversary of the 1942 battles in 2012.

The proposal is focused on researching the Site’s Heritage, planning how this Heritage is maintained for the future, and implementing the plan within a known timeframe.

The document proposal does not examine infrastructure (roads, buildings, bridges) nor does it propose any works in relation to safety, healthcare, trekking operations or village economic sustainability.

The proposal document has been prepared based on research and site investigation.

Research has focused on the following areas: Military Heritage of The Trail for both Australians and the people of Papua New Guinea Tourism and Trekking operations over the past 10 years and their impact on the site.

Works undertaken in the last 4 years under the joint understanding between Australia and Papua New Guinea ‘Kokoda Initiative’ Program’.

In the past 10 years whilst public interest and trekking numbers have increased, there remains no overall strategy that focuses on the Site’s Heritage and how this heritage is protected, retained and interpreted.

This document should be read as a precursor to the research, development and implementation of a coherent Heritage strategy to this internationally significant site. If funded the program of work can regard its primary objective as enshrining the sites Cultural, Natural and Military Heritage for the benefit of the local people, and the nations of Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Background

In the last ten years approximately 40,000 trekkers have walked the Kokoda trail. The vast majority are young Australians. However, the increased numbers of Australian tourists and the greater importance that Australians have given to Kokoda appears to have had little broad impact in Papua New Guinea. From the recognition of the Trail as a tourism destination, the aim in recent years would appear to ‘develop a self-sustaining eco trekking industry for the benefit of local people (Koiari and Orokaiva). In 2004 a special purpose Authority was set up as a statutory body: The Kokoda Track Authority. It is similar to local level Government Authorities established elsewhere in Papua New Guinea to represent the interests of local people in dealings with mining companies.

Following a perceived threat to the Trail caused by mining exploration,

in October 2007 the Australian Government approved $15.8m funding to assist PNG to protect the Kokoda Trail. The majority of the funding ($14.9m) was appropriated to the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) as the lead agency in a Task Force to work with PNG agencies.

In 2008 the Australian Government established The Kokoda Initiative with goals of management, safety, tourism, health and sustainability being backed by considerable funding packages and in large part being administered in partnership with the Kokoda Track Authority. The Initiative states the goal in relation to tourism as ‘Building national and international tourism potential of the Owen Stanley Ranges and Kokoda Track Region, supported by a possible future World Heritage nomination.

Whilst a UN World Heritage nomination would appear a valuable long-term aspiration, the focus on development of international tourism provides a clear direction for both trekking operations and village sustainability. Further, the key tripartite relationship between village sustainability, Military Heritage and a growing trekking industry could be considered as a mutually reliant relationship.

Consistent with the stated objectives of the Kokoda Initiative, protection and development of the Trail through a mandated strategic Development Plan is warranted.

Whilst the broad elements of a developmentstrategy appear an inclusive part of the Kokoda Initiative, any form of Heritage Plan would appear notably absent; notable as the trails village sustainability and its fledgling trekking industry are directly related to the Heritage. How this heritage is communicated and how it enhances the trek experience, whilst enshrining and protecting the core values inherent in the people and the environment are key questions. Key questions that are possibly being considered under the Kokoda Initiative Program of Works.

The James Report 2009 ‘The Track – An Historical Desktop Study’ commissioned as part of the Kokoda Initiative (for Department of Environment, Heritage and Arts) is perhaps the first step to a Kokoda Heritage Interpretation Plan. It is a scholarly non-fictional anthology.

Whilst it can be regarded as a sound basis for further development, its objectives and terms of reference are unclear. Further the findings and recommendations of the Report are on the whole recommendations for further academic study that, whilst admirable appear inconsistent with the practical objectives of the Kokoda Initiative, in particular village sustainability and tourism growth.

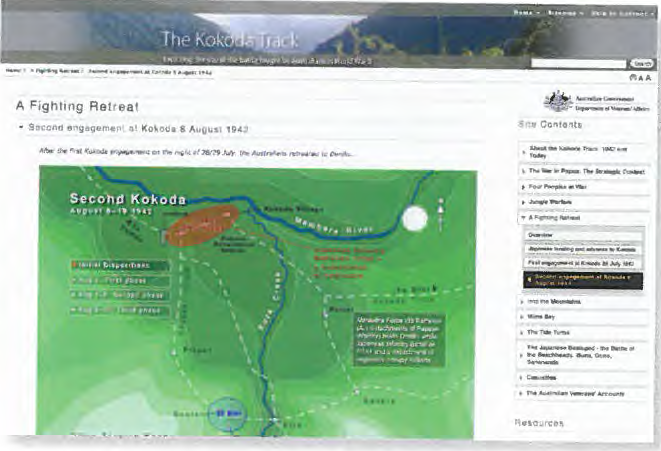

The department of Veterans Affairs website kokoda.commemoration.gov.au and the Kokoda Track Section is perhaps the best off site form of military heritage interpretation. It offers visitors complete and comprehensive Kokoda Track interpretation that covers battle sites as well as oral histories, interactive diagrams and some extremely good photographic records.

However, research into the sites performance and usage (alexa.com) show that the average time at the site is less than 2 minutes, the visit is usually by link and the number of pages viewed is 2 or less.

The purpose of a Heritage Plan is to focus on detailed assessment of how the history of environment, events, actions and people is interpreted (i.e. how it is told) and how this interpretation can directly enhance tourism potential whilst protecting the cultural and natural heritage values of the area. This is the basis of Heritage Site Development globally as defined under the United Nations ICOMOS Charter. The ICOMOS Charter for sustainable tourism in World Heritage Sites provides a simple set of development and interpretation principles . These principles are outlined in Section 13 of this report.

All of the ICOMOS principles are relevant however Principles 4 and 6 are key:

Principle 4 – Proactive Tourism Management

The contribution of tourism development and visitor activities associated with World Heritage Properties to their protection, conservation and presentation requires continuing and proactive planning and monitoring by Site Management, which must respect the capacity of the individual property to accept visitation without degrading or threatening heritage values. Site Management should have regard to relevant tourism supply chain and broader tourism destination issues, including congestion management and the quality of life for local people. Tourism planning

and management, including cooperative partnerships, should be an integral aspect of the site management system.

Principle 6 – Tourism Infrastructure and Visitor Facilities

Tourism infrastructure and visitor facilities associated with World Heritage Properties should be carefully planned, sited, designed, constructed and periodically upgraded as required to maximise the quality of visitor appreciation and experiences while ensuring there is no significant adverse impacts on heritage values and the surrounding environmental. social and cultural context.

The key points of background are therefore outlined as follows:

- The Kokoda Initiative (2008) has a stated tourism objective; a heritage plan appears absent from the strategy of development assistance.

- World Heritage listing under ICOMOS provides development principles that focus on the relationship of tourism, heritage and sustainability.

- The absence of coherent planning for protecting the Heritage of Kokoda will in time lead to dissolution and weakening of the core heritage values.

The key questions are therefore regarded as follows: Does the heritage of Kokoda warrant a long-term strategy? Who is the custodian of the heritage?

Can a heritage plan be developed and implemented? What benefits would be delivered?

This document and the following sections seeks to establish the reasons. purpose and framework for achieving a Kokoda Trail Heritage Site Interpretation Plan.

Kokoda

The Kokoda Campaign, The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels & The Papua New Guinea Perspective

The past decade has seen a remarkable increase in the number of Australians visiting the Kokoda Trail bringing economic opportunities for the Trail’s communities and transforming it into Papua New Guinea’s premier tourism location. This reflects a generation who recognise the Trail and the region’s historic significance, its exceptional beauty and natural landscape, and the unique experience it offers in connecting the people and culture of Papua New Guinea and Australia.

When Australians regained an interest in their Nation’s Military History in the early 1970’s and crowds returned to Anzac Day Ceremonies, interest focused almost solely on Gallipoli. Whilst the scholarly interest was largely pioneered by Ken Inglis the public interest was stimulated by the Australia Remembers Campaign and possibly more so by Peter Weirs epic film Gallipoli. Broad public interest was sustained through events such as the return of the Unknown Soldier in 1993 and state funeral for the ‘last of the Anzacs’ Alec Campbell in 2002. However long before the veterans of World War I would walk their final march, public interest firmly shifted to World War II. Both Prime Ministers Paul Keating in the early 90’s and later John Howard chose the Pacific commitments of 1942 and the Prisoner of War experiences of the region as ‘historic engagements with Asia’ and that ‘partnerships had been formed’. The Anzac legend, Howard noted ‘had found a new form’ they had demonstrated ‘mateship, courage and compassion… enduring qualities of our nation. The essence of a nations past and its hope for the future’.

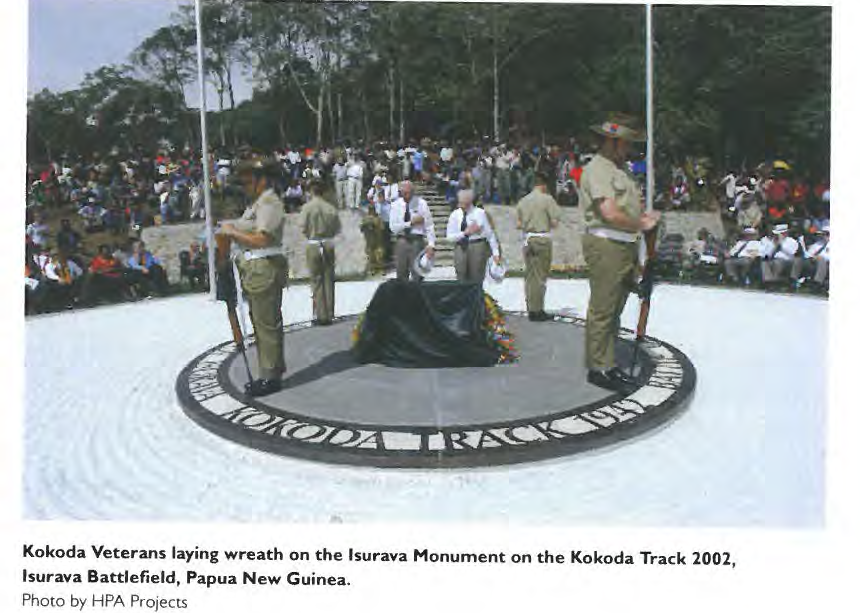

When Prime Minister Keating kissed the ground at Kokoda in 1992, he drew attention to the special nature of the place. It was the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda Campaign. Ten years later in 2002 Prime Minister Howard spoke at the dedication of the lsurava Monument on the Kokoda Trail – a 60th Anniversary ceremony, unveiling a mountain top Memorial on the lsurava Battlefield. Courage, Endurance, Mateship and Sacrifice, the four words inscribed on the Monument obelisks he proposed ‘symbolized the values of both the 1942 troops and the hope of the nations future’. (6)

In 2002 it did not seem outrageous that the media proclaimed Kokoda as the battle that turned the tide of war and why Kokoda carried greater significance for Australians than Gallipoli.

With the passing of the 60th Anniversary in 2002 one would have expected public interest to dwindle. On the contrary it increased, since 2002 the number of publications on Kokoda has been extraordinary.

The pages on Kokoda published since 2002 by Braga, Brune, Fitzsimmons, Ham, Hawthorne, James, McDonald and Rafferty total over 4000. The word ‘Kokoda’ itself is sufficient for a title.

Fitzsimmons’s book alone selling over 145,000 copies making it one of the most successful published ‘non fictional’ accounts of the modern era. Equally, trekking companies guiding visitors across the Trail have grown from 3 or 4 in 2000 to a registered 78 operators in 2010.

Trekking numbers almost doubled each year to 2009 until the tragic air crash near the lsurava Monument killed 13 people and put a temporary slowing on trekking numbers. Those numbers returned in 2011 and are projected to again return in 2012 with 70th anniversary focus making the Kokoda Trail one of (if not) Papua New Guineas ‘major tourist destination’s’.

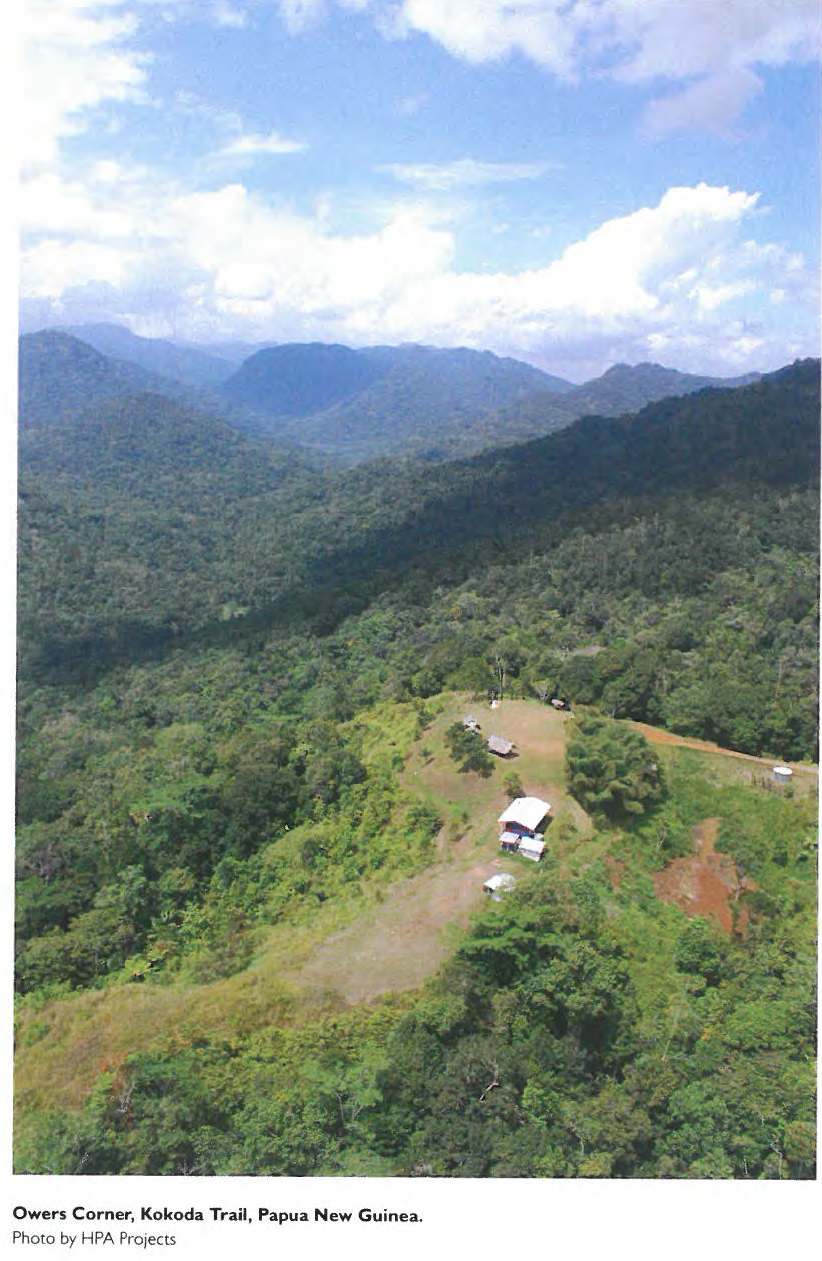

A tourism industry has developed albeit in its infancy that is directly intertwined with the Military events, actions and sacrifice of Australian and Papua New Guinea forces on the battlefields of 1942. From Kokoda in the north to Owers Corner in the south, a sinuous trail through an ancient landscape has captured the imagination of Australians and become a must read about, must know about or ‘must do’ experience.

In stark, almost total contrast for the people of Papua New Guinea the history and its significant consequences are little known, and unlike Australia, ‘Kokoda’ is certainly not in the national psyche of Papua New Guinea.

Despite the Papua New Guinea War commitment being over 50,000 men, this significant history has not devolved to a shared history that is able to galvanize a nation or contribute to a national sense of shared experience. Sixty years after the events there are few (if any) scholarly or popular accounts that cover the range of experiences of the Papua New Guinean people in the War and relate them to a broader context. 11>2 For a nation with a village based population of under 700,000 people, in 1939 the commitment of 50,000 men was enormous. Whole communities were dislocated if not decimated. The War transformed Papua New Guinea.

Where there had been 8000 foreigners in 1939, approximately 1.5 million (mostly military) had passed through by 1945 and over 200,000 had died there. Yet the experience to this day remains largely out of public sight or memory for most people of Papua New Guinea.

The difficulties faced by Papua New Guinea in trying to transform historic events into shared national experiences are illustrated in the many attempts to simply find a day as a means to commemorate the War. In the 5O’s and 60’s Anzac Day was a national holiday. However in 1975 it was deemed inappropriate to a newly independent nation as the references to the Turkish coastline and the Imperial Forces gave little relevance to

Papua New Guinea people.

Searching for a day that Papua New Guinea people would remember, the new Government chose August 15th, the day the war ended. It was an internationally significant day that held little for the people of Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea ex servicemen disliked it: a day that celebrated peace had little time for remembering battles, tributes to comrades and commemoration of the supreme sacrifice.

In 1982, the PNG Government again changed the date, this time to July 23rd.

On 23 July 1942 the Papuan Infantry Battalion ( PIB) had gone into battle forward of Kokoda near Awala. That made Remembrance Day more like Anzac Day: it was the first time that the PIB had gone into action, it was a precursor of a national institution entering the international arena, and it was a defeat. But the fighting on 23 July 1942 was a minor encounter before the withdrawal along the Kokoda Trail there were few casualties and perhaps none among the Papuan soldiers; the fighting was confused rather than heroic; and it was given slight significance at the time or in later histories. When the PIB opened fire with rifles and machine guns the Japanese replied immediately, and they were more numerous and had greater power, including mortars and machine guns. In that brief action, some Australian and Papuan soldiers withdrew before they were ordered and went further than expected; and just a few could be praised for doing more than they were asked, including the policeman, Lance-Corporal Sanopa, who guided the remaining troops out of Oivi on 26 July, Sergeant Katue, Military Medal, of the PIB who twice went alone to gather information on enemy positions and became the first Papuan soldier to be decorated, and Sergeant Dani, of the PIB, who from 23 July scouted the Japanese positions between Awala and Kokoda. Even those few names and events are little known in Papua New Guinea and there are few readily available places where citizens might find out about them .

Papua New Guinea leaders continued to make somewhat grand statements about the significance of July 23 and a National Holiday – with few of their people understanding why. Then in 2004 the Papua New Guinea Government declared that Anzac Day 25 April in future would again be a public holiday. At the same time July 23 is termed ‘Remembrance Day’; debate continues as to the form of ceremonies which have invariably become simply sporting events or for many just another working day.

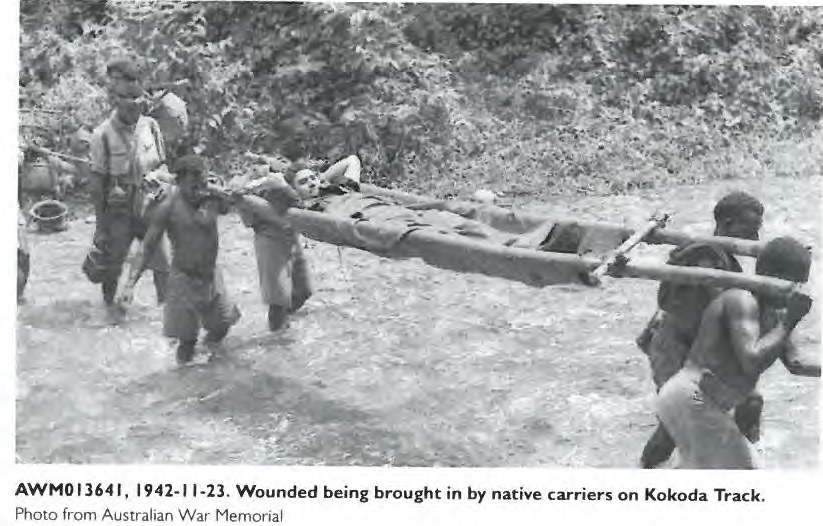

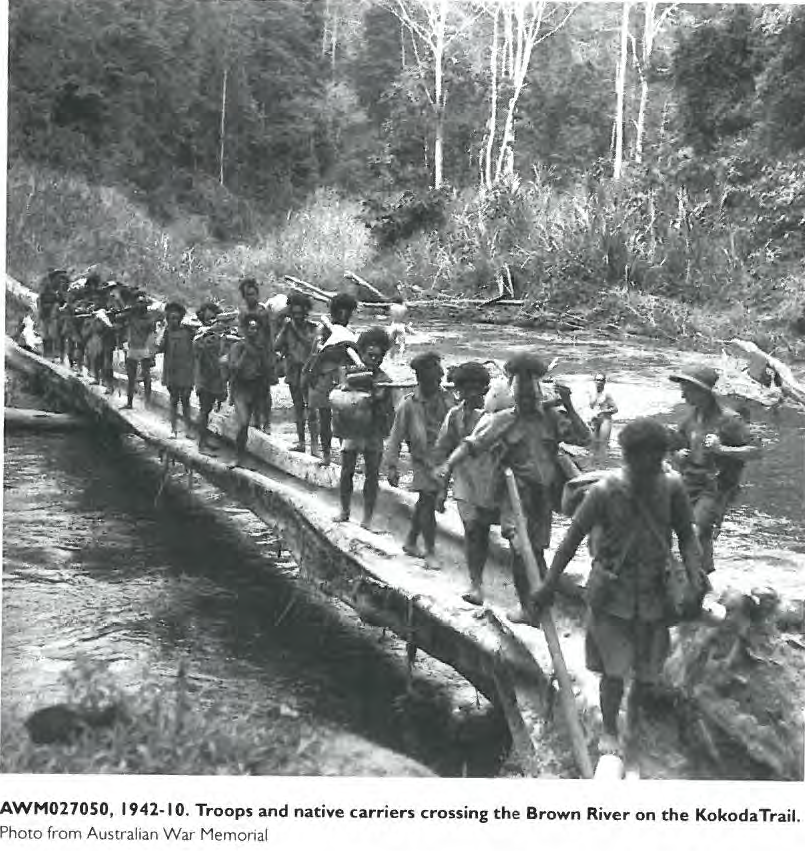

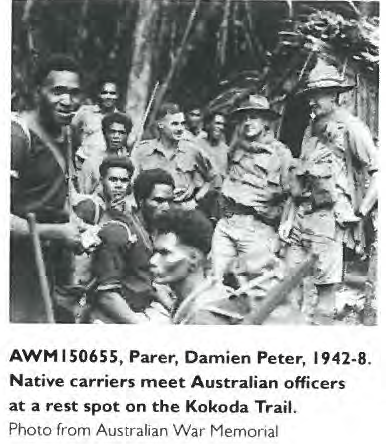

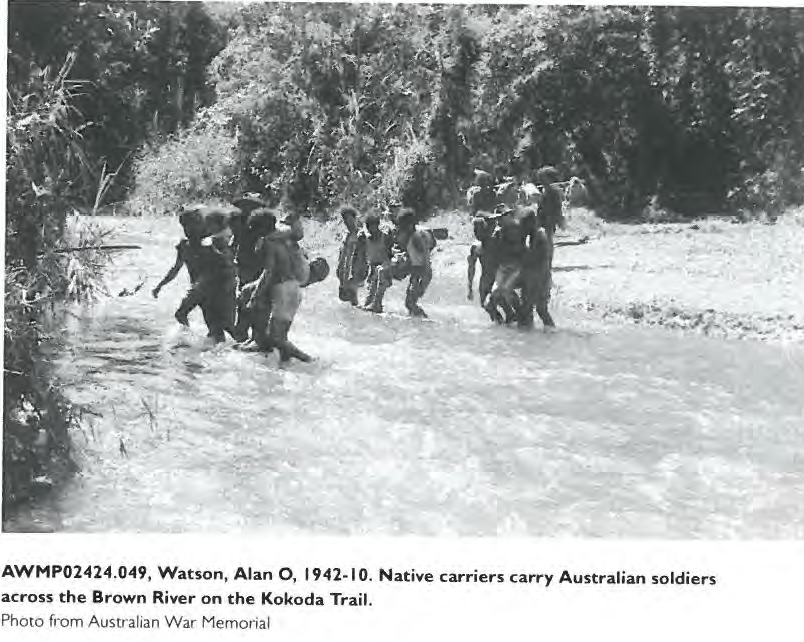

The number of Papua New Guineans serving during the war is almost impossible to determine. On the Kokoda Trail the approximate figures are known – these men and women became known as The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels. In their retreat from Kokoda to lmita Ridge from July 1942 the Australian forces numbered fewer than 3000. Popular media reports of 50,000 Papua New Guinea carriers are simply incorrect, as this figure is broadly derived from the rounded figure of the maximum number of carriers used by the Australian Army at any one time. It includes men working everywhere from Lae to Milne Bay in all categories of employment. A total number of 3000 on the trail itself can be substantiated however a figure closer to 1700 at the height of the campaign is considered more realistic.

The question of who the carriers were and where they came from is perhaps more important. This question and a definitive answer remains unknown. This is largely a result of a lack of scholarly research and/or an interest in a shared national history. The facts are not known therefore the history has eroded if not simply vanished. Whilst the term Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel is known in Australia it is largely forgotten in Papua New Guinea.

They carried stretchers through feet deep mud with the wounded down slimy defiles, through jagged ridges and valleys, terrible. rugged terrain, mountains and jungles and through fast flowing streams and rivers, and mosquito-infested swamps and grassplains. They were almost at the point of exhaustion, but they always kept two men awake at nights to take care of the patients, to wash their muddy limbs, to attend to their bandages and to give them their meals . The work of these natives has been outstanding. We owe them a lasting debt.

GENERAL BLAMEY, 1945

‘just about dark the boys gather in the huts in their village groups. They light a fire in the middle of the earth floor, curl up in their blankets and go off to sleep . The carrier’s day is done – several more tons of vital supplies are a day nearer the front – tomorrow they’ll be nearer still. When the war is over we should not forget how much of the white man’s burden was carried by the natives in the roadless jungle worfore.’

CHESTER WILMOT

The key points in conclusion:

- The Kokoda Trail and its heritage have an important place in Australia’s history that has been recognised by past governments.

- The ‘story of Kokoda’ has attracted significant interest over the past IO years evidenced primarily in trekker numbers on the Trail itself and literature sales.

- The Papua New Guinea contribution to the Kokoda battle affectionately remembered in Australia, as the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’ is largely absent from interpretation or commemorative elements on the Trail.

- The Trail history for Papua New Guinea is largely forgotten and has become ‘a local commercial benefit’ rather than a shared national cultural heritage experience .

Heritage Interpretation on the Trail

This section examines the current Status of Interpretation on the Kokoda Trail.

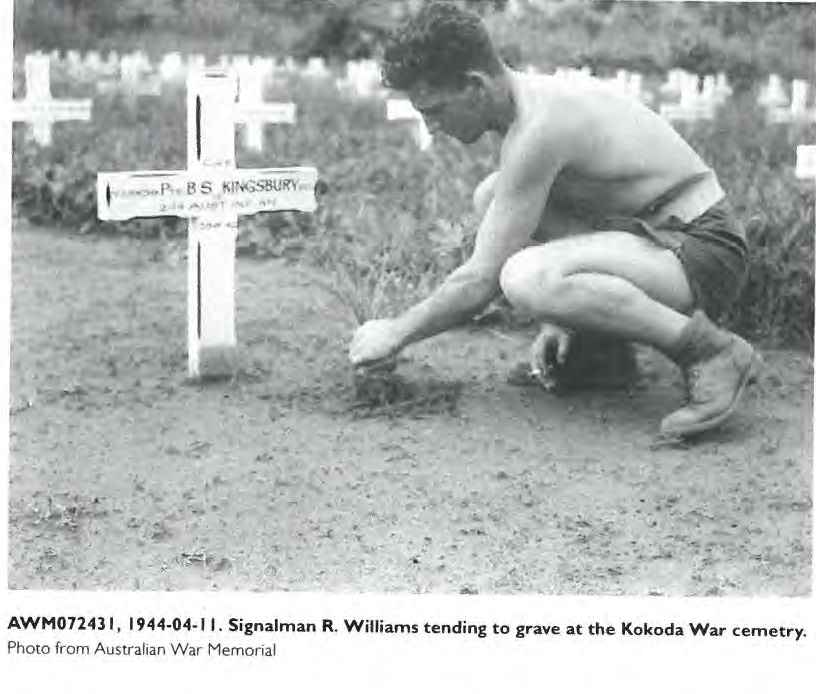

The following provides an overview of all forms of interpretation on the Trail itself. This includes structures that are called ‘Memorials’ or other elements of built structure that provide interpretation to the visitor or trekker. Marking the site began before World War II ended.

In early 1945 General Thomas Blameey initiated a scheme for a series of historical monuments to be erected throughout Papua New Guinea to commemorate the Australian Military Force’s achievements during the war. When the first large pilgrimage of veterans returned to Kokoda in November 1967, to mark the 25th Anniversary of the re-taking of the village, the commemorative program was centred on the Kokoda Memorial and parade ground.

‘on the 30th the Australians began their fiercely fought withdrawal from lsurava to loribaiwa. This was the culminating point of the campaign. The advantage passed from the Japanese to the Australians’.

JAMES MORRISON

Alongside the Kokoda memorial is the Memorial of the native carriers of the Kokoda Trail, also called the ‘Papuan carriers’ memorial. This memorial, initiated and funded by Bert Kienzle, was dedicated on 2 November 1959. A third memorial was built by the Japan- Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society in February 1980, it was dedicated to all of the campaign’s war dead (Japanese, Australian, and Papuan). There are also other commemorative plaques in the station’s grounds.

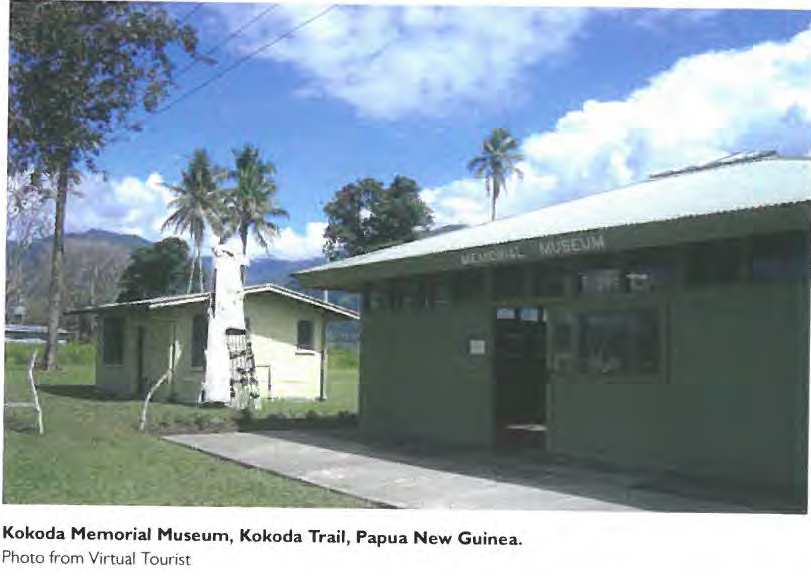

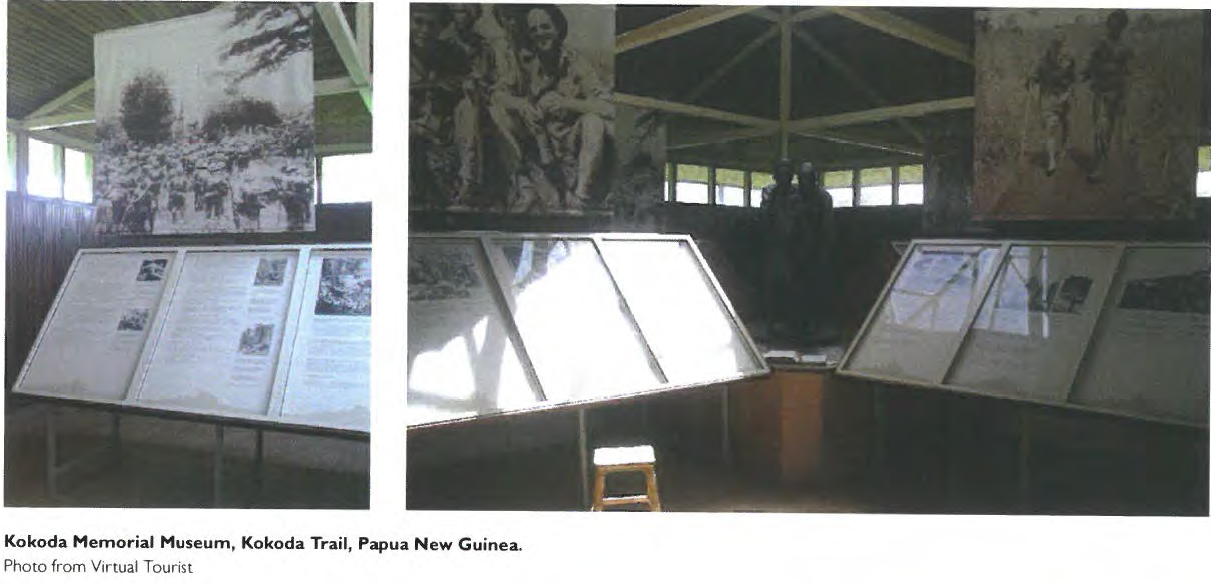

In 1995 Prime Ministers Paul Keating and Julius Chan opened a memorial museum in Kokoda, named after Bert Kienzle.

The Kokoda ‘Memorial Museum’ is a small shed containing information panels. The ‘Museum’ features static interpretation and photographs.

It is ageing and rarely open.

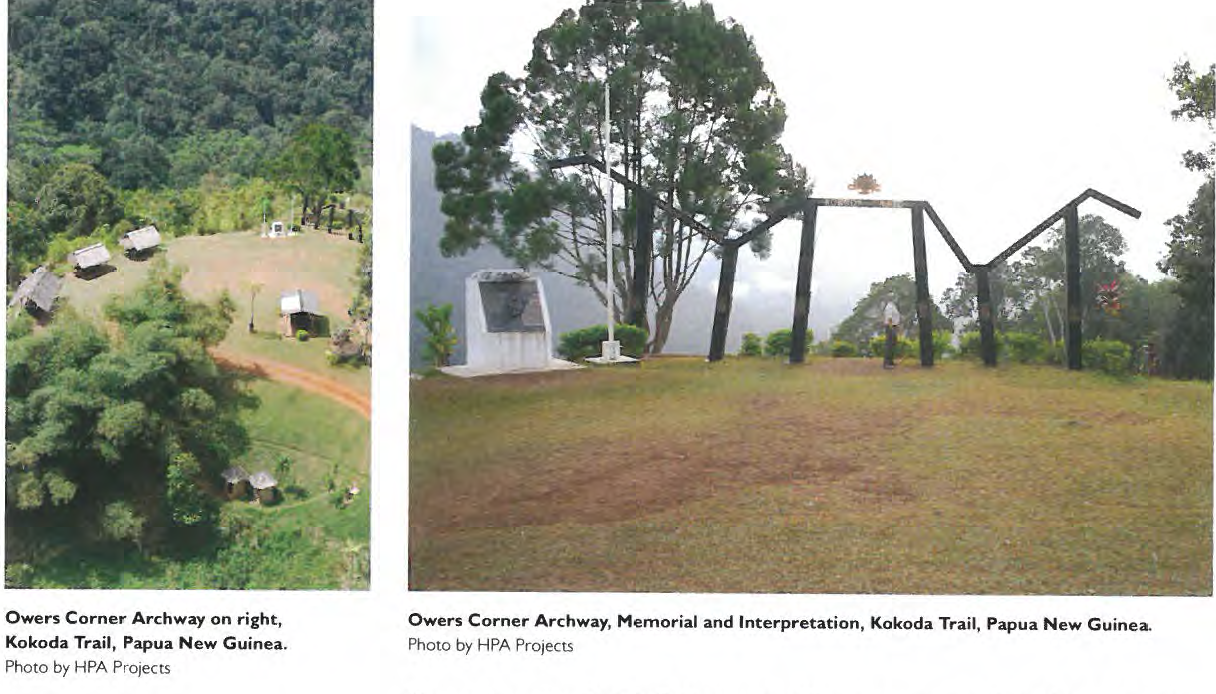

Dubbed ‘McArches‘, the ‘Kokoda Track Archway’ was erected in 2011 by private donors, much to the surprise of the Kokoda Track Authority and local people.

This situation is fairly typical to military heritage sites where there is little control. management or oversight. Unfortunately whilst the intent is well meaning the outcome in time will evidence a deleterious effect on the environment.

Brigade Hill is the site of one of the major battles of the Kokoda Campaign. The site itself offers majestic 360 degree overlook views across the Owen Stanley Ranges. Significantly it is one of the few locations where trekkers are able to visualise the scale of the fighting. The site features a bronze plaque installed by private donors.

‘Brigade Hill is a natural citadel. apparently inviolable, at the summit of Mission Ridge, just south of Efogi. The summit and jungle clad flanks command a strong defensive position. Potts’ troops were strung out ahead, between the summit and the ridge’s north facing foothlils, overlooking old Efogi, a distance of about one mile or so along the track. The fresh 2/27th

Battalion was at the vanguard on the hills near the approaches to the enemy held village.’

PAUL HAM

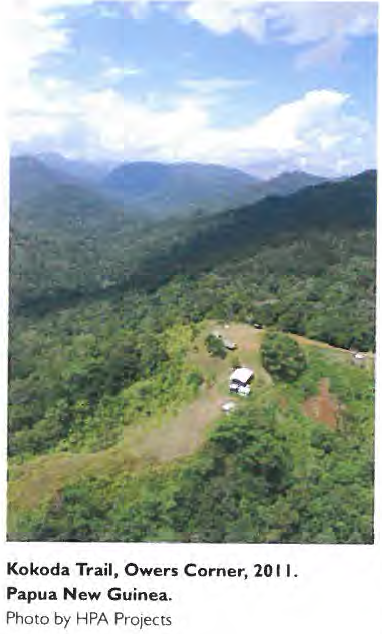

Owers Corner, as one of the gateways to the Trail (the other being Kokoda) offers visitors a spectacular overlook. It is regularly visited by non trekking visitors from Moresby who day hike to the Goldie River. For trekkers who start from (or finish) at Owers Corner it is a special place of quiet reflection.

There is little in the way of explanation as to the sites cultural, natural or military heritage.

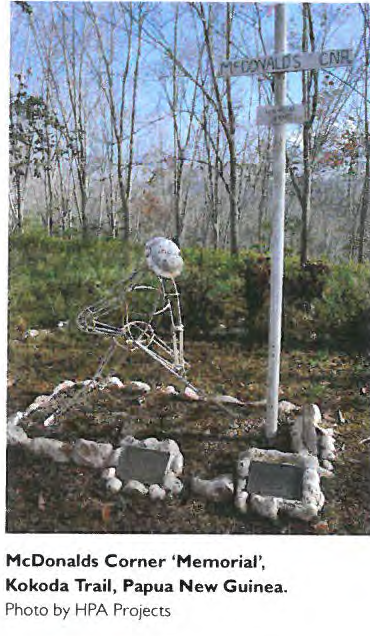

Generally, across the Trail the nature of interpretation is that of singular small elements installed on an ad hoc basis over time. The sponsors/installers are on the whole well-meaning enthusiasts. (It should be noted that without considerable efforts of these individuals that the Trail would have little commemorative features or interpretation.) The lsurava Memorial and Kokoda Museum as government sponsored sites are the exception.

lsurava features both commemorative elements and bilingual interpretation. However, it should be noted that lsurava is only accessible by trekkers and is battle site specific. The ‘Museum’ at Kokoda is an information building and whilst functional the interpretation is showing signs of deterioration consistent with its age.

An overall review of current interpretation on the Trail can be summarized as follows:

- There is no Natural Heritage interpretation on the Trail; there is no Cultural Heritage interpretation on the Trail;

- There are a number of small plaques installed over the years that act as commemorative markers of the Military Heritage;

- The lsurava Memorial is the only major Memorial element on the Trail itself, the Kokoda Parade Ground Memorials are modest ‘markers’ with little interpretation;

- Generally interpretation is ad hoc, provides little context and in many cases shows significant inaccuracy and/or inconsistency;

- The Kokoda ‘Memorial Museum’ is over 15 years old and in relatively poor condition;

- With the exception of lsurava and Kokoda Parade Ground/Museum Military Heritage Interpretation across the Trail is either in poor condition, is inconsistent, inaccurate or non existent.

Proposed Detail

This section provides a draft outline of the scope of work that is proposed. The project is separated into 3 stages and detail is provided as to the tasks involved, roles and outcomes for each stage. It should be noted that the scope outline is at this stage draft. A complete project definition outline is regarded as necessary at project inception.

Stage 1 – Research and Consultation

Stage 1 consists primarily of research with preliminary consultation of stake holders .

Draft Task Outline

Project definition can be documented to outline terms of reference, stakeholders, limitations of scope and timeframe.

Establishment of Project Stage Deliverables .

Establish Panel of Expert Historians – 3 or 4 recommended.

This is a key activity and will require the group to make time available. The role of the historian panel is to provide overview consensus in terms of historical significance, hierarchy and story. A panel of historians has not been selected however the following are regarded as appropriately qualified with specific relevant knowledge in the field – Dr Karl James (Aust ralian War Memorial), Prof David Horner. Peter Ryan, Bob Breen, Richard Reid (OYA).

Please note that these individuals have not been consulted in respect of this project, as this would be premature in the context of this funding proposal.

It should also be noted that the panel identified above are recognised Military Heritage historians, if the scope was to expand to Interpretation of Cultural and Natural Heritage the panel make up would change to include expertise in these fields.

Field Review and Documentation of existing conditions at key locations across the site. This will require the project team to trek the trail.

Conduct stakeholder consultation reviews of project activities and anticipated outcomes.

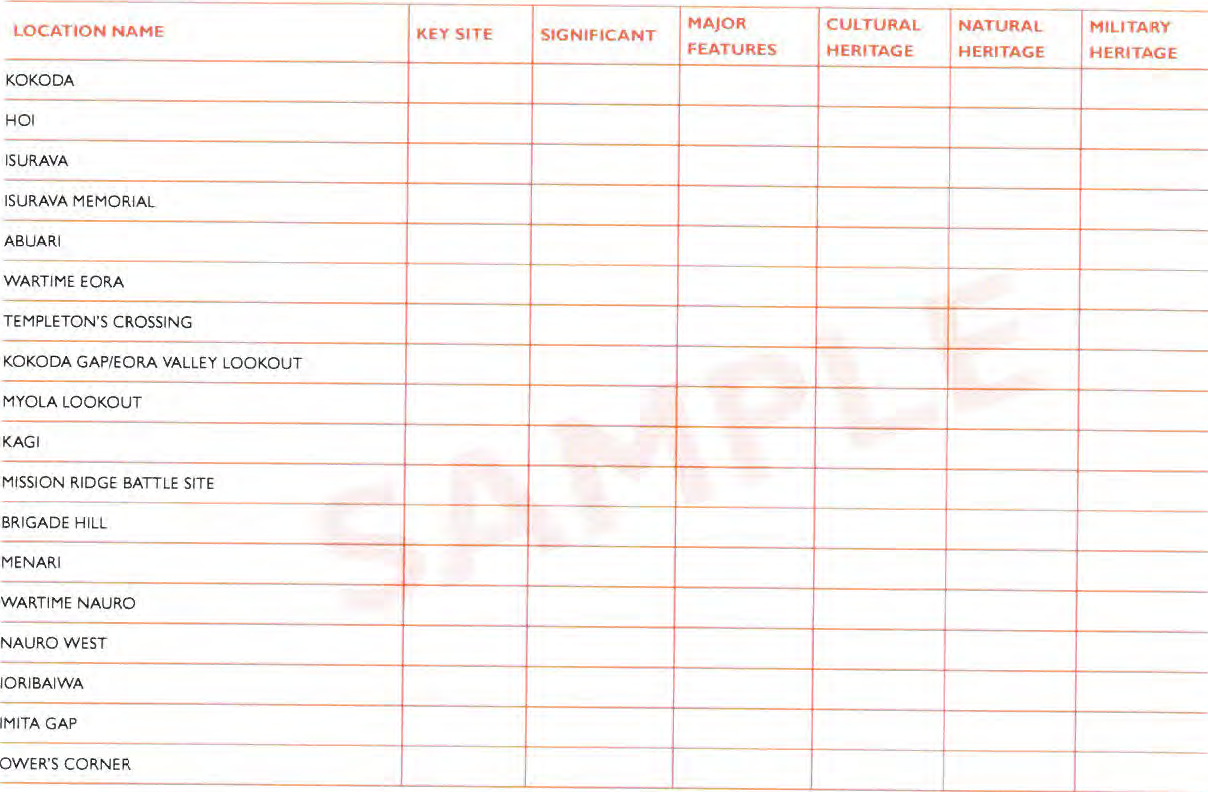

Formulation of Site Matrix.

The purpose of a Site Matrix is to consolidate a large site into a singular entity that can then be examined on the basis of a set of criteria. The following is a sample only, the criteria a draft based on the like projects.

Criteria for Site Assessment would need to be formulated around a variety of factors.

The following is simply an example:

- Key Site (Military, Cultural, Natural Heritage)

Site that is accessible and able to support detailed Interpretation that will enhance both understanding and support local sustainability;

- Significant Site (Military, Cultural, Natural Heritage)

Site that provides evidence or can be interpreted for greater understanding using specific evidence;

- Marker Site

Site that provides context to a greater set of evidential features or actions that may not be present or obvious to the casual observer .

Key Sites of Military Heritage are currently considered as follows: Kokoda, lsurava Memorial, Brigade Hill , Eora Creek and Ower’s Corner.

- Significant Sites of Military Heritage are currently considered as follows: Kovello, Abuari, Templeton’s Crossing, Kokoda Gap/Eora Valley Lookout, Myola lookout, Mission Ridge Battle Sites, Menari, Ofi Creek Camp, loribaiwa, McDonald’s Corner, lmita Gap.

Site Identification Matrix (Draft for illustration purposes only).

Stage 2 – A Documented Plan

Stage 2 is the process of drawing together the research outcomes, reviewing the consultation, designing a set of solutions and formalizing an implementation plan. This could be termed a ‘Masterplan’ however it is felt that this is too broad in terminology. A more appropriate name may be ‘Heritage Interpretation Plan and Implementation Strategy’.

Draft Task Outline

Review of stakeholder response and Site Matrix/Matrix Criteria.

Research and review of trekking operations, camp-sites, pacing and visitor numbers. This is essentially to gain an understanding of the current ‘audience’ and how interpretation can best inform a future audience .

Review of cultural and natural heritage interpretation imperatives and formulate a site wide methodology of incorporating Military Heritage Interpretation.

Formulate an Interpretation hierarchy ranging information markers to ‘major’ elements based on the site Matrix information.

Formulate and document a definition of prohibited elements and/o r a system of controlling future proposed elements, i.e. akin to a set of development control plans (DCP).

Identify any existing elements for removal.

Facilitate a stake holde r process whereby understanding and consensus is achieved around the above proposal.

Develop detailed costing.

Identify/Design a palette of materials that is consistent with the DCP objectives that are considered appropriate, highly durable and fit for purpose.

Develop the proposed implementation strategy.

Establish a document around Stage I and 2 that is endorsed at Papua New Guinea Government level, endorsed by stakeholders and finalized for Implementation Review by Australian Government.

Stage 3 – Implementation

Stage 3 is the implementation of the Plan.

At this stage Implementation may be considered a phased process however a relatively small project of this nature is likely to achieve significant economies of scale when implementation is undertaken as a singular process. This is largely due to the large site. issues of accessibility and therefore cost.

The draft timeline at Section 9 out lines an implementation duration of 20 weeks with target dates set to coincide with 70th Anniversary ceremonies. This is regarded by the author as an achievable timeframe however set time frames to coincide with hard (often media driven) deadlines require acknowledgment throughout the process, i.e. from the outset. We note that the lsurava Memorial Program was 14 weeks from concept to completion and involve d a supply chain from central Australia (stonework) to site in Papua New Guinea.

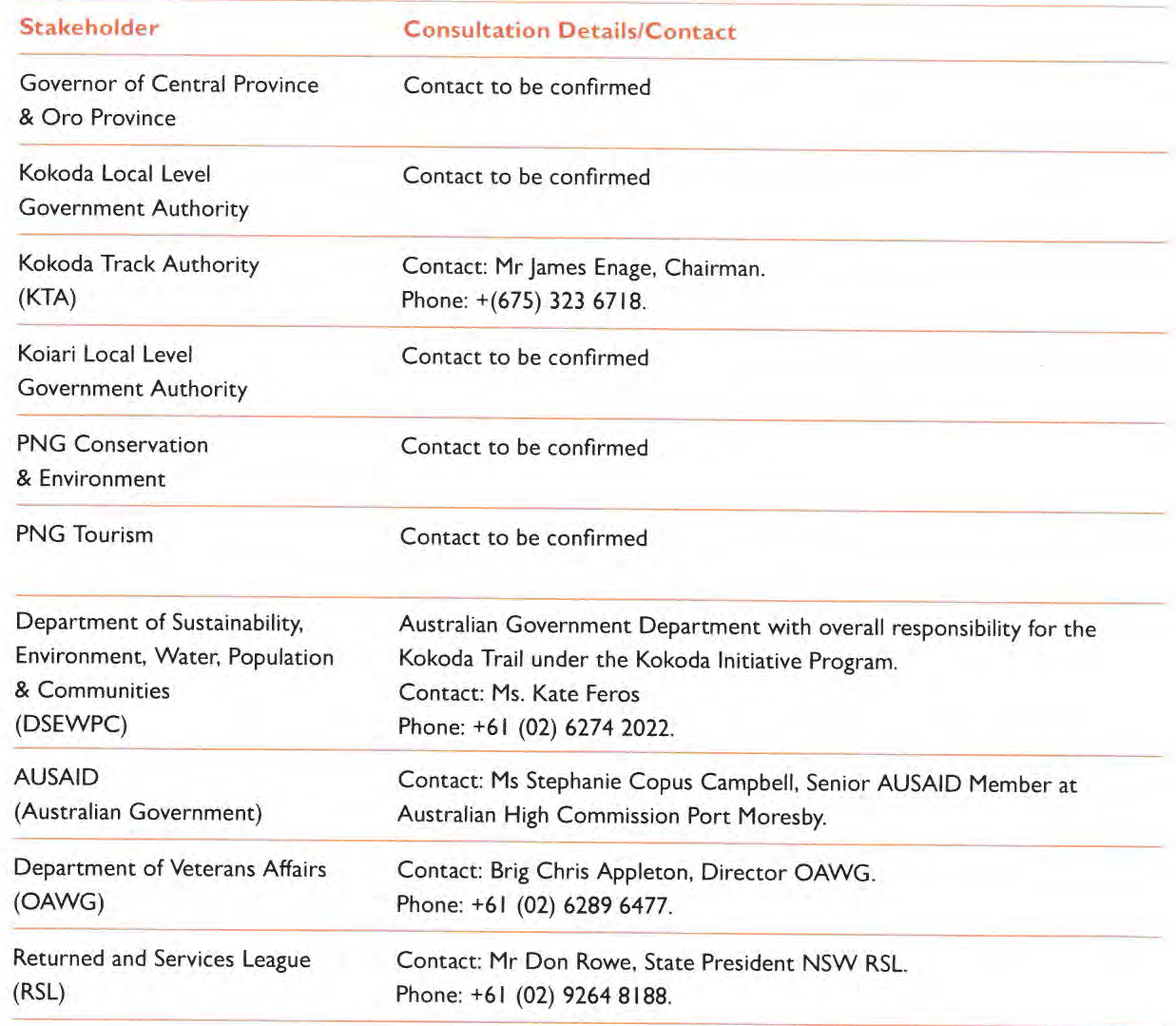

Stakeholders and Consultation

Should the funding proposal be considered, the following stakeholder groups are regarded by the author as key participants in a consultative process.

Cost

Cost has been assessed on the basis of the following :

(i) Previous experience with similar historic site projects and the processes associated with development of site interpretation.

(ii) Experience of working and implementing capital works on the Trail itself.

(iii) Implementation costs are allowances based on assumptions regarding scope.

Costs are provided as indications in terms of order of cost. They are not quotations or lump sum offers .

Stage 1- Cost Research and Consultation

Stage 1 out lines a process of project definition, research including

research input by eminent historians, field review, stakeholder consultation, site assessment and site detail documentation

(Refer Section 6 pages 21, 22 for detail.)

Order of Cost: $185,000

Stage 2 Cost – Plan

Stage 2 draws together the research phase outcomes to produce documentation that can be endorsed, and implemented (Refer section 6 pages 22, 23).

Order of Cost: $245,000

Stage 3 Cost – Implementation

The scope assumptions are that allocations will be in two tiers, Major Site and Other. lsurava Memorial is considered a Major Site, Kokoda Village and Owers Corner as the two ‘gateways’ to the Trail are considered Major Sites. Owers Corner could be considered of greater importance given its accessibility from Port Moresby. Brigade Hill is considered the other Major Site given its military heritage significance, its location and its beauty.

Order of Cost: $1.5 million

TOTAL INDICATIVE ORDER OF COST $1.8-$2 MILLION

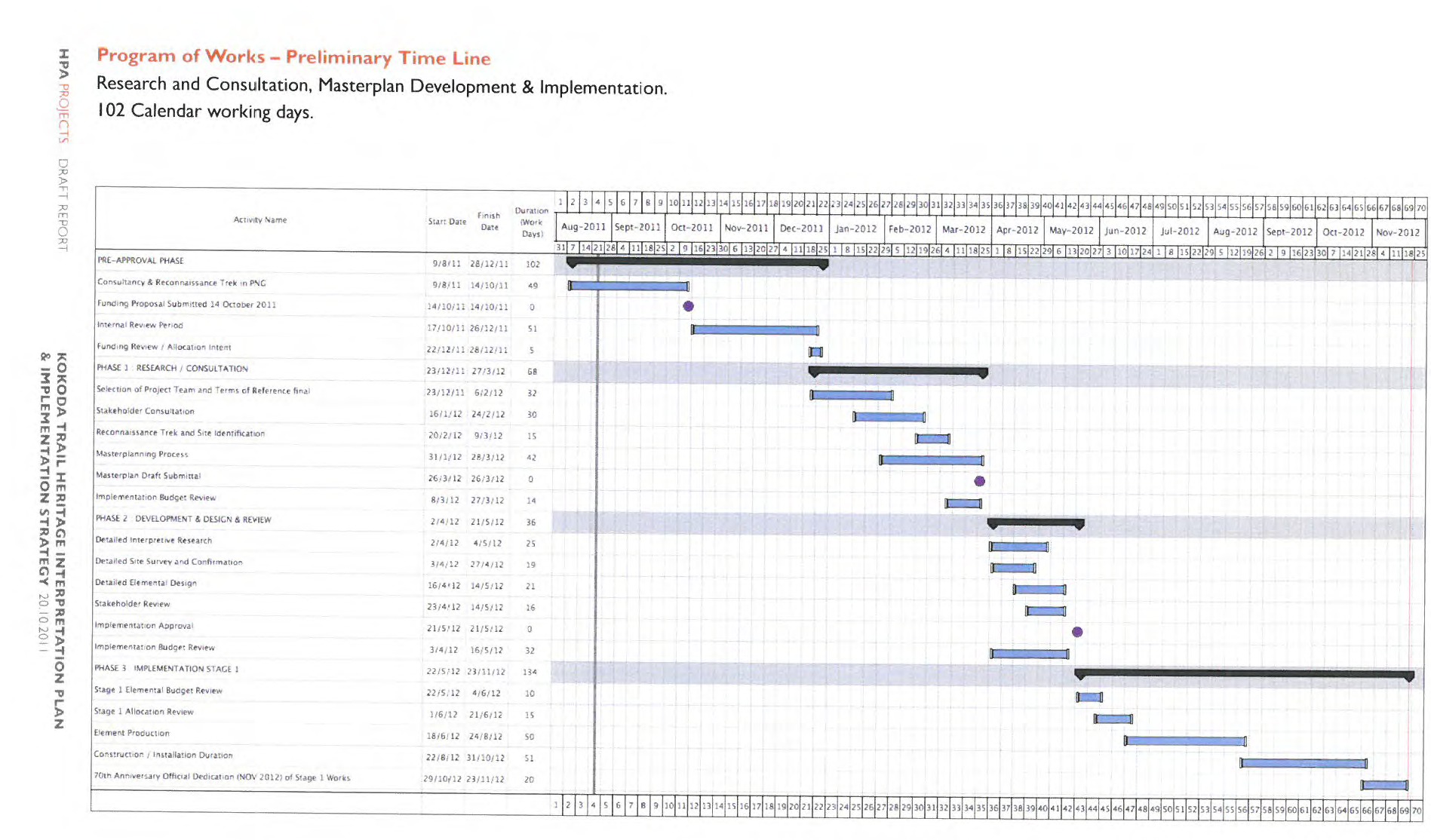

Time

For the purpose of this proposal a preliminary timeline has been established. The focus is substantial completion of all elements to coincide with 70th Anniversary activities and events in late 2012.

The key stages and dates are summarized as follows : Funding Proposal Report Submitted – October 2011 Project Commencement – December 20th.

Stage I Research and Consultation – Completion March 2012

Stage 2 Masterplan Development – Completion May 2012

Stage 3 Implementation – Commencement May 2012 Completion November 2012

Time

For the purpose of this proposal a preliminary timeline has been established. The focus is substantial completion of all elements to coincide with 70th Anniversary activities and events in late 2012. The key stages and dates are summarized as follows:

- Funding Proposal Report Submittal – October 2011

- Project Commencement – December 2011

- Stage 1 Research and Consultation – Completion March 2012

- Stage 2 Masterplan Development – Completion May 2012

- Stage 3 Implementation – Commencement May 2012

- Completion November 2012

Conclusions

The Kokoda Trail is an important heritage site for both Australia and Papua New Guinea.

The heritage values of the Kokoda Trail are unique and in evidence.

As custodian, Papua New Guinea is not able to protect or manage the heritage.

The Kokoda Initiative cites tourism as a key driver for development and the aspiration for World Heritage Listing.

There is no current Plan for protection/interpretation of the sites Heritage.

A trekking industry has developed that clearly demonstrates the key relationship between the sites heritage, tourism and sustainable long-term development.

There is little interpretation of ‘Kokoda Trail’ Heritage; Natural. Cultural or Military on the site itself.

The majority of current interpretation is by private donors, is in poor condition and presents an adhoc, incoherent approach to the stories, events, actions and environment.

An overall plan for interpretation on the Trail is warranted as one of the key means of safeguarding and protecting the sites heritage.

An interpretive strategy focused on the trails history, its heritage and its special nature is the first step to enshrining the Kokoda Trail for future generations of both Australians and Papua New Guineans.

Deploying permanent interpretation (consistent with an overall plan) will enhance the visitor experience whilst enshrining the environments core values and heritage.

Deploying permanent interpretation (consistent with an overall plan) provides (demonstrably) opportunities of sustainable long-term development for the traditional landowners.

Cost for development of a Heritage Interpretation Plan is in the order of $250,000.

Cost for implementation of the Plan is in the order of $2 Million.

The 70th Anniversary of the Kokoda battles provides a sound focus for implementation that is achievable should funding be made available, consistent with the time frames noted .

Principles for Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage Sites

Preamble

The Principles for Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage Properties define cooperative stakeholder relationships among all relevant government agencies, public and private tourism sectors, civil society including NGO’s. visitors. site management. museums and community members, such that tourism and visitation associated with World Heritage Properties contributes to the long-term sustainability of their heritage values and sense of place. while generating cultural and socio-economic benefits to the local population and surrounding region. These cooperative relationships are built on a shared concern for the long-term protection and conservation

of natural and cultural heritage places and their visitor attract ion.

World Heritage Properties represent ecological. geological. material. intellectual and spiritual resources that are the common heritage of humanity. They provide an important narrative of environmental and historical development and serve as foundations for contemporary social identity and development. Properties inscribed in the World Heritage List are recognised for their Outstanding Universal Values. Many listed properties may have a range of additional or complementary heritage values that are established by further research or ascribed by the community .

World Heritage Properties are also among the most popular and heavily promoted visitor and tourist attractions in many countries. The dramatic current and projected growth of international and domestic travel represents both challenges and opportunities for World Heritage sites and surrounding populations. Poorly managed tourism or excessive visitor numbers at a site can pose major threats to the heritage significance of the place and degrade the quality of the visitor experience. Tourism development and visitor activity should enhance the visitor’s understanding and appreciation of the heritage values through interpretation. presentation and visitor services. Sustainable tourism relies on the development and delivery of quality visitor experiences that do not degrade or damage any of the Property’s natural

or cultural values and visitor attraction.

Much tourism promotion, visitor activity, cultural exchange and economic development associated with World Heritage Properties cakes place in the surrounding locality. the nearby tourism destination, elsewhere in the country or internationally. Sustainable and responsible tourism development and visitor management requires effective, cooperative commitment and coordination between site management and all relevant public agencies and private enterprises.

The World Heritage Convention requires States Parties to protect the Outstanding Universal Value of the inscribed properties under their responsibility. Article 4 of the Convention identifies “Presentation” of the Outstanding Universal Value as being of equal importance to its “Identification, Protection, Conservation and Transmission”, to future generations. Responsible tourism management and the generation of widespread public support for protection and conservation should be a major contributor to the aims and objectives of the World Heritage Convention

These Principles recognise and build upon the Charters and Guidelines already developed by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UN World Tourism Organisation, ICOMOS, IUCN, ICOM and other international stakeholders to ensure best practice tourism at heritage places .

Principle I – Contribute to World Heritage Objectives Tourism development and visitor activities associated with World Properties must contribute to and must not damage the protection, conservation, presentation and transmission of their heritage values. Tourism should also generate sustainable socio-economic development and equitably contribute tangible as well as intangible benefits to local and regional communities in ways that are consistent with the conservation of the properties .

Principle 2 – Cooperative Partnerships

World Heritage Properties should be places where all stakeholders cooperated through effective partnerships to maximise conservation and presentation outcomes, whilst minimising threats and adverse impacts from tour ism .

Principle 3 – Public Awareness and Support

The Promotion, Presentation and Interpretation of World Heritage Properties should be effective, honest, comprehensive and engaging. It should mobilise local and international awareness, understanding and support for their protection, conservation and sustainable use.

Principle 4 – Proactive Tourism Management

The contribution of tourism development and visitor activities associated with World Heritage Properties to their protection, conservation and presentation requires continuing and proactive planning and monitoring by Site Management, which must respect the capacity of the individual property to accept visitation without degrading or threatening heritage values. Site Management should have regard to relevant tourism supply chain and broader tourism destination issues, including congestion management and the quality of life for local people. Tourism planning and management, including cooperative partnerships. should be an integral aspect of the site management system .

Principle 5 – Stakeholder Empowerment

Planning for tourism development and visitor activity associated with World Heritage Properties should be undertaken in an inclusive and participatory manner, respecting and empowering the local community including property owners, traditional or indigenous custodians, while taking account of their capacity and willingness to participate in visitor activity.

Principle 6 – Tourism Infrastructure and Visitor Facilities

Tourism infrastructure and visitor facilities associated with World Heritage Properties should be carefully planned, sited, designed, constructed and periodically upgraded as required to maximise the quality of visitor appreciation and experiences while ensuring there is no significant adverse impacts on heritage values and the surrounding environmental, social

and cultural context .

Principle 7 – Site Management Capacity

Management systems for World Heritage Properties should have sufficient skills. capacities and resources available when planning tourism infrastructure and managing visitor activity to ensure the protection and presentation of their identified heritage values and respect for local communities .

Principle 8 – Application of Tourism Generated Revenue

Relevant public agencies and Site Management should apply a sufficient proportion of the revenue derived fro m tourism and visitor activity associated with World Heritage Properties to ensure the protection, conservation and management of their heritage values .

Principle 9 – Contribution to Local Community Development

Tourism infrastructure development and visitor activity associated with World Heritage Properties should contribute to local community empowerment and socio-economic development in an effective and equitable manner.

Glossary

This glossary has been prepared to provide those who use and implement the ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter with a consistent terminology.

Access to significant features, values and characteristics, includes all form of access, including physical access, where the visitor experiences the place in person, intellectual access, where the visitor or others learn about the place, without possibly ever actually visiting it and emotive access where the sense of being there is felt, again even if a visit is never undertaken .

Authenticity describes the relative integrity of a place, an object or an activity in relation to its original creation. In the context of living cultural practices, the context of authenticity responds to the evolution of the traditional practice. In the context of an Historic Place or object. authenticity can encompass the accuracy or extent of its reconstruction to a known earlier state.

Biodiversity describes the variety of life forms. the different plants. animals and micro-organisms. the genes they contain and the ecosystems they form.

Conservation describes all of the processes of looking after a Heritage Place, Cultural Landscape. Heritage Collection or aspect of Intangible Heritage so as to retain its cultural, indigenous or natural heritage significance. In some English speaking countries, the term Preservation is used as an alternative to Conservation for this general activity.

Conservation Community includes all those who work towards the protection. conservation. management and presentation of the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

Culture can be defined as the whole complex of distinctive spiritual. material. intellectual and emotional features that characterise a community, society or social group. It includes not only arts and literature, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems. traditions and beliefs. Cultural encompasses the living or contemporary characteristics and values of a community as well as those that have survived from the past.

Cultural Exchange describes the process or processes whereby a person or group of people experience the respective Culture. lifestyle and Heritage of another person or group.

Cultural Heritage is an expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation, including customs, practices, places, objects. artistic expression and values. Cultural Heritage is often expressed as either Intangible or Tangible Cultural Heritage .

Cultural Heritage Significance means the aesthetic, historic. research, social. spiritual or other special characteristics and values a place, an object or a custom may have for present and future generations.

Cultural Landscapes describe those places and landscapes that have been shaped or influenced by human occupation. They include agricultural systems, modified landscapes, patterns of settlement and human activity, and the infrastructure of product ion, transportation and communication. The concepts of cultural landscapes can be useful in understanding the patterns of activity as diverse as industrial systems, defensive sites and the nature of towns or villages .

Cultural Resources encompass all of the Tangible and Intangible Heritage and living Cultural elements of a community.

Cultural Tourism is essentially that form of tourism that focuses on the culture, and cultural environments including landscapes of the destination. the values and lifestyles, heritage, visual and performing arts, industries, traditions and leisure pursuits of the local population or host community. It can include attendance at cultural events. visits to museums and heritage places and mixing with local people. It should not be regarded as a definable niche within the broad range of tourism activities. but encompasses all experiences absorbed by the visitor to a place that is beyond their own living environment.

Domestic Tourism generally refers to those who travel within their own country or region for pleasure. business, learning, holiday, recreation or to visit friends and relatives It Includes those who visit another part of their larger living environment, beyond the sphere of their daily lives.

Ecosystems means a dynamic complex of organisms their non-living environment, interacting as a functional unit.

Geodiversity is the range of earth features including geological, geomorphological, palaentological, soil, hydrological and atmospheric features, systems and earth processes

Heritage is a broad concept that encompasses our Natural, Indigenous and Historic or Cultural inheritance.

Heritage Collections include all of the moveable articles that may be associated with a place, an activity, a process or a specific historical event. They also include collections of related or unrelated items that have been gathered into museums. art galleries. scientific repositories. archives and libraries. both public and private.

Heritage Place describes a site or area of heritage significance that contains a number of buildings and structures, cultural landscape, monument, building or other structure, historic human settlement, together with the associated contents and surroundings or curcilage. Heritage places include those, which may be buried or underwater.

Heritage Significance recognizes both the Natural and Cultural Significance or important values and characteristics of places and people.

Host Community is a general concept that encompasses all of the people who inhabit a defined geographical entity, ranging from a continent, a country, a region, a town, village or historic site. Members of the host community have responsibilities that include governing the place and can be regarded as those who have or continue to define its particular cultural Identity, lifestyle and diversity. They contribute to the conservation of its heritage and interact with visitors .

Indigenous Cultural Heritage is dynamic. It includes both Tangible and Intangible expressions of culture chat link generations of Indigenous people over time. Indigenous people often express their cultural heritage through ‘the person, their relationships with country, people, beliefs, knowledge, law, language, symbols, ways of living, sea, land and objects all of which arise from Indigenous spirituality. Indigenous Cultural Heritage is

essentially defined and expressed by the Traditional Custodians of that heritage.

Intangible Cultural Heritage can be defined as embracing all forms of traditional and popular or folk culture, the collective works originating in a given community and based on tradition. These creations are transmitted orally or by gesture, and are modified over a period of time, through a process of collective re-creation. They include oral traditions, customs,

languages, music, dance, rituals, festivals, traditional medicine and pharmacopeia, popular sports, food and the culinary arts and all kinds of special skill connected with the material aspects of culture , such as tools and the habitat.

International Tourism generally refers to those who travel to another country for pleasure, business, learning, holiday, recreation or to visit friends and relatives.

Interpretation means all of the activities. including research, involved in the explanation and presentation of the Tangible and Intangible values and characteristics of an Historic Place, object, collection, or activity to the visitor or member of the Host Community.

Limits of Acceptable Change refers to a process of establishing the key values and characteristics of a place and the maximum extent to which they may change before the core of their importance is degraded to an unacceptable extent. Tourism and other activities can then be monitored or evaluated to determine the rate at which these values are threatened.

Natural Heritage consists of ecosystems, biodiversity, and geodiversity considered significant for the existence value for present and future generations in terms of their scientific, social, aesthetic and life support values.

Natural Heritage Significance means the Importance of ecosystems. biodiversity and geodiversity for their existence value or for present and future generations, in terms of their scientific, social, aesthetic and life support value.

Sustainable Future refers to the ability of an action to be carried out without diminishing the continuation of natural processes of change or damaging the long term integrity of natural or cultural environments, while providing for present and future economic and social well-being .

Sustainable Tourism refers to a level of tourism activity that can be maintained over the long term because it results in a net benefit for the social, economic, natural and cultural environments of the area in which it takes place.

Tangible Cultural Heritage encompasses the vast created works of humankind, including places of human habitation, villages, towns and cities, buildings, structures, artworks, documents, handicrafts, musical instruments, furniture, clothing and items of personal decoration, religious, ritual and funerary objects, tools, machinery and equipment, and industrial systems.

Tourism Industry encompasses all those who work in support, facilitate or provide goods and services to Domestic and International Tourism activities.

Tourism Projects include all of the activities that enable, facilitate, or enhance a visit to a destination, including the provision or upgrading of related infrastructure and facilities.

HPA Projects

About the Author

HPA is a leading design and project management company specializing in tourism, leisure and heritage projects. We provide a comprehensive range of services from concept and feasibility assessment, design development to implementation, contract management and delivery. We have over 25 years of experience managing projects internationally for private and government clients. Our diverse projects reflect the specialized field typically ranging between $1.S million to $50 million.

As principal contractor, design manager or project manager we bring together a broad range of expertise focused on innovation andimplementation.

Our Clients

Government and Institutional clients such as The Australian Government. The Qatar Foundation, The National Museum of Australia. confirm our experience in significant cultural heritage project development.

Corporate sector clients such as BridgeClimb Sydney, Real Journeys New Zealand, Subaru. and Toronga Zoo are testimony to our credentials in tourism development projects.

We are fortunate to have worked on some unusual and challenging projects having delivered successful complex assignments at home in Australia and in Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, Thailand and New Zealand.

Relevant Experience (Military Heritage Sites)

- lsurava Memorial. PNG 2002 (Design Construct Contractor)

- Hellfire Pass, Thailand 1998-current (Design and Construct Contractor)

- Sandakan Memorial Park, Malaysia

- Villers Bretonneux (Development Masterplan)

Relevant Experience (Cultural Heritage)

- Al Zubara Fort,Qatar (Development Masterplan)

- Jain Centre, Mumbai India (Site Development Masterplan)

- BridgeClimb, Sydney Australia (Site Tourism Development Contractor)

- Hermannsburg Historic Town, N.T. Australia (Site Development)

Natural Heritage Projects

- Taronga Zoo – Coastline Precent (Design Consultants)

- Lark Quarry. Winton (Design Consultants)

- International Antarctic Centre, NZ (Design and Construct Contractor)

Notes

Section 3 – Background – Page 7

Note I: Kokoda Track, Sustainable Development Pian, Scoping Study DroReport; TRIP Consultants. 2007. Kokodo Track, Pian (or Sustainable Tourism; The Kokoda Track Foundation, 2007. Ecotrekkmg. A Viable Development Alternative for the Kokoda Track?; S. Grabowski, 2007

Note 2: Second Joint Understanding,between Papua New Guinea and Australia on the Owen Stanley Ranges, Brown River Catchment and Kokodo Track Region; The Australian Government, Kokoda Initiative, 20I0-20I5

Section 4 – Kokoda – Page I I

Note 3 – Note 4 – Note 5

Ken Inglis had pioneered scholarly interest in the commemoration of war in Australia: ‘The Anzac Tradition: Meanjin Quarterly. I ( 1965). 25 44. Bill Gammage. The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War (Canberra 1971; repr. 1975 ) was important in stimulating increased scholarly and public interest .

The speech that Keating gave at Ela Beach is in Mark Ryan (ed .), Advancing Australia; the speeches of Paul Keating, Prime Minister (Sydney 1995). 279 82: and see Don Watson, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: a portrait of Paul Keating PM (Sydney 2003). 180- 4; and H Nelson. ‘Gallipoli, Kokoda and the Making of National Identity’,

Journal of Australian Studies, 53 (1997), 157-69 .

From the typescript issued by the Prime Minister’s office. Howard gave two speeches at Hellfire Pass on 24 April and one (quoted) on 25 April at Kanchanaburi .

Section 4 – Kokoda – Page I 2

Note 6 – Note 7 – Note 8 – Note 9 – Note 10 – Note 11

From the typescript issued by the Prime Minister’s office .

Nelson, ‘Kokoda: the track from history to politics’, Journal of Pacific History, 38 (200)), has examples of newspaper responses .

The Journal of Pacific History, Kokoda: and Two National Histiories; H Nelson. 2007.

Kokoda Track Authority. Website : Licensed Operators. Kokoda Track Authority. Website: Licensed Operators. Kokoda Track Authority. Website: Licensed Operators .

Section 4 – Kokoda – Pag e 13

Note 12 The Journal of Paciific History, Kokoda: and Two National Histories; H Nelson , 2007.

Section 4 – Kokoda – Page 15

Note 13 – Note 14 – Note 15 – Note 16 – Note 17

The Journal of Pacific History, Kokoda: and Two National Histiories: H. Nelson, 2007 The Journal of Pacific History, Kokoda: and Two National Histories; H.Nelson. 2007. Angau War Diary, table at the end of the Oct. 1942 diary.

Angau War Diary, table at the end of the Oct . I942 diary .

Angau War Diary, table at the end of the Oct . 1942 diary.

General Note – Track or Trail?

We have used Trail as it is the PNG gazetted term. However we have also aimed for consistency in the use of Track or Trail. Generally we have used Trail however with terminology such as ‘Kokoda Track Authority’ or where The Australian War Memorial cites ‘Track’, we have used Track.

References

Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs & Trade Papu New Guinea Minister for Foreign Affairs. Trade & Immigration. 20I0. Second joint Understanding 20I0-2015 between Papua New Guinea and Australia on the Owen Stanley Ranges. Brown River Catchment and Kokoda Track Region .

Berno. T. & Douglas. N. I998 , ‘Tourism in the South Pacific a Polynes, ‘a Melanesia discussion’, Asia Pacific Journal of Research 2 (2): 65-73.

Briguglio. L.. Archer . 8., Jafari, J. & Wall. G. (eds) I996, Sustainable tourism in islands and small states: issues and policies, Printer Press, London .

Bushnell. S.M. 1994, The ecotourism planning guide for ecotourism operators in the Pacific islands. College of Business Administration. University of Hawaii, Honolulu .

Butler, R. 1992, ‘Alternate tourism : the thin end of the wedge’, in Tourism alternatives: potentials and problems in the development of tourism. eds V.S. Smith & W.R. Eadington, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia· 31- 46 .

Cate r, E. & Lowman, G. (eds) 1994, Ecotourism: a sustainable option? Wiley. Chichester .

Department of Environment Sustainable Ltvelihoods.

Water , Heritage. and the Arts. 2009 Kokoda Livelihoods Project,

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) I 995. Guidelines on environmentally sound development of coastal tourism, United Nations, New York.

Farrell, B.H. 1992, ‘Tourism as on element ,n sustainable development’, ,n Tourism alternatives: potentials and problems in the development of tourism, eds V.S. Smith & W.R. Eadington, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia: 1 15-34 .

Farrell, B.H. (e d.) 1977, The social and economic impact of tourism on Pacific communities, Centre for Pacific Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Grabowski. S. 2007. Ecotrekklng: A viable development alternative for the Kokoda Track?

Harrison. D. 1992, ‘Tourism in less developed countries: the social consequence’, in Tourism and the less developed countries.ed. D. Harrison, Wiley, Chichester · 19-34,

Harrison, D. 200 Ib, ‘ Tourism and less developed countries: key issues’, in Tourism and the less developed world: issues and case studies. ed . D. Harrison. CAB International. Wallingford : 23-46 . Harrison, D. 2004, Tourism in Pacific Islands, The Journal of Pacific Studies.

Honey, M 1999, Ecotourism and sustainable development, Island Press. Washington DC. Howes. Prof Stephen . 20 I 0 , Review of the PNG-Australia Development Cooperation Treaty, 1999. Commissioned by Independent Consumer & Competition Commission (ICCC) and PNG Tourism Promotion Authority (PNGTPA) 2006, Papua New Guinea Tourism Sector Revtew and Master Plan (2007-2017) ‘Growing PNG Tourism as a Sustainable Industry’ Final Report.

Inglis. K.S. 1998. ‘Sacred Places’, War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. Foreword by DR Tom Frame, Anglican Bishop to the Australian Defence Force.

Inskeep. E 199I. Tourism planning: on integrated and sustainable development approach, Van Nostrand Reinhol d. New York.

Dr James. K. 2009 . ‘The Track’. A Historical desktop study of the Kokoda Track, Commissioned by the Department of Environment, Water. Heritage and the Arts. Military History Section, Australian War Memorial. Canberra .

Kokoda Track Foundation . 2004. A Report of Sustainable Tourism Workshop Efogi,Village, Kokoda Track.

Kokoda Track Foundation . 2004. Kokoda Track Sustainable Tourism Strategy and Action Plan. Interim Report.

Kokoda Track Foundation. 2006, Eco-Trekking Kokoda, A Plan for Sustainable Tourism (Apr 2006). Kokoda Track Foundation. 2006, Eco-Trekking Kokoda, A Plan for Sustainable Tourism (Jun 2006). Kokoda Track Foundation. 2007, Kokoda Track, Plan for Sustainable Tourism.

Kokoda Trust , SEP 2007. A Discussion Paper an the Kokoda Eco-Trekking Industry.

Laracy, H. 1994 , ‘ World War Two’, in Tides of history: the Pacific islands in the twentieth century, eds1 K.R. Howe. R.C. Kiste & B.V. Lal, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards. New South Wales: I 49-6 9

Laracy. H. & White. G. (eds) 1998 , ‘Taem blong foet: World War II , in Melanesia’, ‘O’O Number 4 (Special Issue) .

Liu, J.C. I 994. Pacific islandsecoiourism: a public policy and planning guide, College of Business Administration. University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Martel, F. 2000. ecotourism in conservation areas of the Pacific islands. Summary for the WTO/UNEP conference on sustainable tourism in Asia-Pacific islands, Sanya , Hainan, China. 6-8 December .

Mason, P. & Mowforth, M. I995 , ‘Codes of conduct in tourism’. Occasional papers in Geography. I. Department of Geographical Sciences. University of Plymouth, Plymouth.

McDonald, M & Wearing. S. 2002, The Development of Community based Tourism: Re-thinking the Relationship Between Tour Operators and Development Agents as Intermediaries ,n Rural and Isolated Area Communities, Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

McVey. M. 1995. a Papua New Guinea: tourism sector review, Tourism Council of the South Pacific, Suva .

McVey, M. I995. Niue: tourism sector review, Tourism Council of the South Pacific. Suva . Mowforth , M. & Munt. I. I 998, Tourism and sustainability new tourism in the third world.

Routledge, London .Neale. G. 1998, The green travel guide, Earthscan. London . Nelson, H. Gallipoli, Kokoda and the Making of National Identity.

Nelson. H. 2007. Kokoda: and Two National Histories. The Journal of Pacific History, 42· I. 73-88

Pearce. D.G. 1995. ‘Tourism 1n the South Pacific: patterns, trends and recent research’, Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research. I: 3- 16 .

Ranck. S.R. 19 87 . ‘An attempt at autonomous development: the case of the Tufi guest houses, Papua New Gumea’, in Ambiguous alternatives: tourism in small developing countries, eds S. Britton & W.C. Clarke, The University of the South Pacific. Suva: 154-66 .

Rudkin , B. & Hall, C.M . 1996, ‘Unable to see the forest far the trees: ecotourism development in Solomon Islands’, in Tourism and indigenous peoples, eds R. Butler & T. Hinch, International Thomson Business Press. Lon don: 202-26.

Russell. D. & Stabile, J. 2003 , ‘Ecotourism in practice: trekking the highlands of Makira Island, Solomon Islands’, in Pacific Island Tourism, ed . D. Harrison. Cognizant. New York: 38-57 . Scates. B. 2006. ‘Return ta Gallipoli’, Walking the Battlefields of the Great War.

Senate Meeting of Environment. Communications and the Arts Legislation Committee, 2009. ‘Kokoda Track Code of Conduct’, Department of Environment. Heritage , Water & The Arts (Oct 1009).

Senate Meeting of Environment and Communications Legislation Committee, 2009. ‘Protection of Kokoda Track & Owen Stanley Ranges’, Department of Sustainability. Environment. Water, Population & Communities (May 20II).

South-Pacific Travel, 2007 . Marketing and Developing Tourism in the South Paci fic, 2007 Annual Report.

Thomson, A. 1996 , ‘Tourism: prospects for the year 2000 and beyond’, in Economic prospects for the Pacific islands in the 21st century. ed . R. Grynberg , School of Social and Economic Development. The University of the South Pacific, Suva : IO1-1 I.

Tourism Council of the South Pacific (TCS P) 1988. Nature legislation and nature conservation as a port of tourism development in the islands and Pacific. TCSP, Suva.

Tourism Council of the South Pacific (TCSP) 1990, Vanuatu: evaluatlon and development needs, Tourism Sector Report, TCSP. Suva.

Tourism Resource Consultants (TRC) I 999, Report on the Pacific Ecotourism Workshop, Taveuni. Fuji Islands, 28-31 July. TRC, We llington .

TRIP Consultants for IFC PEP- PACFIC, 2007. Kokado Track, Sustainable Development Plan, Scoping Study. Draft Report

Wahab, S. & Pigram, J. (eds) 1997. Toumm, development and growth: the challenge of sustainability. Routledge, London .

Weaver. S. 19 92. ‘Nature tourism as a means of protecting indigenous forest resources in Fiji’, Journal of Pacific Studies, 16; 63-73 .

Wheeller. B. 1993. ‘Sustaining the ego’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism I (2): 12 1-9.

World Tourism Organization (WTO) 1994 , National and regional tourism planning: methodologies and case studies, Routledge . London

World Tourism O rganization (WTO) 200 I a. Compendium of Tourism Statistics: 200 I Edition , World Tourism Organizat ion . Madrid.

World Tourism Organization (WTO ) 2002. Compendium of Tourism Statistics: 2002 Edition. World Tourism Organization. Madrid .

Worsley. P. 1968 , The trumpet shall sound . a study of ‘cargo’ cults ,n Melanesia, 2nd edn. MacGibbon & Kee, London .

Ross Bastiaan is a Melbourne peri-orthodontist and senior Royal Australian Army Dental Corps officer. Frank Taylor is a Western Australia senior police officer and Army Reservist; they installed Ross’s magnificent bronze plaques along the Kokoda Trail in 1992. Their work was funded by Hugh Morgan of Western Mining Corporation. Frank installed 2″ diameter gravity-flow plastic waterpipes into Menari, Kagi and Naduri villages in previous years. Ross featured on “Australian Story” some years ago; his plaques commemorate military and civilian endeavour in numerous places throughout the world. Along the Kokoda Trail and elsewhere in PNG they have both English and Tok Pisin text; the large plaques display the Trail as a terrain model in a three dimensional bronze casting. The angular steel arches at Owers’ Corner and rounded steel arches at Kokoda (hence the “Macca’s” tag) were installed by Eric Winn, a Vietnam veteran and others some years ago. Bolted in place, the arches can be moved if necessary; they display small plaques listing all of the AIF units which served on the Kokoda Trail. The arches are crowned with the AIF ‘Rising Sun’ badge and group photos provide proof that trekkers have walked the Trail. The plaques have occasionally been vandalised; the RPNGC (police) can quickly identify the culprit; funding can then be found allowing Ross to make replacement pieces and volunteers reinstall them.