The Rise, Fall and Future of Kokoda Tourism

The Canberra Times

Marion Frith

15 November 1992

“WE ARE indeed a strange collection of life’s assorted gathered here so far from home, checking our packs, checking out each other. Among us are the media’s most unfit, a professional fisherman, a surgeon-cum-ardent bushwalker, a marathon runner and a 70-year-old war veteran. We are on a pilgrimage for which, it turns out, we are largely unprepared“.

Marion Frith reports:

‘The Owen Stanley Ranges loom before us and it seems unfathomable as we bask in the sunlight at Ower’s Corner that we are about to tackle them. New gaiters, new boots, and a newfound sense of adventure. They won’t be enough – but we don’t know that yet. Nor do we really know just how tough “the bloody track” will be.

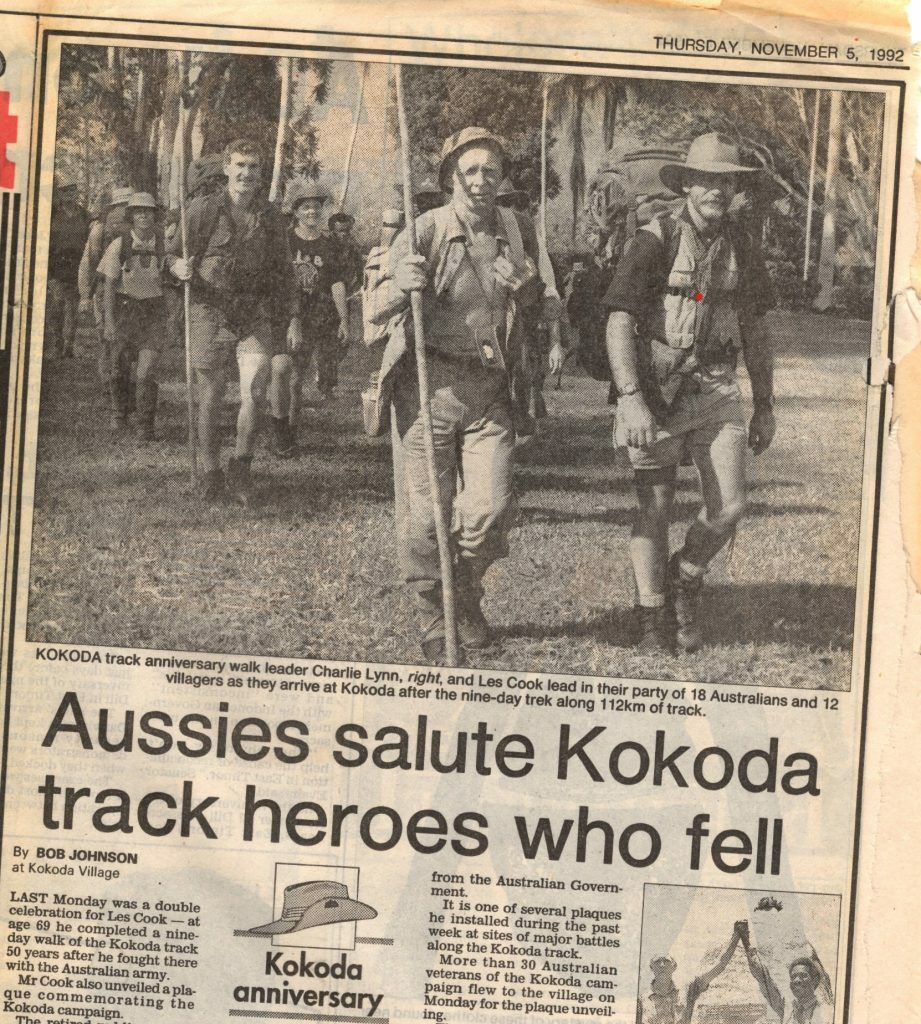

‘Our reasons for being there are many: some of us have been lured by the historical significance on this the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign, others by the challenge of a “walk” (ha!) regarded as one of the most difficult in the world, and I and one other are retracing the awful steps taken by our fathers before we were born. Les Cook, of Garran, a veteran of the bitter battle, is there because, he says, he could not pass up the chance to come back and see it one more time.

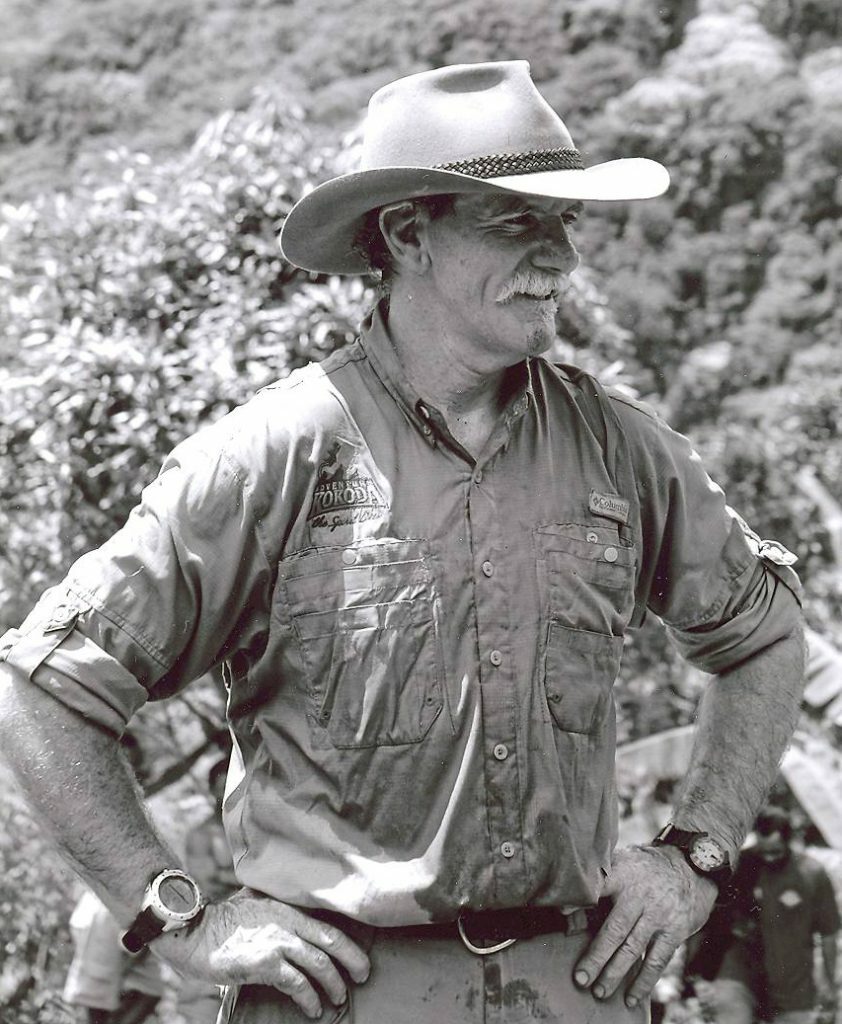

‘We have been herded together by an extraordinary man, Charlie Lynn, a retired Army major, who runs a company called Kokoda Epic. He is a passionate blend of adventurer and zealous patriot with an encyclopedic knowledge of the Papua-New Guinea campaigns and an unswerving commitment to enshrining Kokoda and all it represents in the minds and hearts of ignorant Australians.

‘He stands before us, a rugged Ken-doll lookalike, and immediately we respect and trust him. We also like him, some come to revere him, even though during the next eight days fond feelings are hard to access – “I hate you Charlie” echoes pitifully through the valleys – as he psychologically cattle-prods us through the worst of a physical nightmare that only becomes wonderful in hindsight.

‘Between Charlie and Les the horrendous jungle track and the war which raged so viciously across it come to life. Charlie’s moving accounts are coloured with Les’s lively recollections. “This is where the Australians were butchered in their pits,” Charlie will say. “My mate lost his last tin of rations down that hill,” Les says. And together they guide us for a week through a moment in history that shaped a generation and cost it its innocence.

‘WE SET off eager and happy and almost at once a circus of dancing butterflies descends – yellow, blue, pink and purple. They hail our arrival and farewell us later. They land on our packs and distract us from the track that is gruelling from the outset.

‘By lunch we are exhausted and we rest by the Goldie river. Already blisters are erupting on tender feet and muscles are stabbed with searing pain. Then it is the infamous Golden Staircase, where thousands of small logs, now rotted away, were pegged by Australian engineers to mark the Ridge. We get to the top only just, shattered and drained.

“’That’s just a speed hump,” Charlie laughs, as we stand stunned with disbelief. The Adventure – and Charlie’s perpetual frustrating dismissal of our very real despair – has begun.

‘It is many, many hours later and long after nightfall that we lurch into camp after negotiating the slips and slides of rocky creekbeds and sharp, muddy inclines. The air is still heavy, the rain still drizzling and all night I have nightmares and terrifying attacks of panic that send me thrashing out of the claustrophobia of my tent and into the steamy unfamiliar jungle clearing.

‘I have no doubt that I have made a terrible mistake by coming here, a sentiment shared by most of the others, triggered by the realisation that there are still 100km and a dozen mountains ahead.

‘NEXT morning the as-yet-uncrumpled map sprawled out among the muesli, tea-bags and dew show two very steep climbs ahead of us; the first up past the old village of Ioribaiwa and the second over the Maguli Range. In my soon-to-be-shattered naivety I look at the black outline of the peaks and drops with the enthusiasm and optimism that comes with a new dawn.

R’ight, I think. Off we go then, let’s get this out of the way. Again, and at once, it is tough going. My legs are still aching from the day before. I stumble off a rock and into the creek as we leave camp and my feet are wet and soggy for the rest of the day, simmering and steaming as the oppressive heat descends. We pass out of the jungle and through stretches of barbarous kunai grass which scratches and cuts. It is awful and I want out. There is no our, however, bar the one you walk to. So dream on. Trudge on.

‘By lunch we have six hours of trekking behind us. Six hours. I collapse beside the creek and do my best to wash the green dye from my feet, a legacy of new socks. But the green is set, the base colour in what proves to be a rainbow of indelible new-sock hues. All this pain, and green feet. Please can we stop for the day? I have had enough, Charlie. But Charlie is rallying reluctant troops who are pulling themselves up with poignant despondency.

‘And so begins the Horror Afternoon, the first ascent of which is a couple of hundred metres of muddy verticals. I begin the clamber, clutching at tree roots and clumps of grass as the creek falls away behind me. I am terrified. I freeze and let out my first non-leech induced scream. I am unable to move, my body is frozen with fear and within seconds one of the guides has scrambled up the glassy rise beside me.

‘His bare feet cling to the cliff like suction cups, his hand takes mine with a grip so strong I swear it will crush my fingers. He pulls, and I manage to move an inch. Slowly he guides me up and over the worst. The other guides watching from below laugh hysterically. My tenuous confidence is shattered. I am scared.

‘Still, there is no out. Only up. Up, up, up. The jungle floor is slippery and I can not afford to take my eyes of my feet – when I do I trip. I am concentrating so hard my head is pounding. Hours pass and then suddenly the sky looks through the foliage. My heart races. The top. We are at the top. A few more metres, nearly there. And then the track swerves to the left and the jungle mocks as it will mock me a thousand times. It is a false peak, nature’s cruellest illusion, and still it is up.

‘The pack of us that has fallen to the back of the group are slow and suffering. We stop constantly, cramping and aching. When will it end? By late afternoon it is raining steadily and we have not even made the ascent: there is a long way to go. Night begins to fall, as do my tears. Charlie steadies me with a cuddly and some food. “Come on mate,” he says. “You can do it.” But I don’t want to do it and I don’t want to be there. I want to go home.

‘Still we creep on. We are blanketed in darkness and lonely torches compete with armies of fireflies beneath a thick jungle canopy that censors any hope of starlight.

‘The “up” eventually becomes an equally horrendous down and we put nervous muddy boot after nervous boot, conscious that every step has the potential for injury. Where does our energy – pathetic and all but spent – continue to come from? How is that we are able to move at all? Still, the camaraderie that descends upon this miserable caravan of lost souls is warm and enveloping. Those with torches light the way for those without, those temporarily firm on their feet support those who continually fall, those still able to muster a meagre dose of fleeting good cheer share it round in exchange for a last morsel of chocolate.

‘One of our lot comes to a standstill and begins to vomit uncontrollably, so racked is his body. We stand dumbly by, waiting for it to pass, then without words we move on. We are a team, a wet and frightened one, but a team. Friendships begin, loyalties become established. We are in this, for better or worse, together.

‘Finally, almost 16 hours after we set off that morning, we reach the village that is camp for the night. Charlie shepherds us in, he is tense and concerned. He had not reckoned on us being this bad. I collapse beside the fire, sobbing and shaking. My body is in spasm and I hear the nurse in the group mutter something about shock.

‘Suddenly tender hands that just 24 hours ago belonged to strangers are upon me, pulling off wet clothes, finding dry ones, holding hot tea to my lips and pressing a bowl of warm mush into my hands. Someone has laid out my sleeping mat, someone else is quietening the fast swelling number of hysterical pledges to pull out. As a group we are close to being out of control. We have lost it.

‘My last words for that awful day as I lie in the eerie darkness that characterises the middle of nowhere later become enmeshed in trek folklore. “I know we’re here, Charlie, “I cry as the awesome silhouettes of unfamiliar mountains rise around us. “But where the f— is here?”

‘INCREDIBLY I am not broken – just broken in – and I wake to find that the despair of the night before has evaporated into the mist hanging over the valley. A group of solemn-faced children have put themselves on sentry duty by our camp and a newborn baby, her head kissed with the first buds of tight black curls, lies in her shy mother’s arms.

‘We gather around Charlie to discuss the horrors of the night before. Today, he promises, we will stop and pitch camp at 4pm – no matter what. No night trekking. Still, some of us are sceptical and close to admitting defeat. There is a village we should reach later in the day which has regular visits from a light aircraft. Today, out is a possibility. One of us at least has decided to definitely to take it.

‘The rest of us will see how we go, and for the first hour or so the countryside does its best to woo us as we snake through paradise-like village gardens and cross crystal rivers and rickety log bridges. The idyll is short-lived and by mid-morning we are once again entrenched in the see-saw of sickening climbs followed by hairy descents. Psychologically, however, something has shifted within most of us. Our whingeing has waned.: we know we do not actually want to give up. If we survived the day before we can survive anything, and our bodies are spurring us on by proving they have purged themselves of the worst of the pain.

‘We never stop hurting, but few of us hurt like we did and a numbing exhaustion gradually replaces the jabbing pangs. One hundred kilometres through dense jungle? We are now really aware of just what that means, of just how hard it will be, but we are also aware that if we want to do it we probably can, it is up to us. There are things we need to call on from within ourselves – grit and determination, Charlie calls it – and things we need to draw on from the group – support and friendship – in order to meet the challenge. But this morning the commitment is sealed in sweat. From this point on, all but one of us will never doubt again that we will do it.

‘We arrive at the village of Menari after lunch, a break of swimming and laughing and two-minute noodles. This is where the photographer who has decided to call it quits is to leave us. An incessant and mournful wailing greets us as we enter the village: a little boy has just died of cerebral malaria and a woman is sitting outside her hut cradling his body as her cries ricochet hauntingly through the valley. We are quiet as our fellow trekker stumbles into the guest house, fatigued and weak.

“Like our own funeral,” a guide says in faltering English as we all turn for one last wave to our friend. And it is. One down . . . no-one wants to keep counting.

‘The sun is high and the rugged country-side stretches before us as we leave the village and its sadness behind us. Its iridescent green collides with the blue of a perfect sky in the black slug of the mountains. My impromptu rendition of Climb Every Mountain is met with howls, as it is every other time I am tempted to break forth. But our spirits are up, morale is soaring. It is a wonderful feeling.

‘We pitch an early camp. Our guides, also lightened by the easier day, are cheerful. Charlie looks relieved and someone breaks out a waterbottle full of rum. A mere 8km of hard trekking and we are already dismissing it as a breeze of a day. A few days ago 8km might as well have been 800. Our tolerance and our fitness are increasing. We are Doing it. We are crossing the Owen Stanleys. We are on a high that threatens to rob us of the memories of the day before. I fight it. Don’t get cocky, something says inside. Don’t ever forget.

‘The next day we walk and walk, up one of the toughest rises yet, down some of the worst. We try to stop quantifying. What is worse, anyway? All the climbs are mongrels and even on a good day there is nowhere I ever want to be except out of there. But something keeps us going, keeps us dragging foot after foot. Every step completed is one that never has to retraced. Up, down. Up, down. Around, across. Up, up, up.

‘That afternoon we reach our nirvana – the village of Naduri. It is the home of our guides and we arrive to a hero’s welcome. Les leads us triumphantly in and we are met by the village elders – the original war-time “fuzzy-wuzzy angels” who carried the injured Diggers out against all odds down dangerous narrow mountain tracks. A feast of food and flowers is laid out for us: mandarins, sugarcane, baked and steamed taro, pumpkin tops, potatoes, spinach.

‘We fall quiet as these old men stand tall and proud. Charlie seizes the moment, the women and children are banked up around, and in a gesture that cuts across cultures and through language barriers he recites the poem that immortalised these angels. The old men beam, and our army of trekkers wipe away tears.

‘It is as if we have arrived. Somewhere, anywhere. Our guides sit with us, their families join us, and the village and its people become imprinted in our hearts. Another woman and I join the evening church service and are entranced as the pastor, his face illuminated by a hurricane lamp, recites the prayers in pidgin and the children’s voices rise in harmony so sweet we never want it to end.

‘We are silent as we get up from the rough-hewn pew. At that moment we have experienced life at its most perfect, superb in its simplicity, and suddenly we realise that the walk was worth it, if only to find this. Peace and joy are tangible, if fleeting, qualities and we know that where we are going to, where we have come from, we will probably never find it again. We want to seal the village in barbed wire and never let the world touch it.

‘But instead, of course, as travellers everywhere, we move reluctantly on. We walk next day for hours through an eerie moss forest, each of us alone for most of it as the group disperses at different paces. We cross the lake Flats to the village of Myola and its primitive guest house, stopping on the way to collect bullets and ammunition abandoned by the Australians. We are reminded yet again that that this quiet, hostile, landscape was witness to bloodshed and merciless death, and, for the umpteenth time, I become my father’s daughter trying to grasp something of the circumstances that shaped him into a sad and lonely man.

‘We drag into the guest house, stinking and filthy. Some try to wash putrid socks in a sparkling stream, others wash foul bodies in our first shower of sorts, courtesy of a suspended plastic bucket. This is five-star stuff such as we would never have dared dreamed of – there are even beds, good food, bread. Temporary bliss. We pick up new supplies only to find they have been stored with drums of kerosene. Every bit of food is tainted, reeking of the stuff, and the challenge becomes whether to eat nothing and faint, or eat, and be sick. Someone finds a few packets of biscuits that are okay and it is like Christmas. From here on we are very low on any form of comfort.

‘We have tackled the trek from the hard end. Most pilgrims head south, making their first few days relatively easy – though still not “easy”. But we have faced the worst first, taken the toughest climbs when we were unacclimatised and at our most unfit. Still, the last couple of days become vaguely downhill and we continue to trek all day, day after day, stopping to bathe in mountain waterfalls, swim in icy creeks and take in spectacular views. We have little doubt we have experienced paradise but even so we want it to end. Bodies and minds are packing it in, and sprains, pains and irritabilities are mounting.

‘When we finally enter sleepy, tiny Kokoda, drenched in sunshine, we are surely as triumphant as the troops who re-entered it that same morning 50 years before. We assemble at the commemorative ceremony, attended by a lowly Australian Government minion and a handful of veterans and as the Last Post sounds pitifully on a crackling portable tape recorder we are truly moved. We have done it. We understand as only those who have done it can. Our peace-time journey has tested and pushed us as we could never have imagined. The silent respect we pay to the young men who served and suffered along the path we have crossed is deep.

‘As we clamber aboard the truck that has come to take us to the airport we have no doubt we are now invincible. We have plummeted to our worst lows and soared to our greatest heights. There is nothing physically or emotionally we cannot endure. We had set off as 34 individuals, half of us Australians and half of us Papuan villagers. When we part we are friends – an indivisible and strong unit for whom farewells come hard.

I’f the spirit of Kokoda is strength in adversity, courage and mateship that spirit has been seeded in us all. We cross in a brief 20 minutes what has taken us eight gruelling days. And like all those who crossed it before us, who left their souls in the mud and the heat and the terrifying jungle, few will ever go back.

‘Charlie, of course, is the exception. He will continue to pluck other ordinary humans from their comfortable lives and help them blossom into indefatigables, drawing on the greatness that lies largely unchallenged within us all. For the rest of us though, Kokoda will become just one humbling week in our lifetimes: albeit our whole lifetimes lived in just one unforgettably humbling week.‘

Marian Frith

The Canberra Times Sunday

November 15, 1992

Corporal Les Cook enlisted with his father into the Army in 1940. To be able to enlist, both lied about their ages. His father put his age down by four years, and Les put his up by four. Les was in fact just 17 years of age on enlistment. Les served with the 2/14th Battalion in North Africa, Papua including Kokoda, New Guinea and Borneo. He also served as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan.

The Australian War Memorial hosted Corporal Les Cook at the Last Post Ceremony on 22 July 2022 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the Kokoda trail campaign.