by Rashmii Amoah Bell

‘ I am the author of ‘My Walk to Equality’ and Butterflies on Kokoda as well as numerous essays for Pukpuk publications.

‘I recently participated in a trek across the Kokoda Trail with Adventure Kokoda.

‘I was informed that I had free reign to talk to trekkers; local guides and carriers I met during our trek; campsite owners; and villagers along the trail as part of my research for future articles on my experience.

‘As a Papua New Guinean citizen, I am conscious of contributing to and engaging in dialogue that strives to positively impact nation-building activities, facilitating only the well-being and realisation of the full potential of the indigenous people and our land.

‘I was shocked at what I witnessed during my trek across the trail.

‘I thank Keith Jackson for publishing the series of articles I wrote in his widely acclaimed ‘PNG Attitude’ blog.‘

ON THE TRAIL – In 2017, I was invited by the Australian-based social enterprise, Kokoda Track Foundation (KTF), to facilitate two rural school book-making workshops in Oro Province.

While designated to act only in as a volunteer, all research, design, delivery and facilitation was assigned to me by the Foundation. On both occasions I achieved the assigned outcomes.

And so, having donated my time and talent to this organisation, it was with disappointment and regret to have it deny my sole and rightful authorship of ‘Butterflies along the Track’, the KTF’s Kokoda75 commemorative children’s book, funded by Australia’s foreign affairs department.

Exacerbated by KTF’s resistance to engage in public dialogue (nor to issue a formal apology) on this matter, my frustration increased at witnessing what I perceived as a conscious act of perpetuating the ‘aid-dependent’ narrative of many projects in PNG.

Perhaps such strategies to insert oneself between aid funder and aid receiver are necessary for institutional survival masked as making a contribution to nation-building activities in PNG.

This incident shifted my attention to examining other activities of foreign entities in PNG. I was particularly on the lookout for acts of exploitation and dispossession of Papua New Guineans, especially in the rural and remote regions.

I saw an urgent need to critique the operations of such entities and the networks in which they function and benefit, specifically alert for activity directly affecting sustainable development, especially for girls and women.

It is this kind of advocacy that underpinned the nomination of the ‘My Walk to Equality’ literary project as PNG’s entry for the 2018 United Nations Girls and Women Education Prize.

So when Charlie Lynn OAM OL penned the scathing article ‘Losing Kokoda’, in Australian Spectator, it captured my attention.

A former Army officer, Australian state parliamentarian and long-time friend of PNG, Lynn has been consistently vocal about the importance of nurturing positive, people-to-people relations between Australia and PNG.

His trek company, Adventure Kokoda, has had a 27-year relationship with communities along the Trail, which he has walked no less than 93 times. Lynn’s commentary was deeply concerning.

The article was another chapter in Lynn’s efforts to highlight his observations of mismanagement and questionable operations of the Kokoda trek tourism industry. Most alarmingly, his commentary raised instances of exploitation of carriers by trek tour operators (many Australia-based). These could be seen as conscious acts of dispossession hindering the development of Papua New Guineans.

Lynn’s accounts illustrate a most troubling scenario, seemingly fostered by a defunct management body and its affiliated Papua New Guinean and Australian agencies, unable to properly discharge its mandated responsibilities including regulating trek operators, overseeing the distribution of benefits and ensuring the continued wellbeing of the Trail’s people.

As a Papua New Guinean who writes and publishes the writing of others to advocate social change, I sought on my own trek to observe first-hand, report and critique such disturbing claims. So I initiated contact with Charlie Lynn.

I was heartened when he responded by encouraging me both to undertake my first trek of the Trail as an investigative exercise but also to be immersed in an experience (regarded as akin to a pilgrimage especially by Australians) that many people had done before.

Lynn suggested I trek with Adventure Kokoda’s annual Kokoda Youth Leadership Challenge (KYLC) group; a 16-member team of young and open-minded Australians from NSW RSL Clubs.

For 10 days I lived with and walked in comradeship alongside 16 Australians on the soil that is my homeland, all of us retracing the steps of the brave men who 75 years ago fought to ensure the freedoms that we near neighbours enjoy today.

With the immeasurable aid of Adventure Kokoda’s team of carriers, guide ‘Big Joe’ and leader Charlie Lynn, we trekked the ever-changing environment along the 138 kilometres from Owers Corner to the Kokoda Plateau.

My own steps were observed closely and guided by De, my personal carrier, who became my lifeline in a setting that swiftly reveals weaknesses, demands unimaginable endurance and is unforgiving of a missed step.

I observed, interacted and listened to the lived experiences of those at the forefront of Trail tourism: the guides, carriers, campsite owners and people living in the villages along the way – all of whom should share the benefits generated by the tourism occurring around them.

I saw the ‘Spirit of Kokoda’ unfold in the individuals of my trek group and the Papua New Guineans in the villages en route. I noted that my positive interactions and ease of access with the people along the Trail was enabled by the long established rapport Adventure Kokoda carriers had established with the communities.

It caused me to consider that whilst Papua New Guinean and Australian bureaucracy muddles its way through strategies to strengthen bilateral relations and improve people-to-people relations, strong relationships are an absolute necessity on the rugged Trail where the Koiari and Orokaiva people have long resided. Seemingly, strengthening relationships it is the only way Kokoda Trail trek tourism will survive.

For trek tourism to thrive, the Kokoda Trail’s management body (including affiliated Papua New Guinean and Australian agencies) have an immense amount of work to do with trek operators, their employees and communities.

Some of the issues raised in discussions whilst I was on the Trail that I’ve submitted through a formal PNG channel include:

- erosion, particularly along steep mountain climbs

- lack of safety measures along the Trail, including safe and secure footbridges and a reliance on guides to construct temporary rope handrails

- disjointed support and communication by operators for trekkers and indigenous communities

- the inconsistent presence of rangers to monitor carriers’ pack weights

- limited access to safe, hygienic and secure amenities for trekkers; on several occasions Australians trekkers opted to ‘go bush’ instead of using the dismal pit latrine and other facilities available

- absence of structured promotion to engage and educate trekkers of the Koiari and Orokaiva people’s cultures

- community concern about disjointed engagement, infrastructure provision, program implementation and service delivery by Kokoda Track Authority, Kokoda Initiative and smaller non-government organisations

- the inequitable and blatant imbalance of the benefits between trekkers and trek operators and the indigenous staff and trail communities

- the marked imbalance of participation by indigenous women in comparison to that of indigenous men throughout the trail’s tourism activities and its offsets

- the breakdown of service delivery intended by the PNG and Australian governments and affiliated organisation for communities and lack of responsiveness the Kokoda Track Authority and Kokoda Initiative to suggestions from community members

- inconsistencies in the working conditions of carriers between the well-equipped Adventure Kokoda personnel and other tour operators including terrain-appropriate enclosed footwear, safety wear, adequate sleeping equipment and uniforms

At the core of this series of articles is a demand for responsible, ethical tourism ensuring professional support and strict regulation of operator activity to create a safe and satisfactory experience for trekkers and the well-being of the Papua New Guineans working on the Trail.

It is apparent that the Trail’s management body, including its network of affiliated Papua New Guinean and Australian agencies, needs marked improvements in its operations including enabling transparent dialogue with and accountability to all who access the Trail.

Disregard and Mismanagement Blight on Iconic Trail

A hand-built and much weathered column table flanked by snake-length benches sit on the earthen floor. Seated across from me in the candle light are three Papua New Guineans: one from Kokoda Initiative (KI) funded by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs; the other two from PNG’s Tourism Promotion Authority (TPA).

To my left is Adventure Kokoda trek leader Charlie Lynn and, at his suggestion, our trek guide and my carrier, DE. The sound of Brown River, in which I had bathed earlier, echoes around us.

TPA and KI are just two of the multiple agencies involved in joint PNG-Australia management of the Trail. Their overnight stay at the same campsite as Adventure Kokoda is an opportune encounter since our respective departures from Owers Corner.

In Agulogo, we are deep in the reality of the trek tourism industry. Out here our unfiltered dialogue is a welcome contrast to the characteristic theoretical musing and roundtable bureaucratic chat of Port Moresby.

The agency staff are undertaking campsite checks and we exchange our assessments of the current state of the Trail’s tourism activities.

We agree about the rapidly declining physical state of the Trail but the staff are visibly uncomfortable when management’s effectiveness is critiqued. From my side of the table, frustrations are aired about the lack of community participation in Trail tourism, especially by women and girls.

The KI person quizzes Charlie for his suggestions on campsite improvement. Charlie pauses for thought and the ensuing lull allows me to ask a question weighing heavily on my mind.

Turning to TPA staff, I enquire how tourists are encouraged to walk the Trail? What words, what imagery are used? I’m told it’s the story of the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’.

I struggle to contain my irritation.

SINCE first stepping on the Trail, I have observed nothing to indicate an effort by TPA to acknowledge, preserve or commemorate the 49,500 Papua New Guinean men who, using crude stretchers, assisted Allied forces by carrying to safety injured and wounded troops during the Kokoda battles of World War II.

I have seen no form of tribute through statue, monument, memorial garden or simple information board solely dedicated to the contribution of those carriers.

And I have a fast-growing list of concerns about the disregard shown to today’s carriers, including an absence of safety measures in the hazardous work environment, poor sleeping quarters at campsites and the lack of en route storage to minimise the weight of the packs they carry.

The PNG Tourism Promotion Authority draws international tourists on the basis of wartime history and yet, 76 years on, there is little to acknowledge or improve conditions for the men who, as did their predecessors, guide those who walk the Trail.

The TPA staffer responds, her words slow and considered as she describes that, like me, this is her (and her male colleague’s) first time on the Trail. Her voice breaks as she reflects on my concerns about the carriers.

Tears rolling down her face, she expresses concern and a deep sorrow at having witnessed the unnecessary harsh realities the carriers endure. It is the one thing on which we are in open and mutual agreement.

IN two days, the agencies’ personnel will end their trek at Kagi village, from where a charter flight will return them to Port Moresby.

We in the Adventure Kokoda trek will continue for another seven days to Kokoda. My guide DE’s warm comradeship will enable me to speak to the guides and carriers of other trek operators who we pass on the Trail. And, as we enter villages, DE’s facilitation allows me to have brief discussions with the people.

I am fortunate to have this conduit to the village people’s personal accounts, feedback and concerns with trek tourism. The first-hand information is crucial in any assessment of the impact, issues and benefits from the tourism occurring in their front and back yards.

In hindsight, I puzzle as to why the agency staff had not mentioned the inclusion of carriers as facilitators for their field work. DE has highlighted for me that carriers are integral to bridging communication between trekkers and the communities they meet along the way.

The carriers could play a similar role in communication between Trail communities and management. But this opportunity has been overlooked – or, like the best interests of the carriers themselves, perhaps disregarded.

THE recorded sound of a bugle from the direction of Charlie’s tent slices through the pre-dawn silence, a cheerful morning reveille – ‘wake up!’.

It’s the third morning of the trek and we’re at Ofi Creek; the site of a successful Australian ambush in World War II. We passed through Ioribaiwa village the previous day and the previous 24 hours have been themed with bouts of gruelling climbs overlayed by a scorching sun. Finally, there was a steep 35-minute descent into camp and the soothing cool of a creek.

The campsite itself is nestled atop a small hill. On this morning its manicured lawn are illuminated by the lights inside Adventure Kokoda’s orange tents. Some tents remain unlit as trekkers continue to sleep off the previous day’s fatigue. Eventually I stretch out my hand to reunite with my headtorch.

Bleary eyed, I unzip the tent’s two screens and peer out into pitch black. I heave my main backpack and smaller backpack onto the damp grass. Days before, at our departure point, I had weighed both in the presence of my trek mates. Adventure Kokoda insists trekkers carry their own backpacks which are limited to 12 kilograms. If you opt for a personal carrier, the pack is restricted to 18 kilograms.

Mine weighed in at 9.5 kilograms, so there was ample capacity for my carrier to add his personal belongings, a sleeping bag and a mat.

As early as the first day of the trek, I would come to understand why Adventure Kokoda’s continual advocacy for the 18 kilogram weight restriction for all carriers is a necessity for ethical and humane tourism.

MY tired feet slide into sturdy, well-designed sandals and my attention turns to the purposeful footsteps with which I have become familiar. Many more will be required this day.

DE arrives outside my tent in his usual quiet manner and, guided by a head torch, swiftly moves to rearrange my backpack to include his belongings.

I crawl out of the tent, rolled sleeping mat in hand but sleeping bag unravelled, and exchange morning greetings, sheepishly motioning to the remaining contents of my tent. He grins and takes the rolled mat from me and motioning to my smaller backpack, a reminder to leave out the hydration bladder and water bottle for him to refill from the creek.

Having suffered enough of my repeated clumsiness, DE has relegated administering the water purifying solution to my abbreviated short list of morning tasks.

Now in the tent to wrangle my sleeping bag, DE leans out and advises me to keep my sandals on. After breakfast, our group will make a short walk through the waters of the creek before beginning the grinding climb to the Maguli Range.

He tells me that, after packing my tent, he will take both backpacks and my hiking boots and meet me on the other side of creek.

Farewelling DE, I place some mocha sachets on his uniform cap and head toward the source of the wafting aroma of freshly brewed Goroka coffee and the hot breakfast being prepared by the trek group’s Boskuk.

IN early 2017, carrier Winterford Tauno died on Ioribaiwa Ridge.

He was employed by an Australian trek tour operator and it was reported that, despite instructions by a ranger, Tauno’s backpack remained overloaded. No investigation nor corrective action was demanded of the trek operator. Nor have I observed any monument for Tauno’s service.

It saddens me that the life of a Papua New Guinean of our generation could be so soon forgotten by the management that benefited from his service to commemorate the lives of those generations who served on the Trail before him.

GUIDE and carrier DE has been my lifeline on the Trail.

Just into his thirties, his lineage is from both the Koiari and Orokaiva sides of the Trail. As we trek, I listen to him weave in out of conversations in Motu and his mother’s tokples as he chats with fellow carriers.

Speaking to me, he opts for English, occasionally switching into Tok Pisin to draw the attention of other carriers to my awkwardness with the outdoors.

Unaided by safety measures like handrails or timber steps, our steep descent from Owers Corner on the first day of trekking was cause to establish our mateship. With trembling knees and a racing heart, I clung to DE to guide me to the flatter parts of terrain.

He ensured I was always within range of his watchful eye, providing words of encouragement and an ever-ready grip to guide my hand and small backpack.

Now, as we reach more manageable sections of the Trail, the relaxed pace prompts a good-natured humour; a welcome distraction for me from the harsh realities of the trek. It was on the second day of trekking that I asked DE about his life as a carrier.

He got the job in 2012 and is the only personal carrier on our trek. Unlike the other 34 carriers, DE is not shouldering tents, cooking equipment or the packaged-food supply we will consume over the 10 days.

He tells me ensuring my safety and well-being is his responsibility, and I also admire the way he moves about supporting his colleagues who, I observe, even while managing their backpacks, keep a close eye on trekkers, ready to offer help as required.

DE and I are following the Trail down to Diagiri Creek when, taking in the hazardous terrain around us, so absent of safety infrastructure, I ask him about the death of Winterford Tauno.

He delays his response, keeping his back to me and reverting to a habit of mimicking bird calls. I have empathy for his apprehension. A few minutes pass before he turns to answer my question but avoids mentioning Tauno.

DE describes an industry that is failing the men integral to the survival of trek tourism. He tells me that the poor regulation of Australian trek operators means that, unlike Adventure Kokoda, he has witnessed and heard of extreme cases of exploitation of carriers.

He suggests that when we reach camp at Ofi Creek, he will organise our trek guide and the carrier team to meet with me together.

That evening I hear the long list of issues reported by these 36 Papua New Guinean men who, as a result of dismal PNG-Australian management of Trail tourism, have benefited little as key contributors and stakeholders in the experience.

There are many matters requiring immediate attention by Trail management if Kokoda trek tourism is to emerge as an ethical, humane and well managed operation in Papua New Guinea.

Carriers Quarters

Boskuk moves about busily clearing the other end of a timber platform on which his assistant, Junior, and I recline.

He throws scraps of onion peel and ripped pasta packets into a garbage disposal bag as he makes his way towards us to inspect the evening’s dish washing efforts.

The various cauldrons that earlier held the trek group’s two-course dinner, have now been washed by Junior and a few carriers, their head torches guiding them at Lubu Creek nearby.

Visibly satisfied, boskuk moves back to the fire to remove the blackened tins, crushing them easily under his feet before placing them in a separate garbage bag.

With no waste disposal system implemented by the Trail’s PNG-Australian management, Adventure Kokoda adheres to strict company policy that rubbish produced by the group is taken when departing campsites and rest stops.

FOLLOWING the steep descent from Owers Corner, our first day of trekking brought us through the abandoned Uberi village, then across Goldie River before arrival at Imita base campsite.

Lagging behind with my guide and carrier, DE, I had not seen boskuk [head cook] or most of the carriers during those few hours. It was only when I sighted orange tents dotted across an expansive lawn and movement in the open-sided hauskuk [kitchen] did I understand the reason for their rapid pace over the day.

The group would move swiftly from campsite to campsite, where they would construct makeshift tables or lay out a tarpaulin on the leaf-layered jungle floor.

It was all well organised. Boskuk, Junior and the carriers ensured we trekkers could enjoy our refreshment breaks in a timely and hygienic way. Along the Trail, even the most basic facilities for the comfort of trekkers and carriers have been ignored by the Port Moresby-based management.

Over subsequent days, as my fellow trekkers and I heaped spoonful’s of energy-sustaining milo and sugar-laden instant coffee into individual mugs, I thought about the burden placed on Junior. Without the provision of elevated outdoor cooking facilities between villages, making and containing the small open fires fell to Adventure Kokoda.

A little matter, perhaps, but one of many deficiencies – large and small – which added up to a fundamental neglect of Papua New Guinea’s premier, money-making tourism lure oversighted by no less than five organisations: PNG’s Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA); Kokoda Track Authority (KTA); Tourism Promotion Authority (TPA); and the Australian-steered Kokoda Tours Operators Association (KTOA) and Kokoda Initiative (KI).

With all the funding available, mostly Australian taxpayers’ money, what consideration does this cumbersome management give to the well-being of Papua New Guinean carriers engaging in their hazardous work.

The Trail, although well-trod, is no walk in the park. It can endanger life and limb. Trekkers like me are privileged to have travel insurance. But what support is available to carriers should they sustain injury?

The conspicuous absence of safety measures such as hand-rails and barriers means that trekkers instinctively rely upon carriers for support as well as labour. They need breaks and rest-time just like those Trail managers back in Port Moresby.

My thoughts extend to the danger of open fires as an accelerant of environmental degradation. The Kokoda Trail is a vital component of the ecosystem of the Koiari and Orokaiva people.

Knowing how vigilant (to the extent of criminal sanctions) Australian society is about fires in forest areas, the seemingly lax approach to fire regulation of the Australian agencies that co-manage the Trail irritates me.

This pattern of management’s dismal commitment to environment sustainability and lack of interest in carrier welfare is no more evident than in the work and living conditions at campsites.

The flat terrain surrounded by short, sloping hills makes for a leisurely stroll down to Lubu Creek to bathe. Outdoor bathing is of course a routine challenge for trekkers but, given the popularity of the Trail, I am mystified by the absence of simple outdoor shower facilities.

With the exception of the Bombers and Isurava sites, each afternoon at respective camps our group shuffles across moss-coated boulders and warily traverses razor-edged rocks for a three-second rinse in ice-cold water – which at least has the benefit of jolting fatigued bodies back to exhausted life. The drudgery of changing clothes inside a two-person tent is equally unkind.

Half an hour after unsteadily negotiating a fallen tree trunk leading trekkers out of the creek, I emerge from my tent and head towards an impromptu tabol maket [table market] set up by local landowners. My trek mates proclaimed there were K8 cans of Coke and K3 packets of Twisties on sale.

At the tabol maket, I purchase three lukewarm soft drinks, taking one and leaving the others for DE and another carrier who had been gracious in lending his hand when DE’s two weren’t sufficient for my height-fearing brain.

I then saunter across the lawn passing the carriers’ sleeping quarters, a three-walled structure with an open front for all eyes to peer through. Scattered across the timber floor are rolls of red-cover encased zippered sleeping bags. Blue foam sleeping mats lie alongside bilums and discarded uniform shirts hang on the palm-thatched wall.

But the ghastly stench seeping from nearby camp toilets propels me straight back to the other side of camp, and into the haus kuk.

MOVING between the haus kuk and the neighbouring shelter structure, boskuk issues instructions to Junior before doing the same to a handful of nearby carriers.

I quiz Junior about the shelter’s tarpaulin roof and the company’s rope now strung into clothes lines across its length. I’m told this is the campsite owner’s offering of a drying haus. Adventure Kokoda supplies its own rope, purchases firewood from landowners and makes small fires to improvise a heating facility for trekkers to hand wash their damp clothes.

Boskuk reappears and rations out pasta spirals for the group’s evening meal. As Junior moves a water-filled cauldron off the platform, multiple one kilogram bags of rice come into view. I am told they are to be cooked for the carriers’ dinner. As boskuk moves forward, bending to empty the packets of pasta into the now-boiling water, I divert my eyes to the orange tents ahead of me to conceal my reaction.

I am embarrassed to be sitting idly whilst an older man moves about to prepare a meal for us and but most of all I feel irritated that Papua New Guinean men like boskuk are employed to create a tourism ‘experience’ struggling with primitive infrastructure.

As night falls, my irritation turns to anger the only source of light for boskuk and Junior as they move about with meal preparation, service and cleaning are our fire and their head torches.

Boskuk tells me he has worked in the industry for nearly 16 years and in all that time work conditions, have changed little. He points out that, with the first night’s meal eaten and breakfast tomorrow, the carriers’ pack weights will be lighter, but only slightly. I am bewildered that there is no en-route storage system at campsites for food, tents and other gear.

THAT evening, and in the days and nights thereafter, I continue to feel the same, distressing emotional outrage at the alphabet soup of KTA, CEPA, TPA, KI and KTOA which promote Kokoda as an icon but do so little for the men struggling on the Trail.

The lack of proper waste disposal systems, the absence of outdoor showers and fixed waist-level cooking facilities, poor drying houses, unsatisfactory toilet facilities, inadequate sleeping quarters for carriers and insufficient lighting….

All indicate a lack of communication, caring and action on the part of the management soup, which should be engaging with local campsite owners and trek companies to provide humane, safe and otherwise reasonable facilities for carriers, guides, trekkers and Trail communities.

THE issues I’ve described cause me to consider whether, in striving to achieve the ‘wartime experience’, Kokoda Trail management is either ignorant of, or unconcerned about, the shifting tectonic plates of modern-day standards and expectations.

If it is felt that Papua New Guinean carriers represent some kind of emulation of wartime Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’, this is a totally misconceived attitude.

It is one thing for trekkers to voluntarily embark on the challenges of Kokoda; quite another to expect that the workers who make this possible have to endure the poor conditions they do.

Not for them the return to a Port Moresby hotel and a comfortable life in Australia.

They’re back on the Trail.

Surely the PNG-Australian management of the Trail is not deliberately capitalising on the historical juxtaposition of troops and carriers, consciously limiting its investment in the welfare of carriers and advertently fostering poor practices in Kokoda Trail trek tourism?

Wartime Gratitude Morphs Into a Troubled Present

Taking turns, my fellow trekkers and I line up against the hand-built dining table chattering about the afternoon’s descent into this campsite at Ofi Creek as we wash our individual dishes and cutlery.

A pile of striped purple cleaning cloths are laid out for us to dry our implements before heading to our tents for the night.

I sit easily on the table’s bench seat, comfortably content after my meal of French onion soup, instant potato mash and tinned bully beef and hear DE’s gentle call from outside the hut’s thatched frame.

Kokoda – kukim kaikaiIt’s the signal that he and the other carriers, as well as the trek guide, boskuk and Junior, are ready for me to sit with them and talk. I gather my belongings, switch on my headtorch and walk towards the carriers’ sleeping quarters.

DE and I sit on the lawn near the entrance alongside a handful of carriers who have arrived late to the evening’s devotion. Inside, a text from Scripture is cited, moving on to a closing Seventh Day Adventist hymn. DE softly hums the melody whilst his colleagues with steady voice and pitch-perfect harmony sing along.

THE Ofi Creek campsite owner offers one of the better accommodation facilities for carriers on the Trail.

These quarters have four walls and a small doorway, the raised timber platform inside serving as a clean, warm and safe enclave to rest.

In here, the trek guide has cleared a spot for me. I take a panoramic view of the torch-lit room and see a few carriers already in their sleeping bags, dozing off for the night. But the majority are seated, exchanging brief, shy glances with me before looking away. It is the first opportunity since leaving Owers Corner that I will listen to the collective voices of these men.

The air rich with anticipation, I nervously turn to DE and ask him to open the evening’s discussion. Clearing his throat, DE embarks on facilitating a 90 minute discussion.

DE opens in Tok Pisin by explaining why I am trekking the Trail and shares his thoughts about our conversation after I had asked him about Winterford Tauno, a carrier who died on the Trail last September.

There are murmurs of agreement and I observe men whispering to each other. A brief silence ensues before the trek’s medic addresses the group in Motu. It is a language I am unable to understand but, glancing at DE, his relaxed facial expression reassures me that the medic is encouraging dialogue.

A senior carrier moves onto the earthen floor to address the group and begins to delve into a myriad of issues.

Most of them are problems seemingly fostered by the PNG-Australian Trail management’s weak regulation of trek operators and its lack of interest in advocating and enforcing the rights of carriers.

LET me be clear: without the Papua New Guinean carriers, there is no Kokoda Trail trek tourism industry.

Subsequently, there would be no need for the many people – bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, aid personnel – who rely on this industry for all or part of their livelihood. My guess is that most of them get paid more than carriers.

Our carriers tell me the industry daily rate is K60 but working for Adventure Kokoda they are paid K70 a day. It is just one of a long list of items where trek leader Charlie’s company differs from other predominantly Australian-owned trek operators.

The carriers take a break on a hilltop during the 10-day trek. They are part of a support team of 36.

For a 10-day trek, with all the hazards and hardships endured, carriers are paid K700. Upon reaching the Trail’s end, they are paid an allowance of K250 to walk-back to their village.

They tell me they are satisfied with their company issued uniforms of shirts, shorts and caps. All the carriers in this trek group wear enclosed shoes suitable for hazardous terrain. Rice, tinned meat and hard breakfast biscuits form the staples of their trek diet. When available, Adventure Kokoda purchases cooked garden food (corn, taro and the like) from communities for carriers’ meals.

They are issued with zippered sleeping bags and foam sleeping mats. They support the company’s strict policy to enforce across the industry an 18-kilogram pack weight limit. But they avoid discussing the death of Winterford Tauno.

Adventure Kokoda is also innovative in sourcing additional income for carriers. Trekkers are encouraged to pay a gratuity of K80 to them. At the Trail’s end, the gratuity from each trekker is pooled and distributed amongst carriers.

Trekkers are encouraged to purchase a Trail memento hand-carved by Adventure Kokoda carriers, ranging in price from K50 to K80.

In the end, a carrier completes a 10-day trek with between K981 and K1,081 in his pocket. That’s about $460 maximum. With added responsibilities and longer workdays, the trek guide, bos kuk, Junior, DE and the medic receive a slightly higher amount.

It’s not much of a reward in the context of the millions of kina generated by the trekking industry. In 2011, the most recent year for which I am able to find figures, the Trail generated $15.3 million in revenue.

I cannot help but ask the question, “Are the carriers upon whom this industry depends treated and rewarded fairly?”

Across the industry, carriers have two demands when it comes to remuneration: that the daily pay rate be increased to K100 or that they be paid an all-inclusive flat fee of K2,000 for the 10 day trek.

Furthermore, carriers have requested: assistance to access savings and loan facilities; and the establishment of a PNG Guide and Carriers Association, independent and free of any involvement by the current PNG-Australian managers.

A WEAK regulatory body means not all trek operators function in the same way as Adventure Kokoda.

Rampant inconsistencies were reported to me by carriers. The issuing of blankets instead of sleeping bags, day packs exceeding 18 kilograms, and inconsistencies in walk-back allowance (not K250 but K50–K100.

As we crossed Efogi Creek, DE and I encountered carriers working for another trek operator. Shouldering larger backpacks, the three young men wore slippers. It was one of many occasions that I witnessed inappropriate footwear.

Of all the concerns raised by carriers, the lack of medical insurance and life insurance causes them the most anxiety.

Having immersed myself in the wretched terrain and struggled with the lack of safe footbridges, I cannot accept what I believe to be the negligence by Trail management in ensuring such protections against harm. I wonder whether any measures were implemented following Winterford Tauno’s death.

The carriers’ uncertainty over workplace injury and death extends to their recruitment.

Carriers describe a robust trek tourism industry that takes on young Koiari and Orokaiva men who need to be employed. However, questionable practices by trek operators fuel a disturbing imbalance.

For example, not all Australian-based registered operators undertake tours year-round. Some operators undertake tours only at peak times (Anzac Day and school holidays). Unfortunately, such profit-driven choices have a devastating impact on employment for the Papua New Guineans who rely on the treks as a source of income. Unstable work means unstable income.

Carriers also report inconsistency in the selection process used by several trek operators. Adventure Kokoda’s carriers are recruited from every village along the Trail. This is advantageous not only for the carriers (and their dependants) but for the trek groups passing through communities.

However, some trek operators employ from just a single village while using all Trail villages for their passage on the land of the Koiari and Orokaiva people.

These issues cause much anger to be directed at Kokoda Initiative (KI) which the majority of carriers identify as having little impact. They say they are frustrated that, while carriers’ pay rates remain low, little attempt has been made by Australia’s DFAT-funded agency to deliver human resource development in which girls and women participate.

The carriers’ frustration extends to those Australian-steered, funded and based organisations that affix ‘Kokoda’ to their titles but do little to serve the needs of the marginalised Kokoda Trail communities. The carriers also express concern about the deteriorating ecosystem through littering, erosion and unnecessary felling of trees.

WALKING in silence back to my tent, I struggle to fathom the charm and stoicism carriers are forced to muster each day they are on the Trail.

Beside me, DE, with tired eyes, carries my washed plate and cutlery. His insistence on ensuring he accompany to return safely to my tent struck me as an embarrassing reflection on the managing body of his industry.

The carriers of the Kokoda Trail, seemingly forgotten by those in Port Moresby and Canberra, are relentless in their duty of care to trekkers.

The spirit of their World War II forefathers still resides in them, but the gratitude of those weary troops they served does not seem to have survived the journey to the present.

Dispossession – No Joy for Women in Kokoda Tourism

A baby blue shawl thrown across an elderly woman’s bony frame complements the deep orange sweet jelly produce positioned beside her. She lowers her eyes as the trek group edges past her towards the forest border.

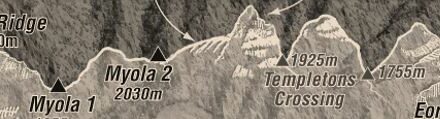

Standing a few metres away, trek leader Charlie Lynn rehashes his presentation as I tap my fingers across the keypad of my phone. I note details of mortar relics resting in an open, rusting cage in the forest bordering Myola 1 village.

An absence of information boards on the Trail means Charlie’s thorough knowledge of World War II’s Kokoda campaign is crucial. Today is the sixth day I’ve been learning about the military history behind our long 10-day pilgrimage.

This day we are privileged to have the campsite owner of our previous night’s stay at Bomber’s as our tour guide. To acknowledge his time and knowledge, donations from the group are collected by Charlie and presented to him.

Trek tourism not only seems unable to benefit from signage, the villages along the Trail are not benefiting much either. Providing fixed shelters would encourage interaction with and sales to passing trekkers.

The elderly woman I’d seen had resorted to assembling her impromptu market on a fallen log. My trek mates walked past showing little interest and otherwise absorbed I, too, did not make a purchase.

Not until walking onto the prairie-like landscape of Myola 2 village did I remember, with a pang of regret, the lone woman in the forest hoping for a kina or two.

ON the eighth day a mid-morning venture off the Trail down to Maeaka Falls has my trekking pace slow to a daydreaming stroll.

The roar of the majestic waterfall is softened by the tranquillity of sunlight filtering through the tree canopy. Light sprays of water land on my face.

There’s no signage to educate trekkers of the site’s wartime significance, so we rely on Charlie’s account of the devastating ambush and the deaths of Lt Col Ward and troops of his 53rd Battalion.

A sombre mood cloaks our group’s short climb back to the main Trail where we reunite with our backpacks and the rest of the carriers.

Back on the Trail heading toward Abuari village, I enjoy a relatively easier climb and manage to appreciate more of the natural splendour of my surrounds where lilac flowers are scattered among the wild shrubs.

My trance is interrupted when ahead of me by loud laughter and a playful exchange between my carrier DE and the medic. The two young men trigger a recurring thought – How are the women and girls of the Trail communities benefiting from trek tourism? I think of the old woman on the log.

Opposite me, four women of various ages stood at intervals along the table. I enquired about the price of three pineapples: “K15, K12 and K20.”

I’m conflicted about how to efficiently spend K40 so as to share snacks with the carriers and offer a token of my thanks to the group of Menari villagers whom DE has organised to speak with me.

Eventually, I buy some packaged food, bananas and a few cans of drink, making an effort to purchase from each of the four women. Only one or two other trekkers purchase drinks and bananas from the women whilst we await boskuk and Junior who busily prepare the group’s lunch in the midday heat.

I move to one end of the table where bilums [string bags] are on sale. They depict nothing unique, being the rather generic styles sold in Port Moresby.

Then, remembering an earlier conversation with one of the female trekkers, I ask the women about the sale of sanitary products. Stone wall. Eye contact lost. Worried at their discomfort, I ask if there are small trade stores nearby where I may purchase them. I am told a curt “no”.

Only later as I sit with a few female trekkers, a young woman from the maket approaches to inform me that sanitary products are sold but only from individual homes. She offers to go to one and make a purchase, for which my fellow trekker is grateful.

Days later, back in Port Moresby, I am concerned when I hear about a proposed Kokoda Initative-funded program aiming to encourage economic participation by women in Trail villages producing and selling re-usable sanitary products.

The proposed model, trialled in another region of PNG and now to be replicated, is that they be sold in market places. Afterwards, citing the incident at Menari, I let it be known through other channels that the public sale of these products on the Trail is likely to be culturally unacceptable and meet with resistance from the women.

UPON arrival in Abuari, DE directs me straight to the haus kuk to talk with Junior.

Dodging a low beam, I enter the haus kuk. Junior is nowhere to be seen. Hunched over a simmering cauldron, boskuk points to a covered dish on the narrow platform. Lifting its lid, I see a mound of boiled corn and taro.

In my eight days on the Trail, it’s the first time I’ve been offered or even seen the organic produce, a staple in the diet of remote Papua New Guinean communities.

As part of the trek tourism experience, I had expected to regularly consume local cuisine. It was a disappointment for me and fellow trekkers that, during the 10 days between Owers Corner and Kokoda, we had not seen a mumu. Trail communities were again missing an opportunity to earn some money.

Adventure Kokoda’s established rapport and direct investment in the women and girls of Abuari village means today’s lunch consists of two meals: the hearty, fire-cooked meal prepared by boskuk and Junior plus an assortment of baked treats prepared by the women’s group.

In the cool of an elevated hauswin [gazebo], sugar donuts, slabs of butter cake and fresh bread rolls are laid out alongside platters of passionfruit and bananas. There are also trays of fried kaukau, a favourite amongst the Australian trekkers. At the end of the meal, a payment of K15 from each trekker is collected by the guide and given to the women.

Away from the lunch table, the women offer cold cans of soft drink and packaged chips for sale, which members of my trek group purchase enthusiastically.

Later, speaking to a representative of the women’s group, she describes how Adventure Kokoda’s provision of drum ovens and essential baking supplies has fostered a system where meals are prepared for the company’s trek groups. The company has also donated hand-operated sewing machines that are used to make goods for sale by this community and the people of nearby villages.

Unfortunately, this was the only time on the Trail I observed women engaged in sustainable development activity; one example only of active participation in and direct benefit from trek tourism.

The morning fog has still not lifted when we descend into Isurava village to stop for morning tea.

I sit on a log next to trek mate, exchanging comments of delight about the neatly-kept rose garden beside us.

As we much on packaged cream biscuits, Junior moves about preparing the beverages. The air is still cool and we look forward wrapping our hands around warm mugs of milo, coffee and tea.

Just metres away, two middle-aged women sit. Near them, small children amuse themselves. In front of them stainless steel and floral design tin dishes have been placed on a clean white sheet. The usual cans of Coke, bundles of Twisties and ripe bananas fill the dishes. By the time our group is ready to move on, no one has moved towards the women and their small market.

WITH this final observation of a pattern of failed enterprise, I am overcome with inconsolable grief in front of Charlie and DE.

I struggle to articulate my despair at seeing the unrewarded effort and dashed expectations of women and girls seeking to benefit from the tourism through their land.

Just as I turn away from Charlie and DE to head off and collect my backpack, a senior carrier hurries towards me with a small bunch of bananas.

Handing them to me, he says the women, still seated with their unsold wares, have asked him to bring the fruit to me as a gift.

Inadequate Infrastructure Mars the Kokoda Trail

Extending his arm back toward me, low-slung and with fingers splayed, DE warns of a winding navigation of Emoo Creek.

At a standstill facing me, hand elevated and shoulders curled towards his chest, DE’s eye movements map out a path to safely manoeuvre the slime-coated incline of Nauro Lookout.

With short, clear instructions received from over my shoulder, he gently insists on my full concentration when clambering amongst floating logs in swamps and he steadies my balance through light pressure on the small backpack on my shoulders.

Here on the Kokoda Trail, the PNG-Australia management of the trek tourism industry seem to have put little thought into personal safety measures for trekkers, carriers and guides.

Along the 138 kilometres between Owers Corner and the Kokoda plateau, the absence of handrails, steps and secure footbridges raises many questions about the investment in safety.

In places, our lightweight trekking poles enable unsteady pivots and lunges. Crossing streams, the carriers line alongside impromptu handrails constructed with red rope, their bodies protecting us from razor-sharp rocks protruding from the white water gushing beneath felled logs.

DE and I co-exist in a relationship where my hesitant glances are reciprocated with empathy and a quiet dignity as he gently negotiates my journey throughout the ten days.

Images in the history textbook of ‘fuzzy wuzzy angels’ aiding Australian soldiers anchor the role DE and his colleagues continue to this day.

And yet, unlike the World War II military campaign, the modern-day enterprise of wartime tourism earns money; generated in most part by the labour provided by Papua New Guinean men.

Moving along the ever-changing corridor floor of the Trail, I muster humility to entrust my welfare in DE’s professional judgment in this difficult environment. I admire his stoicism despite the hazards – but, at regular intervals during gruelling uphill climbs, I am visited by pangs of worry.

This is a clear dry-season day in August and it is easy to overlook DE’s offering of a helping hand along a well-trodden incline where no handrails are to be found.

But what about the wet season months of April onwards when the popularity of Anzac Day motivates pilgrims and Australian school students to flock in droves to the Trail? Does the laissez faire approach of PNG-Australia management continue, or are safety measures improved for carriers during this peak period for trekking?

I LEAN IN to shake hands with the elderly man and exchange morning pleasantries before stepping back to stand just behind DE’s shoulder. As DE continues conversation with his uncle, I scan the surrounding landscape. My mind working like a camera, I take shots of Efogi village.

To my right, red hibiscus shrubs border a pathway of short grass leading to a small health centre, Nearby are the community health worker’s house and a school.

Earlier that morning, trek leader Charlie, the trek Guide, DE and another carrier with me in attendance had ventured along this path to deliver Adventure Kokoda’s medical supplies donation to Efogi’s health centre.

Despite it being the Sabbath, the community health worker with three small children in tow kindly offered to show me her workplace. I moved across the timber-slat verandah and linoleum-covered floors and through the treatment rooms, freshly painted, clean and organised, the health worker very considerate in responding to all my questions.

I was particularly interested in maternal care, and was shown the maternity room. It was clean and tidy but my heart sank when I saw the out-dated delivery beds: unsuitable and extremely uncomfortable.

I felt sorry for the mothers whom had given birth on these beds, which reminded me of one on which I endured the traumatic delivery of my daughter at Lae’s Angau hospital in 2010.

The health worker told me that, most often at the seventh month of pregnancy, women walk to Efogi to stay with relatives. After delivery, they and their babies return to their villages to which the community health worker regularly patrols to administer immunisation and medical checks.

As I stepped outside, a flash of fluorescent pink and yellow appeared in my peripheral vision. On the wall was a neat, hand-drawn chart detailing the clinic’s daily schedules including sessions allocated for women to access family planning, antenatal and well-baby clinics.

Also along the same grass path were a drying house structure and a new-looking generator. Both were idle. When I asked passers-by, I was told that they were part of an Australian aid project and of little use to the community.

The generator looked large enough to run a compound of homes, if not the health centre I had just visited. Lacking the ability to purchase and transport fuel, the generator remains dormant except for special church celebrations or the arrival of important people on chartered flights.

To my left, across a football-sized field of slate-coloured soil, was a row of traditionally thatched timber homes raised on wooden stilts. At this distance, I am unable to make out any movement. The villagers were part way through their allocated time of holy worship.

I turned the other way to where an expanse of a stone and hardened-clay wall guarded one end of Efogi and stood in stark contrast to the lush, manicured lawn leading visitors to the village centre.

With dusk approaching I began the quiet walk to our campsite ten minutes past the main Efogi village tucked away in a back corner. Except for the soft glow from the small fires in the haus kuk and carriers’ quarters, we were in pitch darkness.

The carriers switched off their head torches off when transiting through villages on their Sabbath, echoing trek leader Charlie’s reminder to maintain respect. Walking sightless and in silence, I clung to DE’s arm and followed his heels through slight dips and a scattering of loose gravel as we made our way to the camp.

I picked away the dirt clinging to my trousers as we exchanged stories of how exhausting the day’s hike had been. But relief overshadowed this when I considered how I had bathed on the previous previous night.

Arriving at Efogi campsite after nightfall, I was again confronted with the sole option of bathing by the riverside. Fearful of what might have been in Kavai Creek and for my personal safety, my anger flared again at Trail management neglect of the investment to provide even minimal facilities and to work with the campsite owners to ensure the well-being and safety of trekkers and trek staff.

Two carriers on their way back to the camp stopped and offered to assist. With caution, I stepped into the ice-cold water, scanning for water snakes, leeches and other threats. It wasn’t until I heard DE’s familiar voice that I dared to partially immerse myself in the water.

ADVENTURE Kokoda has a long-established relationship with the owner and his family at Bombers campsite.

Through the company’s investment and support, the campsite offers foam mattresses and pillows for the overnighting trekker. The hot sower facility is an initiative of the owner; designed through experiment and skilful use of the nearby river.

As with the women’s group at Abuari village, the trek company had pledged the donation of a drum oven to encourage the inclusion of women as participants and direct beneficiaries of the Trail’s informal economy.

Pit latrines are the current standard and they are consistently unsafe, unclean and unhygienic, meaning that the trend is for trekkers to ‘go bush’ rather than put up with the foul stench and unsteady infrastructure of the pit.

So what does insufficient investment in the Trail’s infrastructure mean? Well it’s all tangible – added pressure on carriers to act as shield-guards in the absence safety handrails; the felling of trees because there are no fixed and secure footbridges; the practice of bathing directly in the rivers; going bush for toileting… and the rest.

It is of great concern that the ecosystems and livelihood of the Koiari and Orokaiva people continue to be degraded and exploited as a consequence of insufficient investment, weak regulation and a questionable sustainable development approach to the Trail’s wartime tourism industry.

Deep commemoration & missing interpretation

COLLAPSING on top of the clay-baked ground, my trek group seeks refuge from the midday heat under the cool of an awning.

A stream of loose dust swirls past, dancing toward the row of aged banana trees bordering the edge of Menari village. I reach for the nozzle of my hydration bladder and take three appreciative sips.

Beside me, trek mates use the interval to rummage through their backpacks and Band-aid strips, jellybeans and small bottles of sunscreen are offered around – along with tips about redistributing weight in the packs.

I’ve been accompanying trekkers nominated by New South Wales RSL clubs who are participating in their annual Kokoda Youth Leadership Challenge in partnership with Adventure Kokoda.

Fourteen of the group are employees of RSL branches and two are soldiers serving with the Australian Army. Like trek leader Charlie and the trek guide, their daily khakis are enviably immaculate despite the daily grind of uphill climbs and unsteady clambering through swamps.

It is a multicultural group reflective of contemporary Australia and it is the first visit to Papua New Guinea for all 16 participants.

Our group has sought shelter under the eaves of a private home and, as we await Charlie’s arrival, my gaze drifts across the clay floor, freshly marked with broom strokes. Nearby split firewood is assembled in perfectly symmetrical pyramids.

Since departing Owers Corner, I have observed no effort has been made by landowners to distinguish or restrict personal property from that for public access. No signs, no barriers but an unheralded and hospitable blurring of boundaries.

My fellow trekkers and I chatter – still building rapport and navigating boundaries – while the constants in this tourism experience remain invisible: the villagers, home owner and occupants, listening in silence out of eyeshot.

As stillness is to movement, the communities of Kokoda Trail live in a parallel reality. To facilitate the multimillion-kina income generating industry, an inward-facing PNG-Australia management has found no certain means for the traditional landowners of this historic route, replete with battle sites, to extract their due benefits from wartime tourism.

There’s another gap. By the time I reach the Kokoda plateau, I will have observed management’s dismal efforts of commemoration and interpretation of the World War II Kokoda Campaign.

Along the entire Trail, the investment required to offer this flagship of PNG’s tourism industry is missing. Miserably so. My observation is echoed by an exasperated Australian trek mate who, early in the trek, remarks: “For all we know, we could be on an everyday hike in PNG.”

What is more evident is that the Papua New Guinea government has been complicit in not commemorating the PNG men who sacrificed their lives, especially, the wartime carriers. And more than this, there has been an exclusion of their descendants from interpreting the military history to foreigners who walked through their front and backyards.

As we sit in one of their houses, encroaching upon their personal living space, they squat under the floorboards, perhaps eavesdropping on our conversations.

___________

“YOU HAVE seen things in this place that no man should witness, some of things you must forget, but none of will forget our fallen comrades. Your efforts have ensured they have not died in vain. History will remember you, and in the years to come others will wish that they had your conviction and determination…”

These historic words bring to a close trek leader Charlie’s talk as we sit heads bowed and with sagging shoulders in our sweat-stained shirts. They were the words of Lt Col Ralph Honner to a tired and diminished 39th Battalion given in this same location 76 years ago.

Charlie’s perfect recital is met with the prolonged silence of youth who in this place are now realising the magnitude of sacrifice made by their forefathers. Delivered with sparing glances at his mobile phone, Charlie imparts to us also his own momentous dedication.

It is difficult to not consider the reaction of Honner’s descendants who have stood in this village with no sign to mark its history. I only hope they felt a tribute more heartfelt than the shade of a private dwelling.

Moving on to address the program objective of preparing trekkers for leadership roles within the Australian community, Charlie builds on Honner’s encouragement of “man’s exultation” being made in “faithfulness and fortitude, gentleness and compassion”. These are words with universal meaning.

I survey the faces of my trek mates.

Stoic expressions and tear-streaked cheeks; eyes giving Charlie full attention. I notice a woman with bloodshot eyes settling her gaze on the village square. I fix my own eyes in the same direction, not wanting to invade her privacy but to also find a distant corner to offer my eternal gratitude. This is a sacred place.

I reflect on the appreciation I have developed for my trek mates who have demonstrated a genuine interest to learn about Papua New Guinea, its history and present-day issues. I admire the friendliness, respect and rapport they have built with our team of carriers, our guide and the community members we have met along the way.

These long hours on the Trail sharing words of encouragement and exhibiting patience, compassion, kindness, resilience and humour have highlighted the leadership potential of each one of my 16 trek mates.

MENARI is near halfway along the 138-kilometre trek: a benchmark for us and the thousands of people who have been here before us; an achievement which signals there is still much to achieve.

In retracing the footsteps of the men who fought and died for the freedom of others, our first wartime briefing takes place at the sheer cliff face of Imita Ridge Gap. As Charlie explains that this was the final obstacle for the Japanese Army in its advance toward Port Moresby, we look upon the eye-straining letters of a dirt encased plaque cemented at ground level.

It’s a fixture exemplifying the pattern of commemoration and interpretation we encounter along the Trail. Tributes that are sporadic, weathered and seemingly half-hearted.

As we walk across the open fields of Lake Myola then descend alongside the cool of Eora Creek, I am deeply saddened by the lack of tributes and the failure to relate to the pilgrims the profound significance of these sites.

An uphill climbs takes us past vine-covered ammunition pits that would remain inconspicuous if not for Adventure Kokoda’s carriers motioning us to their position. Attempts to preserve mortar relics are apparent in the forest as we move towards Tovovo Ridge.

I inspect the neglected remnants of the wreckage of a US Army P40 Kittyhawk fighter plane. There is nothing to mark its story but shards of painted metal scattered and embedded in a floor covering of decomposing leaves, snapped twigs and unruly weeds.

And more oversight and neglect again when, just before the descent to Templeton’s Crossing, Charlie indicates a large rain tree that is the only reminder of the site of the Boili Mail Exchange Point, where mailbags from Port Moresby and Popondetta were exchanged between mail carriers.

The 72 pickets remembering the heroes of Brigade Hill

The physical existence of the Kokoda Trail assures us of its place in world military history. Yet the lack of opportunities for learning, the lack of memorials and of places designed for quiet contemplation mean that the wartime tourism experience falls disturbingly short.

The recorded history of the Kokoda Campaign in the pages of textbooks, in libraries, on the internet and in the curated displays of museums has failed to be translated on the ground.

SEVENTY-TWO pickets stand in rectangular formation towards the back of the lawn. Pinned to the top of each is an artificial red poppy.

Some metres away, a weathered plaque sits near the edge of a steep cliff. At ground-level, a sign outlines briefly the events that took place there between 5 and 9 September 1942.

Sitting in a curved row, we trekkers form a low wall along the eastern face of the ridge. Wedged between trek mates and carriers, elbows resting on my bent knees, I cradle my face in my hands.

Charlie is midway through recital of NX 6925 Sapper Bert Beros’s poem, ‘A Soldier’s Farewell To His Son’: “I hope that you will never know, the dangers of the sea / And that is why I leave you now / To hold your liberty.”

The words echo around me as cold slices of air. They hover in the blurring focus as I stare at the short blades of grass at my feet. I’m unable to meet the gaze of those around me.

Charlie moves to a reading of ‘WX Unknown’. I offer a silent word of eternal thanks to each of the 72 Australian heroes each signified by a mere wooden picket inserted into PNG’s mountain soil. Through the eyes of a mother, this seems too slight a tribute of remembrance for such an irreplaceable loss.

—

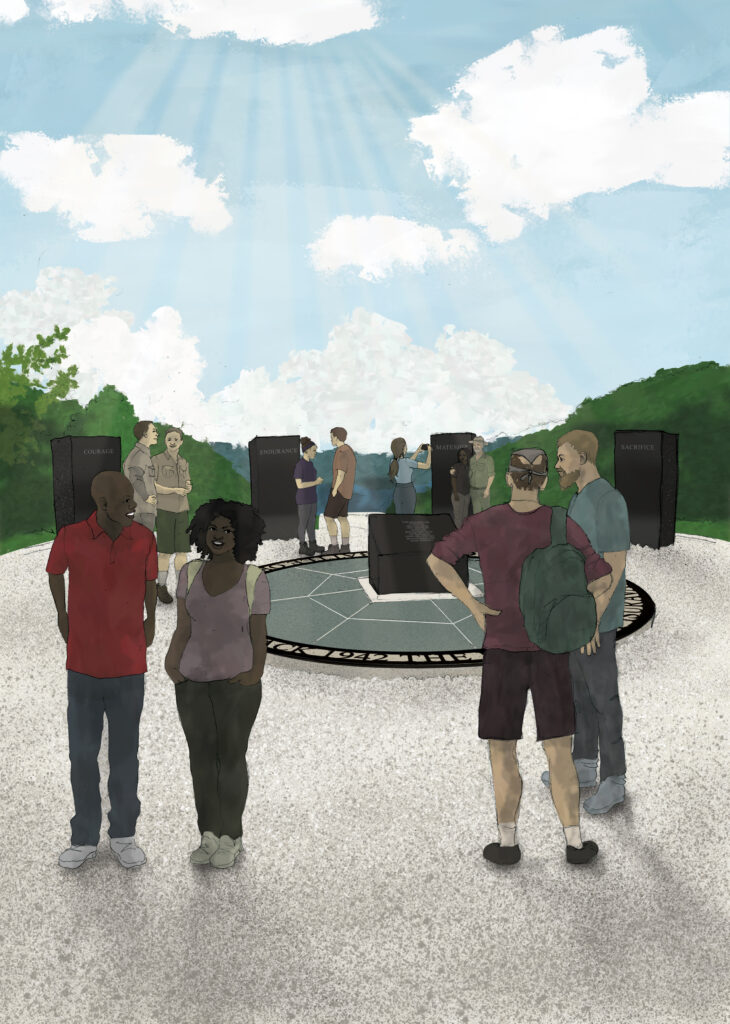

A SEA of light from head torches guides me to the steps of the monument, its grandeur concealed in the pre-dawn darkness.

Whispers of ‘good morning’ float from trek mates already seated. Copies of Adventure Kokoda’s ‘Isurava Memorial Pre-Dawn Service’ are passed around. I scan the program and turn my head torch off before standing to full attention.

Against four granite pillars, three short lines are formed by our trek guide, Bos Kuk, Junior, trek medic and the carriers in their full uniform of red, black and gold. I sight DE in the back row, throw him a wave and his face breaks into its familiar shy grin. Trek leader Charlie signals the beginning of the commemoration.

On the staircase, I stand with Australian trekkers. On the other side of the monument DE and the modern-day Papua New Guinean carriers face us. Our trek group has temporarily divided so we can take turns paying respects by singing our respective national anthems.

My life of privilege is illuminated and I add my breaking voice to the soulful harmony of my countrymen a few metres opposite. Then in unison I add it to the singing of my trekker peers standing beside me, whose homeland has also been mine.

The Papua New Guinean guides, carriers and other trek staff have their photograph taken after the dawn service at Isurava

As the service draws to a close on my second-last morning on the Trail, those four granite pillars bearing the words Endurance, Courage, Mateship, Sacrifice stand tall in the background as the Papua New Guinean men, who are so deserving of respect and recognition, take turns shaking hands and exchanging warm words with the line of Australians.

On that morning, one day short of completing our ten days together, I know this feat was made possible by the leadership, selflessness and bravery of the generation who went before us 76 ago and in whose name we made our pilgrimage along the Kokoda Trail.

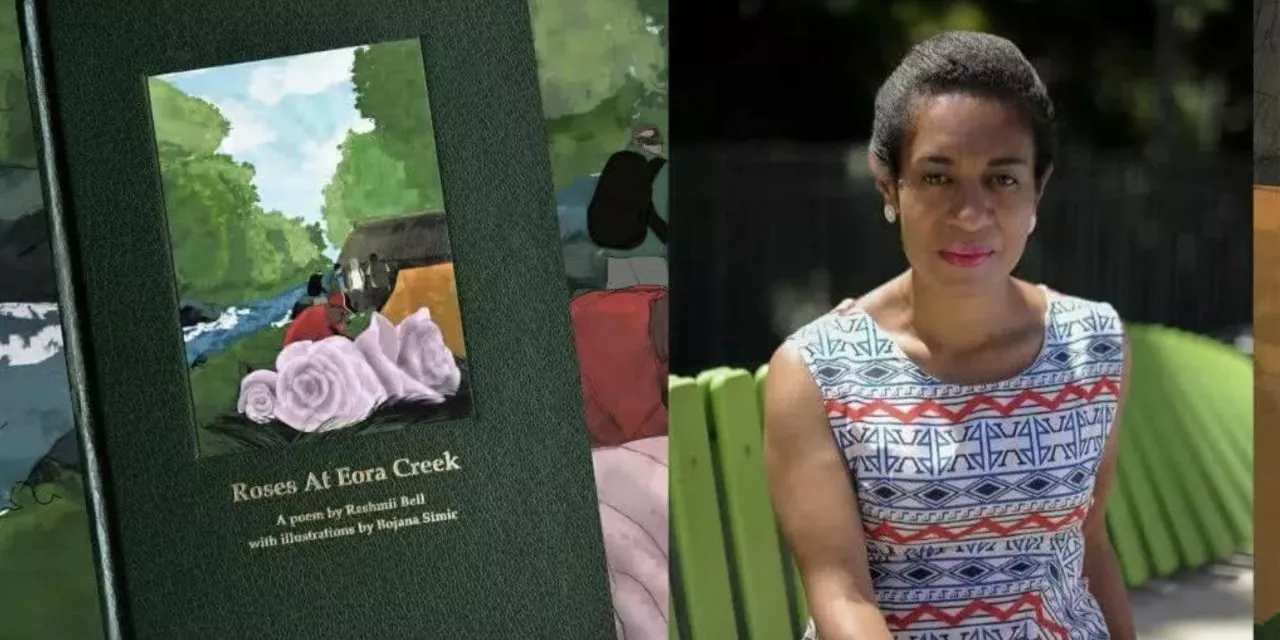

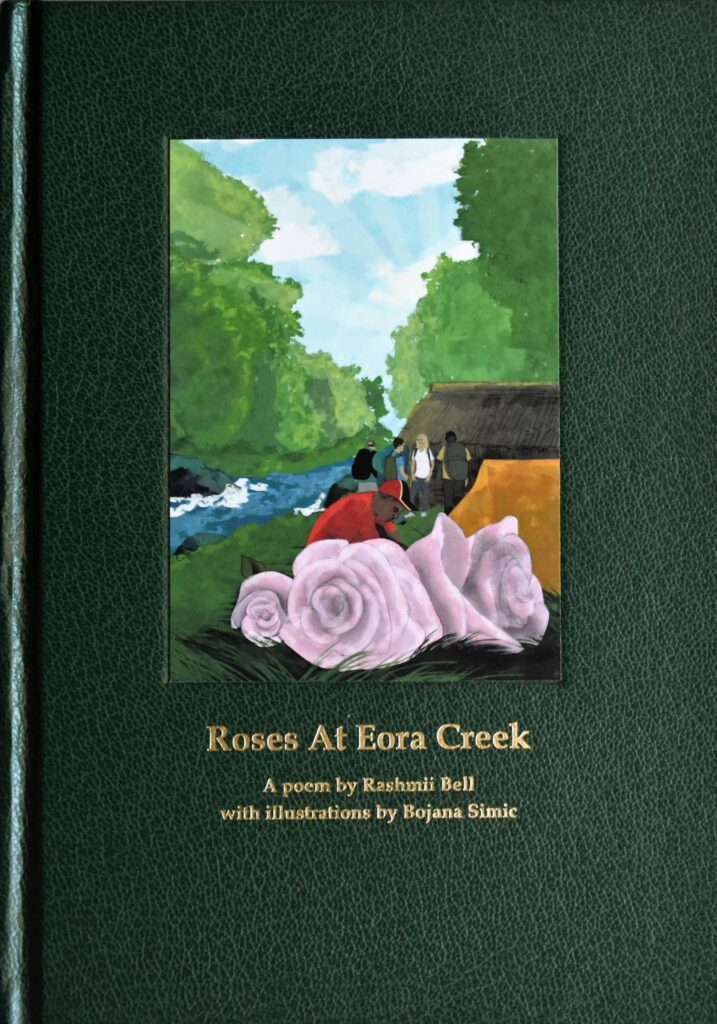

ROSES AT EORA CREEK

A beautiful piece of prose by Rashmii Bell about the evolving relationship between a trekker and her personal porter

OWERS CORNER TO IMITA BASE CAMP

Rashmii

It’s a clear August Day as I stand at Owers Corner,

contemplating the 138 kilometres that lie ahead.

A dark green mountain range unfolds before me. A monument is just steps away.

I look across to the faces of my trek mates, mostly Australians, some starting to

rummage through their packs,

as I set out to find my carrier, a Papua New Guinean.

As it was during the Kokoda Campaign 1942, a local man will walk the track by my

side.

He’ll carry my backpack daily, limited to 18 kilos, as it was in wartime, so that I can

reap the benefits of my pilgrimage.

I’m told his name is Ovoru.

Ovoru

For six years I have walked the Kokoda Trail,

doing what the brave Papua New Guinean men of the wartime did.

Guides, carriers of supplies and the injured.

Just like they were to each other,

a friend to the courageous Australian soldiers.

Today, I walk beside their cousins, nephews, nieces, grandchildren,

and the tourists who journey to retrace precious steps.

For the next ten days, I’ll walk.

Shouldering each day, I’ll take more if carriers ask, and as trekkers need my help.

I sit near near the hauswin arranging my pack as my dark grey hiking boots appear

alongside the red and yellow stripes of my uniform. She reaches across the table to

shake my hand. A shy introduction.

“Hi, I’m Rachel”.

It’s a fast and steep descent once your feet pass the arches. David is acutely aware

of the trembling running up from Rachel’s knees, and takes her arm to steady her,

encouraging her with each slow step.

IMITA BASE CAMP – OFI CREEK

Rashmii

4am is Reveille, the bugle, its distinctive cry.

Trekkers murmur, move, wake.

I hear Bos Kuk and his assistant Junior preparing our hot breakfast.

Slow, careful movements. Arched backs hover awkwardly, straining over large steel

cauldrons, on top of an open fireplace.

I think about my usual home comforts, taken for granted.

A wide bench to prepare food, a barbeque stand to cook, an outdoor sink for

washing hands and plates, safe and comfortable for all to use.

Here, safety and comfort is replaced by risk and making do, to fill the hungry

bellies of trekkers.

Ovoru

Rolling up my foam mat and zippered sleeping bag, I step onto the lawn dotted with

orange tents.

Flickering headlight torches inside canvass walls guide my path to number 155.

Her bag lies beside the flyscreen door, the tent ready for me to pack.

I’ll refill her two drink bottles from nearby Lubu Creek.

Rachel might slip on the sharp, moss-covered creek rocks hidden by early darkness.

Knowingly, in appreciation, she’s left coffee sachets for me

OFI CREEK TO AGULOGO

Rashmii

Sturdy and taught, red rope is the makeshift handrail.

Carriers lead Australians across fast-flowing Brown River.

There is no permanent bridge in sight, only fallen tree trunks and a rocky pathway.

As David announces our turn to cross, I follow his lead.

So many important decisions he is asked to make, to keep us safe each day.

OVORU

More confident with balance now, Rachel inches across the floating logs. Curious,

apprehensive, alert to the overgrowth of Nauro swamp.

Both hands free, I reach out to guide another trekker,

fatigued by her pack and the uneven, downhill climb.

She sips quickly from her hydration pack. I suggest we stop.

I add her sleeping bag and sandals to my daily load.

The shriek of young men’s laughter pierces the campsite, weaving through the forest

of ancient trees. At the carriers’ sleeping quarters, weary, quiet chatter blankets the

cool night sky.

AGULOGO TO EFOGI (Via Menari and Brigade Hill)

Ovoru

Brigade Hill a site significant, affecting.

Rachel is quiet, our easy banter and laughter on hold.

My historical recount of battles I delay for now. Talk about our dreams for the future

on hold.

Her trek mates also sombre, as history makes itself felt.

The listening trek group learns about the personal sacrifices made by young

Australian soldiers.

As I walk some steps behind, my thoughts move ahead to the downhill climb,

sparse handrails and loose rocks for the steep descent.

We, the carriers of trek-tourism, memorise every footstep of this trail.

Wartime it is no longer, but the Spirit of Kokoda must live on.

Rashmii

My heart, a weight of sadness as the words of A Soldier’s Farewell to His Son linger.

72 pickets stood, modest, a single red poppy on each,

as our trek leader guides us in remembrance with utmost respect.

Now at corner’s turn,

grey, jagged, the stone cliff stands guard to Efogi below.

I reach for David’s hand, knowing it would be outstretched toward me.

Aware, grateful, my carrier’s willing act is my barrier from danger.

It’s dusk when we walk out onto the flat grassland.

EFOGI TO BOMBERS CAMP

(Via Laununumu, Kagi and Tovovo Ridge)

Rashmii

A kettle whistles. Coffee, Milo, tea and cream biscuits.

A blue tarpaulin, a red tablecloth, on a patch of the green forest floor.

Sauntering past Laununumu, Kagi and along Tovovo Ridge,

I arrive to Bos Kuk and Junior’s welcoming buffet.

Cold air rushes past the tin mug warming my face.

As it nears my lips, aroma, contents sweet, energised by the empathy of our cooks.

Now braced for the short hike to Bombers.

Ovoru

Early arrival to camp, orange tents glisten in the afternoon sun.

The pack I leave beside 155.

A foam mattress, hot shower, soup and pasta.

The trekkers will sleep well tonight.

I stay awhile, listening to the young Australian men, their stories and questions for

me, kind.

A game of rugby is suggested. My cousins and neighbours would like my new

friends.

Fast, cheering, we play,

The night’s dark settles fast, as bitter cold cloaks Moss Forest. Not a sound heard

from the quarters’ four solid walls. The carriers, warm and resting in zippered

sleeping bags.

BOMBERS CAMP TO LAKE MYOLA 1 AND 2

Ovoru

Bombers’ campsite owner walks with us today, with local knowledge, present and

past.

The Australians listen intently, their eyes graze the wide spanning plain

where their forefathers waited for airplanes bearing food rations.

Lake Myola is also our history, we, Papua New Guineans.

We are the custodians of this land.

We continue to embrace our closest neighbours, now as tourists on pilgrimage, 76

years on.

Inclusion, benefits, fair and proper award deserved,

for hard physical labour provided, information shared, preservation and our future.

BOMBERS CAMP TO EORA CREEK

Rashmii

Australian soldiers, young men,

wounded, maimed, dying, once laid out on canvas stretchers in this cool, dark corner.

In commemoration, but a small plaque stands.

Listening to the Trek Leader’s recount of defensive battles,

I look back upon the steep incline, ragged, unkind.

My descent only possible with David, ever close by.

Tears fill my eyes, imagining the urgency for a sense of mateship,

stumbling, crawling, fully aware of the danger that once threatened the banks of

Eora.

ROSES AT EORA CREEK (EORA CREEK CAMPSITE)

Ovoru

Tear streaked faces and lowered eyes, Rachel walks ahead in a line of shoulders, sunken, around the creek bend, out of view. Lingering behind, I shoulder cauldrons and sleeping mats for other carriers, gone ahead to assemble tents, floral garlands and the evening meal. As I approach, white wash crashing, my name echoes from the make shift bridge, two logs across the raging stream. Pointing up to towering boulders, the carrier motions to two bursts of pastel wedged between dark grey. I’m told she stood awhile, admiring their beauty, in this hallowed place. A smile, wide but brief, now nestled alongside history, of all whom have come before.

Expressing words of thanks, the trekkers are delighted by purple bougainvillea

decorating their tents. Passing tent 155 and its neighbours, David pauses briefly

and kneels, placing a pink rose beside each flyscreen door

EORA CREEK TO ISURAVA MEMORIAL (Via ALOLA)

Rashmii

Courage. Endurance. Mateship. Sacrifice.

Four pillars that must be remembered, always.

At dawn, I stand at Isurava Memorial,

alongside Australians and Papua New Guineans,

offering our respect, and words of eternal gratitude,

for the bravery of young men, who forged a special bond between the people of two

nations.

We, carriers and trekkers, have come to acknowledge, appreciate and cherish.

HOI TO KOKODA PLATEAU – KOKODA AIRSTRIP

Ovoru

Bos Kuk before departure, shared jokes and instructions

in varied tones, hushed.

Long before Reveille, he leaves Hoi to share his cooking skills with others,

training young women to prepare breakfast, to sell to the inbound trekking tourists.

Hours later, I will walk the same path, Rachel by my side,

laughing, recounting, reminiscing.

As we approach those arches, both of us joyous,

our steps captured to memory and in photo,

Rachel, another pilgrim of Kokoda, forever my friend in life.

Rashmii

Sliced pawpaw, omelette and scones, freshly baked, straight out of drum-ovens.

Steam swirls up to meet the white screen of morning fog,

dissolving off the ledge of Kokoda Plateau.

Between mouthfuls of delicious breakfast, side embraces and arms around

shoulders,

warm exchanges between trekkers and carriers,

there is gifting, sharing of items, traditional and from lands afar.

Stepping forward when called, each carrier is presented with wage and gratuity,

a token of heartfelt appreciation.

Those who have trekked Kokoda understand.

Later, I weave through the group in search of that familiar voice,

final moments with David, my carrier, forever my friend in life.

Aboard the small aircraft, awaiting the take-off from Kokoda airstrip, Rachel peers

out the window. As he did at Owers Corner, David sits rearranging a trekker’s

backpack. Laughter and chatter circulate between the Papua New Guinean men and

Australians, pilgrims and carriers, side by side.

We will remember them.

Lukim Yu – Lest We Forget

COMMENTS:

Posted by: Peter Sandery | 10 September 2018 at 10:55 AM

Apropos of the generic comments about aid here-in contained and the many comments on it in various other discussions on this site, I recommend Tadagh Purtill’s, “The Dystopia in the Desert – the silent culture of Australia’s remotest Aboriginal communities”. Which is specific to the eastern section of the Western desert region of Western Australia, but applicable in my humble opinion to all aid. I have seen but one critique so far of the book and that from reporter Nicholas Rothwell who has gained a reputation for writing on matters Aboriginal generally, and art in particular. An indication to my cynical mind that Purtill may well be on the right track with his theory which therefore should play a part in any economic/risk analysis in all pre-aid discussions.

Posted by: Rashmii Bell | 24 September 2018 at 07:12 AM

Thanks, Peter.

Perhaps generic, however if you access Twitter and view my account @amoahfive_oh – there you can view images that I have posted ( and will continue to do so) that are very specific to my concerns. I have added commentary that asks specific questions if the agencies involved in the management of of the Trail.

Thank you for the title recommendation. May I also recommend a reading of Professor Paige West’s ‘ Diposession and the Environment: Rhetoric and Inequality in Papua New Guinea’. It is context/ PNG specific.

Posted by: Paul Oates | 09 September 2018 at 12:10 PM

Rashmii has effectively identified the real problem. There are just too many aims and too many cooks in the kitchen.

Are people being encouraged to see where the battles took place? Yep! That works elsewhere in the world. Just look at Gallipoli and the Western Front battlefields.

Are enthusiasts being attracted by outdoor physical challenges? Yep! That works in places like the European Alps and Kathmandu.

Is eco-tourism on show? Most certainly but what and where is it promoted and the experiences highlighted?

Are the cultural experiences and interaction with local people and their culture effectively managed? The jury may still be out on that one.

If the whole concept of the original promotion of the Kokoda Track were to be disentangled from what it has now obviously become, could anyone really say what the simple aims are and are they being met?

The RSL may well have a totally different set of objectives to those who are clearly trying to make a bob or two out of the concept and out of a PNG experience.