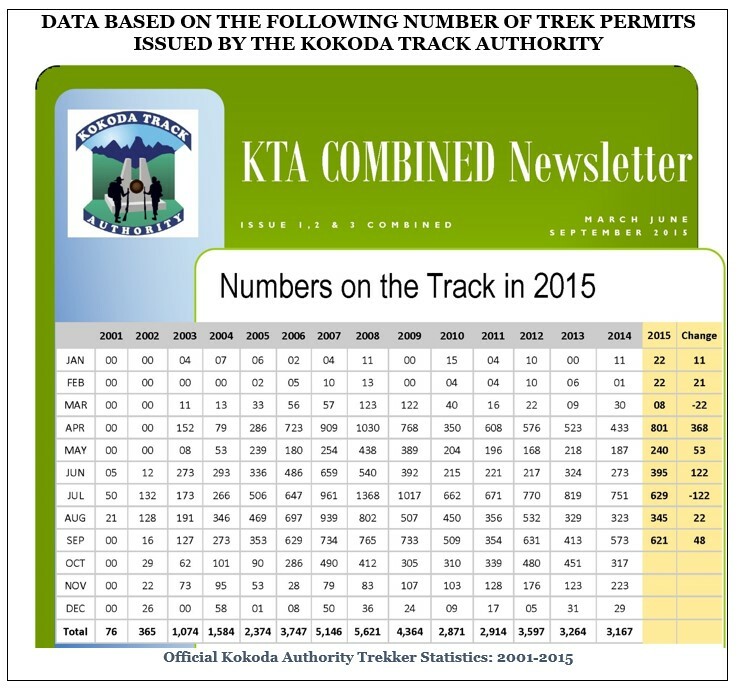

Official data, based on the number of Trek Permits issued by the Kokoda Track (Special Purpose) Authority (KTA), reveals that villagers across the Kokoda Trail have suffered a cumulative loss of K49.7 million in foregone income opportunities since the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative assumed responsibility for its management in 2009. A Kokoda Livelihoods Study by Pacific Islands Projects revealed the DFAT-Kokoda Initiative allocates just 1% of their budget to ‘income generating projects’ for villagers across the Trail.

KEY FACTS

- Prior to the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 1992 fewer than 100 Australians trekked across the Kokoda Trail each year. They did not have to pay any fees and were self-sufficient with their own camping gear and ration packs.

- Apart from employing one or two local guides, and buying some fresh food, there were few economic benefits for local subsistence villagers. Their only opportunity for earning some income was through the sale of fresh fruit and vegetables which were delivered to Port Moresby by MBA Airlines via a thrice weekly ‘milk-run’ along the Trail.

- In 1992 the combined annual income for all villagers across the Trail was estimated to be in the region of $30,000 (PNGK60,000) per year.

- Public interest in trekking Kokoda began with a cover story in the ‘Bulletin with Newsweek’ magazine titled ‘Kokoda: A Walk on the Wild Side’ which coincided with Prime Minister Paul Keating’s Anzac Day visit in 1992.

- A later national television special, ‘The Angry Anderson Kokoda Challenge’, featuring a group of celebrities was screened in 1996. It was the highest ever rating show for the ‘A Current Affair’ and attracted almost 3 million viewers.

- On the 60th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2002, Prime Minister’s John Howard and Sir Michael Somare opened a significant memorial at the Isurava battlesite.

- The publicity from these events led to an increasing interest in trekking across the Trail.

- At the same time, local villagers began to agitate for a more reasonable share of benefits from the emerging Kokoda trekking industry.

- In 2003, the Kokoda Track (Special Purpose) Authority (KTA) was proclaimed by the Minister for Intergovernmental Relations, Sir Peter Barter, to help meet their needs.

- A former kiap, and long-term PNG resident, Warren Bartlett, was appointed CEO of the KTA on a salary of $12,500 (PNGK25,000). He was assisted by a part-time secretary. The organisation was required to be self-funding as neither government, Australia nor PNG, were willing to provide any financial support at the time.

- Mr Bartlett requested financial assistance from Adventure Kokoda who advanced $10,000 to the fledgling organisation until income from the introduction of trek permit fees began to flow.

- Under the new Kokoda Track Permit Law, 20% of income from Trek Permits was to be allocated for administration purposes and 80% allocated for community development projects across the Trail.

During this period Mr Bartlett processed 19,546 trek permits, maintained the VHF radio system across the trail, issued toilet pans, generators, mowers, etc to village communities, administered the only ever all-inclusive workshops conducted on the Kokoda Trail, and did his best to meet the demands of 80 trek operators, more than 100 landowners, and corrupt elements within his own KTA Board of Directors.

The challenges he had to deal with during this period included:

Landowner communities came to expect that all trek fee income was to be used for community projects. With no financial assistance from the Australian/PNG Governments for recurrent expenditure, a proportion of trek fee income was required for recurrent expenses. It was not possible to engage suitably qualified administrative staff. All the work was therefore left for Mr Bartlett.

Mr Bartlett was required to attend to the routine activities of KTA – process Trek Permit applications, account for all funds, attend to community and tour operator/trekker enquiries, and attend to all accounting matters. It was almost impossible for him to manage the required developments to support the needs of local communities and the trekking industry.

Kokoda Trail communities were aggrieved that they were not properly represented on the board of the KTA. They came to believe that they were not receiving their fair share of trek fee income for community projects and that the board was squandering money on unnecessary management expenses. Their complaints were fully justified but could not be addressed because of the Board structure and the apathy of the Australian/PNG Governments at the time.

The Koiari and Kokoda Local Level Government appointees on the management committee were too involved in daily administration and political intrigue with the expenses that supported their activities. It was not possible to control their pillage of trek fees and they lost the respect of the people they were supposed to represent. For example, they demanded the KTA fund all their meeting allowances, accommodation, and transport expenses for meetings in respect of KTA matters even though they were paid by their respective Provincial Governments.

KTA budgets could not be approved without the support of the Local Level Government members. With any eye to their own political futures, they demanded community benefits be distributed to all the wards in their Local Level Government Areas – many were well beyond the geographic confines of the Kokoda Trail.

Central and Oro Provincial Administrations failed to provide any budgetary support to the KTA. They reversed their onus of responsibility to support the fledgling trekking industry and pressured the KTA to fund some of their expenses.

KTA funds in excess of K1 million were misappropriated due to political and peer pressures by wan-tok leaders and management committee members.

Landowners lodged many false claims with the KTA for track clearing, bridge replacement, medical (welfare) expenses, education, aircraft and road transport, vehicle hire, community meetings, etc. It was impossible for the KTA to assess or supervise these claims however many had to be paid to prevent disputes leading to trek closures.

Koiari and Orokaiva villagers living in Port Moresby settlements continually lodged claims without reference to their village communities.

Significant portions of tree canopy were destroyed as campsites were established without reference to the KTA.

It was not possible to fund any ‘awareness patrols’ or village workshops across the Trail due to funding restrictions. This led to a great deal of discontent within local communities along the trail.

Many of these issues were due to government apath; an institutional neglect to ensure Board members were properly aware of their responsibilities; and a failure to institute proper checks and balances. Despite these shortcomings the experience provided valuable lessons in developing proper procedures and structures to harness the potential of a World class wartime trekking industry.

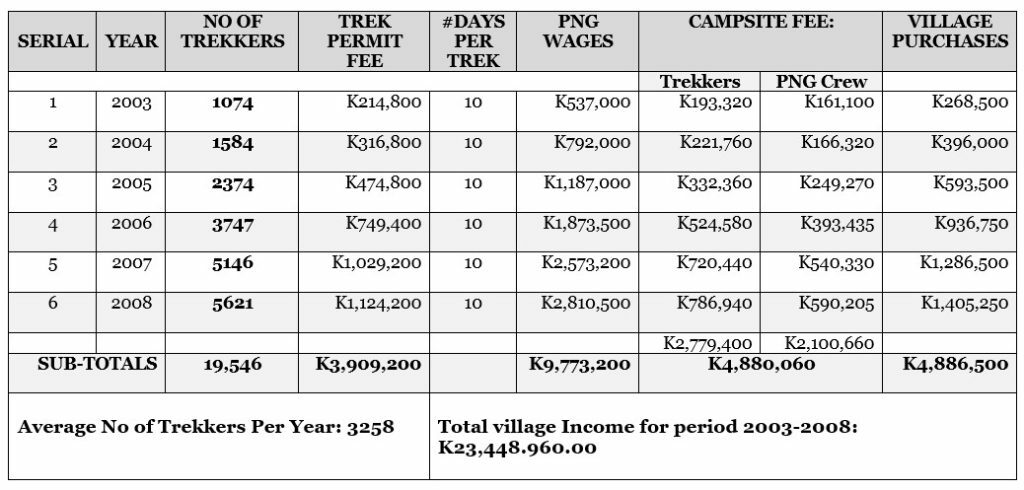

During Mr Bartlett’s reign as CEO from 2003 to 2008 the KTA raised $2 million from the issue of Trek Permits; $5 million was earned by guides and carriers supporting trekkers; $2.4 million was earned by campsite owners; and a further $2.4 million was earned by villagers from the sale of food, souvenirs and local sing-sings for trek groups. See Table 1 below.

Australian Management Results: 2009-2019

A public backlash against a threat to mine the southern section of the Kokoda Trail caused the Australian Government to assist PNG to obtain a World Heritage Listing for the area.

A Joint Agreement, signed in 2008, saw the Australian Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) assume responsibility for the management of the emerging Kokoda trekking industry the following year. An Australian CEO was appointed on a salary package of approximately $300,000, and staff numbers increased from one part-time assistant to 15 full-time employees (10 office workers and 5 rangers).

A DFAT ‘Kokoda Initiative’ was established and embedded within the PNG Conservation Environmental Protection Agency (CEPA) which assumed responsibility for the KTA through the establishment of a Ministerial Technical Working Group. An Australian environmental official was embedded within CEPA as their ‘Strategic Management Advisor’.

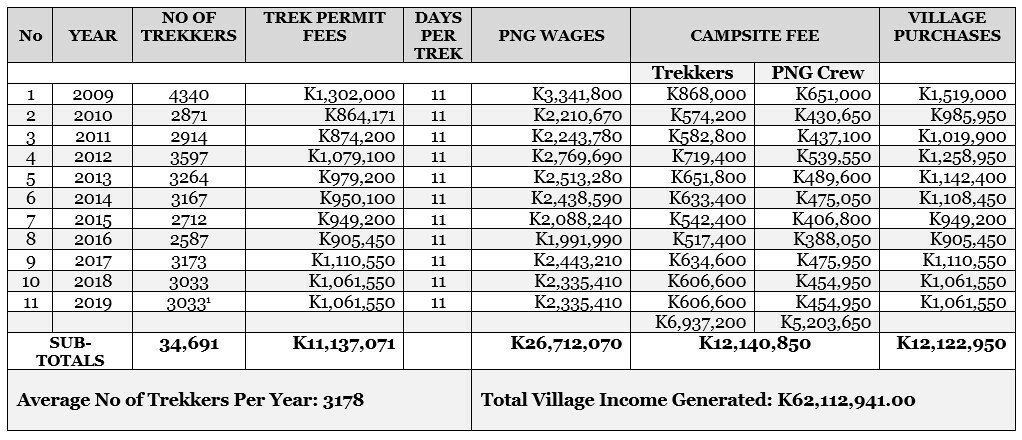

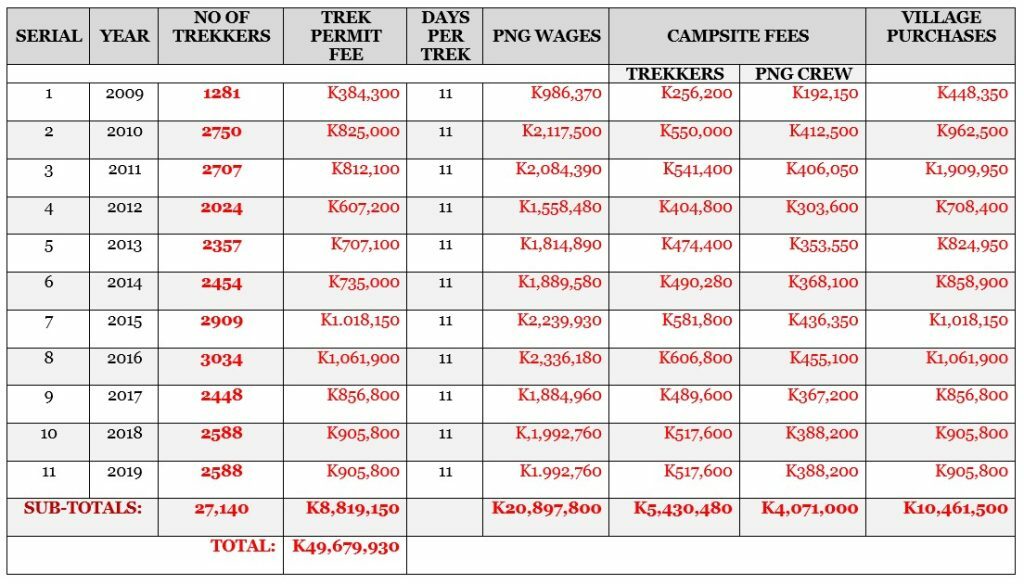

The period 2009-2019 saw a decline of 27,140 trekkers which resulted in a cumulative loss of $20 million (PNGK49 million) in foregone income for villagers across the Kokoda Trail under the management model imposed by the DFAT ‘Kokoda Initiative-CEPA-KTA Alliance’.

The annual decline can be measured against the 2008 benchmark of 5621 trekkers under PNG management in 2008 as per Table 3 below.

Summary

During the period 2003-2008 the KTA, under PNG Management, generated a 423% increase in trekker numbers from 1074 to 5621.

During the period 2009-2019 the KTA, under Australian management, there was a 46% decline in trekker numbers from 5621 in 2008 to 3033 in 2019.

The decline, measured against the 2008 benchmark of 5621 trekkers has resulted in a cumulative loss of $20 million (PNGK49 million) for villager communities across the Kokoda Trail.

These villagers, who earned zero income from trekking over a 40-year period from 1950-1990, have earned $28 million (PNGK68 million) over the past 16 years from the emerging Kokoda Tourism industry. The total benefit related to Kokoda tourism (international air fares, hotel accommodation, charter aircraft, ground transport, camping gear, food, medical supplies, etc is in the region of $250 million (PNGK600 million) during this period.

Conclusion

The decline in trekker numbers from an average of 3258 per year under PNG KTA management to 3178 under Australian management resulted in a cumulative loss of $20 million (PNGK49 million). This is due to the fact that the Trail has being managed as an environmental asset by government bureaucrats rather than as a commercial tourism asset on a free-enterprise basis.

This is evident in the fact that the DFAT Kokoda Initiative-CEPA-KTA Alliance has not introduced a single management protocol since 2009.

It is therefore not possible to book campsites in advance. There is no trek itinerary management system which leads to confusion and conflict during peak trekking periods. There is no trek auditing system to ensure guides, carriers, personal porters and campsite owners are not exploited. There is no due diligence in the KTA licensing system which has led to a proliferation of trekking companies who do not comply with the IPA Act or their own KTA regulations. No funds have been invested in the development of campsites – there is not a single toilet that meets the most basic of hygiene standards across the Trail. They have not yet developed a database which is the most fundamental management tool of any commercial enterprise. They have not invested in the military heritage of any significant site which is the primary reason Australians choose to trek across the Trail. They have never produced an annual financial report.

An expert report in 2015 revealed that the Kokoda Trail does not meet the criteria necessary for a World Heritage Listing. There is therefore no justification for continuing to manage the Kokoda Trail as an environmental resource.

The rapid growth in trekker numbers has seen the Trail emerge as PNGs most popular tourism destination. It should therefore be managed as a tourism resource on a commercial basis for the economic and social benefit of village communities between Owers Corner and Kokoda.

The following data supports this conclusion:

- Table 1: Data for Period 2003-2008 (Under PNG Management)

- Table 2: Data for Period 2009-2019 (Under Australian Management)

- Table 3: Data re loss in each category with the decline in trekker number since 2009 against the 2008 PNG KTA benchmark of 5621 trekkers

Table 1: Data for Period 2003-2008 (Under PNG Management)

Calculations for income generated within village economies are based on the following:

- Trek Permit Fee of PNGK200.00 per trekker;

- Daily rate of pay of PNGK50 per guide and carrier

- Average of 10 days employment during each trek (1-day preparation; 8 days trekking; 1-day post-trek admin

- K20 campsite fee per trekker for an average of 9 nights per trek;

- K5 campsite fee per guide/carrier/personal porter for an average of 9 nights per trek; and

- An average spend of PNGK250 per trekker for village purchases (fresh fruit, local sing-sings, bilum bags, etc)

Table 2: Data for Period 2009-2019 (Under Australian Management)

Calculations for income generated within village economies are based on the following:

- Trek Permit Fee of PNGK300.00 per trekker increasing to K350 per trekker from 2015;

- Daily rate of pay of PNGK70 per guide and carrier;

- Average of 11 days employment during each trek (1-day preparation; 9 days trekking; 1-day post-trek admin;

- K20 campsite fee per trekker for an average of 10 nights per trek;

- K5 campsite fee per guide/carrier/personal porter for an average of 10 nights per trek; and

- An average spend of PNGK350 per trekker for village purchases (fresh fruit, local sing-sings, bilum bags, etc

Table 3: Data re economic loss for villagers in each category with the decline in trekker numbers against the 2008 benchmark of 5621 trekkers

[1] Permits and Finance Officer instructed not to provide trek numbers – 2019 figure based on estimate from 2018