The story of Kokoda is second only to Gallipoli in the annals of Australia’s military history – but it’s been a slow awakening!

Since Prime Minister John Howard and PNGs Grand Chief, Sir Michael Somare, opened a solemn memorial at Isurava on the 60th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign in 2002, scores of books have been published, television documentaries produced, and more than 54,000 Australians from all walks of life have trekked across it.

It was inevitable that the pilgrimage, which is a serious physical and emotional challenge, would eventually attract its share of rent-seekers from the government aid-sector, urgers, and dodgy trekking companies.

The creation of a false narrative by former army officer, Captain Brian Freeman, saw Channel 7 presenter, Mike Munro and General Sir Peter Cosgrove inadvertently roped into a publicity scam relating to the ‘discovery’ of a ‘lost battlefield’ on Ko’koda.

Freeman, who had previously assisted Executive Excellence ‘with Sales and Marketing’ and was ‘a trek leader on selected Sandakan and Kokoda adventures’ applied his marketing skills to the publishing of a book on his discovery which enhanced his reputation considerably and saw him engaged on the lucrative speaking circuit where he was billed as ‘arguably Australia’s greatest ever Adventurer and, certainly, one of a handful of the world’s current outstanding Adventurers.’

Since his departure from Executive Excellence in 2007 Freeman has started up – and wound up – several Kokoda trekking companies including Centori (deregistered in 2018), Norgay Freeman (deregistered in 2021) Freeman High Performance (deregistered in 2021), Adventure 35 (deregistered in 2022), and Adventure 1000 (deregistered in 2022). He is now associated with Adventure Excellence by reputation, but not by name.

Freeman has also claimed to have achieved some superhuman physical feats which include a kayak paddle from the tip of Cape York to Papua New Guinea combined with a trek across the Kokoda Trail – all within 6-days! His claims would obviously be more credible if he was to provide some official verification on his ‘Brian Freeman Blog‘.

Some rather ordinary reviews on his book proved to be no impediment to his rise and rise on the corporate speaking circuit due to his aggressive ‘sales and marketing’ skills:

Nikki wrote:

The parts about the lost battlefield were interesting, unfortunately you have to wade through a blow-by-blow account of the author’s military service (and name dropping) first.

Joy Norman:

Enjoyed most of the book would’ve liked to read more about ” the lost battlefields” I felt this was a really important part of the story however it got glossed over where at times more emphasis was placed on individual characters.

David Vernon:

An interesting tale which gives a brief history of Brian Freeman’s life before exploring the issues around the lost battlefield. Ghost written by Tony Park (his name should appear a little more obviously in the book and the acknowledgements) the style is easy to read and compelling. Rather not enough information about the actual battlefield and too much about Brian’s business dealings. Nonetheless an interesting book and a good expose of the difficulties of working in PNG and also with getting bureaucracies interested in history.

An ABC documentary on Freeman’s neglect to account for more than $1 million in a ‘Walking Wounded’ charity he established resulted in General Sir Peter Cosgrave, and Dr Brendan Nelson (CEO of the Australian War Memorial) disassociating themselves from him. The tax-free charitable status of ‘Walking Wounded’ was revoked and the company was later deregistered.

However, by this stage the publicity surrounding his ‘discovery‘ of a ‘lost battlefield’ led to the establishment of a ‘Lost Battlefield Trust’ and generated a throng of aid-seeking officials, archaeologists, anthropologists, and hobby historians in search of relevance. They ignored suggestions that it could have been a contrived publicity stunt by Freeman.

Of more concern is that DFAT officials in the Australian High Commission seemed to ignore their responsibility to report the discovery to the army Unrecovered War Casualties (UWC) unit in Canberra as there was no evidence of their involvement in the documentary, they funded for the PNG National Museum. UWC maintains a highly skilled forensic team to investigate any reported instances surrounding the discovery of our war dead.

Instead, they devoted their resources to investigate a Japanese position at the rear of the Eora Creek battlefield. This is difficult to understand given there are Australian soldiers who are still listed as MIA in the areas of Deniki, Isurava, Abuari, Eora Creek, Templeton’s Crossing, Mission Ridge and Brigade Hill but there has been no attempt to explore these positions by the DFAT Kokoda Initiative or the Australian High Commission in Port Moresby.

Freeman certainly knew which buttons to push by publicly claiming the site could contain the remains of an Australian soldier – ‘The watch was an Australian watch, the buttons were off an Australian uniform, and the boots he was wearing were Australian boots’ he claimed on a promotional video for the television story. This claim was later found to be false as it was identified as a Japanese soldier whose remains were repatriated to Japan.

As a former army officer, Freeman should have been aware that from a military perspective, the selection of ground for a defensive position includes the identification of ‘ground of tactical importance’. This refers to that part of a defensive position that makes the rest of the position untenable if captured by the enemy.

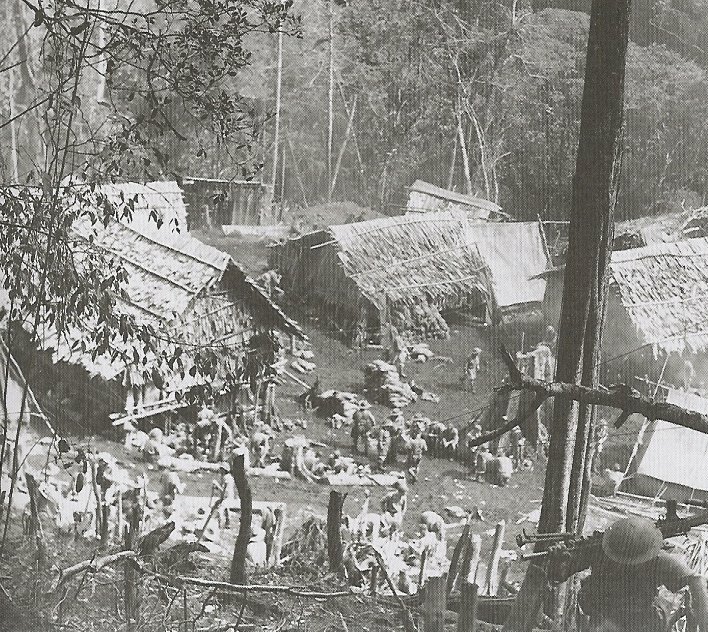

At Eora Creek the ‘ground of tactical importance’ would have included the existing trail and the northern feature which dominates the creek overlooking the wartime (now abandoned) village pad of Eora which trekkers have been visiting, and sometimes camping at, for more than 50 years.

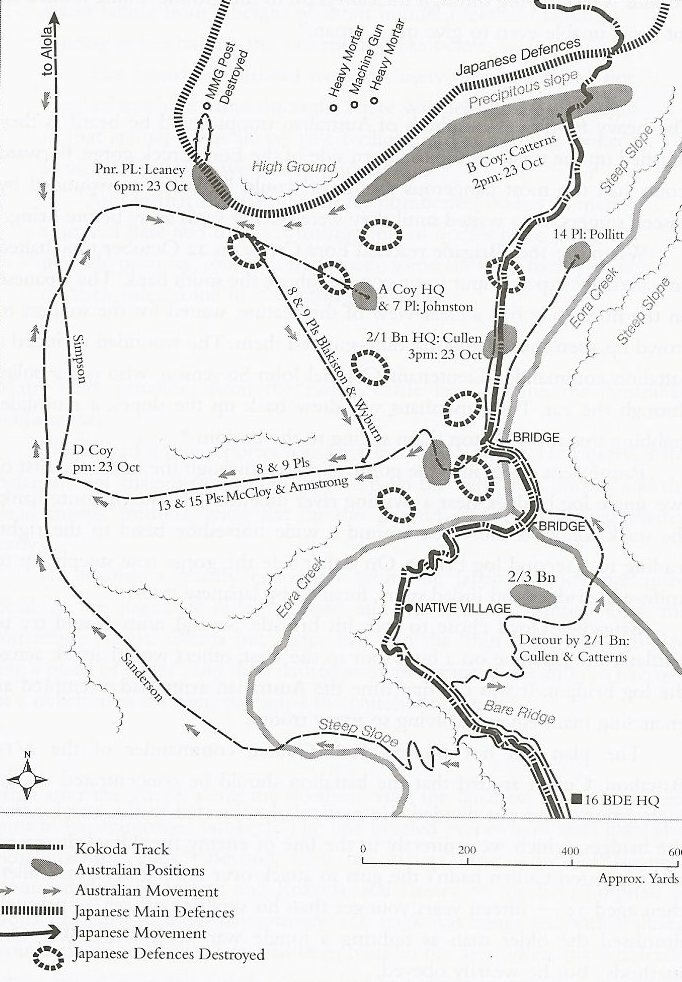

The Australian 16th Brigade was allocated the task of attacking the Japanese defensive position at Eora Creek. The battle was fought during the period 22 – 28 October 1942. The 2/1st and 2/2nd Battalions attacked on the main axis of the track and the 2/3rd Battalion probed the right flank of the Japanese position and then attacked from the west, forcing the enemy to withdraw from the ‘ground of tactical importance ‘.

The western flank of the Japanese position is not visited by trekkers because trek itineraries do not allow for it. The same applies to Mission Ridge, Ioribaiwa Ridge and the north-western sector of the Isurava defensive position. None of these battlesites have ever been claimed to have been ‘lost’ – they are all well known to those who specialise in the wartime history of the Kokoda campaign which includes authoritative military historians such as Lieutenant Colonel Rowan Tracey, Frank Taylor, Gary Traynor, Nick Anderson from the Army History Unit, and Susan Ramage, author of ‘Kokoda Secret’.

The area Freeman claimed to be a ‘lost battlefield‘ is most likely a Japanese medical aid post which was located immediately to the rear of the main Japanese defensive position to treat their wounded.

This did not deter the throng of aid-seekers from cashing in on the discovery!

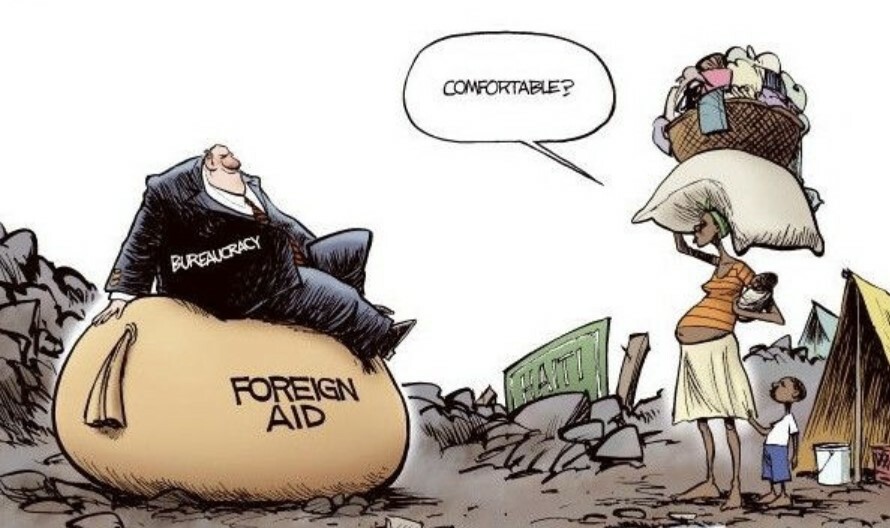

Dr Andrew Moutu, CEO of the PNG National Museum and Art Gallery (a gift to the new Papua New Government at Independence) has a good antenna for the flow of aid-dollars and quickly joined the throng. His museum had recently benefited from a $25 million refurbishment by the Australian Government as part of the ‘build-decay-rebuild‘ cycle of aid funded structures in PNG.

Moutu also knew which buttons to push to tap into DFATs desire to ensure the PNG indigenous stories associated with the war are told!

He gave it an indigenous name ‘Etoa‘ that nobody had ever heard of. Whilst DFATs desire to tell the PNG story is a noble cause it is 70 years too late for the Papuan veterans and wartime carriers, who were ignored for all those years, to provide personal accounts of their experiences as they have passed on. The fact that ‘Etoa‘ does not appear in any previous cultural or military history publications was not a concern as they preferred the fictional account of the battle and pressed on with their desire to promote it.

In the meantime, trek leaders who had followed the trail through the Eora Creek battlesite for more than 30 years were aware that the weapons displayed by Mike Munro in the Channel 7 story had been on display in a hut at Alola village for almost a decade before Brian Freemen first trekked it. The owner of the hut charged $5 to view them. It appears they were conveniently relocated to Freeman’s ‘Lost Battlefield’ to provide a degree of authenticity to his ‘discovery’.

Two Kokoda historians have weighed in on the debate after reading of the ABCs intention to screen ‘the fallacy of the lost Kokoda battlefield’.

Gary Traynor, a former Assistant Curator at the Australian War Memorial and an experienced tour leader for military history expeditions to Kokoda, Gallipoli, Western Front & Thai Burma Railway, has led treks across Kokoda for many years and is also the originator of ‘Medals Gone Missing’ where he devotes countless hours in recovering lost medals for veterans’ families.

Traynor recently posted a response to the ABC rehash of the DFAT-funded propaganda film on Dr Moutu’s fictional ‘Etoa’ which was first screened to a local audience in PNG in early 2020.

‘I recall when the documentary was first aired so many years ago, that Brian Freeman and Peter Cosgrove were filmed with two rusty, relic machine guns. The story was insinuating that these two weapons were found on the “Lost Battlefield”.

‘I immediately recognised both relic guns as having been removed from the privately owned museum at Alola Village. One of the guns was a Bren, but the other was a stand out …… it was a Type 92 machinegun, which was a Japanese copy under licence of the British Lewis gun usually mounted in aircraft (often seen on British WW1 fighters as the Lewis mounted on the top wing that was on a rail and pulled down from the top wing for reloading). This particular Japanese Type 92 had been recovered by the original owner of the museum, from the Japanese G4M bomber wreck on the high ridge between Isurava Battlefield and modern Isurava. So, a minor misrepresentation of the truth.’

Lieutenant-Colonel Rowan Tracey, a Sword of Honour recipient from the Royal Military College, served with the PNG Defence Force during his army career and is fluent in ‘Tok Pisin’. He has been trekking Kokoda for 35 years and discussed the campaign from a PNG perspective with many of the village elders who have since passed on.

He has also discussed the campaign with Kokoda veterans who have also passed on and has an extensive library of published papers and books on the campaign. He has been invited to address international conferences at the Royal United Services Institute and the Australian War Memorial.

According to the late Major-General Gordon Maitland, Tracey is Australia’s leading exponent of the history of the Kokoda campaign because of his understanding of ‘ground‘ from a military perspective.

According to Lieutenant Colonel Tracey :

‘The extent of the battlefield at Eora Creek which the Japanese defended in their withdrawal to the northern coast of Papua in 1942 is well recorded and not “forgotten”.

Many books portray the fighting there in detail, including an authoritative description in a publication by the Australian Army History Unit. Therefore, it is hard to understand why the battle is characterized in this way and described under a new name by the ABC. There are many other military sites on the Kokoda Trail which are more demanding of investigation than Eora Creek and receive no attention.’

In 1992 Kokoda historian, Frank Taylor, installed a plaque with the following inscription, at Eora Creek on the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign:

The Japanese made the whole area a major defensive position during their retreat. The tired Japanese resisted determined frontal attacks by fresh Australian troops from 22 October for over a week. Australians advancing on the west bank of Eora Creek overcame the enemy eventually and when almost encircled, the Japanese hastily abandoned their positions retreating to Oivi and Goiari. Eora Creek village once the centre of much of the heavy fighting now lies abandoned. The crashing, haunting noise of the fast-flowing creek below brings vividly to mind the turmoil of battle, and the men who fought here so long ago.’

The ABC airing of the fiction of ‘Etoa’ has now given an underserved degree of credibility to the throng of aid-funded grifters seeking to use any linkage with the word ‘Kokoda’ to enhance their own aid-funded earnings potential and career development at the expense of taxpayers. This was verified by the archaeologist in charge of the ‘discovery‘, Dr Matthew Kelly, when he admitted they adopted the term ‘lost battlefield’ because ‘it was a catchy title to get people’s attention‘.

The 80th anniversary of the heroic Kokoda campaign deserved better than ‘catchy titles’ and contrived versions of its history.

FOOTNOTE:

DFAT officials in PNG now seem to act as an unaccountable law unto themselves. Neither the Kokoda Initiative nor the PNG Kokoda Track Authority which they fund through the PNG Department of Environment, Conservation and Climate Change has ever published an annual financial report. As a result, key stakeholders have no idea where the money goes. Anecdotal evidence suggests most of it circulates in Port Moresby.

They also go out of their way to avoid working with the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Australian War Memorial regarding the protection and development of our shared wartime heritage across the Kokoda Trail.

In 2010 they reacted to a report of the discovery of a ‘lost battlefield’. But rather than engage the Department of Veterans Affairs which is responsible for both the Australian War Memorial and the Unrecovered War Casualties Unit – or any of the genuine military historians who lead treks across the Trail – they used an inner-circle of mates, consultants, and compliant eco-tour operators as their ‘experts’.

In 2016 they engaged a hipster promotion company to develop interpretive panels at Owers Corner. As a result, the term ‘friendship’ replaced ‘mateship’ while the panels contain incorrect and irrelevant information.

In 2017 they ignored the Australian War Memorial in their search for a National Military Heritage Advisor in PNG. They engaged an American anthropologist in a recruiting process that could best be described as ‘dodgy‘ – and one that would not certainly not pass muster with any watchdog agency in Australia.

Since 2022 they have been trying to sneak a ‘Kokoda Track Management Authority’ environment bill through the PNG Parliament via a process which has the all the hallmarks of ‘foreign interference’. If they are successful the Kokoda Trail, which is PNGs most popular tourism destination, will be managed as an aid-funded environmental resource for the benefit of foreign anthropologists, archeologists, and environmentalists, rather than as a commercial enterprise for the benefit of subsistence villagers who own the land sacred to our shared military heritage.

Lest We Forget