‘Just a day’s travel from Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane and you can be on the Kokoda Trail.

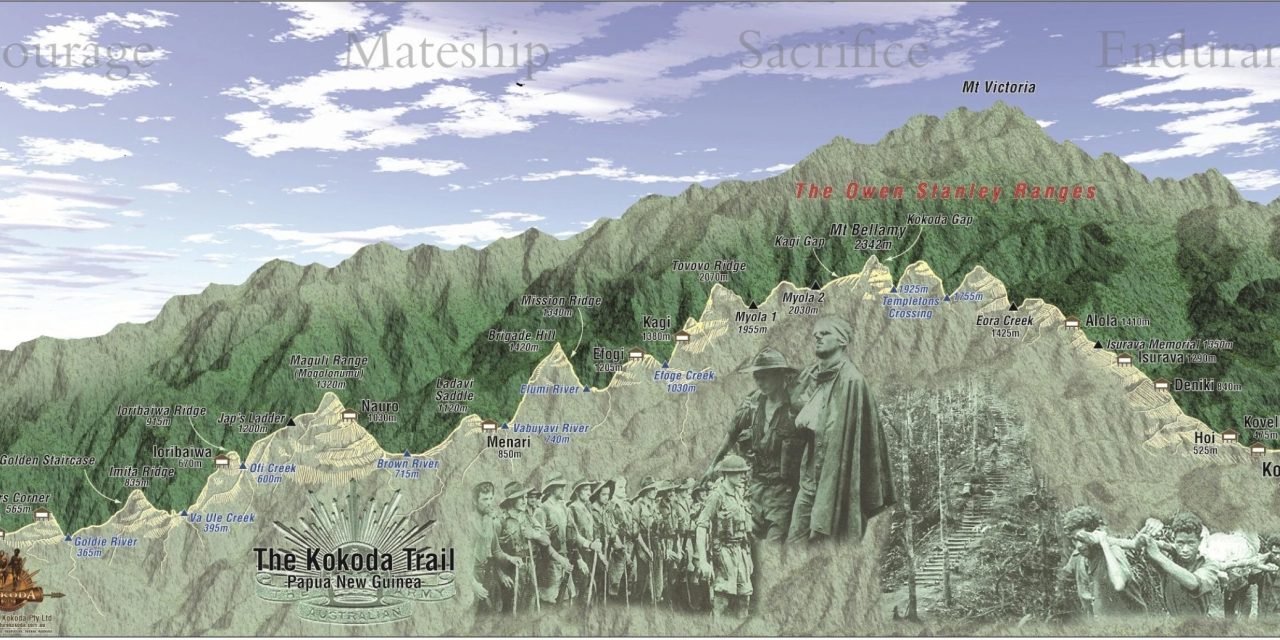

‘At the foot of the Owen Stanley Ranges in Papua New Guinea you can look into the ancient landscape – majestic peaceful wilderness, nature in its full glory.

‘‘There have been tracks across the mountains for thousands of years – the people who inhabit the region were gardening at the same time agriculture was developing in Ancient Egypt. The strength of natural and cultural heritage are beyond simple words; fascinating, awesome, daunting – world class.

‘Yet the battles of 1942 and the contemporary interest in ‘Kokoda’ are what have made it Papua New Guinea’s No.1 tourist attraction.

‘In 1942 it was Australians and Papua New Guineans fighting Japanese for what was then Australian land. Young men in a bloody struggle for ‘their land’. The battle has become folklore in Australia – a place of pilgrimage like Gallipoli, Villers-Bretonneux, Sandakan, Passchendaele.’

Michael pender – military heritage architect

Day 1: Flight to Port Moresby

Air Niugini has direct flights to Port Moresby from Brisbane and Cairns. There is a direct flight between Sydney and Port Moresby two days per week. Trekkers can book directly with Adventure Kokoda or make their own arrangements. Trekkers arranging connecting flights should plan on arriving at least three hours before the scheduled departure time – otherwise they might make the connection but their baggage won’t.

Your journey begins on arrival at Jackson’s Airfield in Port Moresby – capital city of ‘the land of the unexpected’.

Formerly known as 7-mile strip, Jackson’s airfield commemorates Squadron Leader John Jackson DFC, Commanding Officer of 75 Squadron, who was killed when Japanese fighters shot him down over Mount Lawes, to the north of the airstrip in April 1942. Today, Jackson’s Aerodrome is Port Moresby’s international airport.

On arrival at the airport you are met by our Adventure Kokoda staff who will co-ordinate your movement to your hotel by bus.

After check-in at the hotel you will get a chance to meet your fellow trekkers at a briefing session which will cover our system of operation on the trail; administrative and logistic arrangements; hints on packing your gear; medical and malarial precautions; village customs and protocols, security of your gear at the hotel while you are on the trail; and our daily routine during your trek.

During dinner everybody gets a chance to introduce themselves and have a yarn together.

After dinner we have a briefing on some interesting aspects of PNG – our closest neighbour, former mandated territory, wartime ally and fellow Commonwealth member. We then provide an overview of our strategic situation in 1942 and the events that led to our militia troops being dispatched to New Guinea.

Over the years Papua New Guinea has been referred to as the Land of the Unexpected with a Parliament of a Thousand Tribes. Some regard it as the Last Unknown. It is the second largest island in the world after Greenland.

In the 1800s the western half was annexed by the Netherlands; the north-eastern part by Germany and the south-eastern part by England. Today the former Netherlands area is known as West Papua and is now part of Indonesia. After World War 1 the League of Nations allocated the German area (New Guinea) and Papua to Australia as a mandated territory. Unlike the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory our new territorians, Papua New Guineans, required a passport to cross our borders.

Papua New Guinea was granted independence in 1975.

Today its population of 7.5 million shares 820 languages which equates to a quarter of those in the world. English, Pidgin and Motu are the most common throughout the country.

It’s a land of contrasts where ancient cultures struggle to understand the meaning of a hitherto unknown world presented to them in a remote village via a solar powered satellite dish. A land where arse-grass and penis gourds mix with Hugo Boss suits and Rolex watches. Where some men mined the hearts of volcanoes for gold while others worship the spirit of ancestral crocodiles. It is a place where ferociously decorated warriors battle over women, land and pigs, with bows and arrows and home-made shotguns. Where Asian loggers plunder ancient forests alongside Christian missionaries harvesting souls and where Australian Government bureaucrats try to imbue their antipodean canons upon a culture where blood and bribes are thicker than holy water.

We will enjoy the experience of two of these 850 cultures of Papua New Guinea during our pilgrimage – the Koiari and the Orokaiva.

‘The Koiari were a fine people, very dark skinned with a peculiar hair-do – a bun worn squarely on top of the head. Physically they were robust and more free from skin diseases than any other Papuan natives I had seen. Despite close proximity to Moresby, they had resisted the ‘civilising’ influence and until a few years ago the coast villagers lived in terror of their raids. The tribe showed surprisingly little resentment of the sudden and bewildering invasion of their domain by a white army. The men, accepting the patrol officer’s explanation that the Japanese were bad people who would loot their gardens and steal their women, were serving willingly on the carrier lines. The women were employed weaving palm thatch for troop shelters.’

The Owen Stanley Range is the south-eastern part of the central mountain-chain in Papua New Guinea. It was seen in 1849 by Captain Owen Stanley while surveying the south coast of Papua and is named after him. Strictly, the eastern extremity of the range is Mount Victoria 4,038 metres which was climbed by Sir William Macgregor in 1888.

The range is flanked by broken and difficult country, particularly on the south-western side. There are few practicable passes, one of which is the Kokoda Trail which crosses the range between Port Moresby and Buna and was in use for more than 50 years as a regular overland mail-route.

‘Before the war, the Kokoda Trail was considered to be passable only to natives, or officers of the Administration and ‘old hands’ accustomed to this primitive country, who were unencumbered on the march. The first Europeans known to cross over the Owen Stanleys were Sir William McGregor, a Governor of Queensland, and Albert Charles English, who made the crossing from Ioma over the range in the vicinity of Mt Victoria and Port Moresby.

‘It is probably centuries old – a main highway over the range – and in the usual manner of native pads, follows no established principles. It climbs the highest ridges, plunges down into the deepest ravines, and ascends the longest spurs. Between Uberi and the crest of the range, the track climbs more than 20,000 feet, although it has an altitude of 7,000 feet at its highest point. For every one thousand feet of altitude gained, the track drops six hundred feet to the foot of the next ascent.’[i]

Much to think about as you bunk down for the night at the hotel.

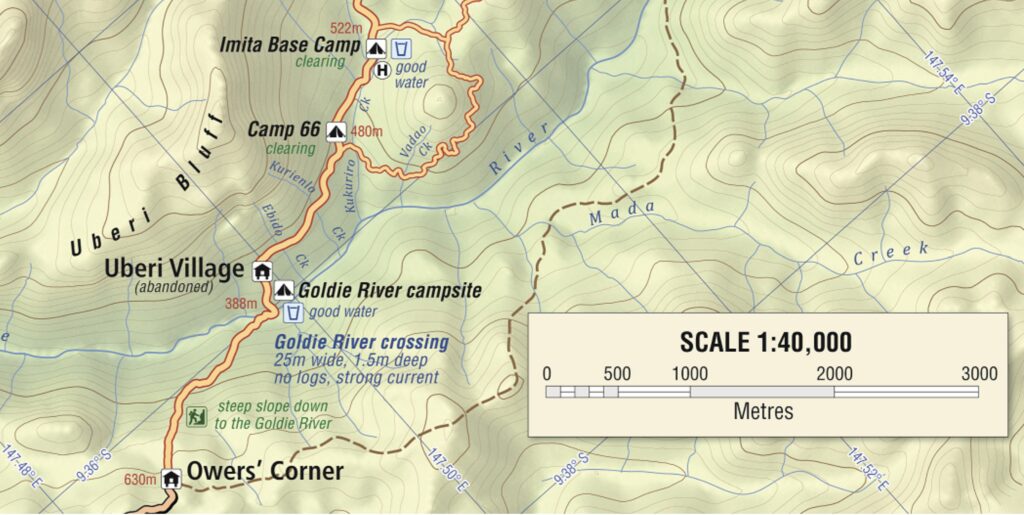

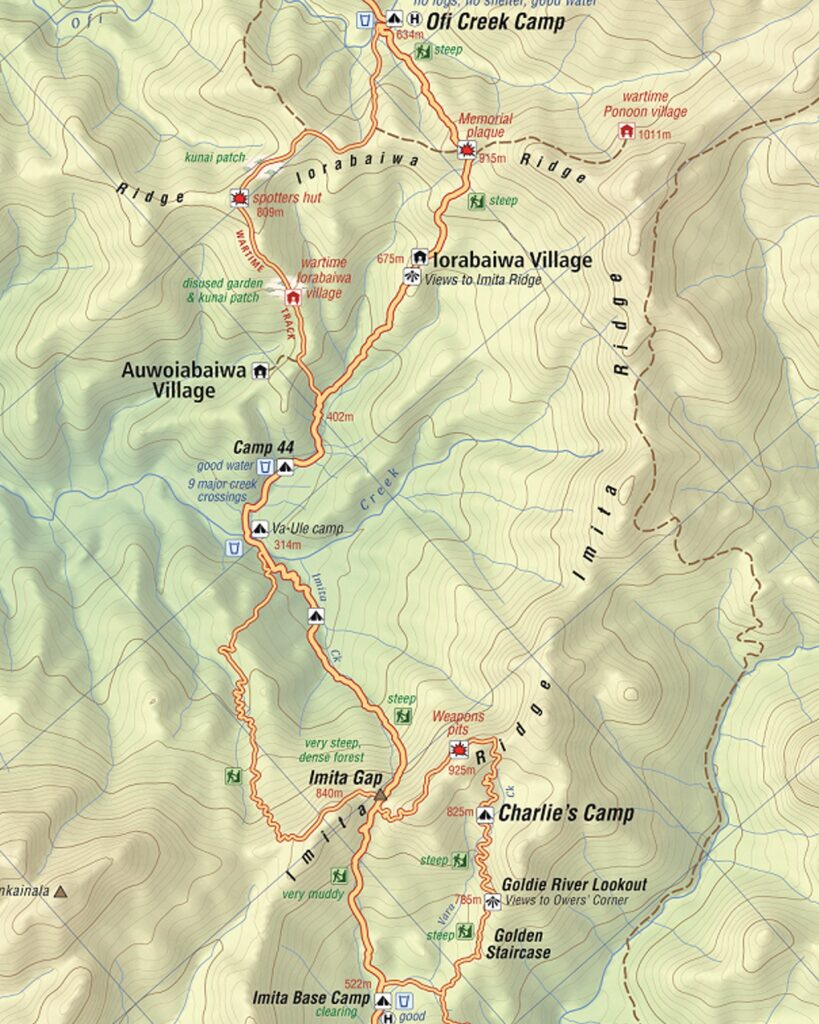

Day 2: Port Moresby – Owers Corner – Imita Base Camp

Distance: 5.3 kilometres – Climb: 252 metres – Descent: 372 metres

After breakfast we do a final check of our gear and board the bus for McDonald’s Corner on the Sogeri Plateau.

We cross the Laloki River below the lodge and pass a monument at the road junction at Depo (the location of a wartime army stores depot). Two kilometres along the road we pass the site of the Papuan Infantry Battalion Training Depot and a short distance beyond that was the Royal Papuan Constabulary Training Depot.

Five kilometres further along is McDonald’s Corner and the entrance to Ilola Plantation owned by Captain P.J. McDonald in 1942. This was the start of the pre-war Kokoda Trail.

P.J. McDonald was a Light Horse veteran from Gallipoli and a larger than life Territorian character. A carpenter by training, he arrived in the Territory in the early 1920’s and built the first stage of the Steamships Trading Company store in Port Moresby. He became famous for the generous hospitality he extended to our troops.After a briefing at the monument constructed by Captain McDonald’s son, Bob, as a tribute to our troops we continue in the bus to Owers Corner which is 635 meters Above Mean Sea Level (AMSL).

McDonald believed that much of the suffering of the Kokoda campaign could have been avoided. He had told the military authorities of another way to reach Buna and Gona on the north coast of Papua – a route that, if taken, would have enabled the Australians to hit the Japanese in their flank. His advice was ignored – as was all the later advice from our front-line battlefield commanders.

‘When war started the army built a ‘corduroy’ road of timber saplings laid side-by-side through to Owers Corner – a further 12 km along the track. This location is named after Lieutenant (later Captain) Noel ‘Jerry’ Owers, a surveyor of the New Guinea Volunteer rifles, who was given the task of surveying a road that would bypass Uberi, Imita Ridge with its ‘Golden Stairs’. It was an impossible task and the project was dropped in early October 1942 after the jeep route had been developed only as far as the “Goldie River. The junction of the new road and a walking track, which formed part of the original overland mail route coming in from Sogeri and Subitana further to the west, was called Owers Corner.’

This was the end of the road and the start of the trail in 1942. It was here finally that two 25 pounder artillery guns were located to provide heavy fire support to our troops for the first time in the Kokoda campaign. They were able to fire over the troops on Imita Ridge and directly onto the Japanese positions on Ioribaiwa Ridge 10 kilometres away. One of the troops later exclaimed ‘the sounds of the shells passing over our heads was music to our ears’.

Here we meet up with our Koiari and Orokaiva guides and carriers – grandsons of the famous fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ who will guide us safely across the trail just as their forebears did for our troops in 1942.

At Owers Corner the track descends to the Goldie River where the army built a rough track using horses and mules to haul supplies and one of the 25-pound guns (called that because that was the weight of the high-explosive shell they were able to fire directly onto the Japnese positions on Ioribaiwa Ridge) We follow the track down the ridge, across the Goldie River and up to Uberi.

After a briefing on the significance of the area we begin a 40 minute trek down to the Goldie River.at 401 m AMSL.

It is important to remember that from now every step we take will be on land owned by a community, family or tribe under their system of customary land ownership. If you are in any doubt about the correct protocols to be observed at any time ask one of our guides who will only be too willing to help you.

The Goldie River is named after Andrew Goldie, a Scots naturalist employed by a London nursery firm to gather exotic botanical specimens.[i] In 1877 Goldie was part of an expedition inland from Port Moresby to Hombrum Bluff. One of the New Caledonian kanaks in the party, Jimi, later approached Goldie and handed over what he thought was quartz with gold in it[ii]. News of the discovery later leaked out and resulted in a number of gold expeditions to the area. It is possible that Andrew Goldie’s exploration party in 1878 may have crossed the river where the Track goes today. In his journal Goldie recorded ‘the black sand of the river yielded gold at every prospect’.[iii] Of the river, he reported to the Royal Geographical Society he had named it the ‘Goldie River’, declining to elaborate on whether it was named after him or because the river was ‘goldy’.[iv] The Governor, Sir Hubert Murray, who recorded in 1912 in his Papua, or British New Guinea, gave a more informed viewpoint when he wrote, ‘Mr Goldie did a lot of collecting … on the river that bears his name.’[v]

We then have a 10 minute gradual climb to abandoned village site of Uberi, named after the Ebe or Eburi people[vi]. These people had resisted early European exploration inland from Port Moresby by attacking and repulsing early expeditions. In Hawthorne’s book on the Kokoda Trail he reports that the:

‘continuing defeats on white explorers, coupled with a rich bounty of discarded expedition supplies, had a stimulating effect on the warrior’s confidence. It led them to a belief their prowess in battle was exceptional and if no white man would come to their villages to fight (because of a government ban), they would go to the white man, or at least to other, friendlier, native tribes associated with the white man. Accordingly, they began to attack their weaker neighbours and ‘killed off most of the villagers around.[vii]

The village was used by the Australian New Guinea Administrative unit as a support area during the campaign – it was also a transit camp with up to 400 diggers jostling for position as new troops went forward and wounded troops returned from the front.

After Uberi we continue our gradual climb via a number of creeks – Abido, Koelo, Wiraro and Kukuiro – to our campsite on Lubu Creek at 510 meters AMSL where we settle in for our first night.

Day 3: Imita Base Camp to Ofi Creek via Imita & Ioribaiwa Ridges

Distance: 18.5 kilometres – Climb: 1193 metres – Descent: 1044 metres

A hearty breakfast will set you up for your first endurance test this morning – muesli, weet-bix, a variety of tinned fruits, biscuits (with jam, peanut butter, vegemite) and tea, coffee or hot chocolate.

After breakfast and briefing this morning we begin our first climb up Imita Ridge to the Imita Gap at 850 m AMSL.

‘The engineers cut more than 2,000 steps on this spur. Many men tried to count them, but soon lost interest in the figure from the breathless effort to reach the top. The narrow track seemed to go interminably upward. A glimpse of the sky through the trees ahead instinctively quickened men for a few paces, until the spot proved to be a false crest where the spur turned slightly to continue upward, its top still hundreds of feet above. This prelude to the Owen Stanley Ranges was known as the ’Golden Stairs’.

The track climbed to a saddle on the Imita Range. There, on a small shelf, twenty yards wide, it provided the weary soldier with a superb but disheartening panorama of the country beyond. Across the valley lay another ridge like the one he had scaled, and another beyond, and more, each clad with jungle except for a distant patch of kunai and a few native huts. Apprehensively, the soldier knew this to be Ioribaiwa, the end of that day’s march.

‘From the Imita saddle, the track plunged steeply down another narrow, knife-like ridge, which fell into a stream one thousand feet below.’[i]

On the northern side of Imita Gap there is a steep descent to Imita Creek. It was here that Albert Moore set up a Salvation Army shelter to prepare soup, hot tea, biscuits and scones for weary troops passing by.

| Charlie Lynn grew up in Orbost, a small town on the Snowy River in Gippsland. The local milkman and Salvation Army Officer was Albert Moore. Charlie did not know he was a hero of Kokoda until they met at ‘The Last Parade’ he helped organise at Isurava in 1998 – 31 years after he was conscripted into the army from Orbost. How many of us grew up amongst these ‘silent heroes’ without ever knowing it? |

The trail continues down to Imita creek and from here it meanders back and forth across the creek for about almost an hour before it reaches Va Ule Creek (formerly know as Munikahila Creek). You are now entering the jungle and will notice a large variety of trees with enormous buttressed roots to help them keep a foothold on the sharp slopes and eternally sodden soil. The struggle for survival in this rain forest is fierce. Growth, decay and death are all rapid so that the parasites and saprophytes luxuriat in the thickening canopy of creepers bearing strange flowers and fruits. In the lower levels of the Owen Stanleys grow wild nutmeg trees, taun, kwila, erima, rosewoods, mahoganies and New Guinea walnut. Higher up are red cedars, beeches, oaks, and isolated stands of Klinkii and hoop pines reaching 90 metres. Many of these trees are deciduous.[ii]

We stop for lunch at the Va Ule campsite and take time out for a refreshing swim.

After lunch we continue to criss-cross Imita Creek and pass the junction of ‘Ask Eric Creek’ to the base of Ioribaiwa Ridge at the junction of Imita and Morau Creeks.

We then have a fairly steep climb for about an hour without much relief to Ioribaiwa Village which is at 580 m AMSL. Glimpses back across Imita Ridge on the way up give the trekker a good feel for the awesome nature of the terrain. Weapon pits can still be found on the southern slopes. Today the wartime village of Ioribaiwa has five huts and is about 10 minutes off the main track.

‘Gradually men dropped out utterly exhausted – just couldn’t go on. You’d come to a group of men and say ‘Come on! We must go on.’ But it was physically impossible to move – many were lying down and had been sick … many made several trips up the last slope helping others. We began to see some of the tremendous effort the troops were going to make to help the lesser ones in. Found many of the battalion (at Ioribaiwa) lying exhausted, some ate, others lay and were sick, others just lay. Some tried to eat but couldn’t.[iii]

After a welcome morning tea break we continue our climb for another hour until we reach the crest of Ioribaiwa Ridge. This is as far as the Japanese got in their advance towards Port Moresby.

Our briefing here will examines the battle for Ioribaiwa Ridge at 825 m AMSL; the unexpected order for the Japanese forces to withdraw to the beachhead areas of Buna and Gona while their High Command waited the outcome of the battle at Guadalcanal; the confusion caused by the fresh Australian Brigade failing to establish a firm base on Imita Ridge; the undue caution this caused; and the crisis created in Australia when Brigadier Ken Eather asked for permission to withdraw to Imita Ridge.

Historians are yet to examine the implications of Brigadier Eather’s four day delay in attacking Ioribaiwa Ridge. How many Australians were killed at Templeton’s Crossing-Eora Creek-Buna and Gona because of the additional time this gave the Japanese to prepare their defensive killing grounds’.

After our briefing at the top we have a steep 35 minute descent down to our campsite at Ofi Creek at 625 m AMSL – it boasts one of the best swimming holes along the trail. Our ‘bos kuk’ will be waiting to serve you hot soup followed by canned meat and vegies on a bed of fluffy rice which you can wash down with tea, coffee or hot chocolate. You will sleep well tonight.

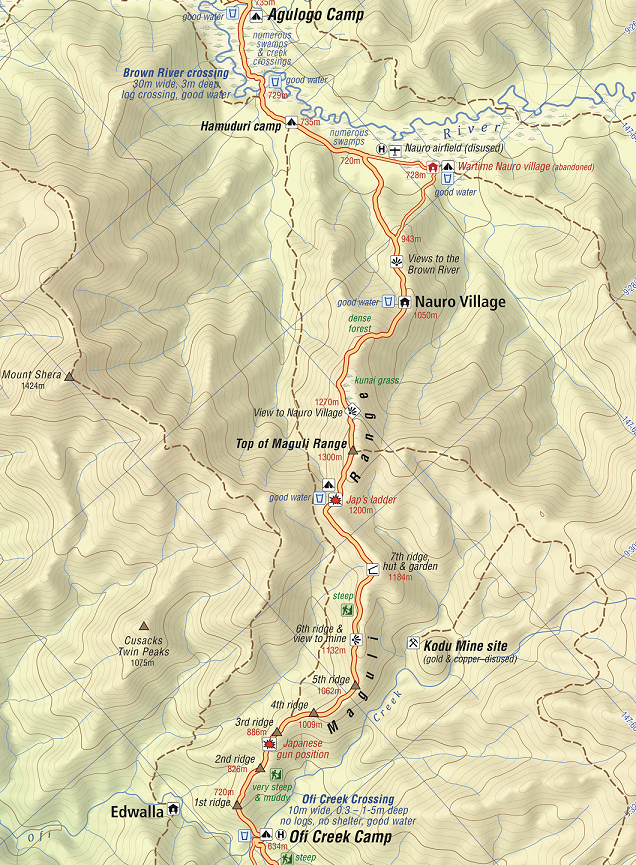

Day 4: Ofi Creek to Agulogo Creek Camp via the Maguli Range & Nauro Village

Distance: 18.5 kilometres – Climb: 1193 metres – Descent: 1044 metres

After our morning briefing we prepare ourselves for quite a gruelling three-and-a-half hour climb up the Maguli Range to Mogoronumu (the top of the ridge).

After 45 minutes up from the creek we reach a Japanese defensive position which dominates the track and overlooks a large area covered in a course spear grass known as kunai. Agronomists believe that these kunai patches, which cover many thousands of hectares, established themselves after primitive agriculture destroyed the forest. When trees are felled and undergrowth cleared, the rank kunai moves in so quickly that seedling trees cannot compete with it. It is an interesting layout with firing bays and a crawl trench between them. After a briefing at the position we continue our climb and soon begin to lose count of the false crests we encounter – each one taunting us into believing it might be the top.

Our engineers cut 3,400 steps into this side of the Maguli Range which became known as Engineers Ridge.

After a break at Mogoronumu at 1335 m AMSL we trek to the village of Nauro for lunch which is about an hour down from the top.

The new village of Nauro (formerly known as Wamai[i]) sits on a spur at 1000 metres and is home to about 80 people. The old village was located on the flat swampland at the base of the range to the north. It was abandoned in the early 1990s due to sorcery related issues within the clans. The village divided into Nauro 1 and 2 with each one now on adjacent ranges. The original village had an airfield which was abandoned and is now overgrown. A VHF radio is located in the village.

After lunch we trek down to the base of the range and enter the Nauro swamp area which is flat going through to our campsite at Agulogo Creek at 730 m AMSL. About half-an-hour from the base we arrive at the Brown River which was originally known by its native name of Manu Manu.

On 24 August 1878, while fording the new river, “Peter Brown, an original ‘Colonist’ man, heedless of advice, tried to swim the river” … “Alas”, as one of his comrades reported, “he went to the long home from which the explorer can never return. Two days later we found his body floating in the water. In sadness and sorrow we buried him on the bank of that lonely stream which will forever bear his name.[ii]

The crossing across this river still needs to be treated with caution if heavy rain has been falling in the catchment area. The crossing looks innocent enough but there is a very strong current adjacent to the bank.

Our campsite at Agulogo Creek is a further 15 minutes on from the Brown River. This campsite was carved out of the surrounding swamp area by a family from Menari. Adventure Kokoda provided them with finance to establish the area which is now one of the most beautiful and comfortable campsites on the trail. Agulogo Creek is pristine and popular with trekkers who get to enjoy a refreshing wash, swim and relax.

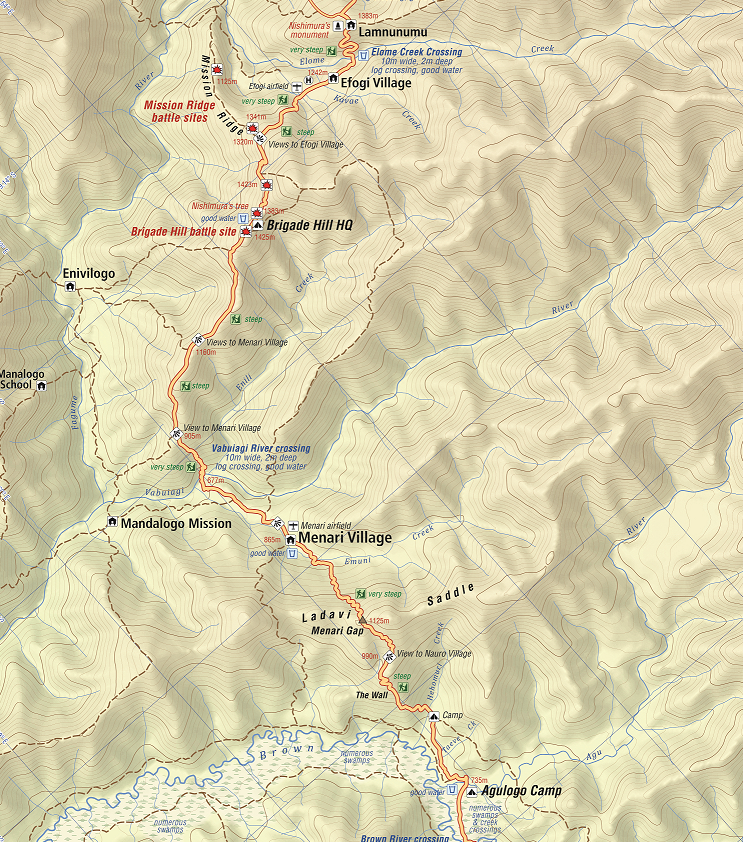

Day 5: Agulogo Creek Camp to Efogi Village Camp via Menari Village & Brigade Hill

Distance: 20.3 kilometres – Climb: 1530 metres – Descent: 1004 metres

Your briefing this morning will focus on the lead-up to the epic battle on Brigade Hill south of today’s destination at Efogi village. After our briefing we have a 25 minute trek through the swamp area to Five Creeks at the base of the Menari Ridge (not sure how it got its name as there is only one creek here where we pause to fill up our water bottles).

We now have a steep 50 minute climb to the Nauro lookout at 1040 m AMSL which has extensive views across the mountains we have crossed over the previous couple of days. From here we have another 35 minutes before we reach the crest of the ridge which is known as the Ladavi Saddle and/or the Menari Gap.at 1120 m AMSL.

Lunch will be waiting after a steep 45 minute descent to the Emuni River followed by a 10-minute walk up to the edge of the village at 865 m AMSL.

Menari is the second most populous village on the trail with around 250 people. It has a health centre, an elementary and primary school, a VHF radio station and an airfield and is home to the Wamai, Golebi and Uluve clans.

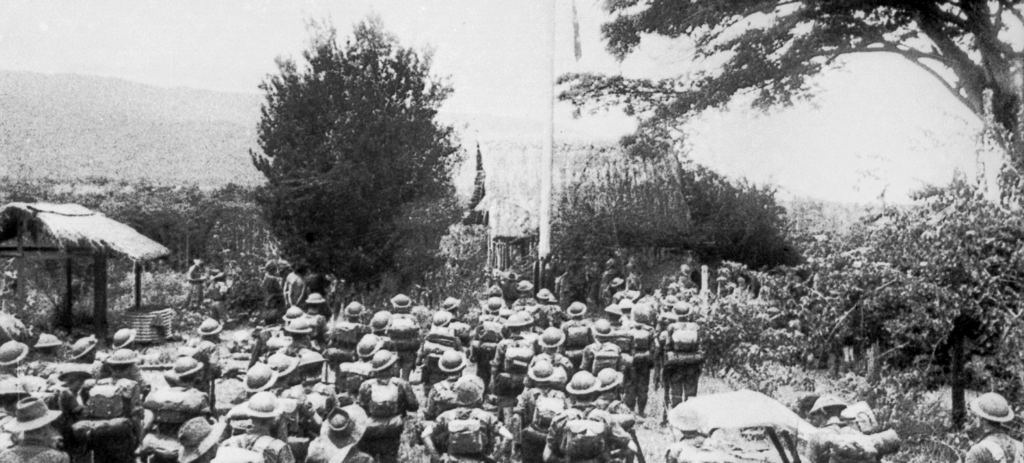

Menari is significant because it is here that Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, who took command of the 39th Battalion just prior to the battle for Isurava, held his first battalion parade. Damien Parer captured the parade on his award winning documentary ‘Front Line’ and it is featured on the front cover of Peter Brune’s book ‘Those Ragged Bloody Heroes.

Your trek leader will give a briefing which includes a copy of Lieutenant Colonel Honner’s address to his troops.

The track out of the village follows the airfield for about three-quarters of its length then branches into a garden area and down onto Vabuyavi River. There is a log bridge onto a large boulder in the centre of the river and a cane swing bridge on the other side. Trekkers need to exercise caution when crossing and should use their guides to assist.

From here we face a two-and-a-half hour grind to the top of Brigade Hill at 1415 m AMSL. About an hour and a half up from the Vabuyavi River is Tambunu – a track junction and lookout.

From here it is another hour to the top of Brigade Hill which was rediscovered by Charlie Lynn in 1992 when the landowner, Siosi Liami, led his group to a ‘special place’ where, as a 15 year old boy, he helped bury 72 Australians and one Japanese after a ‘big battle’. In fact it was the biggest battle of the Kokoda campaign where a force of 6,000 Japanese soldiers from the 144th South Seas Island Regiment under General T Horrii attacked a defending force of 1,000 soldiers from the Australian 21st Brigade under the command of Brigadier Arnold Potts on 8th September 1942. The Japanese refer to it as the battle for the Owen Stanley Range – the Australians call it the battle for Brigade Hill. The terms Brigade Hill and Mission Ridge and Butcher’s Ridge were to be emblazoned on the battle honours of the Australian battalions (2/14th, 2/16th and 2/27th) who fought here.

Brigadier Potts was a courageous commander and highly respected by his troops. However there are serious questions over the layout of his defensive position and the fact that his fighting patrols did not detect the enemy’s cut-off parties moving up the valley to the west of his position. These questions will be addressed by your trek leader at his briefing on the site of the Brigade headquarters position.

After the briefing we trek down into a saddle between the Brigade Headquarters and the 2/16th battalion position; we then skirt the 2/14th position before reaching Mission Ridge which was defended by the 2/27th Battlalion. It was later named ‘Butcher’s Ridge because of the carnage that took place during the battle which featured a heroic stand by the 2/27th under Lieutenant Colonel Cooper.

The wartime track leads down over Mission Ridge and up to the abandoned wartime village locations of Efogi and Kagi. Today’s track leads us down a steep ridge for about 25 minutes until we reach Efoge Creek. We then have a 10 minute trek up into the relocated village of Efogi which is the largest village along the trail with a population of around 350 from the Oagi, Eloki and Elomi clans.

Efogi has an airfield; a primary and secondary school; a health centre; a community campsite – and a large generator that is not connected to anything!

We camp at our Efogi Village campsite at 1215 m AMSL. We provide school material and sporting goods to around 20 orphans from the village each year. The orphans live with their ‘wan toks’ in the village but are usually at the end of the food chain in a subsistence village environment. The young ones like to sing for our groups in appreciation of the ‘presents’ we bring them.

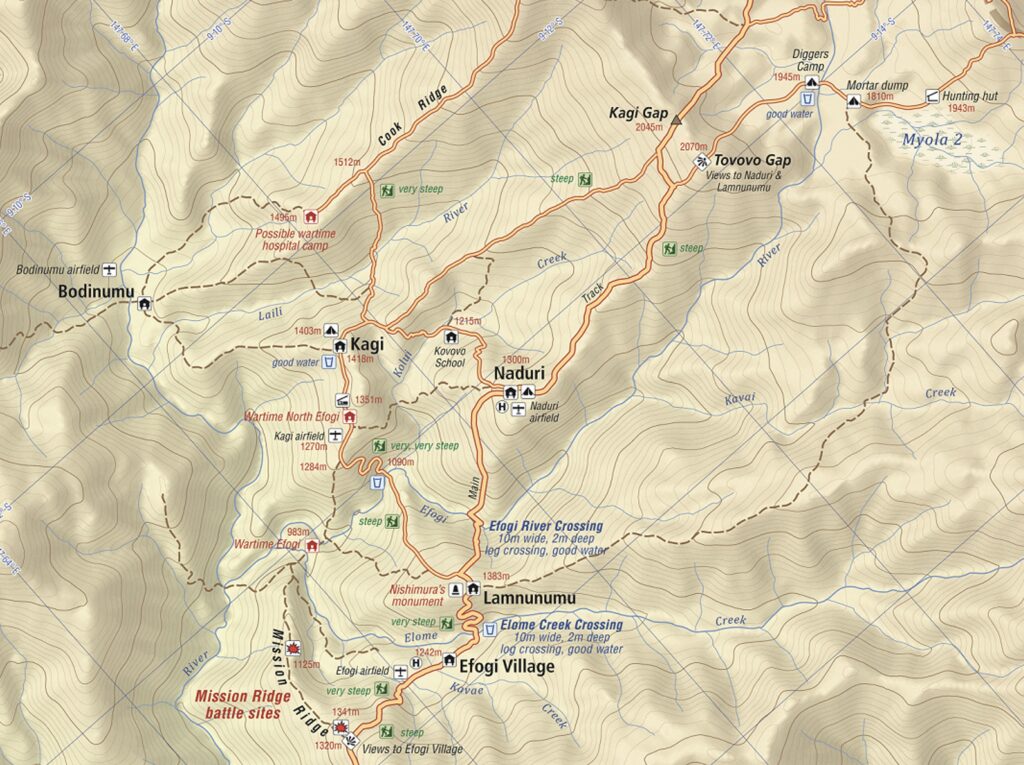

Day 6: Efogi Village Camp t0 Bomber’s Camp via Laununumu & Kagi Villages & the Kagi Gap

Distance: 21.8 kilometres – Climb: 758 metres – Descent: 273 metres

The track leading out of the village descends to the Kavai River before a sharp 25 minute climb to Efogi 2, or Launumu village. At the entrance to this village one can see the views the Japanese had of the Australian defensive positions on Mission Ridge as they crossed their start line on the evening of 5 September 1942. To the rear is the ‘forming up place’ where the Japanese would have formed up and completed their final battle procedures before crossing the start line for their attack on Brigade Hill.

Today there is a small Japanese monument in the centre of the village. It was erected by Corporal Nishimura, one of the few Japanese survivors who returned to the area 37 years after the war to recover the bodies of his comrades and release their spirits.

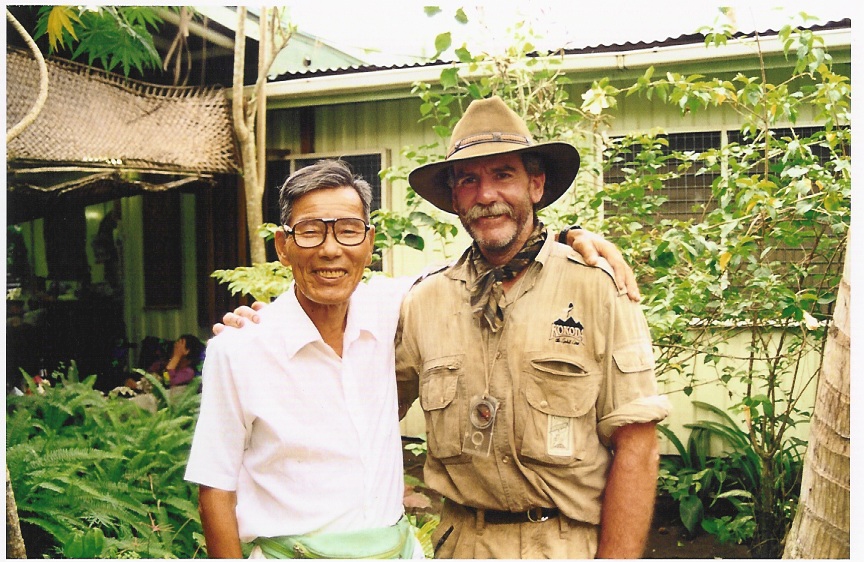

| In 1996, well before ‘Kokoda’ was discovered by all but a hardy bunch of trekkers each year, Charlie Lynn met with Japanese Corporal, Nishimura in Popondetta. A remarkable man who was the only survivor in his platoon and who pledged that if he survived he would return to the battlefield to recover the bodies of his comrades and release their spirits – he also dedicated a memorial to their sacrifice in Laununumu village. His story was later recorded in a book titled ‘The Boneman of Kokoda’. |

The track leading out of the village descends gently for about half-an-hour before it drops steeply to Efoge Creek. After crossing the creek there is a steep ascent to the village of Kagi (formerly known as Hagari[i]). This is probably the most ruggedly picturesque section of the trail.

Kagi village has approximately 120 people. It has an airfield, a VHF radio, water-points and guesthouse facilities. The Kagi people were identified by the early explorers (McGregor) as ‘a fighting, aggressive community[ii]’. They have since been converted by Seventh Day Adventist missionaries whose influence today is evident – they have a satellite dish on the top of the church but nothing on top of the school!

The wartime village of Kagi was located on the ridge to the south-west of the current village. South of the village is an airfield which has an interesting profile. The fuselage of a Cessna is a reminder of the hazards of flying in PNG.

The track out of Kagi leads northwards towards the Kagi Gap and into the moss forest area towards Mt Bellamy and the Kokoda Gap. About 10 minutes along this track from the village there is a junction with a track leading down into a valley where the school of Kovovo is located. This is the biggest village school along the Track. It has five teachers and 97 students who come from the surrounding villages of Efogi 1, Efogi 2, Kagi, Lamagi, Daoi, Envilogo, Naduri and Menari. It is situated on Kolui Creek.

| After a rugged trek from Efogi to Kagi Charlie Lynn’s grandson, Tom Claverotte, points to the climb ahead towards the Kagi Gap with disbelief |

We then have a long climb towards the clouds to the Kagi Gap. It takes about an hour-and-a-half to reach the lookout which has extensive views to the south coast. One could only imagine the thoughts of the Japanese soldiers as they saw their distant objective for the first time.

It takes another 20 minutes to reach the top of the ridge and enter the moss forest where:

‘a wonderland of giant trees festooned with flowering creepers bearing a bewildering mass of parasitic and saprophytic plants – orchids, staghorn ferns, and ‘mistle-toes’ of strange hue and shape. The sun’s light rarely penetrates to the floor of the jungle where hundreds of species of trees and thousands of species of smaller plants riot in disorderly variety all together. Because rainfall and humidity are higher the cycle of germination, growth, decay and death is faster. The forest lives on the product of its own wet rottenness. Mosses, ferns, lichens and fungi are everywhere. The moss forest can be an eerie place at night as large areas are infected with The trail through the area is wide, the moss covered ground is spongy, the views are spectacular and the mist that often pervades the forest is haunting’.

We then trek down to our Bomber’s campsite for the night. The campsite was developed by one of our former Adventure Kokoda trek leaders, Martin Rama, after the discovery of an American bomber aircraft in the mid-90s. The bodies of the crew were repatriated to the Unites States for a military burial at Arlington War Cemetery. A 500lb unexploded bomb was detonated creating a huge crater which is now filled with water. Parts of the aircraft can be seen near the crater. The campsite is the most picturesque of all along the trail. Temperatures drop to near freezing at certain times of the year because of the altitude at XXX m but Martin has rigged up two hot shower buckets which compensate for the cold.

We have a welcome surprise tonight – this is the half-way point where you can send in some treats to add to the evening meal – self-saucing chocolate pudding with a tube of condensed milk is a favourite of past trekkers. In addition to this we have fresh food supplies which we bring in by helicopter.

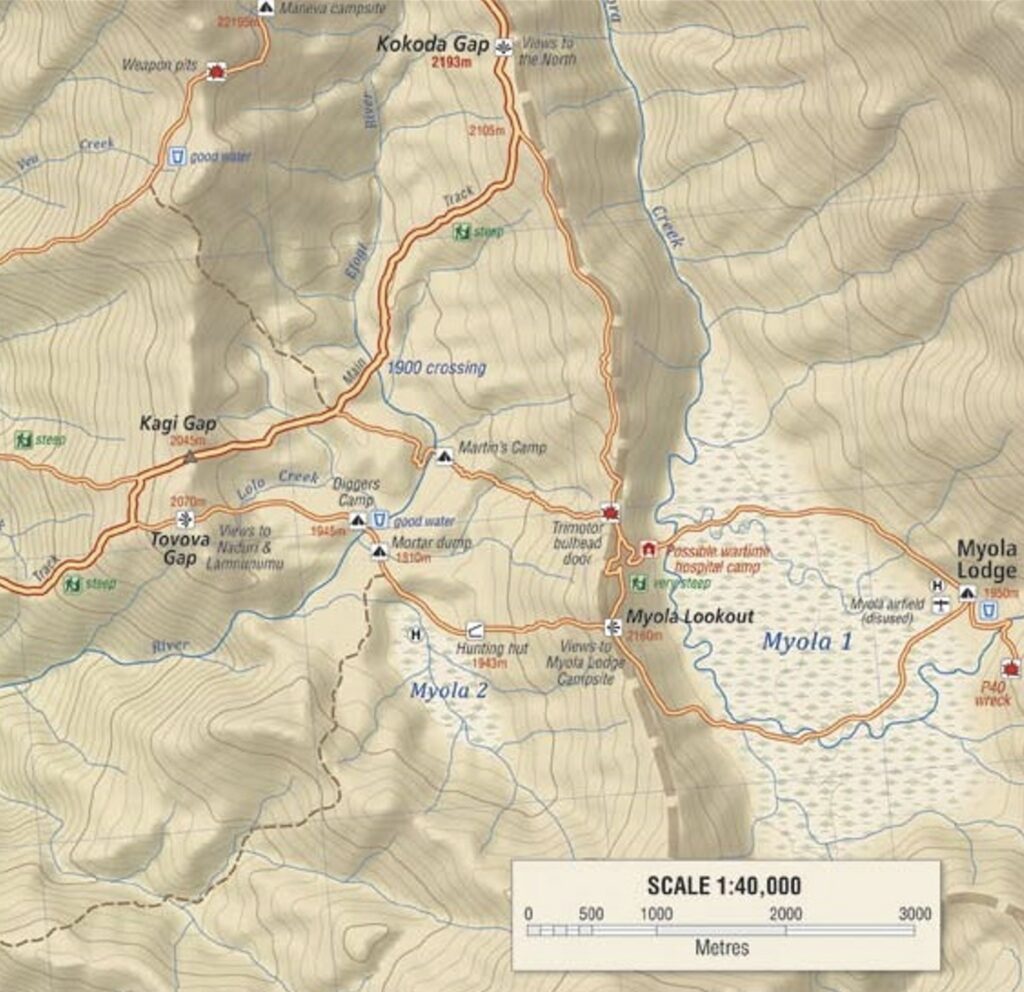

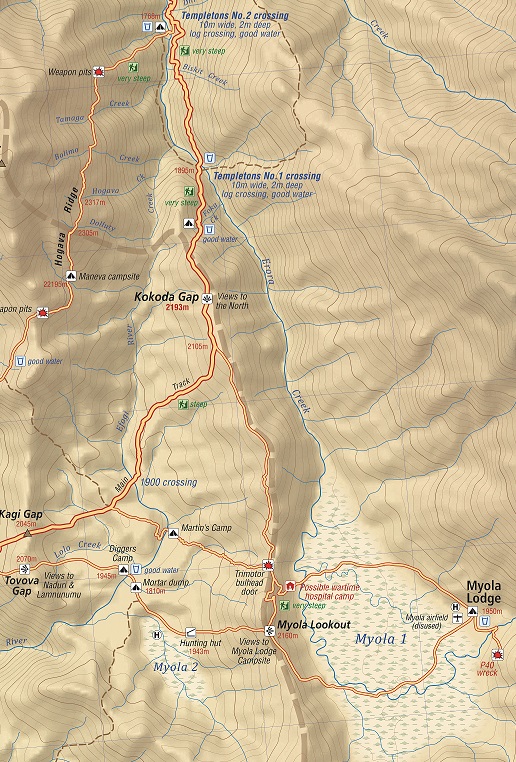

Day 7: Explore Lake Myola from Bomber’s Camp

Rather than trek to the edge of Lake Myola and ‘glance’ at it we have set aside a day to explore it. According to our past trekkers it is the most rewarding day of the trek because they feel they have truly ‘walked with ghosts’.

This experience is only available on our 10-day premium treks as the shorter treks do not allow sufficient time for the exploratory 6-hour trek across the two lake-beds and the 25-minute climb to the crashed P40E aircraft.

We start the day with real toast, poached eggs and your favourite spreads in addition to our normal carbo-loaded menu.

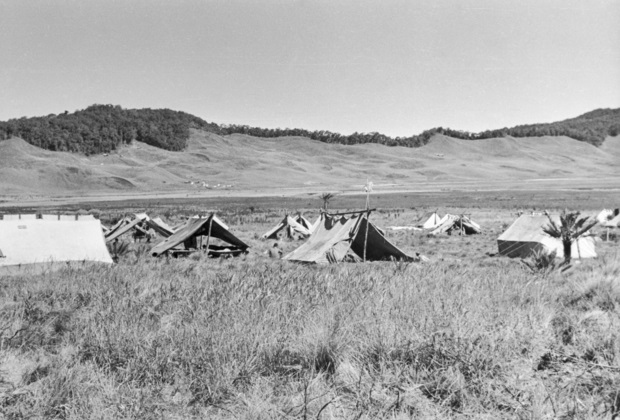

We then set out to explore the mystical volcanic lake-beds of Myola. From before time until war came to the area the local mountain Koiari people regarded this land as tabu because it differs so starkly from the surrounding jungle ranges extending far beyond their horizon. The lakes are nestled high in the Owen Stanley Ranges at 2145 metres which is almost as high as Mt Kosciuszko at 2228 meters.

The prairie like grassland is surrounded by some of some of the most enchanting moss forest one will ever experience. The border between the grassland and moss forest is so stark it could have come off a designer landscapers plan.

A crystal clear stream with fresh trout meanders around the lake bed area and flows into the upper reaches of the watershed for the Eora valley to the north. Near freezing temperatures collide with the atmosphere created by clear morning skies to create an ever-changing kaleidoscope of misty cloud formations that rise from the grassland each morning.

The solitude of this magical place was shattered when Lieutenant Bert Kienzle cut his way out of the jungle to discover the area. Kienzle, a plantation owner from Kokoda had enlisted in the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU) and had previously spotted the lake beds from the air during his frequent flights between Port Moresby and Kokoda. When he was tasked to establish a supply base along the trail he cut his way in from the native mail track east of Mt Bellamy along what is now known as Myola Ridge.

Kienzle named the area Myola after the wife of his commanding officer) – an aboriginal term meaning ‘break of day’. Nearby, and at a higher altitude, was a second dry lake, which became known as Myola 2.

Your briefing this morning will focus on the decision of Brigadier Potts to abandon his logistical area at Lake Myola due to the impossibility of defending against an advancing enemy. It was obvious to Potts that the enemy commander had too many options to pin them in location and bypass them with a larger force heading directly to Port Moresby. He then withdrew his battle weary troops south to the crest of the range and further on to a dominating feature south of Efogi which was to become known as Brigade Hill.

We then take a short trek to through the moss forest to the edge of Myola 1. We pass a mortar ammunition dump that was discovered by Charlie Lynn in 2003 and move out onto the kunai grassland We trek across towards two hunting huts and re-enter the moss forest for a 25 minute climb to the edge of Myola 2.

We then follow a hunting track to the North-West crossing the upper reaches of Eora Creek before arriving at the edge of the disused airfield. From here it’s a half-hour trek up to the site of the crashed P40E Kittyhawk fighter.

On 22 November 1942 Lieutenant Ralph Wire of the US Army 9th Fighter Squadron flew his P40E Kittyhawk from 3 Mile Drome (Kila) near Port Moresby on a mission to escort transports bound for Dobodura Airfield. During the flight, Wire was forced to leave the mission early due to his engine overheating and and crash-land near Myola.

Wire parachuted to the ground safely and landed unhurt. The official history of the 2/1st Battalion ‘The First at War’ recorded an eyewitness account of the crash:

‘The next day an American Kittyhawk fighter, after circulating for awhile, tired to land with a back-firing engine. It ended up in the timber on the mountainside. That made two more patients (the other being the pilot of the Ford Trimotor that crashed the day before). The American fighter pilot was bashed in the face in the crash and the next day, before being operated on, produced a photo of himself and told the surgeon ‘to try and make him look like that’.

The Curtiss P-40E fighter was a single-seat aircraft powered by a V12 Allison In-line liquid cooled engine. It was armed with six M2 0.50 inch calibre Browning machine guns, mounted in the wings – these are visible on the Lieutenant Wire’s crashed P40E Kittyhawk on the northern edge of Myola 2.

We then retrace out steps to the guesthouse area owned by the people of Naduri before entering one of the most beautiful areas on the trail which takes us to the northern edge of Myola 2. From here we ‘walk among ghosts’ as we cross the area where the 14th and 2/14th Field Ambulances set up a crude tented hospital area under Major Rupert Magarey. By the end of October 1942 there were 150 stretcher cases and about 300 walking wounded with dozens coming in every day as a result of the fighting at Templeton’s Crossing and Eora Creek.

Nearby was the logistic base which was primarily supplied by the famous ‘biscuit bomber’ – Dakota C47 transport aircraft that pioneered a new form of aerial resupply by parachute and free-drop. The area was abandoned in the face of the rapid Japanese advance in late August 1942 and re-occupied again by the Australians during their advance back across the Track in pursuit of the fleeing Japanese forces in early October 1942.

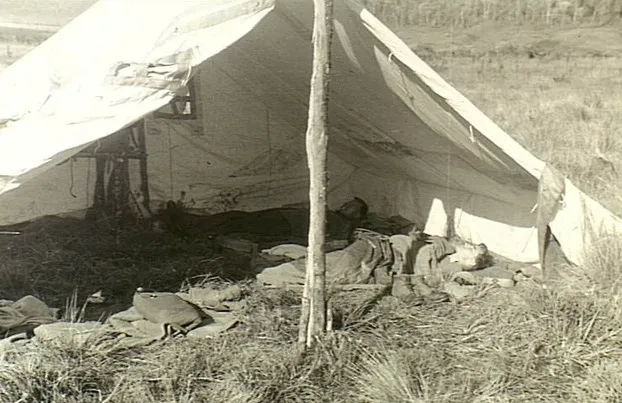

Doctor’s resting in their quarters after an all-night emergency duty

It was hoped that a landing strip could be cut that would allow casualties to be evacuated by plane, but the first light plane did not land until late October. However, there were insufficient light planes and several crashed on landing at Myola. Only about 40 casualties were flown out of the mountains and the rest were left to languish under crude canvas shelters.

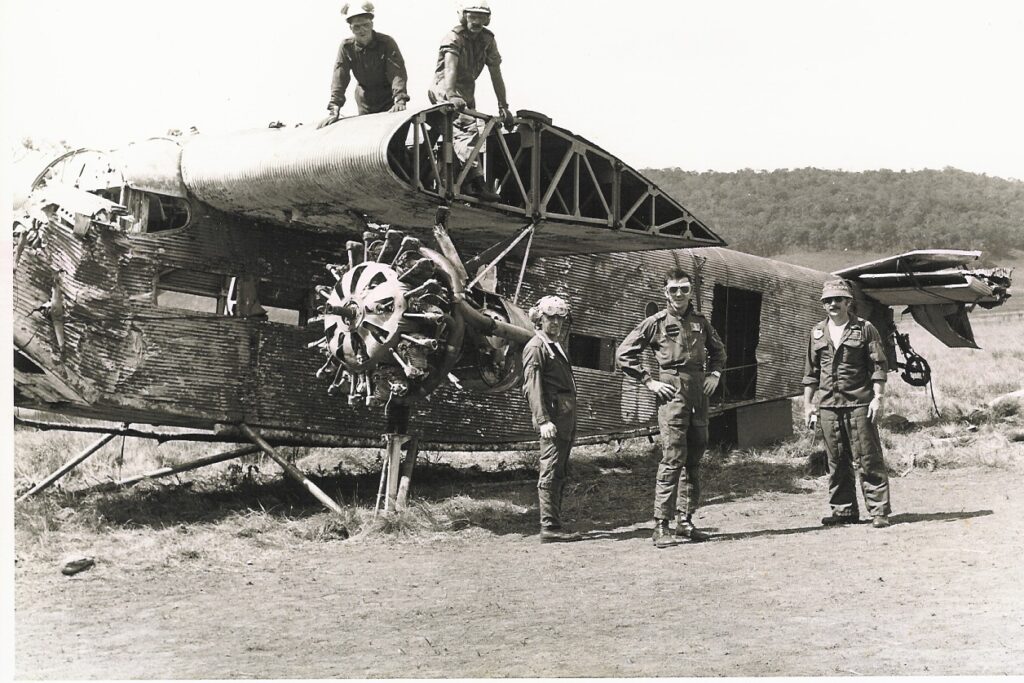

One of the aircraft that crashed was a Ford Trimotor which was originally owned by the Earl of Lovelace in East Africa. It was later sold to Guinea Airways in New Guinea in 1935 and operated in civilian service 1942. These aircraft were affectionately known as the Tin Goose because they were built from corrugated iron.

The RAAF took control of the two trimotors owned by Guinea Airways and had them converted into air ambulances. They were then used for the evacuation of troops from Lake Myola during the Kokoda campaign.

On 24 November 1942 A New Guinea Airways Civil Pilot, Tom O’Dea, airlifted eight patients out of Lake Myola. The 2/1st Battalion reported:

‘Everyone watched him take off and just clear the western lip of the ridge which was the spur dividing the two lakes. Later that day he came back and, before he came in to land, someone had moved the markers at the end of the strip, evidently to lengthen it. He glided in to land, put his wheels right down between the markers, and bogged, and the plane somersaulted on to its back. O’Dea was carried out and became a patient at the MDS’.

In 1979 Major Charlie Lynn (top right) was tasked to lead a team of riggers to recover the Ford Trimotor that had crashed at Myola 2. The aircraft was recovered to Port Moresby and has been relocated to the PNG National Museum and Art Gallery in Port Moresby.

There was a reluctance to use aircraft to evacuate the hundreds of sick and wounded in the tented hospitals at Myola 2 and they were eventually ordered to get up and walk back to Port Moresby – some had been hospitalised for more than two months by this stage. Field hospitals along the track were tasked to assist them in their agonising ordeal. Troops were sent back in batches. A diary entry by one of the soldiers on 2 November bore witness to the evacuation:

‘Two arm-wounded men passed us . . . one had been shot in the elbow and the arteries cut. They had been tied but the exertion of the fast walk had busted the tyings and he was fast bleeding to death – blood everywhere. Tourniquet applied in double quick time and we carried him in. A few anxious moments when he very often blacked out. After about ½ hour we came to his cobber . . . in exactly the same condition . . . We got them to Uberi and they lived but only just.’

Morning tea will be waiting for us at the southern edge of the Myola 2 – we then re-enter the moss forest and return to our base at Bombers campsite for a late lunch. The afternoon is then free for ‘make and mend’ – a hot shower – a chance to clean and dry our gear and a yarn around the fire before dinner . . .

then goodnight!

Day 8: Bomber’s Camp to Templeton’s Crossing via Mt Bellamy, the Kokoda Gap, Myola Ridge & Crossing 1

Distance: 19.0 kilometres – Climb: 844 metres – Descent: 1018 metres

After lunch we trek along the Kienzle track for 90 minutes until we join the main track between Mt Bellamy and the Kokoda Gap at 2,245 meters AMSL. Along this section we cross the highest point of our trek at 2,320 metres AMSL and continue our trek down to the Kokoda Gap.

The Gap was first discovered by Sir William McGregor, Lieutenant Governor of British New Guinea from 1888 to 1898. McGregor led the first successful expedition of British New Guinea in 1896. On 1st September he reached the summit of Mt Scratchley to the west and observed:

‘Some half-score of miles (about 16 kilometres) east of Mt. Victoria, there is a depression in the Owen Stanley Range, the bottom of which appears to be a narrow glen, and at an altitude of probably 5,000 or 6,000 feet (about 1500 to 1800 metres). One seemed to be able to see along this glen in a southerly or south-easterly direction for twelve to fifteen miles (19-24 kilometres). The mountains on either side of it rise several thousand feet higher.[i]’

The Kokoda Gap at 2,190 meters AMSL is significant for two reasons. The first is that there is a spectacular view back down the Yodda Valley towards Kokoda. The second is because an anonymous armchair general from his faraway Melbourne headquarters ordered the troops conducting a fighting withdrawal from Isurava to ‘blow the gap’. He had obviously studied the battle of Thermopylae where a small force of 7,000 Greeks defended a narrow pass against an invading Persian army of 100,000 in 490 BC. Trouble was the name ‘Kokoda Gap’ on the northern side of the Owen Stanley Ranges and the ‘Kagi Gap’ on the southern side were identified as features by pilots flying between Port Moresby and Kokoda. The gap in the range is approximately 11 km wide and our diggers just didn’t have enough dynamite in their backpacks to ‘blow it’! This was typical of the ignorant crap they had to put up with during the campaign.

We take a break at the Gap and take in the view down the Yodda Valley to Kokoda and beyond. The track along the ridges to the west was allocated to the 39th Militia Battalion. The parallel track along the ridges to the east was allocated to the 53rd Militia Battalion. Both units belonged to the Australian 30th Infantry Brigade headquartered in Port Moresby.

We then have a 40-minute trek down to Crossing 1 where we take a break for afternoon tea.

Your briefing here marks the commencement of the Templeton’s Crossing campaign fought between here and the crossing at Eora Creek further to the North between 12 and 29 October 1942. It was to be most bitter and gruesome campaign.

After the creek crossing there is a good climb for about 45 minutes to the Boili Mail Exchange Point 2015 m AMSLwhere mailbags from Port Moresby and Popondetta were exchanged between mail carriers. We then have a 30-minute trek down to our campsite at Templeton’s Crossing at 1,760 meters AMSL. This is the point where the original track taken by the 39th Battalion converges with the track which was cut down from Myola Ridge via the Kokoda Gap and Crossing 1 after Lake Myola was discovered.

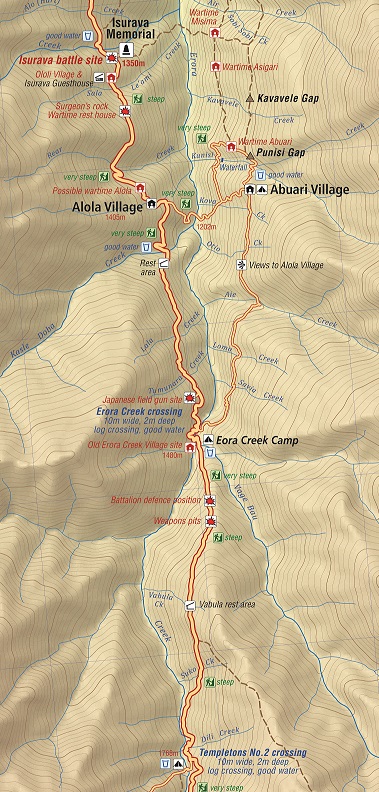

Day 9: Templeton’s Crossing to the Isurava Memorial Battlesite via Vabula Ridge, Eora Creek & Alola Village

Distance: 18.5 kilometres – Climb: 764 metres – Descent: 1450 metres

Your briefing this morning will focus on the significance of the area between Templeton’s Crossing and Eora Creek. The Japanese were ordered by higher command to withdrew from Ioribaiwa Ridge back to the beach-heads at Buna and Gona because of the strategic shift to the Solomon Islands where 36,000 Japanese were engaged in a massive battle against 60,000 American troops.

General Horii reluctantly accepted the order but remained alert to the possibility of stopping the Australian advance and continuing his quest to capture Port Moresby. With this in mind he established heavily fortified positions bristling with machine guns. They were well camouflaged with well selected killing grounds connected with communications trenches.

For the advancing Australian scouts it was lethal as they could not see the camouflaged machine gun muzzles protruding from their firing slits until it was too late.

The defences were such that it took the Australians 13 days to fight their way through an area that takes us half-a-day to trek today.

As we begin our trek towards Eora Creek you will understand why it would have been so difficult for the Australians to fight given the rugged terrain and natural camouflage.

We stop for morning tea on Vagebau Creek then continue to the crest of Vabula Ridge at 1,905 meters AMSL. The scenery as we begin our trek down the ridge is spectacular. We arrive at a knoll which was used by the Australian 2/14th and 2/16th battalions as a delaying defensive position during their desperate withdrawal on the night of 1 September 1942. Your trek leader will provide a briefing on the position from the front weapon pit.

We then proceed to an Australian mortar position where you will see live ammunition – 3 inch mortars and M36 hand grenades stacked beside a pit. Please do not touch.

We then trek down a steep spur with weapon pits on each side of the track before we reach the abandoned village site of Eora (formerly known as Iuoro).at 1,450 meters AMSL.

Henry Hamilton Stuart-Russell was the first European to pass through the Kokoda Gap on his way north and reach this point on 1 July 1899. Here he found the natives to be ‘friendly and hospitable’:

‘The old chief, Iovo, tried hard to dissuade us from going on to the Yodda Valley declaring we would all be killed. However, when he found we were resolved to go on, he personally escorted us some distance.’

Stuart-Russell’s party continued on until they met two natives fishing on a bank. The pair greeted the travellers cordially enough but half an hour later, the two men returned accompanied by 40 or fifty men,

Preceded fully 100 yards (about 90 meters) by their chief:

‘waving aloft a taro plant, he rushed right up to us – an instance of confidence that I have never seen before so boldly displayed, and at once dispelled any doubts I may have had as to our friendly reception’.

So convinced was Stuart-Russell of the natives’ peaceful intentions he moved his camp the following morning to a hill near their village. During the afternoon however, a ‘change set it’, as he put it, and after a rifle was snatched up and an unsuccessful attempt was made to fire it, the surveyor realised he was in a precarious situation. Stuart-Russell later reported:

‘Men came pouring in, from all quarters, armed to the teeth; the discharge of that rifle would have been the signal for a general attack, in which we would have had a very slender chance’.

Consequently, Stuart-Russell commenced his withdrawal, at first without conflict but while crossing the Mambare, the party was attacked:

‘Looking back as far as I could see was a forest of spears and clubs … Though they came on again and again with the usual bravery of all natives belonging to that district, they were repulsed every time with loss, and eventually drew off, not a man in my party having been injured.'[i]

A little over 43 years later another desperate battle was being fought. One can only imagine the chaos at this village as the Australians desperately tried to hold off the Japanese to but time for them to evacuate the wounded back up the track. Tragically they were not able to get them all out and some had to be left behind.

For reasons known only to the Australian Government there is no interpretive memorial at Eora Creek but if trees could talk they would tell of the most harrowing experiences of our wounded troops trying to escape the advancing Japanese. As they began to cross the raging creek below the situation for the stretcher cases lying in the mud was desperate:

‘Dr Magarey addressed the dozens of besmeared faces blinking up from the mud: ‘I want every man who is capable of walking . . . to start off for the top of the hill. We haven’t got enough bearers to carry everybody, but this place must be cleared tonight.[ii] The stretchered troops were told to drag themselves out. ‘A personal appeal was made to the men to walk, even if only for a few 100 yards without assistance’[iii].

‘Like slave drivers we urged them on, some hobbling, some staggering like drunks,’ remembered Steward. ‘They slithered, crawled and clawed their way through the mud, faces twisted with effort . . . Men can rise from dreadful pain to superlative heights .’[iv]’

All but three stretcher cases were evacuated from Eora during that desperate pre-dawn struggle. These badly injured men – two with abdominal wounds, one with an open chest wound – were given up for dead. Dr Magarey calculated they had half an hour to live. Later a medical patrol returned and found one of these men miraculously alive. The youth opened his eyes and asked an officer, ‘You’re not going to leave me here, sir? I won’t be left behind?’[v]

Magarey arranged to get the boy out – which was done – and he lived for several days on the shoulders of the fuzzy wuzzy angels.[vi]

‘Time and rain and the jungle will obliterate this little native pad; but for ever more will live the memory of weary men who have passed this way’.

Major-General Sir Kingsley Norris

Eora Creek is the most hazardous crossing along the trail and extreme care must be taken. Your guides will check the bridges and reinforce them with rope – they will carry your backpacks across and individually escort each trekker to the other side if the level of the creek has increased due to rain in the area.

We now leave the main track and take the route up the eastern side of the range to Abuari village.

This is one of the most primeval sections of your trek as very few take this route. Large buttressed tree roots, moss covered rocks and cascading creeks – Ovaveu, Oiba, Lomotaote, Savea and Ai provide a haunting setting as the morning mist sweeps up the valley. After Ai Creek there is a short climb to the edge of the ridge where the track now runs parallel to the main track on the western side of the range until it reaches Abuari village.

Abuari is off the beaten track and is a far more traditional village than those that have been exposed to trekkers over the past decade.

The village was relocated to the current site after the war and sits on the side of a large mountain at 1,550 meters. You cannot move around the village without climbing somewhere, Our campsite is towards the centre of the village. Those who take the 10 minute walk to ‘Abuari Heights’ will observe a scene of subsistence beauty that landscape architects would find difficult to replicate.

Northwards and downwards from the campsite is the heart of the village with a modern school built by Rotary International; a traditional elementary school built by the villagers and a health centre with expansive views down the Yodda Valley towards Kokoda.

Your trek leader will provide a briefing on the unsuccessful defence of the eastern side of the range by the 53rd and 2/16th battalions at Abuari and Missima. He will explain the implications of the defeat on the desperate battle for Isurava which had been raging for four days on the other side of the range. Brigadier Arnold Potts was forced to withdraw all of his force further back along the trail because they were in danger of being cut off from the eastern flank.

We then trek down to the Abuari – Waterfall track junction at 1,330 metres AMSL. It was here that the Commanding Officer of the 53rd Battalion made an ill-feted decision to follow up his troops believing that the trail down to the waterfall had been cleared. Unfortunately this was not the case and Colonel Ward and his battalion headquarters walked into an ambush at the waterfall and were killed. Their bodies were never recovered.

Today Myaka Falls is a reminder of the awesome power and spectacular beauty of Mother Nature. Adventure Kokoda is the only trekking company that takes this diversion to a forgotten phase of the Kokoda campaign so those who go get to trek where few have been.

We then return to the junction and trek down to Eora Creek valley where we have two spectacular crossings which are transformed from a pristine watercourse to a raging, thunderous white-water obstacle during the wet season.

We wonder at the possibility of the transformation as we sit down to lunch prepared by our ‘bos-kuk’ on the edge of the creek.

We now have a steep 40 minute climb to the junction with the main track and another 20 minutes up to Alola at 1,400 meters AMSL – a small village with about 60 people from the Niguri Clan. It has a small campsite and is located on Kaeledaba Creek.

The track continues northwards out of the village. About 20 minutes along is a clear ridge where the wartime village of Alola was located. It is now an abandoned site. The track then follows the ridgeline across numerous creeks – Belave, Aya Dakatni, Evoya, and Ololi to the rear of the Isurava battlesite at Alo Creek (named ‘Back Creek’ by Lt Col Ralph Honner to delineate the rear of his defensive position).

The battlesite at 1,349 meters AMSL was rediscovered by Charlie Lynn in 1996 using Australian Army topographical maps, a GPS and local guides. The site was confirmed when Charlie brought some veterans from the 39th and 2/14th battalions to the site for a ‘Last Parade’ later that year. On the 60th anniversary of the campaign in 2002 Prime Ministers Sir Michael Somare and John Howard opened a solemn memorial at the site.

The memorial now has a spiritual presence – four granite pillars stand like silent sentinels on this sacred site – each engraved with a single word: Mateship – Sacrifice – Courage – Endurance. A haunting reminder of a desperate struggle against all the odds by a generation we will be forever indebted to.

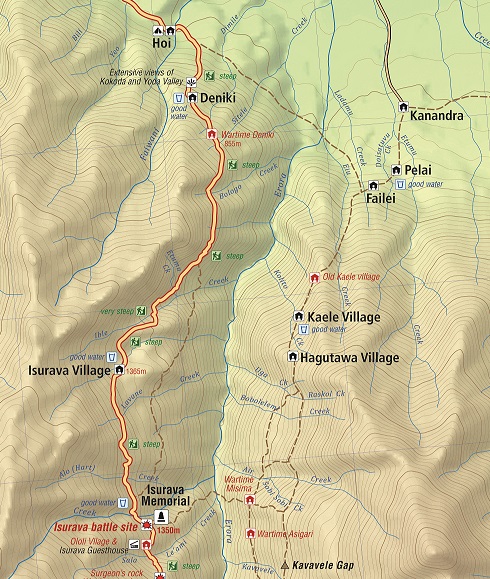

Day 10: Isurava Memorial Camp to Hoi Village Camp via Isurava Village

Distance: 12.5 km: Climb: 308 metres – Descent: 1016 metres

Reveille breaks the pre-dawn silence over the valley as we rouse ourselves for a haunting Dawn Service you will never forget.

In the pre-dawn light sleepy trekkers assemble quietly at the memorial. Out of the darkness they are joined by their guides and carriers who congregate around the granite pillars as your trek leader gives a briefing on the hellfire that lasted for four days between 26 and 30 August 1942. Every human quality that makes us such a proud nation was exhibited during this epic battle.

As the Australians were withdrawing from Kokoda more of their mates from the remainder of the 39th Battalion were making their way across track to reinforce them. Among them was Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner who was appointed as their new commander after the death of Lieutenant Colonel Owen. Honner was an intelligent, confident, courageous and well respected leader. He had great faith in his men and they never gave him reason to doubt his judgement. He had been ordered to hold the line at Isurava whilst the brass back in Australia belatedly decided the situation was now urgent enough to get our regular troops to the front line.

So Colonel Ralph Honner drew his line in the mud of Isurava just as Colonel Travis drew his line in the sand at the Alamo 106 years earlier. Unfortunately for Honner the odds his 39th Battalion faced at Isurava were about the same as the odds faced by the Texans at the Alamo!

‘Through the widening breach poured another flood of the attackers . . . met with Bren gun and Tommy gun, with bayonet and grenade, but still they came, to close with the buffet of fist and boot and rifle-butt, the steel of crashing helmets and of straining, strangling fingers. In this vicious fighting, man-to-man and hand-to-hand. Merrit’s men were in imminent peril of annihilation.’[i]

Our young warriors did not yield against the odds they faced during the hour of their peril. As the battle raged there were so many acts of courage and self-sacrifice that it is impossible to acknowledge them all. Even so the battle was to yield more Allied decorations than in any other single battle in the Pacific:

‘These were not blind heroics; they were calculated initiatives by Australian privates, corporals and platoon commanders determined to hold off the enemy as their units withdrew. Thus Private Wakefield, a Sydney wool worker, held up a Japanese charge as his section fell back; he won the Military Medal. Thus Captain Maurice Treacy, a shop assistant, ‘parried every thrust levelled at him’[ii]. He got a Military Cross. Though wounded in the hand and foot, Corporal ‘Teddy’ Bear, a die-cast operator from Moonee Ponds, killed a reported’15 Japanese with his Bren gun at point blank range’; he was later awarded the Military Medal and the DCM.[iii] Lieutenant Mason, a draughtsman, led his platoon in four counterattacks that afternoon; as did Lieutenant Butch Bissett, a jackeroo, whose platoon fought off fourteen Japanese charges.’[iv]

As the fate of the battalion hung in the balance a young Australian, Private Bruce Kingsbury, seized the initiative:

‘. . . He rushed forward firing his Bren light machine-gun from the hip, through terrific machine-gun fire, and succeeded in clearing a path through the enemy for the platoon; a courageous action which made it possible for us to recapture the position. He continued on, still sweeping the enemy positions with his Bren light machine-gun and inflicting an extremely high number of casualties on the enemy, but he was killed by a sniper hiding in the timber.’

Private Bruce Kingsbury was posthumously awarded the first Victoria Cross won on Australian territory.

Whilst the Australians suffered a tactical defeat their heroic stand against overwhelming odds caused the Japanese to suffer unacceptable casualties and use up valuable stocks of ammunition and supplies.

‘What made Isurava uniquely wretched in the annals of war was the devastating closeness of combat. The armies were fighting within earshot and, unlike their medieval forebears, with guns and grenades. ‘When the Japs were about ten feet away . . . I shrivelled up into almost nothing,’ recalled one private. Near the end of the Pacific War a US army medical team examined the effects of near point-blank fighting in jungle conditions. It found that more than 50 per cent of the casualties were struck at 25 yards or less, and nearly 85 per cent at 50 yards or less[v]. The wounds inflicted by a high velocity bullet at this distance can be imagined. Abdominal injuries were always fatal; shattered knees and limbs left the victim stranded. There were no helicopters. Hand-to-hand combat with fixed bayonets made the battle seem like ‘a knife fight out of the Stone Age’[vi].[vii]’

At the conclusion of the presentation your trek leader will conduct a Dawn Service that will live in your memory forever. Your guides and carriers provide a memorable finale as they sing a traditional songs and the PNG national anthem in exquisite harmony.

‘It is as if we have arrived. Somewhere, anywhere. Our guides sit with us, their families join us, and the village and its people become imprinted in our hearts. Another woman and I join the evening church service and are entranced as the pastor, his face illuminated by a hurricane lamp, recites the prayers in pidgin and the children’s voices rise in harmony so sweet we never want it to end’.[viii]

We return to our campsite for breakfast then continue our trek along the ridge via numerous creeks – Alo, Nobogolo, Kimaea, Kukuve and Subile for an hour until we enter Isurava village at 1,360 meters AMSL which was re-located to this site after the war.

After morning tea we begin our trek down Luboi Ridge towards the abandoned wartime village of Deniki at 865 meters AMSL via Ilole, Etume, Borogo, Botolo, and Selele creeks. A feature of our trek down the ridge is the number of abandoned native gardens that have been overgrown with choko vines. The 39th battalion fought a short but ferocious battle at this wartime position Deniki before being forced further back along the trail to Isurava.

A short distance further on we arrive at our lunch spot at Deniki (805 meters AMSL) where a couple of huts have recently been built to cater for trekkers. There are extensive views down the Yodda valley to Kokoda from here. ‘Foku’ is the local name for the area which has Okari trees (with edible nuts) on the site.

After lunch we have a short 20 minute trek down to our campsite on a beautiful creek at Hoi village which is 505 meters AMSL.

The locals usually provide a feast of fresh coconuts, papaya, bananas, pineapple and fresh scones. Hoi is known for its beautiful butterflies by day and its fireflies which light up the campsite at night.

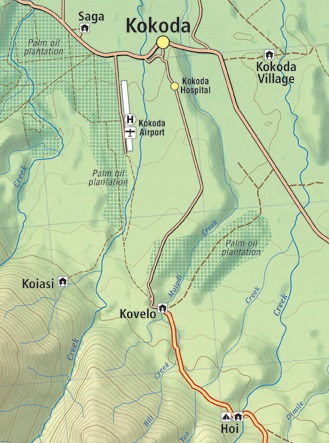

Day 11: Hoi Village Camp to Kokoda via Kovello – Charter flight to Port Moresby

Distance: 8.4 kilometres – Climb: 71 metres – Descent: 212 metres

A pre-dawn cuppa before our final leg and traditional welcome at Kokoda.

Kokoda at 395 meters AMSL is an Orokaiva village located on Madi Creek. The traditional word ‘Kokoda’ refers to ‘a place of skulls’ – ‘koko’ means skull, ‘da’ means village.

In November 1899, an expedition comprising Matt Crowe, Sam McLelland, and Archibald Lyon Walker, followed Clunas’ track into the valley and reached a barricaded village where they attempted to buy food. The occupants of this village, which was later to be the site of the town of Kokoda, attacked the expedition, killing two carriers.[i]

Kokoda is now a sacred heritage site for Australia. It was here that a small band of troops from the gallant 39th battalion first encountered the advancing Yokoyama Advance Guard before they were forced back into the jungle on the 29th July 1942.

You will inspect the position where a lone company of the 39th Militia Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Owen, prepared a defensive position to stop the Japanese advance. The average age of one of the sections of this band of Braveheart’s was 18½ years. They stood little chance against the confident and elite Japanese force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto Hatsuo. The Tsukamoto battalion of 900 combat infantry troops had landed at Gona on 22 July 1942 and immediately commenced their march towards Kokoda as the advance guard of the Nankai Shitai. Their full invasion force of 10,000 was scheduled to land at Gona in mid-August.

After some initial contact forward of Kokoda the Australian 39th Battalion consolidated their position around the edge of the escarpment … and waited!

Your trek leader will provide you with a full account of the battle which resulted in Colonel Owen being mortally wounded as he led the battle from the front with his young troops.

Lieutenant Garland:

‘He (Owen) was a fine man. He formed us up around the perimeter of Kokoda because that was where the Japanese would attack … and he walked around the top of the perimeter where we were all lying down … And I said ‘Sir’ I think you are taking an unnecessary risk walking around among the troops like that’. ‘Well’, he said ‘I’ve got to do it.’ I suppose a half hour later he got shot right through the forehead.’

Three months later, on 3rd November 1942 our ragged troops stood before General ‘Bloody’ George Vasey as the Australian flag was raised after one of the most epic campaigns in Australian military history.

Today four monuments stand as silent witness to these historic events. Your trek leader will provide you with a detailed briefing on the plateau and guide you to the Kienzle museum.

Kokoda is a substantial village with a couple of trade stores, a hospital (which does not have a doctor and only the most basic of medical supplies), a post office with a landline telephone which only works on rare occasions, a police station, a primary school, a VHF radio and an airfield. Kokoda is now on the PNG mobile network (Telikom and Digicel) and allows for global roaming.

After a hearty breakfast you will get to inspect the monuments on the plateau and the local Kienzle museum before moving down to the airfield to prepare for your charter flight back to Port Moresby.

We then board our bus for a visit to Bomana War Cemetery where we pay our respects to those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom during the Kokoda campaign.

have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.

King George V, Flanders, 1922

Final briefing at the Bomana War Cemetery

Bomana is the largest Australian war cemetery in the Pacific with 3823 graves. The cemetery lies in a serene tropical garden 19 kilometres north of Port Moresby off Pilgrims’ Way. The cemetery was begun by the army in 1942 and formally dedicated by the Governor-General of Australia, Field Marshall Sir William Slim, on 19 October 1953. Those who died fighting in Papua and Bougainville are buried here.

The Cross of Sacrifice, Memorial to the Missing and the Stone of Remembrance are built of a particularly beautiful golden-coloured sandstone. The graves are marked with polished marble headstones and dressed in uniform rows on sloping lawns between the Stone of Remembrance and the Cross of Sacrifice.

On a rise at the rear of the cemetery is the Port Moresby Memorial to the Missing which consists of a rotunda of cylindrical pillars enclosing a circle of square pillars with bronze panels engraved with the names of 703 Australians as well as Papua and New Guinea local forces listed as missing-in-action. The names of the battlefields on which the men died are carved on the entablature above the pillars. In the centre is a topograph with a bronze compass showing the direction and distance of the battlefields.

Here you will visit the resting place of the men who saved Australia including:

- Private Bruce Kingsbury VC of 9 Platoon, A Company 2/14th Battalion who was awarded the first Victoria Cross on Australian territory after a courageous solo effort to save his company by fearlessly cutting a path through the Japanese firing his Bren from the hip,

- Corporal Charlie McCallum of 12 Platoon, B Company 2/14th Battalion killed on Brigade Hill. Former Victorian Woodchop Chamion. Recommended for the Victoria Cross at Isurava for provided covering fire with his machine gun and refusing to leave until all his mates could escape even though he had been shot three times.

- Captain Claude Nye of B company 2/14th Battalion who was killed leading a courageous charge to save his Brigade Headquarters on Brigade Hill

- Capt “Lefty” Langridge of D Company 2/16th Battalion. Killed in the same action as Captain Nye in the Battle for Brigade Hill. Only six of the 78 men led by Langridge and Nye survived in their attempt to save their Brigade Headquarters.

- Lieutenant Colonel Bill Owen, Commanding Officer of the 39th Battalion. Killed while leading his troops from the front during the first attack on Kokoda.

- Corporal John Metson of the 2/14th Battalion. Refused to be carried on a stretcher after having been shot through both ankles wrapped them in field dressings and crawled on his hands and knees for three weeks. Left in the safe care of Sangai village by Captain Buckler who went ahead to seek help but betrayed by the villagers and bayoneted to death by the Japanese.

- Corporal Tom Fletcher of B Company 2/14th Battalion. A Medical orderly was a part of Captain Bucklers group who volunteered to stay behind with the wounded at Sangai including Corporatl Metson , they were betrayed to the Japanese and bayoneted to death.

- Lieutenant ‘Butch’ Bisset of 10 Platoon , B company 2/14th Battalion who died in his Brother Stan’s arms after the battle at Isurava, Butch had been machine gunned while leading his men in an attack against all the odds

along with 3815 young Australians who ‘gave their tomorrow for our today’.

“We think of them in sorrow and with pride, but there should be a third feeling stronger than grief, greater than pride. A sense of fullness and achievement. To us, their lives may seem to have been severely shortened. Yet in truth they were full lives. It is not how many years a man lives that matters but what he does with the years – many or few – that are granted to him. And those who sleep here did much with theirs”

Sir William Slim

After the commemoration service conducted by your trek leader we then return to our accommodation where you will be able to have a hot shower, a cold beer and an unforgettable pizza and later that evening a presentation dinner.

Day 12: Depart Port Moresby according to your individual flight itineraries

After breakfast we board the bus for a visit to the Orchid Gardens where we can view birds of paradise. We then drive via the Port Moresby harbour and CBD to give you a picture of the area before we go to the airport for check-in prior to departure.