The ‘blackbirding curse’ is as damaging to Papua New Guinea’s adventure tourism industry as the ‘resource curse’ is to mining and exploration.

‘Blackbirding’ was a term given to the coercion of native people from Papua New Guinea to work as cheap labour in Queensland’s sugar plantations in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When the extent of the exploitation became known it was outlawed as a form of slavery.

The ‘resource curse’ refers to the paradox that countries with an abundance of natural resources tend to have less economic growth, less democracy, and worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources.

Over the past decade 45,000 Australians from all walks of life have trekked across the Kokoda Trail. Their reasons are many and varied but the wartime significance combined with a sense of adventure in the land of the unexpected is the most compelling motivation.

Kokoda has now surpassed Gallipoli as a priority bucket list item.

Prospective trekkers become self-absorbed as they research trekking companies, camping gear, training methods and the wartime history of the campaign.

They learn of the loyal sacrifice of ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’ – those legendary wartime carriers who supported our troops and they look forward to sharing the experience with their descendants who will be employed to get them safely across the trail.

They expect these young guides and carriers will be properly cared for by the trekking company they engage to complete their trek. They expect that government will do its job and put in place rules and regulations to protect them against exploitation. They expect Australia will ensure the wartime history of the Kokoda campaign will be protected. They expect that local subsistence villagers will receive their fair share of benefits from the emerging trekking industry.

Unfortunately, the failure of government to manage these expectations has created a laissez faire market where the caveat emptor of ‘let the buyer beware’ prevails.

Since the Australian government assumed control of Kokoda a decade ago, they have invested more than $50 million of taxpayer’s funds in what is euphemistically called the ‘Kokoda Initiative’. The results are not good.

Trekker numbers have declined by 42 per cent under their watch. Not one of the five strategies or 33 key performance objectives established in their Strategic Plan for the Kokoda Trail from 2012-2015 was achieved.

Over this period there has been ongoing environmental degradation along the trail; areas with significant wartime heritage values have been desecrated; sections of the trail are dangerously unsafe; there are no toilets that meet the most basic of hygiene standards; there is not a single management protocol in place; no audited financial reports have been published by the management authority for at least five years; no newsletters have been produced; and no funds have been distributed to local communities.

The management authority does not have a database. There is no trek itinerary management system. It is not possible to book a campsite. The ranger system has collapsed. Local guides and carriers are shamelessly exploited by being overloaded, underpaid and poorly equipped – one collapsed and died on the trail last year.

Of greater concern however is the lack of any Government commitment towards the protection of sites sacred to our shared military heritage along the Kokoda Trail. After a decade in situ there is still no master plan to honour and interpret the Kokoda campaign for future generations.

The only beneficiaries from the $50 million plus we have invested over the past decade are government officials and the consultants they have engaged for esoteric studies relating to climate change, gender equity, capacity building, social mapping, mentoring, village livelihoods and any other fashionable causes that excite progressive Canberra based bureaucrats.

The recent collapse of the management system put in place by these officials and their consultants has led to Prime Minister Peter O’Neill calling for an urgent review. We should be embarrassed that it has come to this.

The dysfunction has spawned a new breed of blackbirders within the Kokoda trekking industry. Anybody can be a trek operator for a token fee. There is no due diligence check to see if they have a registered company with appropriate insurances, training, experience and emergency gear. There are no rules.

All a Kokoda blackbirder needs today is a plagiarised website and they are in business.

The onus therefore lies with prospective trekkers to ensure they do their research to ensure they are not unwitting exploiters of the local porters who will sacrifice their all to get them safely across the trail.

The unwitting supporters of the blackbirders are those who go for the cheapest option with the trek operator they choose. They are usually so engrossed with their own their own egos they neglect to check if their blackbirder limits the weight of backpacks to 18 kilograms for their porters which was the maximum allowable weight imposed by the Australian army during the Kokoda campaign in 1942.

They are so concerned with their own comforts they forget to check if their blackbirder issues each of their PNG support crew with a sleeping bag as temperatures drop to near freezing in the upper reaches of the Owen Stanley Ranges – and a suitable mat to protect them from the wet ground they have to sleep on.

There are many other issues to check to avoid supporting a blackbirder. The quantity and quality of the rations for their porters – their rates of pay – their ‘walk-home’ allowance – their trek uniforms – their medical support. These are not important issues for blackbirders but they should be vital to any trekker with a conscience.

An apathetic government that failed to take a single Kokoda veteran to PNG for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Kokoda campaign – or send a single MP to represent the Prime Minister at the Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery this year – cannot be relied on to protect the descendants of those who did so much to protect our troops in 1942.

Further Reading:

- Envirocrats Hijack Kokoda

- Kokoda Tour Operators Association – A Shameless Australian Lobby Group

- An Open Letter to Mrs Sue Fitcher – President of the Kokoda Tour Operator Association

- Mick O’Malley – Kokoda Powerbroker!

- Kokoda Spirit Review – Let the Buyer Beware

- David Howell – Kokoda Charlatan!

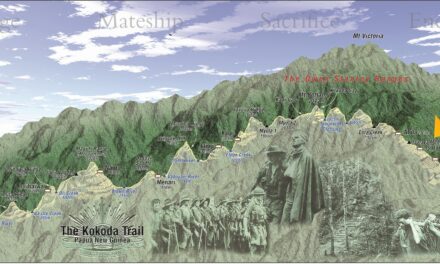

Illustration: Charlie Lynn.