In early 1991 a couple of Papua New Guineans, Bernard and David Choulai, hatched a plan to organise a race across the Kokoda Trail to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign. They discussed the idea with a friend and former kiap, Stuart Armstrong who explored it with his mate, television sports presenter, Patrick Lindsay.

Patrick had previously covered the annual Sydney to Melbourne ultramarathon I used to organize for Westfield. He was also aware that I had served in the army for 21 years and held the NSW 24-hour ultramarathon in 1987,

I was excited at the prospect of bearing witness to the stories I had read and heard from my father who served as an infantryman in New Guinea and about Kokoda. Ever since I was a boy the memory of thousands of our veterans marching behind battle honours emblazoned with names such as Kokoda, Deniki, Isurava, Templeton’s Crossing and Eora Creek was etched in my mind.

I was excited at the prospect of exploring the Kokoda Trail bur disappointed to learn there was such little information about the conditions of the Trail itself – no reliable maps no information on the Trail itself.

I was keen to see the remnants of the steps up the infamous ‘golden staircase’; to feel the pain of climbing ‘Engineers Ridge; to wonder how our diggers felt in their weapon pits on the forward slopes of ‘Brigade Hill’ as they waited to meet the enemy; to follow the footsteps of Private Bruce Kingsbury as he led a counter attack against the Japs at Isurava; to stand on the ground defended by Charlie McCallum as he bravely stood between the Japs and his men to protect their escape.

I wanted to see where Captain Butch Bissett was machine gunned; where Ben Buckler led his fateful patrol; where Captains Claude Nye and Brett Langridge led their heroic charge at Brigade Hill; where Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Honner held his famous parade at Menari with ‘Those Ragged Bloody Heroes’ of the 39th Battalion; where Corporal John Metson and Sergeant Lindsay Bear crawled on all fours along the trail refusing all offers for help because they had mates ‘a lot worse off than us’!

Port Moresby Circa 1991

Arriving at the old Jackson’s airport in 1991 was a bit of a shock. I was met by Bernard Choulai who drove me to his haus in Badili near the Koki markets in Port Moresby. Every haus along the way was surrounded by razor wire and there seemed to be an armed guard at every entrance. Potholed roads and decrepit buildings were stained red with blobs of betel nut spit. The streets were littered with rubbish which was disposed of by the lighting of small fires every few hundred metres.

This forbidding first impression was quickly subdued by the uninhibited friendliness of the people. I was warmly welcomed by everybody I met and quickly felt at ease in the place.

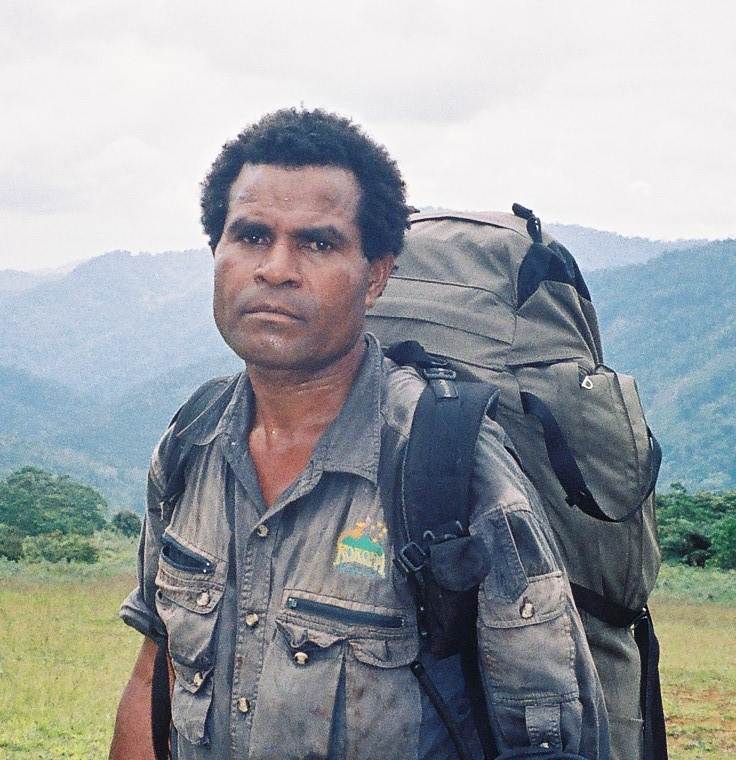

Alex Rama – Kokoda Guide

Bernard introduced me to the guide who would lead me across the trail. His name was Alex Rama, a Mountain Koiari from Naduri village on the trail. I couldn’t get much out of Alex – his English was poor and my Pidgin was non-existent so I felt we were in for some interesting days ahead.

A lack of information and maps meant I had to overcompensate with rations and gear. All I could get from Alex when I asked him how long it would take us to get to Kokoda was ‘maybe a week – maybe longer! I assumed he was going to see how I coped in the wet with my old army A-frame backpack that weighed in at 35 kg before he would give me a more accurate estimate.

The next five days were the wettest and toughest I can remember. The trail itself was not marked or even visible in many areas. Alex often stopped to scan the area before committing to where we should go. I later read where a British trekker got lost in the area between Imita and Ioribaiwa ridges which extends for five kilometres and crosses Emoo and Matama creeks 22 times. He was lucky to be found – and very lucky to survive.

We pushed on till dark each day when I rigged up my old army hutchie to sleep under. The constant rain had increased the weight of my pack and caused my skin to chafe. The hills never seemed to end. After a couple of days, I stopped asking Alex how far to go wherever we were going because the answer was always the same – ‘about 25 minutes’ he would say without changing his facial expression or giving any further hints.

We had our first disagreement on direction at Efogi. My sketch map indicated we should continue directly north to Kagi village but Alex became animated for the first time and indicated we should take another trek to the North-East. There were no villages in that direction on my sketch map but it was apparent that was his preferred route so I slung my backpack across some very sore shoulders and followed him.

Naduri Village

Hours later we entered a misty village perched on a mountain spur towards the top of Tovovo Ridge. Alex was obviously well known to the villagers and soon disappeared with a number of them. All I could do was pull out my ration pack and hexamine stove to make a brew. I soon noticed that villagers had formed a semi-circle about 30 meters away – it was apparent they were carefully observing what I was doing as they sat in silence and stared.

Whenever I looked down at my stove to check my brew I noticed very young children tip-toeing towards me to have a closer look. Whenever I looked up, they would giggle and rush back to the safety of their elders in the semi-circle. This became a ritual until Alex appeared about half-an-hour later. He told me this was his village which was called Naduri and he had gone to see his parents.

Later in the afternoon a villager with a machete and shoulder satchel approached me and introduced himself as ‘Mark’. He asked that I follow him. I asked him where we were going. ‘Myola’ he said. How long will it take? I asked. ‘About an hour’ was his response before turning and heading off up the mountain in the mist. I didn’t seek him against until about three hours later when the jungle cleared to reveal an expansive grass covered plan. It was a remarkable contrast to the jungle canopy that had enveloped us since we left Owers Corner. I later learned that the two dry lakebeds referred by locals as ‘big Myola’ and ‘little Myola’ were extinct volcanic plateaus. I also learned they are anything but dry – swampy and marshy would be more appropriate terms.

Lake Myola

The lake beds are such a contrast to the surrounding jungle which extends as far as the eye can see – and beyond – that the local Koiari tribes regarded them as ‘tabu’ land. As I gazed across the area, I felt a distant familiarity with are area but was too tired and physically sore to think too deeply about it.

Alex had lingered in his village for a while and caught up with me at the edge of the lake. Mark was not to be seen but the smoke coming from the hut in the distance indicated he had already arrived at the guesthaus. We joined him over an hour later after some heavy going through the swamp.

I settled into my hut which had a fire on top of soil to stop it burning through the floor. The soil was surrounded by small rocks to keep it in place – crude but effective and very welcoming. We were at 2200 m AMSL and temperatures can drop to near zero in the area. We rigged up a line to dry our clothes but the most painful part of the operation was lifting by arms above my shoulder to hang them due to the soreness in my shoulders.

Next morning Mark surprised us with some fresh bread he had baked – my first piece of toast since we started. It was the beginning of a long relationship with Mark and his guesthaus.

After breakfast Mark presented me with Visitor’s Book to sign. As I perused it, I noted that previous guests had commented on a plane they had visited. I asked Mark where it was and he explained that ‘long time ago Mixmaster come from Jesus and carried it away’.

This helped explain my distant familiarity with the area.

Myola Flashback

In 1979 I had returned from a two-year posting with the US Army Parachute Rigging School in Fort Lee, Virginia. On my return I was promoted to Major and posted to the RAAF Base at Richmond. One of our specialities was rigging underslung loads for helicopters. We received an order to fly to Papua New Guinea to recover a Talair aircraft that had crashed in the highlands. We had a chinook helicopter and about half-a-dozen riggers. After recovering the aircraft to Goroka we were tasked to lift an old warplane somewhere East of Goroka and recover it to Port Moresby for restoration.

I recall the chinook shutting down its engines and we alighted in what we all felt was an eerie scene – remote, isolated and deathly quiet. We had landed beside an old Ford Trimotor which had crashed in the area during the Kokoda campaign, recovered it to Port Moresby then returned to Australia. Mission accomplished.

On my return to Australia after the trek I checked my army records and the place we lifted it from 12 years earlier was Lake Myola!

Alex and I resumed our trek back across the lakebed. The terrain had changed into Moss Forest and the walking was not as difficult for the next couple of days.

Adrenalin Rush at Eora Creek –

Our next obstacle was Eora Creek. The rain had not let up and it was thundering whitewater. The log bridge had been swept away and our only chance of getting across was with the rope we had with us. Alex gestured that he would try and find a crossing point downstream. He then disappeared for a couple of hours. All I could do was make another cup of tea and rest.

Alex eventually emerged from the bush and led me through a path he had cut. We reached the edge of the water then took it in turns to cut a tree to drop it on a group of large boulders about a third of the way across. We then shimmered backwards down the trek and took a break. Alex then secured a rope to the boulders and entered the raging creek which was about waist deep. I was amazed at his strength and his poise as he edged his way to the next group of boulders unfurling the rope as he progressed. He then held the rope which allowed me to edge across and grab his outstretched hand as he hauled me out.

Alex then went back to recover the rope and do it all again.

We took a long break as we examined the next obstacle which was about a 2 meter gap to a boulder on the edge of the other side. Alex eventually removed his boots and stood rocking back and forth before launching himself into the air and landing on the rock – it was as if his feet had suction cups underneath them. He looked back at me with a huge grin – the first sign of emotion he had displayed since we started.

I threw the rope across to him to secure on the other side then had to drop into the water-gap which was shoulder deep. The pressure of the water against my backpack was incredibly powerful. I looked up at Alex – I could see the concern on his face but my focus was on my inch-by-inch progress until I could reach Alex’s outstretched hand. It was the second time he grinned that day.

We continued our trek up to Alola village where we were warmly welcomed once again. I later learned that Alex was telling the villagers that I would be bringing many trekkers across later on.

Kokoda

A day out of Kokoda and I was in a lot of pain. My skin was pulpy from the constant wet – my shoulders had welts in them from the backpack and my toes were stuck together. I didn’t have much left in the tank.

During the final few hours, I started to fantasise about a hot bath in Kokoda – I had been told it was the biggest village across the trail and was the catchment area for a couple of thousand Orokaiva. I assume it had at least one hotel. My vision of a big steak and hot bath were soon shattered – the only luxury was an old building with a septic tank and a wash basin on the Kokoda Plateau.

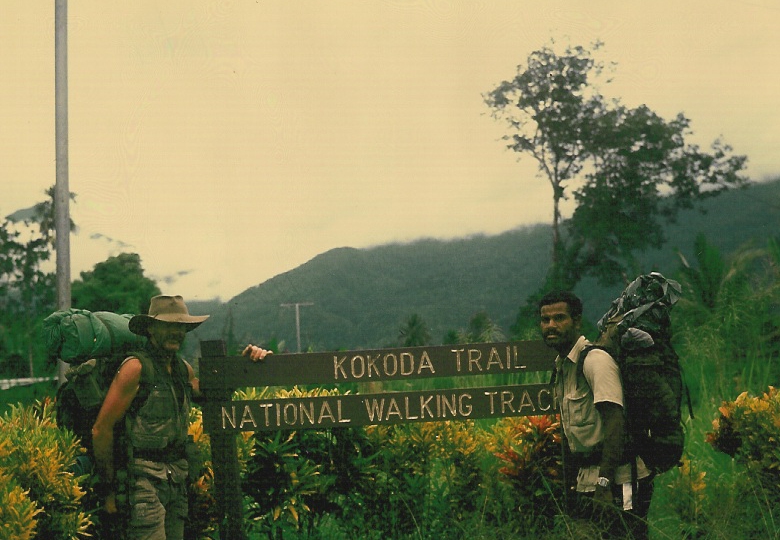

I was met by Pastrick Lindsay who conducted an interview on our plan for a race across the Trail after I had slumped onto one of the old monuments on the Kokoda plateau – it was about as raw as it gets: THE KOKODA EPIC RUN!

The Result

Back in Sydney we developed a sponsorship proposal and I began marketing the idea of our proposed ‘Epic Run’ however it soon became clear ‘Kokoda’ was a distant concept to the younger generation 50 years on from the war and did not have any resonance with them. Some thought I was talking about ‘Kakadu’!

This was a disappointing shock to a wartime ‘baby-boomer‘ from that era!

I also found that I was unable to explain the experience. It was akin to explaining life as a soldier – if you’ve never worn the uniform you will never understand!

I therefore resolved to organise a commemorative trek across the Trail and subsequently led my first group into the 50th anniversary Anzac Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery on Anzac Day, 1992.

The national ‘Bulletin with Newsweek’ magazine joined the historic trek and ran a feature article titled : ‘A Walk on the Wild Side’.

We have since been followed by more thatn 56,000 Austrtalians who have committed to what is now a unique Australian pilgrimage which has rekindled our relationship with Papua New Guinea and the traditional custodians of land sacred to our shared military heritage.

Kokoda tourism now offers them a hope for a sustainable economic future based on Kokoda pilgrimage tourism – and Alex Rama should be remembered as one of PNGs proudest pioneers in this regard,

Charlie Lynn and Alex Rama at Kokoda – 1991

Postscript

I went onto develop a strong mateship with Alex Rama who was my chief guide for all the treks we led over the following 15 years. Sadly Alex passed away in 2015 after a short illness however he will never be forgotten for his leadership during those pioneering years.