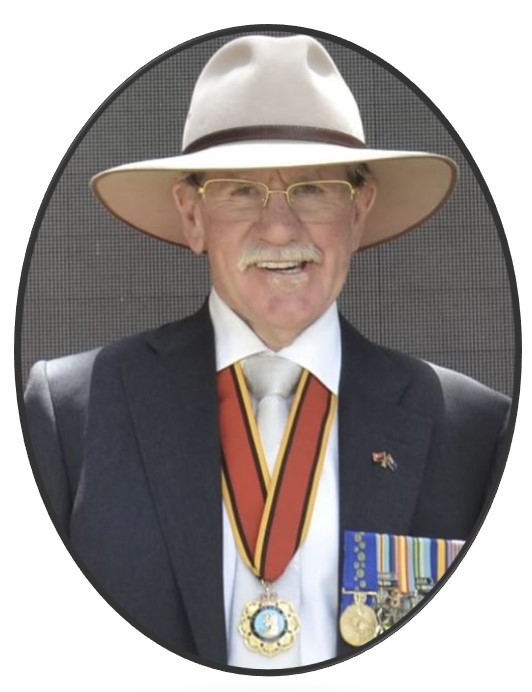

Submission to the Australian Senate by The Hon Charlie Lynn MLC, 10 March 2006

Preamble

I first went to Papua New Guinea in 1979 on a mission with the Australian Army. Since 1991 I have been leading groups across the Kokoda Trail and have established a Foundation to have the track proclaimed as a National Memorial Park. We are working with the World-Wide Fund for Nature in Papua New Guinea, the University of Technology Sydney, the PNG Tourism Promotion Authority and the Kokoda Track Authority to develop a model of sustainable tourism for Papua New Guinea.

As a Member of the New South Wales Parliament, I have elected to use my Commonwealth Parliamentary Association research entitlement on our relationship with Papua New Guinea. I have travelled to Port Moresby, Goroka, Lae and Madang as part of my research and have held numerous meetings with Ministers, Members, Departmental Secretaries, Provincial and Local Level Government representatives and numerous clan leaders and landowners.

There is no doubt that we have made serious mistakes in our relationship with Papua New Guinea since independence in 1975. There is also no doubt they are a very difficult people to ‘help’ given the complexities of their ‘wan tok’ system and their adherence to ‘the Melanesian way’.

I doubt that we will ever understand these complexities and we certainly will not solve them in our lifetime. What we can do however is to begin to workshop ideas that allow us to better understand each other; to develop pilot programs based on educational-economic partnerships; to develop political partnerships to administer our aid budgets and to develop long term leadership programs for leaders yet to be born.

‘Given the youth bulge in most island nations, the issue of employment generation will become increasingly urgent in the Pacific in coming decades, and there is growing discussion about the potential to address it through greater international labour mobility.

‘The pressing need to find jobs for Pacific Island workers coincides with the emergence of gaps in the labour force of developed nations. In countries like Australia, lower birth rates, the ageing demographic profile, increased personal wealth, the provision of social welfare, sustained economic growth, low unemployment and higher levels of education have combined to reduce the supply of workers who are available (or willing) to undertake physically demanding labour for relatively low pay. This has opened up the debate about the potential for temporary employment schemes for Pacific Islanders to work in overseas labour markets, particularly in seasonal pursuits in agriculture.’[i]

Senate Inquiry

The Senate inquiry into seasonal labour from the Pacific Region is a welcome initiative however the terms of reference seem to be limited because they do not address the impact of labour mobility on our relationship with our Melanesian neighbours in the Pacific Region. These nations comprising the island chain from Timor in the northwest through West Papua, Papua New Guinea, Nauru, Vanuatu, Kiribati, the Solomons and Fiji have been referred to as our arc of instability.

It is certainly our international area of responsibility.

Recent reports from the Centre of Independent Studies, the Menzies Research Centre and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute have traced our historical ties with each of these nation states and the impact of our withdrawal from anything smacking of neo-colonialism in the 1970s. More ominously they have highlighted the failure of our aid policies over the decades since they were granted independence from their colonial administrators.

Those with expertise in the region warn of catastrophic consequences for Australia and the island nation states if the impending crisis is not arrested. This realization has led to our direct intervention in Timor and The Solomons, a change in our aid policy from a ‘magic pudding’ concept to a ‘tied-aid’ policy formula, a more forthright role in the Pacific Forum, and the implementation of an Enhanced Cooperation Program (ECP) for Papua New Guinea.

Our relationship with Papua New Guinea is particularly important given our historical links as a colonial administrator, wartime ally, fellow Commonwealth member and closest neighbour. More recently the threat of terrorism, the sharing of a border with Indonesia, the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, crime and widespread corruption has led to many commentators issuing dire warnings about its future.

The ECP program has been implemented in response to these concerns but many of the problems are now so entrenched that the Australian Strategic Policy Institute argues the program should be regarded as only the first phase of a process that will take generations to resolve. Former Prime Minister, The Rt Hon Sir Mekere Morauta, Kt MP expressed a word of caution in his response to the Australian Security Policy Institute report:

“I am worried that the Enhanced Cooperation Program is too much at once, and expensive for what it might achieve. What is critical for any measure of success is for Papua New Guinean officials to be deeply involved in it and for people to see tangible accomplishments soon.”[ii]

This is a prescient warning for Australia in considering the value of any programs under this initiative.

Each of the reports from the Centre of Independent Studies, the Menzies Research Centre and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute has made a significant contribution to the debate about the significance of our relationship with PNG and our international responsibility as a leader in the region.

Apathy or Empathy?

In my view there is a growing empathetic gap between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Up till independence in 1975 Australia had an active patrol officer/kiap program involving young men working throughout Papua New Guinea under our colonial administration. Many of them stayed on after independence, married and became PNG citizens. They developed a good understanding of the complexities of Melanesian culture and are much more understanding of their ways and their needs. At the same time students from Papua New Guinea came to Australia to complete their tertiary education and came to better understanding the complexities of our western culture.

The Australian ‘kiaps’ are now approaching retirement and Papua New Guinea now has its own university. We do not have any exchange programs where young leaders from either country can develop a proper understanding of each other. Our corporate knowledge is therefore diminishing and our empathetic gap is widening.

This gap is reflected in our attitude to the administration of aid. Here in Australia we often beat ourselves on the chest with announcements of how much we provide in aid each year. In Papua New Guinea they are more circumspect as they realise that most of the aid money ‘boomerangs’ back to Australia. Sean Dorney’s description of a two- day forum regarding our change in policy to ‘project’ or ‘program’ aid in Brisbane in 1993 is instructive:

‘This switch was explained to 400 hungry-eyed Australian consultants and representatives of various NGOs all with ideas on how to get in on the action. A year or two prior to this, Australian aid officials had set up ‘joint’ committees covering the agreed sectors into which Australian money could be channelled – health, education, infrastructure, renewable resources, law and order, and the private sector. The chairman of the Sectoral Working Groups presented their reports on what was planned in their area of expertise. It was stunning just how much basic policy on fundamental issues, such as the future of education and health in PNG, had been appropriated by these committees. Admittedly they did have PNG representation but given the shortage of skills in the PNG bureaucracy and the multiple demands on talented manpower it was inevitable the Australian ‘experts’ dominated, working under the imperatives of deadlines set by the Australian aid authorities.

‘Sir Julius Chan, who was Finance Minister at the time, told me during the forum that it was “a very cumbersome, very tedious, very unnecessary load of work”. Australia’s then Development Cooperation Minister, Gordon Bilney, put the alternative argument. He asked whether the untied aid arrangement agreed to at independence out of “respect” for PNG’s sovereignty might have been the wrong decision. “Would it have been better.” Bilney said, “[for Australia] to have remained engaged in some way? Would it have been better to use Australia’s more developed technical and human resources to work together with Papua New Guinea to develop their country? Would that have ensured more rapid and more equitable development?” Chan’s answer was a flat no. “We are concerned,” Sir Julius told the forum, “that the decreasing real value of support could lead to be of less and less tangible benefit if it is frittered away on too many programs and projects which have excessive bureaucratic and administrative costs. “He was particularly concerned about the rake-off to consultants. The then Secretary of the PNG Prime Minister’s Department, Brown Bai, after hearing the presentations by the Australian chairman, expressed surprise at the amount of work the teams had done planning PNG’s future. “I am supposed to be the PNG Government’s chief adviser,” he said, “but I know nothing about this.”

Many MPs in the National Parliament are critical of this approach. AusAID is seen as a law unto itself and do not have to report to, or liaise with, local Members when undertaking project work in their electorates. This causes them embarrassment when their constituents advise them of the work being undertaken and undermines their status in the eyes of their people. According to Sean Dorney:

‘There is a terrible temptation facing Australians who work on these aid projects to push the Papua New Guineans aside and take over the problem to effect a quicker result. But it is self-defeating.’

The root cause of this attitude can be traced to a Committee established in the 1960s by the Australian External Territories Minister, CEB Barnes. According to Professor Donald Denoon in his recently published book on Australia’s decolonisation of Papua New Guinea, called A Trial Separation, he wrote: ‘Western behaviour was the goal, indigenous values the obstacle and paternal administration the solution.’

A review of our aid programs would indicate that not much has changed over the 45 years since Minister CEB Barnes established that committee.

White Australia – Black Melanesia!

Melanesia is a Greek term for ‘Black Islands’.

During a meeting with a senior Minister in the current PNG Government in Port Moresby I asked how Papua New Guineans were treated whenever they applied for a visa to come to Australia. ‘Like lepers!’ was the candid response.

This issue is one that bites deepest in our relationships with PNG. Over the years I have heard Australians complain of their ‘treatment’ when they arrive in Britain as visitors. They claim there seems to be no special recognition for us as a former colony, wartime ally, trading partner and fellow Commonwealth member. Many of those aggrieved by this treatment have become vocal proponents of the call for an Australian republic.

So it is with PNG. Many see Australians as disinterested visitors who travel to PNG, participate in meetings, join a conducted tour, perhaps visit a village, offer some patronizing advice – then leave! A review of the number of times Australian politicians have chosen PNG as a destination for their overseas study trips over the past decade would be a good indicator of our dinkum level of interest in the country.

Australia has reciprocal arrangements for working holiday visas with Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Eire, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. But none with PNG!

As a Commonwealth nation, young people from PNG are eligible for working holiday visas in the United Kingdom under the Commonwealth Working Holiday Scheme – but not in Australia!

When an Australian travels to PNG for a visit they stand in a line at Port Moresby airport, get their passport stamped and immediately obtain a visa.

When a PNG citizen applies for a visa they have to fill out a comprehensive application form, provide bank guarantees and detailed itineraries. If they live outside Port Moresby (as 87 per cent of the population do) it becomes even more complex and can involve multiple trips from remote mountain villages to the Australian embassy in Port Moresby due to acts of bureaucratic bastardry.

There are no exceptions – a current Member of the PNG National Parliament who is a former Australian citizen and decorated Vietnam War hero is given the same treatment. Another former Australian citizen who was conscripted into the army in 1968 and sent to PNG as a National Serviceman returned as a teacher. After independence he became a PNG citizen and has made an outstanding contribution in his field. Unfortunately he has had to forfeit his rights to an Australian pension and other benefits such as health care – and he is treated as an alien whenever he decides to visit his family in Australia.

All native PNG people and former Australian citizens find this to be a humiliating and traumatic experience. One told me of a talented young PNG artist who was invited to come to Australia but was afraid to go through the process of obtaining another visa because he was so traumatised by a previous application.

On January 30, 2005 the Sydney Sun-Herald reported that the shortage of seasonal labour for fruit and vegetable picking was so chronic that the Sunraysia Mallee Economic Development Board is planning to import 10,000 Chinese temporary workers. Eighty-five percent of PNG citizens live in rural areas on a subsistence basis. They have been harvesting fruit and vegetables for generations over thousands of years.

In 1930 the Australian Government Anthropologist, F.E. Williams wrote of the Koiari:[iii]

‘the Koiari are very definitely gardeners and quite dependent on the soil . . . they are given a good character by employers as honest labourers and pleasant men to work with. . .’

Twelve years after Williams wrote his report on ‘The Bush Koiari’, they were called to our aid in one of the most desperate chapters in our history – the Japanese invasion of Australian mandated territory in New Guinea. They answered the call and worked tirelessly under atrocious wartime conditions to carry vital supplies to our endangered troops and then saved numerous lives by carrying our wounded back to safety. They were immortalised as ‘fuzzy wuzzy angels’ and without their assistance we would have been defeated by the Japanese on the Kokoda Trail. To our eternal shame they have never received a medal for their heroic sacrifice on our behalf – and today they are not even regarded as worthy to pick our fruit or harvest our vegetables.

And we wonder why they feel we neither care nor understand them!

It is interesting that the Australian Strategic Policy Institute regards PNG as ‘one of our three top policy challenges’. If this is the case then those responsible for formulating and implementing policy need to change their itineraries for overseas travel post-haste!

Graeme Dobell, in an address to the Menzies Research Centre, refers to the issue of a special migration status for PNG citizens as the great taboo.

‘Over the past four decades, we have gone from the White Australia policy to a universal, non-discriminatory policy. And at no point in that huge shift has there ever been a moment when Australia opened its doors to the Islanders. Australia has unintentionally sub-contracted its Pacific people policy to New Zealand. Polynesians have the right to go into New Zealand and from there to Australia. Melanesians have no such avenue. What that means is that you are much more likely to see a Polynesian face on the streets of Sydney or Melbourne than a Melanesian face.’[iv]

The issue has been addressed by the 1984 review of overseas aid, the Jackson Report[v], and the 1997 Simons report[vi] but the findings and recommendations were largely ignored. More recently submissions to a Senate inquiry on relations with the Pacific ‘were surprisingly sensitive to this ‘no-go’ area – most not even mentioning it.’[vii]

The Australian Council for Overseas Aid came down with a non-committal bureaucratic conclusion:

‘The issue of job opportunities for Pacific Islanders in Australia is a complex and sensitive one but the pros and cons of the issue need to be considered.’[viii]

Australia has to come to terms with the reality that our immigration policy is racially biased against Melanesians – the very people we have an international responsibility to help and assist.

The Centre for Independent Studies reported that ‘the problems of Papua New Guinea and its Melanesian neighbours do not divide up neatly between government departments’.[ix] The report noted that ‘Australia has an Iraq taskforce when it needs a Melanesian taskforce’.[x]

Labour Mobility in the Pacific[xi]

A research paper titled ‘Labour mobility in the Pacific: creating seasonal work programs in Australia’ and presented to the Globalisation, Governance and the Pacific Islands conference at the Australian National University (25 -27 October 2005) is deserving of special consideration by the Senate Committee. Authors Nic Maclellan and Peter Meares address the issues of remittances, pacific development, modelling of seasonal work schemes in Australia and the requirements for effective seasonal workers schemes.

The paper notes that ‘in its 2003 inquiry on Australia’s relations with the region, the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee received numerous submissions suggesting schemes to bring workers from the Pacific and recommended ‘a pilot program to allow for labour to be sourced from the region for seasonal work in Australia.’[xii] In its formal reply to the Senate report, the Australian government simply ‘noted’ the recommendations for a pilot study, adding a one line response: ‘Australia has traditionally not supported programs to bring low skilled seasonal workers to Australia’’[xiii]

Maclellan and Mares conclude that the obstacles to such a scheme are political and bureaucratic. I believe it reflects an appalling lack of understanding and empathy with Papua New Guinea; a lack of political will to address the issue and a deep seated racial bias against Papua New Guineans in the bowels of the Canberra bureaucracy.

The paper examines the political and bureaucratic objections to seasonal labour schemes and relates them to Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program and their experience with the issues concerning regulation, labour rights and social impacts which would have to be addressed in Australia if seasonal work schemes were to operate ‘without evoking memories of blackbirding’.

Village – Farm Relationships

One of the major concerns in Australia is the fear of seasonal workers overstaying their visa’s. This would be ameliorated by the development of a disciplined program in partnership with Papua New Guinea to ensure participants are carefully selected, medically screened and that they undergo some in-country pre-employment training. They should also be assisted in establishing a system to ensure there is a saving element with their remittances and that an appropriate amount is directed to their family.

A long-term strategy to develop partnerships between village areas in Papua New Guinea and farming communities in Australia would also have mutual benefits. If Papua New Guinea seasonal workers know they will be able to return the following year for work it will remove any incentive for them to overstay.

Training would also be an integral component in any such scheme. This would involve pre-embarkation training in Papua New Guinea and vocational/on-job training in Australia.

Conclusion

Australian policy makers cannot ignore the dire warnings in recent reports regarding our relationship with our Melanesian neighbours who form the ‘arc of instability’ to our immediate north. This is our international area of responsibility. We have to change our approach and seek to emulate the New Zealand way of treating our neighbours as ‘cousins’ rather than ‘little brothers’. An essential part of this change will be to demonstrate that we are going to deconstruct the racial bias we have against them and implement programs where we can help each other and better understand each other.

A first step in this process would be to establish a joint working group with Papua New Guinea in order to develop a pilot project for seasonal work in Australia.

I would hope this would be a strong recommendation of the Senate inquiry into seasonal labour from the Pacific region and that somebody within the government will give it more than a cursory glance.

THE HON CHARLIE LYNN MLC

[i] Labour mobility in the Pacific: creating seasonal work programs in Australia by Nic Maclellan and Peter Mares. Paper for conference on ‘Globalisation, Governance and the Pacific Islands. Australian National University, Canberra, 25-27 October 2005

[ii] Perspective: Papua New Guinea. Attachment to Australian Strategic Policy Institute Report: Strengthening our Neighbour: The future of Papua New Guinea. P54.

[iii] The Bush Koiari People of the Sogeri People. F.E. Williams. Government Anthropologist of the Territory of Papua

[iv] The Menzies Research Centre. Australian Security in the 21st Century Seminar Series. The South Pacific – Policy Taboos, Popular Amnesia and Political Failure. Graeme Dobell. P.19

[v] Jackson Report, Report of the Committee to Review the Australian Overseas Aid Program, AGPS, Canberra, 1984, p.181

[vi] Report of the Committee of Review on The Australian Overseas Aid Program, One Clear Objective: poverty reduction through sustainable development, chairman H.Paul Simons, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 1997, p.116

[vii] The Menzies Research Centre. Australian Security in the 21st Century Seminar Series. The South Pacific – Policy Taboos, Popular Amnesia and Political Failure. Graeme Dobell. P.20

[viii] Australian Council for Overseas Aid, Submission to Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee: Inquiry into Papua New Guinea and the Island States of the Southwest Pacific, Submission No. 37, 2002, p.35

[ix] The Centre for Independent Studies. Issue Analysis No 30 dated 12 March 20003. Papua New Guinea on the Brink by Susan Windybank and Mike Manning. P15

[x] Ibid. p15

[xi] Labour mobility in the Pacific: creating seasonal work programs in Australia. Research paper by Nic Maclellan and Peter Mares and presented to the ‘Globalisation, Governance and the Pacific Islands’ conference at the Australian National University, Canberra, 25-27 October 2005. Part of the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Project (SSGM)

[xii] Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee: ‘A Pacific Engaged – Australia’s relations with Papua New Guinea and the islands of the south west pacific (Canberra, August 2003) p76

[xiii] Government response to ‘A Pacific Engaged’ (Canberra, April 2005). This formal response to the August 2003 Senate report was dated 5 April 2005 but only issued on 24 June 2005, the day after Parliament broke for its winter recess.

I