Speech to the NSW Parliament re Aboriginal Reconciliation by The Hon Charlie Lynn MLC: 2-12-2003

The Hon. CHARLIE LYNN [10.27 p.m.]: As a direct descendant of Duncan and Nora McColl of Delegate, a few months ago I was invited to participate in a Wudiki ceremony in Darwin. This came about because in the early 1930s Constable Albert McColl was speared by an Aboriginal man of the Wirrapanda and Yolngu people called Dh’a’kiyarr.

There had been a report that the crew of a Japanese pearling lugger had been murdered by Aborigines in Arnhem Land and he was part of a police expedition sent out to investigate.

In the course of that investigation he was speared by Dh’a’kiyarr. Later, missionaries persuaded Dh’a’kiyarr to surrender himself, which he did. He was brought before the court in a case called the King v Tuckiar, found guilty and sentenced to death.

There was a huge outcry in the southern States and the High Court in Melbourne overturned the sentence. That was a special milestone in black-white relations.

The Federal Government then gazetted that no Aborigine could be put to death in Federal territory. After that the McColl clan felt aggrieved and that justice had not been done, because after he was released by the court Dh’a’kiyarr disappeared and was never seen again.

The Wirrapanda clan felt aggrieved because he had not returned. According to the Wudiki ceremony, when two tribes wrong each other the matter must be resolved. Aboriginal law dictates that the resolution is achieved through Makarrta, which is a ceremonial trial by ordeal. The offender is required to dance in front of the aggrieved while spears are thrown at him. If he survives, he then presents himself to be speared in the thigh, thus restoring honour and resolving the issue for good.

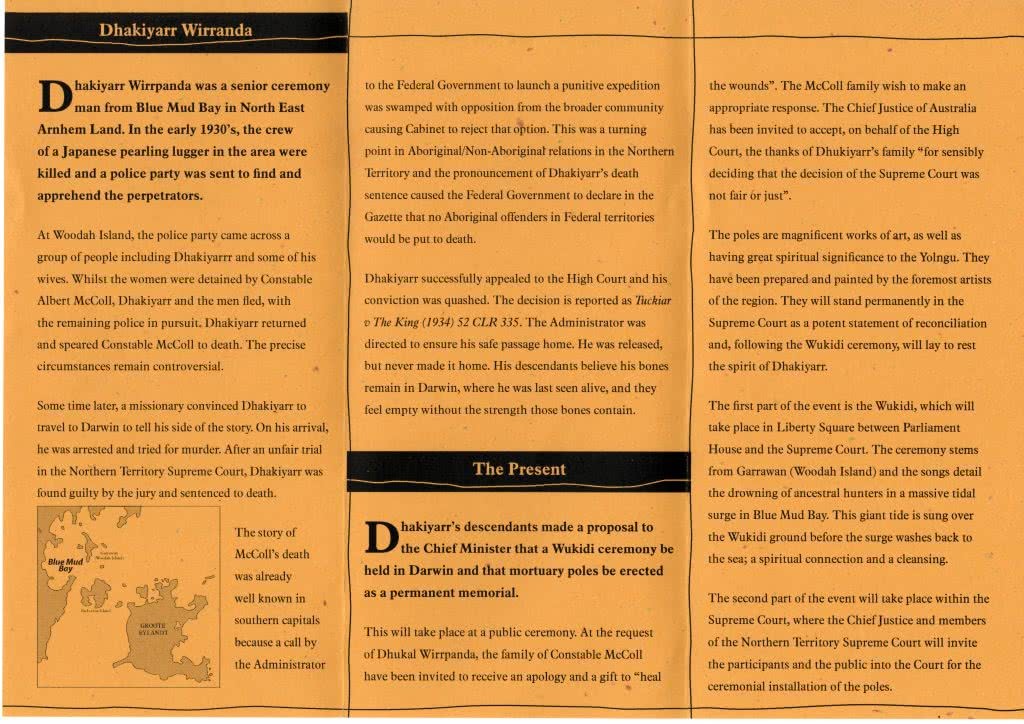

Just as white man’s law has never reached true closure, Makarrta has never been performed between the McColls and the Wirrapanda. On Saturday 28 June this year the McColl family was privileged to be part of a Wukidi ceremony of national significance in the white-Aboriginal relationship, and of major legal significance in Australian law.

The Wirrapanda people and other Yolngu tribes journeyed to Darwin to make peace with the McColl clan and apologise for past wrongdoings towards the family, to heal the wounds and to thank the High Court for sensibly deciding that the decision of the Supreme Court was not fair or just, thus averting a punitive expedition.

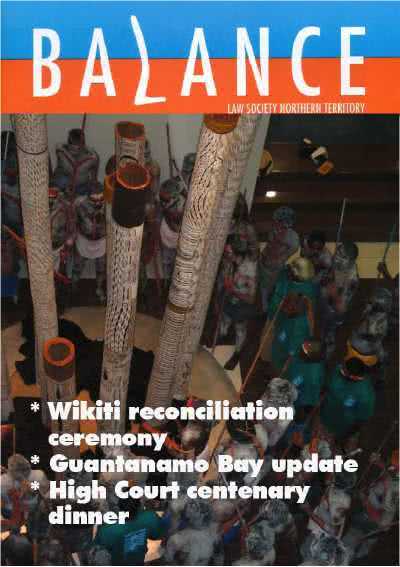

Around 20 descendants and relatives of Constable Albert McColl journeyed to Darwin to join the ceremony, which took place in the forecourt between Parliament House and the Supreme Court, where more than 100 tribal dancers—men and women with body paint and weapons—performed a cleansing of the grounds. The story was of a massive tidal surge that drowned ancestral hunters before washing back to the sea.

The women of the tribe surrounded the McColl family, protecting them as they were escorted into the Supreme Court.

Ahead the warriors and elders had entered to commence the ceremony of apologising and putting to rest the soul of Dh’a’kiyarr.

This included the ceremonial installation of nine mortuary poles or burial poles called Larrakitj. The ceremony was presided over by Justice Murray Gleeson, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, Justices of the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory and the Northern Territory Chief Minister, the Hon. Claire Martin, and her colleague, the Solicitor General, the Hon. Tom Pauling. The nine mortuary poles are exquisite artworks towering into the court foyer as a permanent tribute to reconciliation.

Through a series of dances and song the ceremony moved to a point where the armed tribal warriors directly confronted the descendants and representatives of the McColl clan before breaking a spear in front of them. At this point all hostilities between the tribe and the clan ceased.

What followed was an apology and exchanging of gifts between the Wirrapanda and the McColls. This is a historic event as it is the first time that such a Wukidi ceremony has been performed towards a non-Aboriginal family, culminating in reconciliation from Aboriginal to white.

The McColl murder has now effectively been settled out of court, using Aboriginal law, not white man’s law, whilst the most senior judiciary looked on. Through reconciliation and exchanging gifts both parties have settled the dispute and formed a mutual friendship.

The family of Dh’a’kiyarr presented gifts to the family of symbolism beyond our initial comprehension. A feather crown was presented by the sons of Dh’a’kiyarr. Such crowns are rarely worn and never gifted to white men. The crown conveyed the spirit of Dh’a’kiyarr. It is a sacred part of him. In gifting this crown the Wirrapanda gift the responsibility to all McColls to act as lawyers for the tribe representing the lessons learnt and the future dreams of the Wirrapanda people and the Aboriginal people in general. They understand that we can convey the message in ways beyond their capability.

The Wirrapanda people have extended their kinship to all the McColl families. In exchange the McColl families provided gifts, messages bound in traditional clan tartans, read poetry and extended messages of their goodwill. These messages conveyed their desire for peace and reconciliation.

On Sunday 29 June a small ceremony was held by the graveside of Albert by the family to unveil a small plaque from the family—finally, 70 years later. Some members of the Wirrapanda attended out of respect.

None of the family could have comprehended the significance of these days—in terms of its place in Australian legal history, the milestone in Aboriginal reconciliation or the deeply spiritual personal significance that such an apology could bring. The family had no influence over those events of 70 years ago. However, we all have the influence over events to come. We have all been moved and touched by the encounter, and we are all richer for it.