Background to an Epic

This story on the 1989 Westfield Run between Sydney and Melbourne is a record of an epic.

The author, Alf Field, is an avid runner himself and an enthusiastic member of the Sydney Striders Road Running Club – he was asked by fellow Sydney Strider and 1989 Westfield Run competitor, Graham Firkin, if he would manage his support team for the event.

His story tells of the planning, the preparation, the agony, and the ecstasy of this epic human endurance event.

It is essential reading for any runner contemplating such an event.

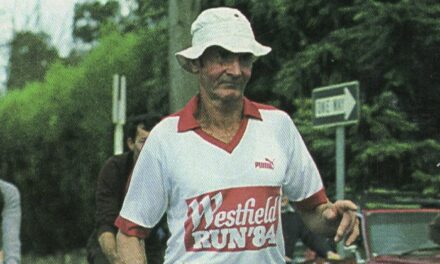

Graham ‘Firko’ Firkin is a dinkum battler. He is 51 years of age and has been a blacksmith for the past 36 years. In 1982 his health was a problem. He had high blood pressure, a high cholesterol reading, drank too much beer and smoked too many cigarettes.

The challenge of running in the 14-kilometer City to Surf motivated him to do something about his condition. When he started to train, he couldn’t run a single lap of a football field without taking a breather. But he persisted.

The City to Surf was conquered that year and, like thousands of other joggers, he sought greater challenges. The marathon, the ironman triathlon, and ultramarathons all became goals accomplished. In 1988 he decided he was ready for the ultimate challenge in human endurance, the 1,000 km Westfield Run between Sydney and Melbourne.

Cynics could say that Firko failed in his first attempt. He only reached Cooma, a distance of 292 km, before a leg injury forced him to withdraw. But when you consider that 292 kilometres equals almost 7 consecutive marathons then it is easier to appreciate the magnitude of his achievement. Indeed, it was a greater distance than Pheidippides ran in his legendary, run between Athens and Sparta in 490 B.C!

This story epitomizes the spirit of the Westfield Run which had emerged as the World’s toughest ultramarathon. By the time Firko approached Melbourne the lead runners had long since crossed the finish line and the crowds had gone. But this didn’t concern Firko because he was not in the event to win against the other competitors – he was simply out to win against himself.

Alf Field’s account of Firko’s epic is a tribute to the spirit of the man, his family, his friends, and his dedicated support crew.

Charlie Lynn

Race Director

Westfield Run ‘89

FIRKO’S RUN

Author: From the diary of Alf Field – Team Manager of Firko’s Support Crew

The Race: From Sydney to Melbourne commencing on Thursday, 18th May, 1989.

The Distance: 1,011 Kilometres.

The Runner: Graham Firkin, one of 35 starters

The Crew: Brian Colwell, Alf Field, Barbara Firkin, Toots Gray, Ken Gray, Barry Jones, Jack Nordish, Steve Nordish.

The Result: Completed the distance in 8 days, 16 hours and 25 minutes, finishing in 20th place. Fifteen competitors did not complete the course.

Condition of the Runner at the Finish:

Excellent. No blisters on his feet; no muscular or other injuries; sore legs; claimed to be “very tired” but partied on until sunrise on arrival in Melbourne.

Condition of the Crew at the Finish: Totally knackered!

“Give a big welcome to competitor number 8, Graham Firkin.” The announcer’s voice boomed around the Westfield Shopping Centre at Liverpool on Sydney’s south‑western outskirts, where the 1989 Sydney to Melbourne Ultra-marathon was due to start in 30 minutes.

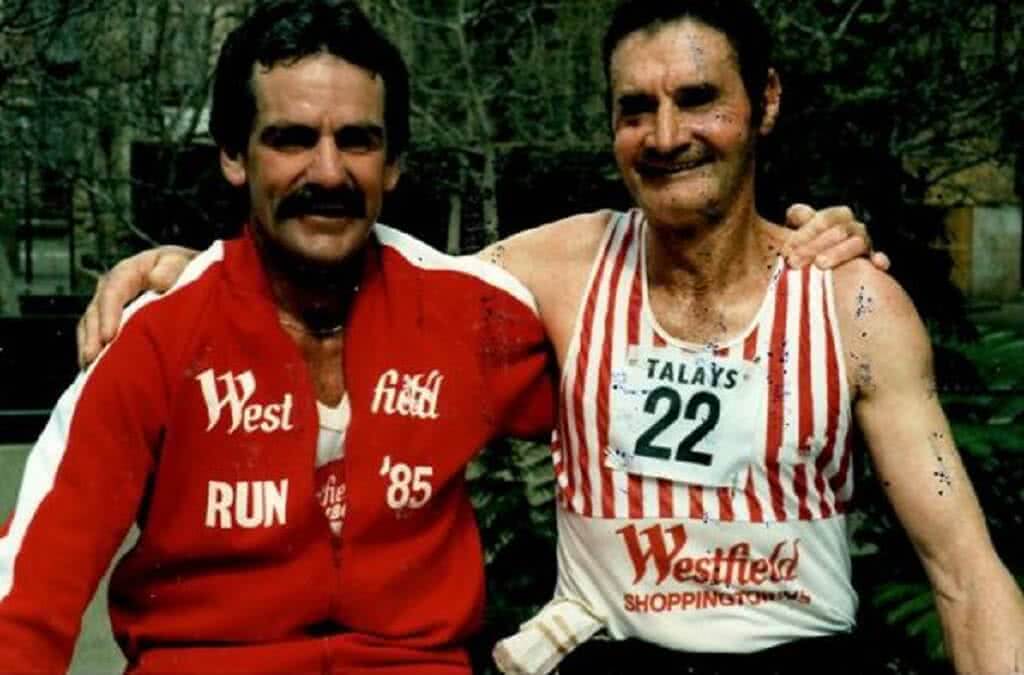

“Graham is aged 51, is a blacksmith and competed in the 1988 event, covering 292 kilometres before a leg injury forced him to withdraw,” the announcer continued. The polite clapping was drowned by raucous cheers from the group of Sydney Striders gathered to farewell Firko on his epic odyssey.

It suddenly struck me that we would soon be on our way, that the long year of planning and preparation was nearly over. Not that I had done anything much in the way of preparation. Barbara Firkin was the person who did the hard work. She was the one who wrote all the letters begging for sponsorship; she was the one who listed the multitude of items that would be needed and saw that they were purchased, planned the menus, bought the food, rented the vehicles, got the money in. It is certain that without her herculean efforts Graham would not have got to the start line.

It is also fair to say that without the financial and other help from all the sponsors, the project would not have got to first base. A big vote of thanks is owed to all sponsors.

I felt a bit of a heel. 1 had spent the past week trying to get my desk clear to enable me to get away for the trip. 1 hadn’t been able to help the rest of the crew with the myriad of final preparations and packing of the vans. 1 need not have worried. Firko had a little surprise in store for me.

We hadn’t really discussed what my particular function was to be on the team. As far as 1 was concerned 1 was going to help in whatever capacity 1 could. An hour before the start Firko sprung his little surprise: “Alf, 1 want you to take charge. You do all the calculations, make the decisions and get us to Melbourne. What you say the crew and 1 will do.”

Firko had obviously noticed on the trip last year that 1 like to throw my weight around and so 1 became saddled with this awesome responsibility. It was, however, typical of Firko’s own planning for the trip. This time it was totally professional, a complete contrast to last year. He had thought about every last detail and planned with great care. He had realised that it was important to have one person with absolute authority to make the tough and difficult decisions which abound on such a trip and which often need to be made in a hurry. He had decided that I was to be that person.Thanks Firko!

His crew selection had likewise been mulled over. His final selection worked brilliantly well in the long, tiring and testing hours on the road. The crew was always a most harmonious bunch united in their desire to see Firko safely into Melbourne.

The professionalism extended right down to his shoe selection. He had bought the top of the range, Nike Stab‑airs, and eventually wore only one pair all the way to Melbourne, arriving there without a single blister. Quite incredible. When 1 think of how often he changed shoes last year to no avail…

The gunshot reverberated around the enclosed shopping centre and the red and white garbed runners burst forward like a tidal wave, smiling and waving to friends, oblivious to the trials, tribulations and pain which lay in store for them over the next week.

For a few minutes it was bedlam. Husbands saying farewell to their wives, Crew members dashing to their vehicles and onlookers cheering the intrepid runners.

We were on our way and 1 think that each of us was wondering what dramas the next week had in store for us. Was Firko really capable of getting all the way to Melbourne? Did 1 have the knowledge and ability to keep him together both physically and mentally for such a long time? All the problems we experienced last year were suddenly very fresh in my mind.

The first day was used to establish the routines which were to become ingrained over the next week. Firko was to eat regularly in small quantities, about every hour. His diet consisted of mashed vegetables for his main course and canned fruit in Jelly for dessert.

We had discovered last year that Firko was able to absorb mashed vegetables without any ill eff ect and they provided quick energy as well as all the minerals and trace elements that his body required. The only problem was the monotony of the diet, which 1 tried to counter by allowing him to choose whatever he wanted to eat at his major rest stops. This gave him something to look forward to every 12 or 14 hours. 1 also allowed him a low alcohol beer on these occasions.

Initially Firko was quite rebellious about continually eating vegetables and on one occasion grabbed an Esky belonging to some roadside workers as he ran past. He was heard to mutter something about their lunch being better than the crap Alf was feeding him as he was forcibly dispossessed of the Esky!

Later in the race, after he had lost weight and was running on negligible reserves, he began to actually ask for his vegies as he was then better able to appreciate the benefits that flowed from them.

The other vital part of his diet was his drinks, which were needed to maintain both his fluid and blood sucrose levels. I had spent the best part of the past year accumulating supplies of a carbohydrate polymer powder called Endurolode. It is a South African product which for political reasons is not available in Australia. Every time 1 heard of someone going to South Africa or had visitors from that part of the world, they were instructed to bring me a few cannisters of the vital powder.

When mixed with water, Endurolode is a drink which provides the body with a quick glycogen boost, which is used first by the body, thus allowing the body’s natural reserves of glycogen to remain intact. This drink played a big part in keeping Firko going and prevented him from suffering many of the nasties which afflicted other runners.

Another product which 1 obtained from South Africa in limited quantities was something called a “Squeezy”, which was simply EnduroIode in a viscous liquid form, rather like condensed milk, and packed in plastic sachets. It provides an even quicker burst of energy and 1 felt they would be useful during the nights when Firko would not require quite so much liquid.

The race consists of a number of segments which must be completed within a stipulated time or the runner is disqualified. The first such cut-off point was in Goulburn, 164 kms from Sydney and the time allowed was 25 hours. As Firko had covered more than 200 kms in a 24 hour race, it was considered that he should cover 164 kms in 25 hours without any difficulty. Consequently it was decided to give him a couple of hours rest at Mittagong, some 77 kms from Sydney.

He was following a sequence of 10 minutes running, 5 minutes walking, with stops about every hour for a stretch. The latter was something which he had not done last year and which 1 had felt had been detrimental to his performance then. This routine plus the correct food and drink seemed to be working well and Mittagong was reached without major difficulty at about 8.40 pm.

1 had allowed for a 2 hour stop in Mittagong but it was nearly two and a half hours before we were on the road again. 1 was not particularly worried as we had plenty of time in hand to make Goulburn.

The only incident of note that night took place at a point which Firko subsequently named Shit Hill. Included in the equipment on this trip was a toilet scat mounted on foldup legs, the idea being that if Firko needed to go while we were out in the sticks he could take his seat out behind the nearest bush and do his business.

It was at Shit Hill that Firko received his first urge to use his foldup toilet seat. The seat was duly set up a discreet distance from the road and Firko went about his business. He was just about finished when he felt a little uncomfortable and tried to adjust the seat which promptly collapsed, depositing Firko in his recent deposit.

The language was something to behold. Even the cows in the nearby field hurriedly moved away and Barbara was muttering that she had thought she had finished with cleaning babies’ dirty bottoms.

Our first dawn found us less than 30 kms from Goulburn and we were all in good spirits because Firko was going so well. A few hours later we crested the hill about Goulburn, and soon passed the cut-off point with almost 2 hours to spare. 164 kms covered in a little over 23 hours. Not bad at all.

1 ruled a two hour rest period and at exactly 1.00 pm we were on the road again. The next cut-off point was 92 kms away in Canberra at 4.00 am next morning. This gave us 15 hours to cover the distance and 1 calculated that we would make it with 2 hours to spare.

I felt that the leg from Goulburn to Canberra was going to be crucial in assessing Firko’s chances of getting to Melbourne. It was midway through this section last year that he collapsed, totally exhausted. Also by the time we reached Canberra he would have been on the road for around 39 hours with only 4 hours rest. He had to cover this leg in some style if he was going to have any chance of getting to Melbourne.

1 needn’t have worried. He wasn’t even aware of passing the point of last year’s trauma, but 1 must confess to a sigh of relief once we were past it.

Barbara had told me that Firko only wanted Barbara, Steve Nordish and myself to join him out on the road. This meant that the three of us had to share the duties of shuttling his food and drinks out to him while Steve and I had to do most of the motivating, cajoling and assisting through the inevitable low spots. This was not a reflection on the rest of the crew, but merely Firko’s view that the 3 of us understood him best.

The result was that Steve and I spent long periods out on the road with Firko, especially in the hours after midnight and during the latter stages of a leg as we were approaching a cutoff point.

Thus it was that both Steve and 1 were out on the road with him as we made our way down the mist shrouded Northbourne Avenue towards the cutoff point ill central Canberra. Firko was a model patient, following every instruction 1 gave him to tile letter and never failing to respond when 1 asked for an effort. So much so that we arrived at the Canberra cut-off at 2.00 am exactly, precisely to the minute 2 hours ahead of the cut-off, as 1 had calculated 13 hours earlier in Goulburn.

At the motel, where 1 calculated we could afford a 3 hour rest, we examined Firko’s feet. I was amazed because they looked as if he had hardly walked around the block let alone run 255 kms. There were no blisters, no weals, no red blotches or bruises, just his normal clear white flesh. It was the first time on the trip that 1 had the feeling that God must be with this man.

Disaster very nearly struck us in Canberra, and from a most unexpected source. 1 set my alarm for 5.00 am and went to sleep instantly and deeply as I had had about the same amount of rest as Firko had had. I became conscious of someone beating a drum next to my bed. “Go away” 1 mumbled and rolled over. The noise from the drum wouldn’t go away. Annoyed 1 sat up in bed. Someone was knocking on the door.

1 staggered around in the darkness trying to find the door in the unfamiliar dark room. It was Barbara. “Wazzamatter” I muttered, cross that she had disturbed my sleep.

“It’s quarter to six. Firko is ready to go and is shouting for his crew” she replied. That woke me up with a jolt. Incredibly 1 had slept right through the alarm, as had the other four crew members sleeping in the same room.

Although everyone was galvanised into action, it was 6.20 am before we got back on the road, nearly an hour later than 1 had planned. 1 felt sick because 1 knew that the next leg to Cooma was going to be a tough one with lots of severe climbs, particularly during the latter stages as we passed through the foothills of the Snowy Mountains.

The distance to Cooma is 115 kms from Canberra and we needed to get there by 1.00 am next morning, only a bit more than 18 hours away. It was going to be tight, but 1 kept my concerns to myself. Stick to the routine and see how we go.

Around 9.00 am we had cause for a small celebration as we passed the spot where Firko was forced to withdraw in agony last year. This year a quick photograph and a celebratory beer. What a contrast!

Our delayed start from Canberra had left us last in the field, at least of those who were still in the run. Firko was progressing so well that we soon began to see the flashing amber lights atop other competitors vehicles. Gradually we pulled up to them. First we passed the irrepressible Cliff Young. Later in the afternoon Firko sailed past the Japanese competitor, Norio Wada.

Dusk was beginning to settle and 1 sent the second van into Cooma to arrange some accommodation for us. This was something we seemed to be doing at each stop as we invariably arrived in the wee hours. When they returned tile first van went for a run to charge its batteries, a daily necessity caused by the long hours of ultra‑slow travel.

Cooma was still 45 kmsaway and 7 hours to the cut-off. 1 calculated that we had half an hour to spare if Firko kept going without any breaks. This was a pretty tough assignment as he had already been on the road for nearly 12 hours since Canberra without any rests other than his brief stretching breaks. And 1 knew that about 75% of the remaining 45 kms were going to be pretty severe uphill climbs.

It was going to be dreadfully close and 1 rued the hour we lost in Canberra due to my sleeping through thealarm. 1 wondered if 1 would ever be able to forgive myself if Firko got eliminated for not making the Cooma cut-off. We just had to get there.

At his next stretching break we had a gentle chat. “Are we going to make it?” Firko asked. “Sure” I said, “provided you have no rests and reduce your stretches to every two hours.”

“How much will we make it by?”

“By five minutes” 1 lied.

He responded as 1 knew he would: “Shit, we had better get moving then,” and he immediately turned and started running.

1 had brought enough Squeezies to be able to give Firko about 5 per night, but this was an emergency. There was no point in missing the cutoff and having squeezies in stock. 1 resolved to cut into our stock to whatever extent was necessary to get to Cooma on time. 1 warned Steve that we were both going to need to be out on the road for the next 6 hours.

Firko responded splendidly both to the Squeezies and to the demands of the occasion. Steve and I set him a tough pace and he never wavered. Naturally he complained about some of the hills, but then so did 1, and I hadn’t covered 340 kms as he had.

We continued to pass other runners and 1 pitied them for 1 knew that if we were barely going to make the cut-off, then they could have no chance of doing so. Their race was over.

I will never forget the last 20 kms into Cooma. It was a bitterly cold, crystal clear night and we were all wearing our warm gear, including gloves and beanies. Every 5 kms 1 recalculated our position relative to the cut-off and found that we still had a steady 30 minutes in hand for emergencies.

Firko had been on the road 16 hours since Canberra without a break and 1 monitored his condition continuously. A couple of serious cramps could easily cost us our precious 30 minute buffer, but 1 was more concerned about Firko reaching a state of total exhaustion. Every time 1 perceived him to be flagging and not maintaining the correct pace, 1 ordered another Squeezy for him.

The last 10 kms were covered on grit, determination and Squeezies every half an hour. It was amazing how he responded to the Squeezies. They were a real find.

Another thing which helped considerably was the speaker mounted on the front of the first van through which tapes could be played. It was on this section that 1 first became aware of the lift that Firko got from listening to a tape of hymns and spiritual songs by Burl Ives. This was the second time on the trip that 1 felt that God was looking after Firko.

At 1.00pm I sent the second van ahead to allow at least some crew members to have a shower and clean up before we arrived. I told them that 1 anticipated being at the cutoff point, which was on the outskirts of Cooma, at 12.30 and that we would get to the motel in the centre of Cooma at 1.00 am.

Our log book shows that we passed the cutoff point with 29 minutes to spare. 1 must confess to a bit of deception. I did not tell Firko the good news as 1 wanted him to make his way to the motel and not have to backtrack when we restarted. We kept looking for a non‑existent ‘Welcome to Cooma” sign which 1 told him was the cut-off. Just before 1.00 am we reached the motel and gratefullygot into bed. 1 only removed my shoes before diving between the sheets.

The next leg to Bombala is about 90 kms and we were allowed 22 hours to get there. This seemed fairly comfortable seeing Firko had just completed 115 kms in 18 hours, so 1 felt justified in allowing hima slightly longer rest ‑ 4 hours. That would leave 18 hours to cover 90 kms, or 5 kms per hour, virtually walking pace. Should be a doddle 1 thought as I wafted into dreamland.

It was tough getting going again just after 5.00 am. It was still bitterly cold and fog had settled down to ground level. Visibility was reduced to about 50 metres. Firko was wearing his black balaclava and looked for all the world like Ned Kelly reincarnated.

Suddenly we picked up conversations on the CB radio. It was Terry Cox’s crew. From what they were saying it was quite clear that Terry was very much in the race. Yet he was one of the seven runners behind us going into Cooma. We knew that he could not possibly have made the cut-off in time. He had been running with his son, Terry Cox Junior, and the youngster had been in a lot of trouble when he passed them.

We called them up on the CB to ask what had happened. It transpired that the Race Director had belatedly changed the cutoff time by an hour which enabled the laggards to get into Cooma without disqualification. The Race Director had stated that he had set far too tough a cut-off time for Cooma.

1 was stunned. We had needlessly put Firko through the wringer to get him to Cooma in time and, almost as bad, we had needlessly used up half our meagre stock of Squeezies. 1 knew that Firko would take the news badly and yet 1 had to tell him.

We discussed the issue for some time. We were naturally pleased for the other runners that they could continue. They had all spent many thousands of dollars renting their vans and equipment. Their crews had all taken leave and volunteered their services. It would have been a great shame if they had been eliminated.

It was simply bad luck for us that the cut-off time had been changed after we got to Cooma. It would have been a major bonus if we had known about it 10 or15 kms out. 1 put it to Firko that the race organisers now owed us a favour and that we might just need a favour before we got to Melbourne. This seemed to calm him down and, indeed, was to prove prophetic.

That day on the road to Bombala turned out to be anything but the doddle 1 had anticipated. Firko was visibly dragging his heels. The effort to get to Cooma had taken a great deal out of him while the change in the cut-off time was bad psychologically.

It became a long hard slog over extremely undulating terrain. We were still traversing the fringe of the Snowy Mountains. Steve and 1 were destined to spend long periods out on the road trying to motivate Firko and keep his mind on the job. We had to resort to periodic 15 minute rests with occasional 30 minute breaks.

Fortunately, after nightfall Firko picked up noticeably and we reached Bombala around 9.30pm, about an hour and a half before the cut-of f time. All the cut-off times had in fact been extended by an hour following the change to the Cooma cut-off time but Firko, in a fit of pique, said that he wanted to stick to the old cut-off times.

Firko and the crew were in desperate need of rest so 1 decided on a gamble. If I gave him a long rest he might recover his energy levels much better than from a short break and be able to make up the ground by moving faster the next day. I rostered 6 hours sleep for everyone, which meant that the full break was about 7 hours. It was blissful and did the trick.

The next day, Monday, was by far the easiest and nicest day we experienced. The dawn was perhaps the most magnificent 1 have ever seen. The colours and cloud formations were stunning and seemed to cover the entire firmament. It set the tone for the day.

After a couple of hours we moved off the edge of the escarpment and started down the scenic Cann River valley, through dense forests and occasionally along the banks of the Cann River itself.

Firko was happy and running comfortably. The crew were relaxed and Brian and Jack took the opportunity to go for runs up ahead through the forest. Even a brief rain shower could not dampen our spirits.

Several notable events occurred on this section. In quick order we passed the 500 km mark, the halfway mark and the Victorian State border. The latter seemed to give Firko a special lift.

We also received the first of the newsletters which contained many messages of encouragement for Firko, all of which were greatly appreciated.

The only sour note during the day was when Jack Nordish took over the driving of the lead vehicle. He sniffed the air and asked Barbara whether she was cooking fish only to be told that it was my running shoes that he was smelling.

At about 7.00 pm we pulled into a motel in Cann River, having covered 90 kms during the day. The next cutoff point was still some 77 kms away at a town called Orbost. Firko’s strong performance during the day enabled me to allow him a 3 hour sleep in Cann River.

When we got underway again, it was back to the serious business. For starters, there is a long 40 km climb out of Cann River. It seemed to take forever. The wind was howling but unfortunately we were sheltered by the dense forests that we were travelling through.

I insisted that Firko walk up all the hills to conserve his energy, which meant long periods of walking when Steve and 1 took turns at keeping him company. Burl Ives and Rocky were the main musical fare. Steve said that he counted 25 separate renditions of the Burl Ives tape on that leg! While he came to detest this tape, it actually grew on me. 1 am listening to it as 1 type this and it is astonishing how vividly it brings back the memories.

The trip into Orbost was relatively uneventful. Once we cleared the mountains Firko got back into his easy rhythm, alternating 5 minutes running with 5 minutes walking. He was running comfortably and showing no signs of stiffness or pain anywhere.

One incident about 10 kms outside of Orbost is worth recording. We had gradually caught up with Terry Cox. From the slow pace at which he was travelling we deduced that he must be in some sort of trouble.

I was out on the road with Firko at the time and as we started to get close to Terry, he fell forward flat on his face and didn’t move. His crew rushed to his assistance and by the time we drew level with him they had him on his feet on the side of the road. He was bent over retching and looked all in.

1 turned to Firko and told him that no matter how badly he wanted to get to Melbourne, 1 was not going to let him do it if it was necessary to drive him to the same condition that Terry was in at that moment. Firko had clearly been shocked at Terry’s condition and he agreed with me.

“I don’t want my wife, kids or family to ever see me in that condition” he said quietly. Fortunately we understood each other.

I thought that Terry Cox would have to pull out of the race, but ultra‑marathoners have their own form of insanity. Terry got going again, didn’t stop for a rest as we did in Orbost, and he remained ahead of us all the way to Melbourne!

When we got to Orbost, Firko had been on the road for exactly 5 days and had covered 629 kms, an average of nearly 126 kms per day. It was hard to believe that the leaders were some 350 kms ahead of us and were approaching the finish at that time. One certainly gets a greater respect for the enormity of these performances when one is out there day after day, living the whole experience and maybe covering 50 or more kilometres per day oneself.

From Orbost the course loops down to the coast at Lakes Entrance and then curves back inland to Bairnsdale, which was the next cut-off point. It is about 60 kms to Lakes Entrance and a further 37 kms from there to Bairnsdale. After allowing Firko 4 hours sleep we were left with 19 hours to cover the 97 kms to the Bairnsdale cut-off. It should be a doddle, 1 thought, but once again events were going to prove me wrong.

Up to Orbost 1 had controlled everything that Firko did. I told him when to run, when to walk, when to eat, when to sleep, what to eat, what to drink. About the only thing 1 did not control were his bodily functions and, believe me, he functioned often. If anybody is looking for a donor with a good quality kidney I can recommend Firko’s. They are in perfect condition! 1 can vouch for it as 1 carefully observed more than 50% of his piddles to check the colour of the urine and to be sure that it contained no blood. If Firko could have found a sponsor who would donate 50 cents for each of his piddles on the road to Melbourne, there would have been no need for any other sponsors!

Thus, it was at Orbost that Firko rebelled. In the nicest way, of course.

“Alf, do you mind if 1 walk and run as I feel up to it?” he asked plaintively.

After 630 kms 1 figured that he was probably getting the hang of it, so 1 agreed. In any event 1 was feeling pretty bushed and a few extra hours shuteye was very appealing. Once 1 was sure that everything was going well I climbed into the bunk above the driver’s cab in the second vehicle and slept for nearly 4 hours.

1 was awakened by this terrible earthquake, Indeed it was several earthquakes. 1 was in a very tall building and when it eventually collapsed I woke up to find that it was the shuddering of the van as it started and stopped that was causing the earthquakes.

Firko was still going well and had covered more than 1 had expected him to while 1 was asleep. We were about 3 hours out of Lakes Entrance and, as had become customary, 1 joined him for the last pull into town.

1 had promised Firko half an hour’s break in Lakes Entrance where he could have a change of clothes, let Steve massage his feet and have a proper meal. Firko had asked for steak and kidney pie and to my amazement, that is exactly what Barbara produced for him.

Firko still had 8 and half hours left to cover the 37 kms to Bairnsdale, working on the old cut-off time and an extra hour if we used the revised cut-off time. It looked pretty comfortable and my idea was to get to Bairnsdale with two or more hours in hand so that Firko could have a good rest there.

There is a long climb out of Lakes Entrance. Not nearly as bad as the climb out of Cann River, but still quite a tough slog. We took it fairly slowly, taking nearly an hour and a quarter to complete the 6 km hill.

Once on the level Firko started his walk‑run‑walk routine. He had been doing this for about 15 minutes when suddenly he veered across the road, staggering into me. I could see that something was seriously wrong and sat him down on his haunches.

“What’s the matter, mate?”

“Dizzy. Just dizzy” he mumbled, “Can’t stand”.

“Right, you are going straight to bed,” 1 ordered. He just nodded his assent.

He had clearly been overcome by exhaustion. What concerned me was that 1 was right next to him and 1 had not been able to pick up any signs of imminent collapse.

There was a dark, deserted filling station 50 metres up the road. We pulled the vans in there and laid Firko out on the bunk. He was snoring before we had removed his shoes and covered him up.

Some of the crew stretched out for a sleep, others mulled around outside. 1 sat in the cab to do a bit of figuring and thinking. It was exactly the situation 1 had dreaded. I kept thinking of the column in the daily newsletter which gave the reasons for those runners who had withdrawn. Half of them had simply withdrawn from “exhaustion.”

We still had 29 kms to go to Bairnsdale. If 1 let Firko sleep for an hour, we would have either 6 or 7 hours to get him to the cut-off, depending on which cut-off time was used. It was going to be a resurrection job, similar to that which we had to do on him last year on the road to Canberra. Lots and lots of vegies, no running, slow walking and a few Squeezies. Maximum speed would be 5 kms per hour, so a full 6 hours would be needed. An hour’s sleep was all we could afford, but we would still be left with the hour from the revised cut-off as an emergency buffer.

I went to look for Barbara to tell her the news. 1 found her on her own, down a side road quietly sobbing.

“It means so much to him,” she said, wiping the tears away. “He is desperate to make it to Melbourne.”

“1f there is any way of getting him there without half killing him, we’11 find it,” 1 promised her.

What had looked like a doddle had become a desperate race to make the cut-off. 1 blamed myself for allowing him to do his own thing. He had obviously overdone the running. 1 blamed myself for having a 4 hour sleep. If 1 had been awake 1 would have seen the huge effort he put in to make Lakes Entrance so quickly.

Nothing for it now but to institute Operation Resurrection. Lots of vegies and lots of slow walking. And once again it worked. After some two hours Firko was looking as bright and chipper as he had been at any stage in the run. Better still, he had suffered no further bouts of dizziness.

In fact, he was looking so good that when we came to a gradual decline, 1 suggested that we trot down the easy half kilometre or so. When we got to the bottom of the hill 1 was shocked at the change in his condition. He had lost all his chirpiness, his face was drawn and grey and he looked as if he was going to be ill.

Running was immediately banned and within 30 minutes he had recovered to the point where he was smiling and cracking jokes again. After another 30 minutes 1 decided to try another trot down a gentle decline, but the result was identical to what had happened an hour earlier. The smile faded to be replaced by the drawn, grey look.

My heart sank as I diagnosed what was happening was that when he started running, the pain was causing his body to go into shock. We were going to have to walk all the way into Bairnsdale. Worse still, we were probably going to have to walk the remaining 300 kms to Melbourne.

1 tried to explain to Firko what was happening to him but I’m not sure that he understood fully. “Walk to Bairnsdale and we’ll worry about it from there,” 1 said.

Firko looked dejected. “I’m sorry to be holding you up,” he mumbled.

I put an arm around his shoulder. “Mate, if there is anything which is going to make me very cross, it is you apologising and feeling sorry for yourself.”

Some weeks after the event, Firko confided that what 1 had said had been like a slap across the face, that it felt as if he was back at school. He didn’t apologise again on the trip. Nor did 1 ever have the impression that he was feeling sorry for himself.

The long walk into Bairnsdale was highlighted by the arrival of Firko’s son Shane, who was stationed at the Air Force Base at Sale. It was a welcome moment for Firko and helped to break the monotony.

When it became apparent that Firko was going to be able to walk to Bairnsdale and arrive within the original cut-off time, 1 allowed myself to think about the next leg, which was 120 kms to Traralgon. From cut-off time in Bairnsdale to cut-off time in Traralgon was 24 hours, with an extra hour if we used the revised time.

The problem was that 1 had a runner who couldn’t run and was walking at about 5.5km per hour. He was going to need 22 hours to cover the distance at that rate, but he also needed a rest. 1 decided that we had no alternative but to start using the extra hour available from the revised cut-off times. If he walked 40 kms, slept for an hour, walked another 40 kms, slept another hour and then hightailed it to Traralgon, it would take exactly 24 hours.

If we followed this schedule, then 1 could only give Firko a 90 minute break in Bairnsdale. As I could see no other alternative in the circumstances, that is what we did. There was barely time for Firko to shower, to have his feet massaged by Steve and get an hour’s sleep before we were on the road.

1 walked with Firko for the first 3 Hours out of Bairnsdale in order to try to get him up to 6 kms per hour pace, thereby building up a small buffer for emergencies. We did cover 18 kms during those 3 hours, but it was quite a humiliating experience for me. At the end of the 3 hours my feet were sore, 1 had a couple of blisters and 1 was exhausted. My respect for Firko’s stamina and guts went up another notch as he continued to stride out towards the setting sun.

It took 7 hours for Firko to walk those first 40 kms, an average of 5.7 km per hour. This was slightly better than the 5.5 km per hour that 1 had budgeted on, so we had a small buffer. After an hour’s sleep, a change of clothes and another foot massage, Firko was walking again. We were into our seventh night on the road.

Firko had lost a considerable amount of weight and his buttocks had almost disappeared. His face was haggard and drawn, and his pace was gradually slowing. As midnight approached, I started to get alarmed. We had only covered about 16 of the next 40 kms that I had scheduled before his next hour’s rest. At the pace he was going at, we were not going to make the Traralgon cutoff. Firko was approaching total exhaustion and there was nothing I could do about it.

Three kilometres further on, while he was having a stretch, he asked: “How much further is it to my next rest?”

“About 12 kms,” I replied. His shoulders sagged.

“Alf, do you think 1 could have half an hour now and reduce the next rest by half an hour?”

My heart went out to him. It was the first time since we had left Sydney that he had actually asked for a rest. 1 knew how much it had cost him just to ask. 1 also knew that he was finished, both physically and as far as the race was concerned. He had to have a decent rest and after that there was no way that he could make the cutoff in time. It was crunch time.

“No mate, you can’t have half an hour. You are going to have a full hour, maybe more.”

We were still 35 kms from Warragul when he asked for another 5 minute rest. What he needed was about 12 hours sleep. 1 called a halt and put him to bed. Even if we kept going, we were not going to make the cut-off. In fact, 1 was doubtful that he would even get to Warragul if we kept going without giving him a rest.

It was time to call in the debt that 1 believed the Race Organisers owed us for the cockup at Cooma, which now seemed years ago. The official dealing with our section of the field was Firko’s friend “Mountain Man’. 1 knew that he would be along shortly as he always arrived at dinner time.

Sure enough, ten minutes later Mountain Man pitched up. 1 explained the situation to him and asked if 1 could use the car telephone to talk to Charlic Lynn, the Race Director and the man with the final authority.

1 explained to Charlle how we had been prejudiced by the events at Cooma and why 1 felt that the Race Organisation owed Firko a favour. 1 told him of Firko’s condition and said that 1 was not prepared to drive him into ground in order to make the cut-off point at Warragul. 1 asked for official permission for a late arrival at the cut-off point for Firko.

Fortunately Charlie was very friendly and accepted what 1 said about Cooma. He agreed to allow Firko to reach Warragul after the official cut-off time and to continue on to Melbourne as an official runner. He said that he would issue instructions accordingly.

Later 1 checked with Mountain Man and also with the driver of the night safety van which followed the last runner in the field after sunset and found that Charlie was as good as his word. He had told them that we were to continue to Melbourne even if Firko missed the Warragul cut-off time.

After an hour 1 got Firko up again and we set out for Warragul. It was tough going as Firko still did not seem to have anything in reserve and the Endurolode was not perking him up. The Race Doctor had given us a can of “Maximum” to try. This is an Australian made product similar to Endurolode, but 1 had refrained from using it because 1 didn’t want to change a winning formula. 1 decided that it was time to give Maximum a go and it produced an immediate positive effect. Perhaps Firko was saturated with Endurolode.

‘Were you there when they crucified my Lord,” “Sometimes it causes me to tremble, trrreemminbbbllleee.”

The gravelly tones of Burl Ives’ voice filled the night sky for the umpteenth time. 1 was out on the road again with Firko, but this time there was no respite. 1 had discovered that Steve Nordish had a serious ankle injury which he had successfully concealed from me for two days until he could no longer walk. He was now resigned to a driving and foot massaging role for the remainder of the journey.

“He walks with me and He talks with me, and tells me 1 am his own.” More Burl Ives. Seemed appropriate.

Ever so slowly the hours and the kilometres ticked by as Firko and 1 strode up the long, straight, dark road. 1 was too concerned about his weakened state to leave his side.

Midnight came and went. Finally at 2 am, the cut-off time at Warragul, we were still some 7 km from the town. 1 felt exceedingly grateful that we had a debt to call up and that it had been honoured.

“Come home, come home, Ye who are weary come home,” “Earnestly, tenderly, Jesus is calling.”

Burl Ives droned on in the background. Eventually the lights of Warragul appeared ahead of us.

It was 3 am and 1 was exhausted. Heaven knows how Firko was feeling. To me it seemed like a miracle that he was still on his feet. Another 2 kilometres into Warragul and then bed.

I noticed an official Westfield Run car pull up and the Race Marshall got out. He trotted up, smiling and waving to the bleary‑eyed crew. 1 thought that it was jolly nice of him to come out at 3 am in the morning to give Firko a helping hand into Warragul.

Firko was walking at the time. I was on his right hand side carrying the drinks bottle. The Race Marshall joined us on Firko’s left hand side.

“Graham, this is something which is very hard for me to do,” said the Race Marshall, “but rules are rules and the Warragul cut-off time has already passed.”

1 suddenly realised that he was not there to help Firko and that he was on the verge of withdrawing him from the race. I am a very easy‑going person and used to be able to count the number of times that 1 have blown my cool on the fingers of one hand. 1 was about to start on my other hand.

1 simply exploded, fumes were literally coming out of my ears. No doubt the lack of sleep, the physical exhaustion and the emotional pressure of keeping Firko on the road all took their toll.

Suddenly 1 was poking my forefinger in the Race Marshall’s face and yelling at him.

“Who the effing hell do you think you are coming here to withdraw this man?” 1 think that the words were probably somewhat stronger. “You better get on your effing phone and check your effing facts with your effing Race Director before you do anything that you might regret. We have official permission to be late at this cutoff.”

“When did you speak to Charlie,” the Race Marshall wanted to know, quite taken aback by my outburst. 1 told him and he scurried off with his tail between his legs to check what 1 had said. A few minutes later he returned to say that everything was as 1 had said and that we were to continue. He left muttering under his breath about not having been informed and that Charlie should not shoot from the hip like that.

It gave us something to talk about over the last little hike into Warragul.

Firko still had 103 kms to cover to the finish line in Melbourne. To get there at some sort of respectable time, we had to be on the road again at 6.00 am. That gave us about two hours for a much needed sleep.

“Wake up, Alf, 1 heard your alarm go off.” It was Toots shaking my shoulder. Once again 1 had slept right through the alarm.

Steve Nordish was propped up on one arm on the adjacent bed. “Last day,” he said cheerfully.

“What do you think the odds are of making it?” 1 asked him.

“1 never had any doubts that he would make it,” he said. “The only time 1 was concerned was before Traralgon. He’ll make it now.” 1 wasn’t so sure. I knew how close Firko had been to collapse the previous day. It was a question of crossing fingers and keeping going. I was determined that we would get him there, even if we had to carry him the last 50 kms.

We had been ordered to have someone on Firko’s right all the way from Warragul to Melbourne, in case he lurched to the right into the traffic, which was expected to become increasingly heavy. This was the opportunity to give the rest of the crew a chance to be out on the road with Firko and Ibelieve that it was also the time that he was ready for a change of company. A roster was prepared so that everyone could have a turn out on the road. I decided that I wouldsave myself for the last 30 kms when 1 might be most needed.

1 had phoned my wife, Rosanne, when 1 began to get confident that Firko was going to make it to Melbourne. 1 suggested that she might like to fly down on the Friday morning and be with us on the final day. It would also enable her to bring us a packet of Squeezies which 1 felt would be sorely needed before we got to the finish line.

From about 10.00 am 1 was scanning the oncoming traffic, looking for Rosanne. Eventually there was a toot as she flashed past on the other side of the double highway. Thell she was parking up ahead of us and running towards us with a broad grin on her face.

“I’ve never seen Rosanne without a smile on her face,” remarked Firko as she rushed up and gave him a peck on the cheek.

As we walked back towards the van to greet the crew, Rosanne said: “1 hear that Firko has been withdrawn from the race. What has happened?”

1 stopped in midstride. “What are you talking about?”

“1 was listening to the news on the car radio and heard that Firko has been withdrawn from the race but is being allowed to complete the course as an unofficial runner.”

Once again 1 was flabbergasted. This was completely contrary to my arrangements with Charlie Lynn, the Race Director. 1 suddenly realised that we had not seen a race official all morning. Was Firko really out of the race? Did this mean that he was not going to be recognised as a finisher? After the incredibly courageous effort that he had made, was he going to be denied a Finisher’s Medal and recognition in the Race Records as a finisher?

We discussed the situation with the rest of the crew and decided that we would not mention anything to Firko until we had further information from a race official. The hours ticked by, but no race official appeared.

Eventually Firko had covered 25 kms. 1 had decided to break the journey into 4 sections of about 25 krns each, allowing Firko an hour of sleep at the end of each section.

About halfway through the second 25 km leg I noticed a television crew up ahead. 1 knew instinctively that they were going to question Firko about the circumstances of his withdrawal, something which he still knew nothing about. 1 dashed forward in the hope that 1 could fend them off.

Sure enough, the interviewer immediately launched into questioning Firko about why he was continuing after he had been officially withdrawn. 1 countered by asking from where they had got their information that Firko had been withdrawn. The interviewer replied that it came from an AAP‑Reuters wire report. My heart sank. Such a report had to be official. All 1 could do was to say that we had not had any such notification from the race authorities and as far as we were concerned, Firko was still an official runner.

As a result of this confrontation 1 had to tell Firko about the radio report. We still had not seen a race official and 1 was starting to feel a bit desparate. Firko’s brother Ron and his son Shane had arrived to cheer him home. As they needed to go into Melbourne to make some motel bookings and Rosanne needed to pick up our motel key, 1 suggested that they drive to Melbourne, track down Charlie Lynn and find out exactly what was going on.

Shortly after Firko’s second sleep we had our first good news. We had a visit from a couple of policeman who told us that they were there to estimate Firko’s speed so that they could estimate his final arrival time. They told us that Charlie Lynn had requested a police escort into Melbourne for Firko, something reserved usually for the leading runner only.

1 was quite amused when they figured that he would arrive at 8.30 pm. 1 told them that it would be closer to 3.00 am and that 1 had a week’s practise at this sort of thing. We eventually arrived at 3.25 am.

It was dusk when Rosanne, Ron and Shane returned from Melbourne. The news was good. Charlie had said to ignore the media reports. Firko would be an official finisher. He would get his medal and Finisher’s Certificate. They would keep the Finish faciIities open until Firko arrived, no matter what time that was. There would be hot food and cold beer waiting for us. The TV cameras would be there waiting and the Police escort would see him right to the finish.

Clearly Charlie was bending over backwards to undo the damage of the erroneous media report of Firko’s withdrawal and was honouring the arrangements that 1 had made with him.

It was a great relief to me and 1 could now concentrate on getting Firko through the final kilometres to the finish.

We had become quite a cavalcade as we wound our way through the outskirts of Melbourne. Two Police cars with flashing blue lights up ahead, then Firko followed by the first van with its flashing amber lights, then Ron’s car, the second van and finally the night security ute with its flashing amber light and huge sign “Runner Ahead” on its rear.

1 was still very concerned about Firko’s condition as I knew that he had already exceeded his limits of endurance, but he kept putting one foot in front of the other. My greatest fear was to have him collapse with only a few kilometres to go. 1 seemed to be the only one so concerned. The rest of the crew, other than the drivers, had donned their shirts with “Firko’s Crew” emblazoned on the front and were walking in a group around Firko. 1 remained steadfastly at his right shoulder.

Suddenly Firko veered off to the left and ran off the road. “What the hell is going on?” 1 wondered as 1 chased after him. 1 caught up with him in front of a flower seller’s stand that he had spied.

“Alf, can you lend me $5 to buy Barbara some flowers?’

1 can’t think of another runner who might have done anything similar, but then Firko is one of Nature’s gentlemen. He might even repay the $5 sometime.

With ten kilometres to go we were joined by Charlie Lynn who walked to the finish with Firko. I thought that this was a very touching gesture as Charlie had had virtually no sleep during the past 48 hours and this was beyond the call of duty. But then Charlie is also a Sydney Strider.

The final few kilometres seemed an eternity, as they always do, no matter how long the race. After eight days and sixteen hours they seemed to stretch on forever.

Finally there was the Westfield Doncaster shopping centre. The final 50 metres straight to the tape. The bright arclights to enable the TV cameras to catch the moment. Firko kissing Barbara. Firko hugging his mother, who had made a special journey to Melbourne to witness the finish. Handshakes. Backslaps. Pandemonium.

Charlie hanging the most enormous gold medal around Firko’s neck. Ken dashing hither and thither with his video camera.

Suddenly we were inside a warm tent. Charlie had honoured his promise. There was warm pizza and cold beer.

1 was all choked up. It was a combination of tiredness, release from the emotional pressure of continually monitoring Firko’s condition and the sheer ecstasy of the moment. I could feel the tears welling up. All 1 could do was to pat Firko on the back as I pulled the tag on a can of beer.

The joy was that Firko had conquered his own personal Everest and 1 was proud to be a part of his team, a team which had supported him to the hilt, to the extreme limits of their own endurance. 1 am sure that they will all join me in saying: “It was a magnificent effort, Firko, and it was a privilege for us to witness it. We are really proud of you.”

As 1 sat there sipping my beer the words from the Burl Ives tape kept ringing through my head.

“And the joy we share as we tarry there, “None other has ever known; “Come home, come home, its suppertime; “The shadows deepen fast, “We are going home at last.”