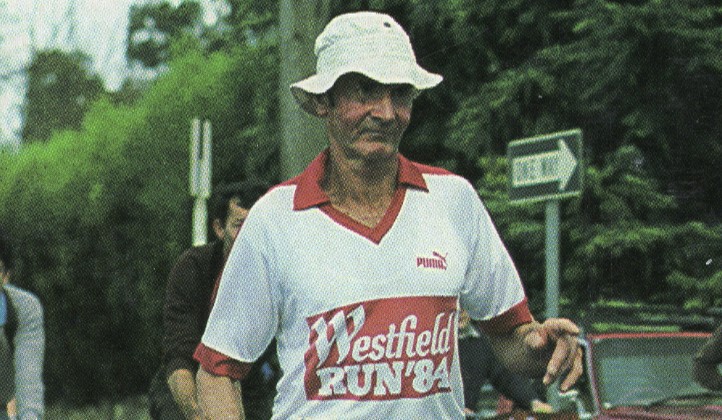

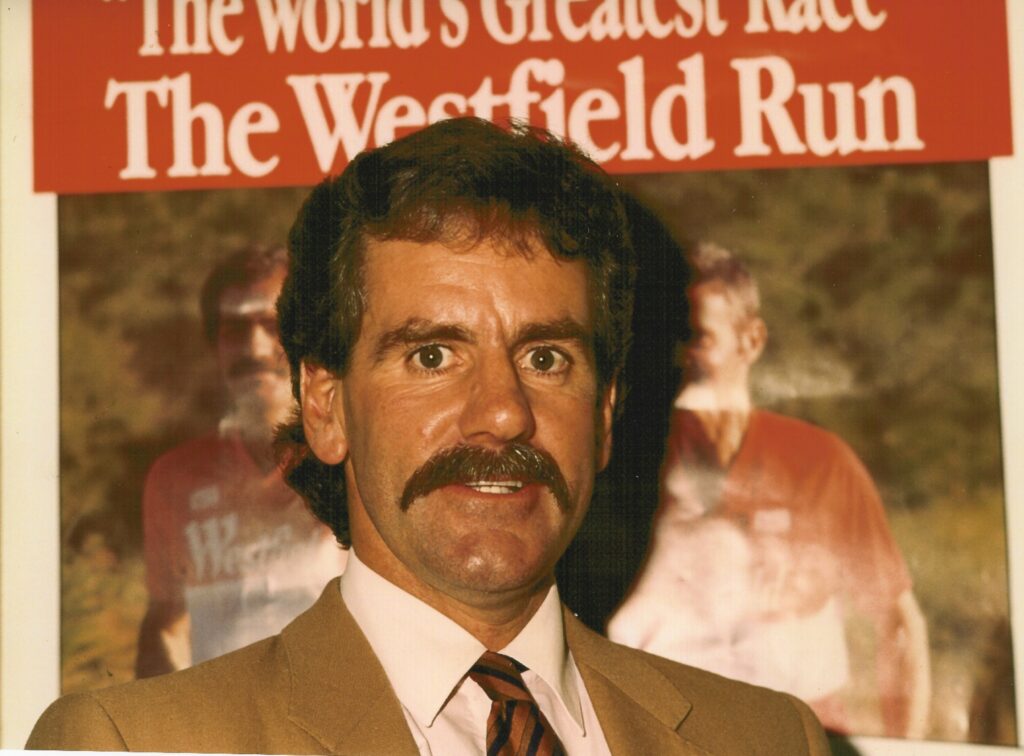

Vx117450 Private Albert Ernest Clifford `Cliff` Young was a potato farmer and athlete. He lived at the family home in Beech Forest with his mother, Mary, and brother Sid. Cliff spent just over 2 years as a Sapper in the Royal Australian Engineers during WW2 from 28 August 1942 to 3 January 1945. Cliff is best noted for his unexpected Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Ultra Marathon win (875 kilometres), in 1983 at 61 years of age.

Cliff trained for the race by running in gumboots on his property and is renowned for his ungainly running style. He ran at a slow loping pace and trailed the leaders for most of the course, but by denying himself sleep and running while the others slept, he slowly gained on them and eventually won by a large margin. He was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) “for long distance running”. A memorial in the shape of a gumboot in Beech Forest is dedicated to him.

This is the background to a remarkable story that won the hearts of a nation.

Click here to see how a 61-year old potato farmer beat the best ultramarathon champions in Australia

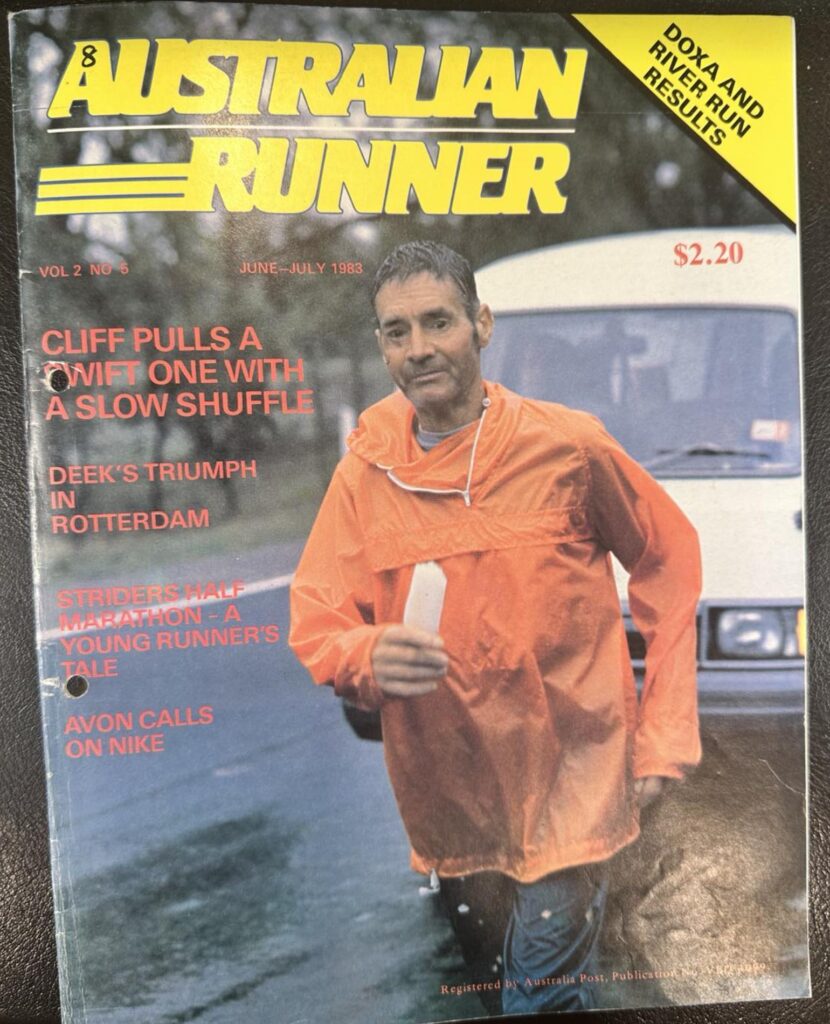

The following article published by Les Johnson in the June-July 1983 edition of Australian Runner magazine tells the story of the almost accidental origin of what was to become the World’s longest, toughest, and richest ultramarathon; the inner machinations of a crew supporting a long-distance runner; and the emergence of a most unlikely hero.

Cliff pulls a swift one with a slow shuffle

The Westfield Shoppingtowns Marathon ’83 grew out of the longstanding rivalry between Australia’s two best known ultra-marathoners.

Tony Rafferty and George Perdon had chased each other’s “records” for years but not each other, for they had never met. They were always ready to engage in verbal skirmishing, however. Generally, the tacit urn Perdon, who has run a sub-2:20 marathon, “won” the performance battle but lost the verbal war to the more articulate and personable Rafferty.

John Toleman, managing director of a sporting retail group and himself a former top professional runner (he held the world professional two-mile record at 9:05.0), is Perdon’s employer and manager. Toleman came up with the idea of a $10,000 winner-take-all challenge between the two down the Hume Highway connecting Sydney and Melbourne. When the logistics of such an event proved beyond him, Westfield stepped in with sponsorship and threw the race open to all-comers.

Which is how we came to be in the Centre Court of the Westfield Parramatta Shoppingtown at 10 am. on Wednesday, 27 April, waiting for a seemingly interminable round of speeches to end and a seemingly interminable race to begin.

We – myself, Brian Lenton, Bill Connellan and, from the weekend on, Chris Wardlaw – were there to manage John Connellan in the Sydney-Melbourne. The idea that John should enter had come during our period of altitude training at Falls Creek over the summer. It more than once gave us pause to reflect on the rarefied air’s effect on the supply of oxygen to the brain!

‘Blue’, as John is known to most of us, was not very fit when he arrived at Falls after Christmas. He had been running about 30-40 kilometres a week since November, hardly having run throughout most of the year. ‘Epics’, long runs through the Alpine areas, have become a feature of recent stays at Falls. One from the foot of Mt Bogong to Falls, another from Falls to Mt Hotham and back; none was planned for this year, as the selection trial for the World Cross Country was imminent. As one of the few to have done all the preceding “epics”, John wanted to continue the tradition. He did, with a run from Falls via the Niggerheads and Mt Fainter to Bogong Village, and then back up the Spion Kopje spur to the summit and on to Falls. It seemed natural to look at Sydney-Melbourne after that. Besides, John had always nurtured a secret desire to do Sydney-Melbourne, having trained seriously for the coast race some years previously.

‘Blue’s’ training picked up. From 40 to 110 kilometres a week, then up to 130-15O by the time he left Falls. Respectable, but still not enough to condition the legs for an 875-kilometre pounding on the highway from Sydney to Melbourne.

Chris Wardlaw, ostensibly manager of the venture but, in reality, somewhat closer to having an advisory role, devised a training schedule. Twice John should do three consecutive days of 80 kilometres; in March, the Frankston-Portsea race followed by a run home for a total of 11 S kilometres and followed again the next day by a 40 kilometre run at Ferny; another 65 kilometre run at Ferny – all the time building endurance into his legs.

After a preliminary discussion with Chris and John, Brian Lenton and I sat down together in early April to work out a race schedule. We set a target of 120 kilometres a day which would bring us into Melbourne well under the record of seven days nine and three quarter hours held by New Zealander John Hughes.

Two important advantages we had, so we reasoned, were that we would be able to stop at motels along the way, thus ensuring John of adequate – and restful – sleep; and, that we would, theoretically, be able to push through the last night into Melbourne, thus putting a final time of under seven days well within John’s reach.

It all looked too easy. A good distance runner, and Blue had been an All-Schools cross-country champion and, despite numerous periods of less than peak fitness, had still managed three sub-2:40 marathons and A-grade steeples for Glenhuntly since then, could beat the ultra-men by running a normal day at a good pace and getting a normal night’s sleep in a comfortable bed. Things didn’t quite turn out that way, either for us or for the other experienced ultra runners, as this account, reconstructed from my race journal, makes all too clear.

At around 4 p.m. on Saturday, 30 April, John Connellan’s part in the Sydney-Melbourne race ended at the Tumblong pub, some 373 kilometres and just over three days into the race. John’s feet were swollen and he had blisters on his big toes which looked slightly infected and ran the risk of becoming something worse. Although still on schedule and feeling as good as any one who has run that distance in three days can, John and his crew decided that common sense should prevail.

The race had started at 10: 35 a.m. the previous Wednesday from the Centre Court of the Westfield Parramatta Shoppingtown. “Blue” had started as he finished – walking – but then it had been a planned response to any surge of adrenaline.

Others had ridden the adrenaline surge. John Hughes, the New Zealand older of the Sydney-Melbourne record or one. As the opening speeches had dragged on, Hughes, visibly hyped up for the start, had wandered around the Centre Court like a caged lion. Predictably, he had then gone off like a rocket, covering the, first mile in around six minutes.

Hughes had been aided and abetted in that pace by Wal McCrorie. Together they covered the first 10k in 36 minutes – a pb for McCrorie. Bill Luke, McCrorie’s road manager, explained to us later during a roadside chat: “I told Wal just to go out and burn off his adrenaline at the start.” As their race strategy was to run-walk the distance anyway, it would make little difference. Not to them perhaps., but it may have to Hughes. Of all the pre-race speeches, perhaps the only one of any relevance was Robert de Castella’s, though he began with the strange in the circumstances admission that he felt “unqualified” to address the runners.

“You will be competing against three things,” Deek said, “against yourself first, then the distance and, finally, your competitors.”

After that hectic first 10k, McCrorie had assumedly burnt off all his adrenaline as he stopped for a walk. Behind the tearaways, the rest of the field, with’ the exception of Tony Rafferty, had been sucked along. Martin Thompson was dogging George Perdon’s every step, but if it was worrying George, he didn’t let on.

Blue had stuck to his pre-race plan and walked off the line, but he was still running at seven-minute mile pace for the first 80 minutes. Brian, Bill 1and I were hoping that musical director Frank Jordan had included some down-tempo numbers on the first tape in the series for the Walkman player that John was intending to wear for most of the race. We didn’t want him slowed down by ‘The Wall’.

Lunchtime came and went. A couple of sandwiches and a cup of tea taken on the walk. Getting John to eat anything solid during the day was to become one of our – and, I assume, his – problems for the rest of the race.

Dr Dick Telford, head sports scientist at the Australian Institute of Sport, had recommended a daily intake of 11,000 calories, about four times the requirements of the average marathoner training at 160 kilometres a week! With Blue, this obviously wasn’t going to come in food, as he ate sparingly, if at all, on the road, and only as much as his crew off it. The saving factor was his intake of about six litre of a 10 per cent Polycose solution per day. This worked out at about 6000 calories. It also created stomach problems, resulting in ever-increasing requests for toilet paper and, subsequently, vaseline.

Still, these worries were not to become evident on the first day’s run to Mitta gong. Despite slowing a little over the last 10k, Blue ran into Mittagong right on schedule. We finished at 6:50 p.m. with 93 kilometres covered and checked into our motel.

Our reception from Peter and Judy at the Mittagong Motel made us even more certain that staying in comfortable surroundings would be our trump card. A three-course meal washed down with a couple of beers, and Peter even promised to get up and make breakfast for us at 5 a.m. to make our start an hour later a little easier. Blue had his massage and went to bed well satisfied with his first day’s running.

While we slept (and dreamt of having more), our race strategy, and everyone else’s, was being demolished by a 61-year old potato farmer from Beech Forest in Victoria’s Otway Ranges. No one else stayed in such luxurious quarters as we did, but they all did stop on that first night. Cliff, and his teammate Joe Record, just sailed right on. By the end of day one of the race (the race day was based on a 24-hour period from the start, so ended at 10:35 a.m.), we were 10km ahead of schedule, having covered 130 kilometres. Cliff had completed over 180!

Others more knowledgeable than us said that he didn’t know what he was doing. He couldn’t keep it up. Who were we to argue?

Apart from nagging doubts, day two brought constipation for the road crew and the first onset of the diametrically opposite problem for Blue. It gave me the chance to make the day’s acutest observation: “Constipation is wanting to go to the toilet all day long – except when you are actually there.”

It brought, too, the first samples of John’s on-the-road humour. Martin Thompson, the one who had gone closest to matching the pace of Young and Record, pulled out. The following exchange took place:

Crew (encouragingly): ‘Martin Thompson’s just gone past in a car’.

Blue: ‘Well, flag him down. I want a lift’.

Day two again saw the 120 kilometres achieved relatively easily. We finished at Cullerin, some sixteen kilometres short of our stop at Gunning. We drove in. Perdon and Hughes, who had been just ahead of us, gutsed it out. A 16-kilometre loss on them to make up. As for Cliff, forget it! He just kept on going through every place.

The other demoralising factor which was starting to build up was our inability to put the tailenders behind us for good. Every day we would pass Bruner, McCrorie and Rafferty (Swift was out). Every night, while we slept, they would push past us again. They just wouldn’t stick to our rules!

This wouldn’t have been such a factor if we had been keeping in touch with Cliff. But we weren’t. At least we had the partial excuse that our ignorance of ultras had caused us to misjudge Young’s capabilities. How must Perdon and the others who had assumed Cliff would fall in a hole have felt?

As far as information went, we adopted a modified version of the mushroom theory. As long as all the information on the race came through us, we reasoned, it would be possible to present it in a favourable light. In practice, we wouldn’t tell John that Cliff Young was 50 kilometres up, unless we could add, “But he has just been run over by a bus!”

But John wanted the information. So this became a source of tension, considerable at times, particularly on the Saturday, as his physical condition gave out.

In all, a fairly healthy relationship was forged between Blue and us. We knew, more or less, what were the minimum demands of runner and crew, and were able to operate amiably the whole way.

The race strategy, unfortunately, was unfortunately not standing up to the pressure so well.

The appearance of the Transmedia film crew was always a welcome sight for the “real” crew. It always seemed to give him an observable boost and, at the same time, take the pressure off us.

On no occasion was this more evident than on the Friday as we went through Yass. The whole psychological mood of that day was down, from the time that we had to drive back from our motel at Gunning to Cullerin, right up until mid-morning. Blue seemed to be making more demands than ever of the crew, so much so that we began to feel guilty about even stopping for a roadside “cuppa”.

The appearance of Deek and Gayelene Clews on a visit from Canberra and some local media coverage as we passed through Yass itself relieved some of the gloom, but when Blue stopped to have his feet massaged just outside the town, he looked in trouble. He started again with us looking on warily.

Shortly afterwards the film crew came back to do some footage, using a motor cycle with sidecar to film John on the road. Buoyed up by this (and the massage and crew?), Blue began running better than he had since the first day. In two hours running, he took 10 kilometres out of Tony Rafferty and five out of John Hughes. He was flying, and, as we were starting to find out, his moods were transmitted to us.

Later that night he was struggling again, and we abandoned the day seven kilometres short of our target – Jugiong. This attitude, we all now acknowledge, was one of our shortcomings. We just didn’t spend long enough on the road. Saturday dawned (well, pre-dawned) with our five o’clock alarm. Chris, who had joined us after school on Friday, opened his eyes fractionally, and. observed: “If we feel like this, how must he feel?“

This was, we all realised, building up as the crunch day. Blue didn’t seem anxious to get on the road, lingering over his toast and massage while we waited impatiently in the rain. Once on the road, though, his attitude was really positive. Mentally, he was breaking the distance down into five kilometre sections which he aimed to complete in 30 minutes.

He reached Jugiong and sailed up the steep hills leading out of the town. Most of the other runners in the race had walked these – though we didn’t really need any further convincing that Blue was the best runner in the race. (It was becoming increasingly evident that the race would be won not by the best runner, but by the best endurance athlete).

Blue was now starting to struggle and the crisis to approach. Our plan was to convince him to push through to the Tumblong hotel, nine kilometres past Gundagai, where we had organised a shower, a meal, and a massage by Jock Plunkett, our masseur. With this as bait, we all counted down the distance to first Gundagai, and then Tumblong.

We had been counting on Saturday as a good day. People would be driving up from Melbourne on the weekend and this would be a boost to John’s morale.

The first arrival, Mike, an old friend, did not quite have the desired effect. With Blue’s positive mental approach, we were more determined than ever to prevent him worrying about where the others were. By our reckoning, we should start to haul them in over the next few days anyway.

Mike met Blue on the Gundagai bypass. He stopped his van and jumped out to take a photograph. Watching from our van, Brian and I assumed he was a local newspaperman. While we were sitting there thinking that a bit more media would be a boost for Blue, Mike was unwittingly helping the process of demoralisation along by divulging the full race position to Blue. It was not encouraging – Cliff and Joe Record out of sight, even Rafferty still a good few kilometres on. Not reassuring for a man with severe chafing, blistered and swollen feet, and who was starting to have both physical and mental doubts.

It was round about then that we realised that we had calculated our distance from Tumblong incorrectly. We had been taking the distance to Gundagai as shown on the freeway markers, and adding on the nine kilometres to the pub. We had left out the five kilometres between the two Gundagai turnoffs. Telling Blue that he had five extra kilometres to his break was not easy. Yet, if we didn’t, he would soon figure it out for himself and lose confidence in us. I told him. The look on his face was, I imagine, something like the look that Muhammad Ali would see in an opponent whom he had just nailed. We confirmed the distance to go at nine kilometres. “Can you make it?“, we asked. “Yes,” came the reply.

All morning, we had been letting Blue get about 500 metres up the road after his drinks, driving past, then stopping another kilometre further on – an interval of 1500 metres. Blue, on the other hand, thought we had been giving him one kilo metre start – a break of two kilometres.

So, he fixed his concentration on four more efforts, then the Tumblong pub would be in sight. Four more drink breaks though, left it still tucked around a bend in the highway. As far as Blue was concerned, the Tumblong hotel was a pub on wheels!

Just as Blue had based his estimate of the distance to Tumblong on the interval, between drinks, so we had relied on the RACV map in our race logbook. Both were wrong. The distance shown as nine kilometres was, in fact, eleven. Both runner and crew were wondering just where in hell this pub was. The difference was, neither the crew nor the van had to torture themselves to get there!

By both our calculations then, the pub should have been in sight. It wasn’t; though as we waited for Blue to struggle up to us for his drink, Tony Rafferty was. Three things happened coincidentally, and the combination was disastrous. Blue reached us for his drink. Rafferty disappeared behind the only trees still standing on the last bend before Tumblong. And the hapless but innocent Mike reappeared on the scene returning, as (ill) luck had it, from Tumblong. So, there was Blue, shattered. Convinced that his crew were, and had been for a while, lying to him about the distance, were now lying to him about Rafferty, and that the Tumblong pub probably didn’t exist!

He rounded on Mike. “How bloody far is it too Tumblong? ,” he demanded. At the answer, “seven kilometres”, he sat down on the side of the road and said: “Put the marker down and drive and drive me in.”

Worse, if possible, was to come. Our masseur Jock, worried about Blue’s whereabouts, and hearing one report that he was limping along the road, had left the pub to drive back and see if he could help. Unbeknown to us, he passed us while we were all in the van, and continued up the road as far as Coolac.

Ultimately, it probably made no difference. But it was a body blow to all of us when we finally reached the pub. Shattered was probably too mild a word. We searched for Jock along the road and in Gundagai, but to no avail. By the time he turned up, Blue had more or less convinced himself to withdraw. He was tired, his feet badly blistered and swollen, and our race strategy was in tatters. Gutsing it out is a fine-sounding concept, but it seemed to have limited applicability to a situation in which you are behind, getting further behind, and not quite half-way into an 875- kilometre race!

Jock ultimately returned and Blue did make an attempt to restart. But it was, I feel, more to convince us that he could not carry on than to convince himself. The end came at the Tumblong Hotel. Blue walked a few metres past it. At least we could say that we had passed it once!

Our attempt to convince Blue that Tony Rafferty had been just ahead of him that morning was still fresh in Brian’s and my minds as we drove from Tumblong to Holbrook late that afternoon. Four days previously, it would have been galling to think that such men would beat us. We were all coming home with an increased admiration for the persistence and endurance that enabled them to do just that.

Finally, what can you say about the winner, Cliff Young? He made us all look like mugs – the blissfully ignorant, like us, and the experienced and talented runner/endurance men like Perdon, Hughes and Bauer.

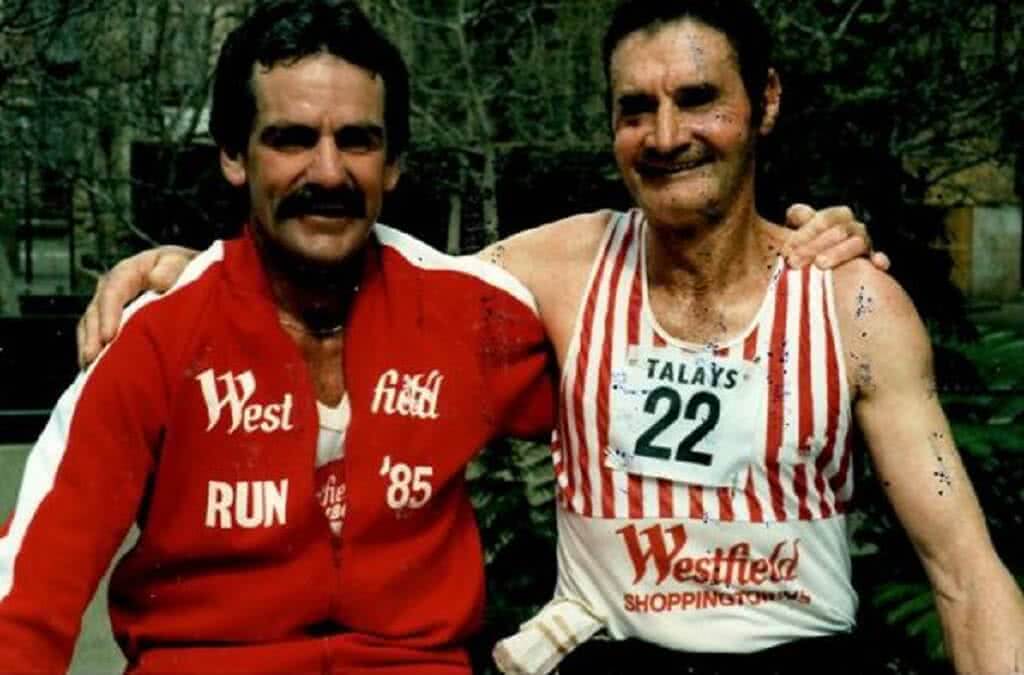

He did it by exploiting the conditions of the race to the full. No rests for Cliff. He stayed on the road longer than anyone else – with the possible exception of Rafferty – and, on the rare occasions when he was challenged, clung to the lead with a stubborn tenacity. Only Joe Record mounted any sort of challenge, staying closest to Young, and actually heading him for a brief period on Saturday night just near Albury. The story told – which should be true if it isn’t – was that, on catching Cliffy, Joe put his head inside his caravan and said, “Yoo-hoo Cliff, I’m here.“

Before he had got 400 metres up the road, Cliff was up .and chasing.

Actually, I think that Joe was the second-best runner in the race, for the simple reason that he was the only one who gave himself any chance to win it. Sure, he didn’t finish, but at least he was in a winning position for most of the way. The others were all running for second place once they had made their fatal misjudgement that Cliffy couldn’t keep going.

Perdon, Hughes and Bauer may have been in a position to mount a strong challenge over the last 24 hours, but all seemed to panic as Young approached the border. All three pushed on well into Saturday night, gained nothing, and lost their chance.

It just may have been possible to make up the 60 kilometres leeway on the last full day by making a supreme effort to run right through at a pace equivalent to two kilometres and a bit faster per hour than Young was running. In the event, the Saturday night effort left none of those three in a position to mount such an effort.

So, all hail to Cliff. By instinct or design, he took advantage of the way the race was run, established a lead, defended it tenaciously, and deservedly reaped the reward.

Click here to view ‘Cliff 1983‘ – an inspiring documentary by Neil Kearney

Epilogue:

That night we stayed at Holbrook. We were all a bit disappointed, but no one regarded John’s effort as a failure. We accepted his reasons – on looking at his feet, one could hardly do otherwise.

What had defeated us? Several reasons came to mind, but none was more important than the lack of two critical requirements – condition, and the ability to run slowly.

For Blue, running slowly meant nine-minute mile pace and, as he had observed, we tended to pull him off the road when he dropped down to that pace. An interesting statistic: while Cliff Young was on the road, he averaged just over seven kilometres per hour, John averaged nine.

But Cliff and the others had the ability to keep covering the ground. Run, jog, shuffle, then walk: it didn’t matter how, they would keep on going. And while we rested, they forged further ahead.

As mentioned earlier, this was most evident with Tony Rafferty. Had we been able to keep on going, Sunday morning probably would have been the last time we saw him in the race. But the fact that he was able to cover the same distance as us for each of the first four days solely through being prepared to stay on the road for almost 24 hours a day, forced us to question many of our assumptions about the race.

We all came away with a vastly different attitude towards the ultra-men. While I still wouldn’t put them on Deek’s level, theirs is a distinctly different sport from distance running. As Chris put it during one of our postmortems: “We train to run fast for an hour; they train to run all day.“

Cliff’s Winning Ways

‘I’d like to run a 100 mile before I die but I’d have to be fit for that one.’

Those were the words of Cliff Young after one of his first attempts at ultra-distance racing, the Victorian Marathon Club’s 50 miler at Melbourne University two years ago.

True to his nature Cliff wrote to race organiser, Bill Luke, thanking him for his work and also thanked the other runners in the race for their encouragement.

The rest of the note showed the humour and sincerity of the man who has shown to so many Australians that a strong will and perseverance can come through a winner.

The note went on to say: ‘I pulled up pretty good after the run, bit have a crook back and hip at present, they went when I tried to lift a sick cow – heavy things cows’.

‘I’d be glad to run in any runs you organize over any distance, though I’m not too rapt in sprints – too short and fast for me.‘

The success of Cliff Young and the publicity the run generated surpassed even Robert de Castella’s wins in the Brisbane Commonwealth Games and the Rotterdam marathons.

Major television networks devoted large parts of their news services to the run, with live crosses during programs to check on Cliff’s progress. The Melbourne Age, probably Australia’s most serious newspaper thought Cliff’s efforts were worthy of an editorial.

It is difficult to put Cliff’s performance in perspective. So few races of this type have been run in Australian that there is no accurate measuring stick. But looking at the others in the field it is clear that Cliff not only beat Australia’s endurance athletes but also ran away from runners with credible marathon times such as George Perdon, John Hughes and Martin Thompson.

If the race was run in stages then Cliff’s chances would be greatly reduced, but then it would be less a race of endurance and one better suited to the fast marathon runners.

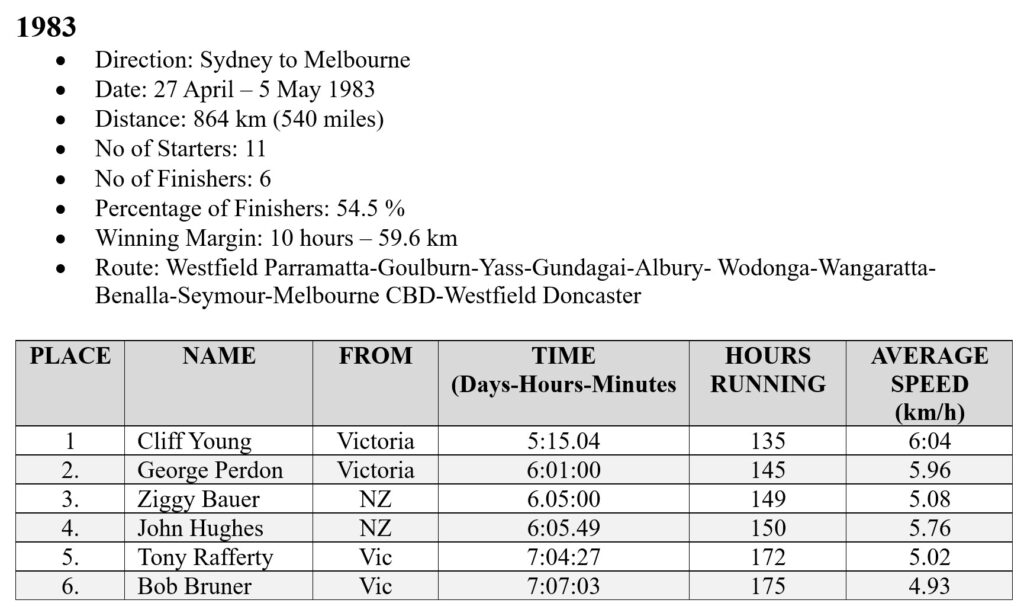

He not only re-wrote the record book with his time of 5 days, 15 hours,and 4 minutes, but also the tactics and way to run such an event.

Ten thousand people gathered to honour him in Melbourne’s City Square.

In Colac, the nearest large city to his own home town of Beech Forest, 15,000 people were there to congratulate him on his return.

Ultra distance racing will probably boom in Australia now. Overseas runners will arrive to take on our best, the Sydney to Melbourne run will become the classic of the sport. The time taken to run the 875 kilometres will be whittled down under five days. Many of the runners who took part in this first Sydney to Melbourne will be forgotten.

But one thing will not be forgotten. And that’s the performance of Cliff Young. Like Phar Lap, Don Bradman, and other great Australian sporting legends, his performance will only be seen to be even more meritorious as the years part.

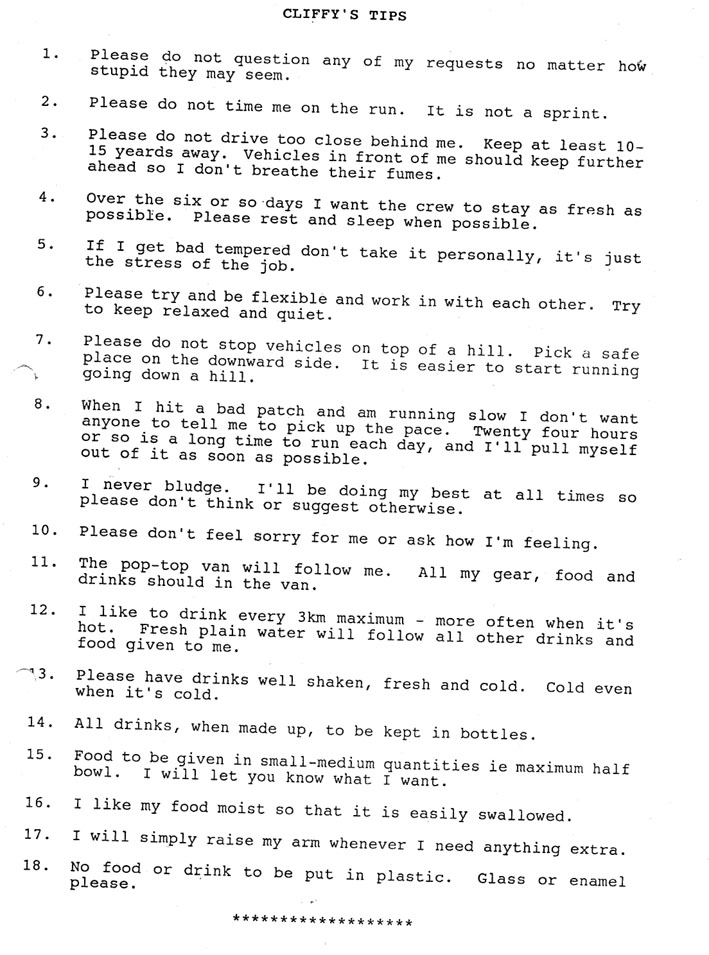

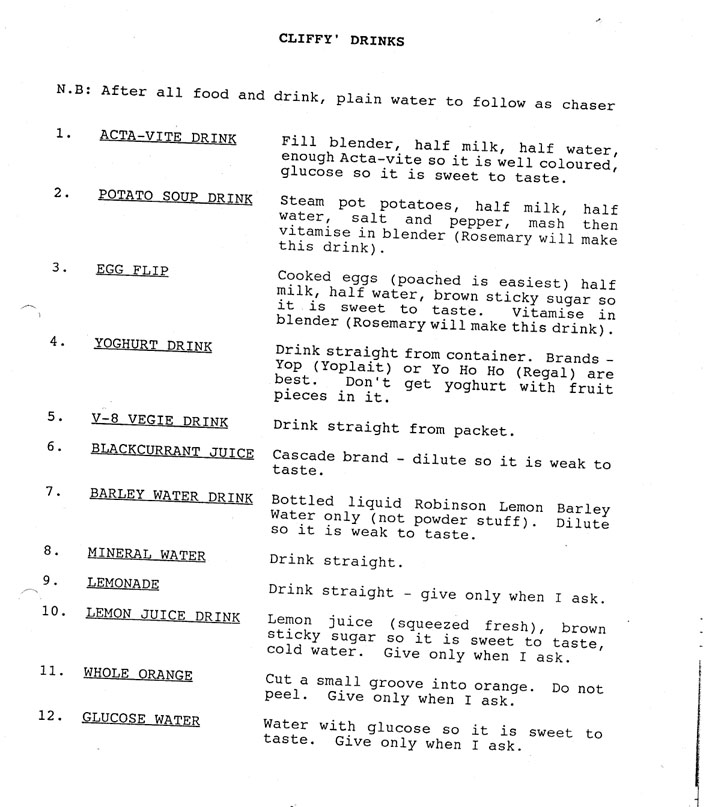

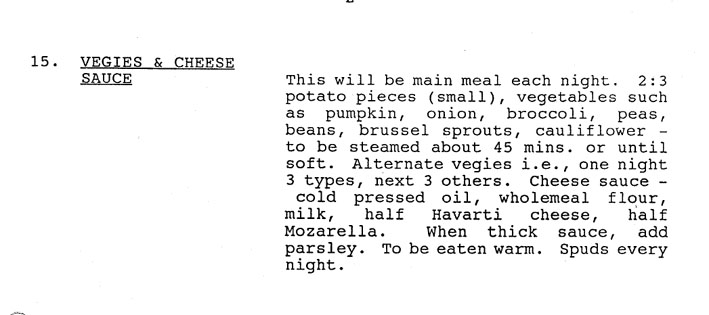

CLIFF’S GUIDE FOR HIS SUPPORT CREW

LINKS:

- BEYOND ENDURANCE: The 1988 Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Ultramarathon – A Tale of Two Legends

- FIRKO’S RUN: An Epic Event

- ‘On the Run’ with Mountain Man

POSTSCRIPT

In April 1983 I was a major on the headquarters of the 1st Brigade at Holsworthy. The morning after the race started there was some lighthearted discussion over a 61-year-old potato farmer leading a field of younger ultramarathon runners through Mittagong. Many of us were involved in the ‘fun-running boom’ and I was in the process of organising an Anzac Day Marathon in Sydney. Over the following few days, it seemed everybody knew of the name ‘Cliff Young’ as television crews from all the major networks scrambled to cover the race. When interviewed at the NSW-Victorian border Cliffie announced that he would now run straight through to the finish at Westfield Doncaster without taking a break – and he did just that to win the race. When presented with the winner’s cheque of $10,000 he said he didn’t run for the money and donated $2000 to each of the other runners still out on the road still ‘doing it tough’. He became a national hero overnight.

I was not to know that I would soon receive a call from the editor of ‘Fun Runner Magazine’, Mike Agostini, to say he had been approached by Westfield to organise future events. He asked if would join his as the Race Director for the event. I accepted and went on to run the event, which was destined to become the World’s longest, toughest, and richest ultramarathon from 1984 – 1991.