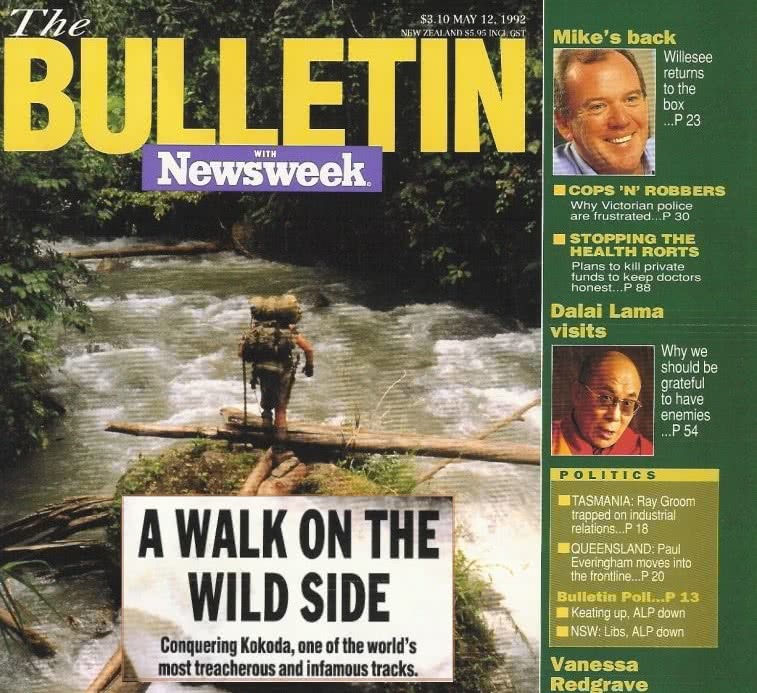

Leeches. Malaria. Blisters. Tinea. Treacherous creek crossings on narrow logs in the dark … writer Helen Pitt and photographer Valerie Martin (both 163cm and 59kg), with 18 other Australians, retrace the Kokoda Track nearly 50 years after the World War 11 battles.

IT IS bloody hard. That is why it is called the ‘bloody track”. In World War 11, you were regarded as a bloody hero if you crossed the Kokoda Track. Now, if you do it by choice, you are seen as a bloody fool.

It is tough. Look at a cross-section of the Track and you will understand why swearing is the only way to describe the trek involved. You cannot judge the Track by distance (less than 100 kilometres); that fails to take into account its harshness. The highest point is 2000 metres, as high as Mt Kosciusko. Imagine climbing the stairs of the tallest skyscraper, then coming down a muddy embankment in the rain and fording a raging white-water stream. Do that for seven days on end, sometimes nine hours a day. Then you get a hint of what it is like.

Six women and 14 men paid RSL Travel $3000 each for the privilege. Accompanied by 22 villagers (cooks, guides, carriers), they conquered the track in the first trek to commemorate the 50th anniversary in November of the Kokoda battles of World War 11. Only a few Australian women had gone this way before.

We were from all walks of life and paths were unlikely to have crossed were it not for the Kokoda Track. Among us were a nurse, a Higher School Certificate student, a 54-year old grandmother, a 53 year-old plumber, a solicitor, a barrister, a sawmiller, an insurance salesman, a psychology student and a carpenter called Sean Wood. We met before the expedition to size each other up and compare levels of fitness. A muscle-bound state champion gymnast sat in one corner, and iron-man competitor in another.

Harry, father of seven and a sales tax consultant, caught my worried glance. “I’m sticking with you, kid,” he said. Not that I was terribly unfit. I was worried about my stamina. Others were, too. And that I was a woman. Papua New Guinea is dangerous for women, we were told. Over and over again.

Macho: As we gathered the list of recommended equipment, it became obvious that a man had put it together. Machete? Check. Ten litres of mosquito repellent? Check. Hobnailed boots? Check. Swiss army knife? Check. Two pairs of y-fronts! Hang on fellas – that’s stretching personal hygiene limits a bit.

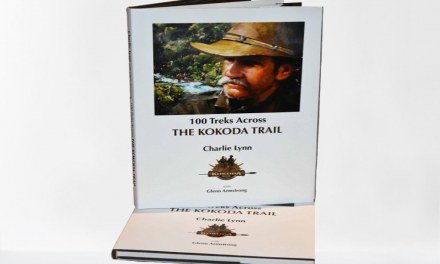

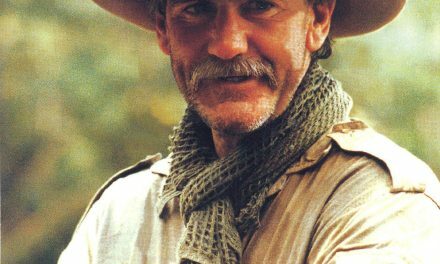

Charlie Lynn, the organiser, admitted later that the list was made for men: “We weren’t going to ask women along but we go desperate.” Lynn had appealed to corporations and local councils throughout Australia to send representatives but only one responded: Universal Press, publisher of street directories. At least we would be right for directions.

Lynn assured us that we would be only as fast as our slowest link. And if anyone could inspire confidence and perform miracles of motivation, it was Lynn. The retired major who devised the Sydney to Melbourne ultra-marathon convinced us all that we could handle the trials of the Track, despite the reservations of friends, family and colleagues.

This was the first of his monthly treks on one of the toughest walking track in the world. But “mental toughness, that’s all you require,” he assured us. Lynn said he wanted 20 ordinary Australians to do something extraordinary.

Each had different motivations. Six had fathers who had fought in PNG in World War 11. Some were trying to reach out to dead dads they had never known. One woman described the journey as like “washing a jumper with a piece of tissue. I find I’m always picking off bits of Dad.”

Some were reliving army cadet days. Others were putting ghosts to rest. Our nurse had been sent by her husband to “get the thing out of her system”. She had been studying the history of the Track for more than a year, had corresponded with a veteran and was a mine of information on the field hospitals and general war history of the Track.

So, packs bulging with salt containers to ward off leeches and heads loaded with horror stories from Kokoda veterans, we flew from Port Moresby. The flight turned out to be one of the most hair-raising segments of the trip. An identical Talair light aircraft had crashed, killing 11 people, the previous day and the sight of the rugged terrain of the Owen Stanley Ranges below was enough to turn knuckles white.

At the small town of Kokoda, people came from everywhere to the makeshift airstrip to welcome us. The battle of Kokoda Ridge was one of the most decisive in the Japanese-Australian conflict. It, and Isurava, Brigade Hill and Imita Ridge, were meaningless names of battles until we walked the Track ourselves and appreciated the difficult conditions that more than 6000 young Australian soldiers were forced to overcome in 1942. They were outnumbered six to one by Japanese troops.

We knew it would be hard even without an enemy.

Keeping the red shorts, white shirts and fluorescent green caps of the carriers in sight, we took one last look at our clean feet and left town for an each walk through a downpour to the first camp site. Locals shielded their children from the rain with banana leaves as they stood beside the Track to greet us. And don’t let anyone tell you it’s a trail. At times, calling it a track is being generous.

We dried our clothes overnight in the Seventh Day Adventist bush church and prayed we would get them out before the Good Friday church service.

Day1: The state gymnast notes in his diary just an hour into the trek: “Bloody hard hike so far. Never again.” Ninety minutes into the climb, Rod, the manager of an electrical construction company, decides he won’t make it. The first link in the chain is broken. Exhausted and extremely disappointed, he turns back to Kokoda to be flown to another village a few days walk down the Track.

A guide, Osborne Bogajiwai, leaves Kokoda Ridge 36 hours after us but catches up on the second day. he holds the record for having run the Track in 28 hours. Little wonder locals laugh when we say we are going to take seven days.

Lunchtime, and the race is on to get the packet of smoked mussels rather than the tinned sardines. We also have abundant rations of high-energy food: chocolate, peanuts, biscuits, cordial.

Then the rain starts again; pretty much the weather pattern for the entire trek. The scenery is superb. The smell of rainforest rot lingers along with the mist in each valley. White trumpet flowers dangle from the rainforest canopy and mounds of variegated purple leaves dot the narrow path. A blue butterfly piggybacks on the cap of a trekker for at least half an hour. We pass buttress roots covered in moss and fine tropical rainforest timber – a sawmillers dream.

Day 2: Evidence of former conflict. We see unexploded hand grenades, old mortar shells, bullets and plane wrecks. We ford many white-water streams on makeshift bridges made of logs held together with liana vines. One is put together in half an hour by our guides early in the morning. Socks off for better grip.

We are cold and tired and the rain has been constant. Smoked mussels again for lunch, sore muscles again at dinner. We are still wearing the clothes we set off in and the potpourri of smells around the campfire at night is definitely getting worse. It is the third night of wet tents and wet sleeping bags.

From here on, no one gets to the stage of saying “I can’t do this.” But there are times when we ask each other, “Why are we here?” This is one of those nights.

Day 3: The best part of the trip. Flat land – but deceiving. what seems to be an easy half-hour walk is two hours of exhausting mudflats. The only sound is mud squelching underfoot. Black, smelly mud. but it is worthwhile because that night we stay at Myola guest house, honorarily titled “the Hilton of the Track”. A bed. A hot shower from a bucket of water. Freshly cooked bread. The malaria tablets are washed down by sweet-potato soup. We sit at a table lit by a hurricane lamp and there is laughter and good spirits all round.

The only sound is mud squelching underfoot. Black, smelly mud. but it is worthwhile because that night we stay at Myola guest house, honorarily titled “the Hilton of the Track”. A bed. A hot shower from a bucket of water. Freshly cooked bread. The malaria tablets are washed down by sweet-potato soup. We sit at a table lit by a hurricane lamp and there is laughter and good spirits all round.

Day 4: The simple joys of life, such as dry socks, take on a new meaning on the Kokoda Track. We have been saving up for this treat because, however cautiously you try to avoid water, it is almost impossible to walk for an hour without getting your socks wet. Wet socks mean blisters and an increased likelihood of tinea, fungal foot and leeches.

The dynamics of our party have emerged. There are three definite groups. Some want to turn the trek into an iron-man test of wills. Others are more content with a stroll and a chat. A centre group drifts between the two. Photographer Valerie Martin and I gain ourselves the nicknames Valium and Memsahib as part of the straggler’s group.

We pass through many villages today. A welcoming party of surviving “fuzzy-wuzzy angels” – the nickname for the wartime native bearers – greets us with mandarins, sugar cane and taro. Makes a nice change from smoked mussels.

We slither down slopes in the rain and the tail-enders trek for a while in the dark. We trundle down a hill, following the flame of a hurricane lamp and those fluorescent green caps. The adrenaline flows. A single-log crossing over angry water requires trapeze-like concentration during the day but at night, wet and tired, we inch our way across as if every move is our last. We stagger up a steep hill and into bed. It is the most physically challenging part of the trip and the latest night: up well past our 8.30 bedtime.

Day 5: Reveille is always 04.30 hours; we hit the Track by 6.30. For those of us who are not morning people, the early morning “Coo-ee” is hell. All cheery people and snorers from the night before are severely chastised.

Simple things keep us going. a smile from a village child. An interesting chat with a fellow walker. A energy-boosting piece of chocolate to get you up the next hill. A laugh with a guide or an exchange with a World War 11 carrier. The occasional mantra (“I can do this”) – and a full water bottle.

With the smell of crushed ants, underfoot and the odd leech in the hair, we are led by the locals to one of the most moving and eerie sites on the Track: what they say is the graveyard of 72 Australians and one Japanese, marked out with sticks and red ribbons (see following story).

Day 6: Down, we vote unanimously, is worse than up. In the rain and mud, it is easy to slide out of control down any of the steep slopes; at least, going up, you can set your own pace. But going up this day is hard. Climbing Mt Bellamy, the highest point on the Track, is a test of wills. One veteran calls it a “mongrel guts” of a climb. There are 11 false peaks and 11 times you say to yourself, “Great, relax, it’s over,” only to be disappointed around the next corner.

At the top I scratch my name with my penknife into the makeshift visitors’ book, a clump of bamboo trees. Then it is down through tall kunai grass. It is hot, itchy and hard to see where the path leads. There are lots of falls. Get to the bottom and just jump in the creek to beat the heat. Spend an uncomfortable night at a makeshift camp site filled with bees, ants and marsh flies. Many have nightmares.

Day 7: Imita Ridge is uphill. It is hard to believe that Japanese troops, emaciated after weeks without food, struggled to the top. the Japanese entered New Guinea from the north in July 1942 and planned to take Port Moresby through Kokoda. but only three soldiers made it to Imita Ridge and they fired a shot in frustration when they saw the glow of lights from Port Moresby. So close, yet so far.

After every big “up” comes an equally tortuous “down”. Today, it is the overgrown Golden Staircase. We ford the waist-deep Goldie river for the last climb, the hill from hell. Our fitness level has increased but it is hot and almost straight up I keep telling myself I can do it and at 12.36 precisely I do. We reach the top, Owers Corner, with the biggest smiles on our faces. A handshake from a policeman and the local member of parliament greet us. Guide Neville Cleto, 22 leaves the group for a quiet cry. He says that everytime he finishes the Track safely, he feels closer to his dead grandfather who was a carrier in World War 11.

Lynn’s final words sum up how we all feel: “I’m sure there were times when it would have been easy to sit down, whistle up a helicopter and say, ‘Just get me out of here and out of my misery’. But you get to the top of a ridge, you recover a little, then somebody else arrives and you see they look pretty bad, worse than you. Then, together, you get to the next ridge. That’s how you get to the end of the Track.”

We might have reached the end of the Kokoda Track, but there’s another 40 kilometres to walk to the Bomana war cemetery – a mere stroll.

Anzac Day: As our group walks together to Bomana, mostly wearing the same clothes we had started out in, the crowd parts – probably because of the smell. The symmetrical rows of the thousands of white headstones of Australian soldiers are lit by the dawn. I stand in pyjamas (my only dry clothes) with a tear trickling as I catch the look on the face of a “fuzzy-wuzzy angel”. I glance back at our cook and notice he has the same expression.

Usually, Anzac Day services are too early in the morning for me to register any emotional response. But this one is different. We could not have walked the Track if it had not been for the locals. I understand why veterans called them angels giving “the love of a mother and the care of a nurse”.

We all leave the Track with new goals: one to learn to play the piano, one to climb Everest, one to do the trek again, this time in four days. Many have fungal food, tinea and blisters; one woman has malaria.

There are some remarkable personal achievements. Rod, who pulled out on day one, rejoins us for the last three days. Geoff, the plumber, would climb a ridge then turn back to record it on video.

Time heals all blisters and hindsight always makes a goal achieved seem much more simple. The bond between the 42 of us may dissipate but the bridges forged were not only of the log and liana vine variety. Stereotypes were broken down. We were just sweaty, smelly trekkers hoping to reach the next ridge.

At the end, I felt the world was my oyster – certainly not my smoked mussel. (I swear I will never eat one again.)

Helen Pitt